Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lily Guo and Version 1 by Mark Tefero Kivumbi.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a phenomenon where bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses that previously were responsive to medicines evolve to become less or unresponsive to these treatments, increasing the risk of disease spread, treatment failure, severe illness and sometimes death.

- antimicrobial resistance

- antimicrobial stewardship

- antimicrobial surveillance

- antimicrobial susceptibility

- resistance genes

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a phenomenon where bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses that previously were responsive to medicines evolve to become less or unresponsive to these treatments, increasing the risk of disease spread, treatment failure, severe illness and sometimes death [1,2][1][2]. The rapid evolution and spread of drug resistant microbes that acquire novel resistance mechanisms is a regular threat to our ability of treating simple infections like urinary tract infections and also more severe infections like bacteremia, tuberculosis and pneumonia that are life threatening [3,4][3][4]. There is also a rapid global spread of multi and pan-resistant microbes that are not responsive to most if not all available treatments [5]. Moreover, AMR can have a substantial economic burden, and also significantly affect national health systems, due to its effect on productivity of patients and/or their caretakers through prolonged stay in hospitals and the need for more expensive drugs as well as the need for intensive care treatment. Redundancy in prevention and inadequate treatment strategies against superbugs, and insufficient access to existing and new antimicrobials can result in high rates of treatment failure and even death in some scenarios, which will disproportionately impact those countries with more limited resources. Delicate medical procedures like surgery, cancer therapy, organ transplants and others, will become increasingly riskier and may result in death.

AMR is accelerated by clinical, biological, social, political, economic and environmental factors affecting both man, animals and the ecosystem [6]. The main drivers of AMR in developing countries, some of which also act as drivers in higher-income contexts, range from misuse and overuse of antimicrobials, self-medication, over prescription of antibiotics, high infection rates, use of antibiotics in livestock and fish farming, inadequate access to clean water facilities, sanitation and hygiene for man and animals, poor infection prevention and control strategies in the community, inadequate access to medical supplies like diagnostics, vaccines and effective drugs, ignorance, lack of medicine regulatory policies and poor enforcement of health regulation policies by relevant authorities [7[7][8][9][10],8,9,10], hunger and malnutrition, civil conflicts and poverty [7]. As drivers for AMR span both human and animal health, with strong environmental components as well, it is increasingly being viewed as a “One Health” issue, requiring multisectoral collaboration to establish effective surveillance and stewardship initiatives [11].

Uganda is a low-income country [12] situated in East Africa, and a member of the East African Community. Agriculture is a mainstay of the economy, with over 80% of the population estimated to engage in agricultural activities, although relatively little is intensive production. As a result of substantial health sector reforms initiated in the 1980s, more Ugandans now have access to basic healthcare services, including essential medicines, than ever before, although issues of quality and out of pocket expenses remain [13]. Antibiotics are widely available in local pharmacies, with rising concerns related to informal and unprescribed usage [14]. Over recent years, these factors have been suspected to be leading towards a growing trend of AMR and a decrease in positive treatment outcomes, with use of available medicines for both man and animal in Uganda [15]. In 2017, a World Health Organization-led Joint External Evaluation revealed weaknesses in Uganda’s efforts to address antimicrobial surveillance, highlighting that while detection of priority pathogens occurs, there is little coordination between sectors or operational guidance to support the country’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Action Plan [16], and also noted an absence of data on AMR activities within the veterinary sector [17]. The objective of this study was to determine the extent to which studies investigated AMR in Uganda, and to elicit information about trends in how these studies are undertaken that might help inform efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance in the country, including multisectoral coordination efforts, antimicrobial stewardship, policies and surveillance of resistance.

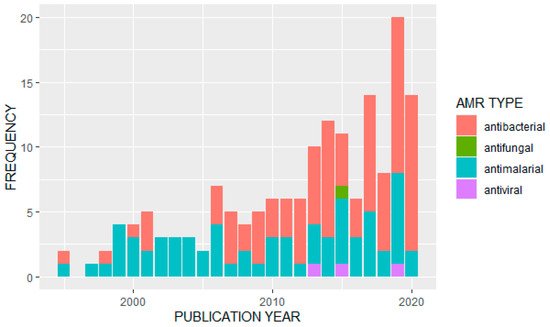

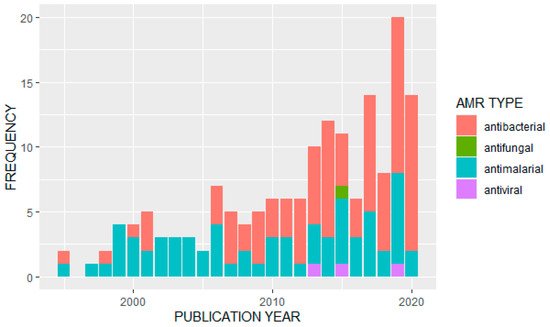

We observed an overall increase in the frequency of published studies on AMR in Uganda over time (Figure 32). Of the 163 articles analyzed, the majority (n = 91) reported data on antibacterials or antibiotics. Of these, the most frequently studied bacterial pathogens were Escherichia coli (n = 13) and Staphylococcus aureus (n = 11). A further eight studies looked at Salmonella species, Streptococcus pneumonia was also covered in eight studies, and seven studies were on tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Klebsiella pneumoniae had four studies while Enterococci species, H. influenza, V. cholera (cholera) and H. pylori were also covered by identified papers. Major antibiotics that were used for surveillance of antimicrobial resistance included: penicillin, tetracycline, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, sulfonamide, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, vancomycin, erythromycin, oxacillin, methicillin, clarithromycin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and other fluoroquinolones.

We observed an overall increase in the frequency of published studies on AMR in Uganda over time (Figure 32). Of the 163 articles analyzed, the majority (n = 91) reported data on antibacterials or antibiotics. Of these, the most frequently studied bacterial pathogens were Escherichia coli (n = 13) and Staphylococcus aureus (n = 11). A further eight studies looked at Salmonella species, Streptococcus pneumonia was also covered in eight studies, and seven studies were on tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Klebsiella pneumoniae had four studies while Enterococci species, H. influenza, V. cholera (cholera) and H. pylori were also covered by identified papers. Major antibiotics that were used for surveillance of antimicrobial resistance included: penicillin, tetracycline, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, sulfonamide, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, vancomycin, erythromycin, oxacillin, methicillin, clarithromycin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and other fluoroquinolones.

Of the other types of antimicrobials covered in the identified studies, 68 papers reported data on antimalarials. Twenty-one studies reported primarily on resistance to artemisinin derivatives and/or common components in artemisinin-based combination therapies; 18 studies reported on resistance to multiple drugs or drug classes, with common combinations including chloroquine and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine or looking for multiple resistance genotypes. Fifteen studies focused primarily on resistance to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine or other antifolates or sulfonamides, and thirteen studies focused on genotypes or phenotypes associated specifically with chloroquine resistance. One study did not look at a specific antimalarial treatment, but associated strain diversity with treatment failure. Only three studies were identified that reported on antiviral resistance, of which two focused on the hepatitis virus (one on hepatitis C, and the other in hepatitis B in patients co-infected with HIV and undergoing antiretroviral therapy), and one focused on resistance to antiretroviral treatment. We located only a single study that discussed antifungals, on Cryptococcus neoformans.

There was similarly a heavy emphasis on the human health sector in the studies we identified, with 145 studies (over 88%) reporting data from human subjects, 12 studies focused on animal subjects (five focused on cattle, five on chickens’ and two on pigs/swine), while only six identified studies used a One Health approach. Of these, four studies looked at animal workers and their animals (three of which were cattle, and one was chickens), and two looked at animals and humans in the same geographic locations; the first covered a broad variety of animal species (cattle, goats, pigs, sheep and non-human primates), while the second focused more narrowly on pigs and birds, but also included environmental sampling from ponds, animal waste and sewage. This was the only study we identified that included environmental surveillance. All the veterinary and One Health studies focused on bacterial pathogens and/or antibiotic resistance, with the most commonly targeted pathogens being E. coli and Salmonella spp., with five and six studies, respectively, focusing exclusively on that pathogen. One study looked both at E. coli and Salmonella (a study in dairy cattle), and five studies looked more broadly across different types of bacterial pathogens or antibiotic resistance genes and phenotypes. Overall, there was a strong food safety focus, with all but one of the veterinary and One Health studies focused on livestock and food-producing animals; only one study also considered wildlife (non-human primates in national parks adjacent to agricultural areas and human habitation). We observed that the veterinary and One Health studies were all relatively recently published, with the earliest dating from 2013, and the majority published in 2019 and 2020.

Overall, only ten of the studies were laboratory-based, whereas the remaining 153 studies were done in the field, with recruitment specifically taking place in clinical/hospital settings. None of the human-focused studies appeared to include surveillance or recruitment at the community level, although all the veterinary and One Health studies were conducted in communities. Eighty-three of the studies produced results on resistance genotypes (Table 1), while 80 studies focused on simply looking at resistance profiles of the microbes, for example, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus, riphampicin-resistant tuberculosis, vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, beta lactamase-resistant E. coli and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. None of the articles we identified described the process or outcome of AMR stewardship initiatives, or focused on policy aspects of AMR prevention, mitigation or management, beyond noting policy changes with respect to antimalarial use, for example, as a motivation for continuing to surveil for resistance phenotypes and genotypes.

Of the other types of antimicrobials covered in the identified studies, 68 papers reported data on antimalarials. Twenty-one studies reported primarily on resistance to artemisinin derivatives and/or common components in artemisinin-based combination therapies; 18 studies reported on resistance to multiple drugs or drug classes, with common combinations including chloroquine and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine or looking for multiple resistance genotypes. Fifteen studies focused primarily on resistance to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine or other antifolates or sulfonamides, and thirteen studies focused on genotypes or phenotypes associated specifically with chloroquine resistance. One study did not look at a specific antimalarial treatment, but associated strain diversity with treatment failure. Only three studies were identified that reported on antiviral resistance, of which two focused on the hepatitis virus (one on hepatitis C, and the other in hepatitis B in patients co-infected with HIV and undergoing antiretroviral therapy), and one focused on resistance to antiretroviral treatment. We located only a single study that discussed antifungals, on Cryptococcus neoformans.

There was similarly a heavy emphasis on the human health sector in the studies we identified, with 145 studies (over 88%) reporting data from human subjects, 12 studies focused on animal subjects (five focused on cattle, five on chickens’ and two on pigs/swine), while only six identified studies used a One Health approach. Of these, four studies looked at animal workers and their animals (three of which were cattle, and one was chickens), and two looked at animals and humans in the same geographic locations; the first covered a broad variety of animal species (cattle, goats, pigs, sheep and non-human primates), while the second focused more narrowly on pigs and birds, but also included environmental sampling from ponds, animal waste and sewage. This was the only study we identified that included environmental surveillance. All the veterinary and One Health studies focused on bacterial pathogens and/or antibiotic resistance, with the most commonly targeted pathogens being E. coli and Salmonella spp., with five and six studies, respectively, focusing exclusively on that pathogen. One study looked both at E. coli and Salmonella (a study in dairy cattle), and five studies looked more broadly across different types of bacterial pathogens or antibiotic resistance genes and phenotypes. Overall, there was a strong food safety focus, with all but one of the veterinary and One Health studies focused on livestock and food-producing animals; only one study also considered wildlife (non-human primates in national parks adjacent to agricultural areas and human habitation). We observed that the veterinary and One Health studies were all relatively recently published, with the earliest dating from 2013, and the majority published in 2019 and 2020.

Overall, only ten of the studies were laboratory-based, whereas the remaining 153 studies were done in the field, with recruitment specifically taking place in clinical/hospital settings. None of the human-focused studies appeared to include surveillance or recruitment at the community level, although all the veterinary and One Health studies were conducted in communities. Eighty-three of the studies produced results on resistance genotypes (Table 1), while 80 studies focused on simply looking at resistance profiles of the microbes, for example, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus, riphampicin-resistant tuberculosis, vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, beta lactamase-resistant E. coli and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. None of the articles we identified described the process or outcome of AMR stewardship initiatives, or focused on policy aspects of AMR prevention, mitigation or management, beyond noting policy changes with respect to antimalarial use, for example, as a motivation for continuing to surveil for resistance phenotypes and genotypes.

2. Study Characteristics

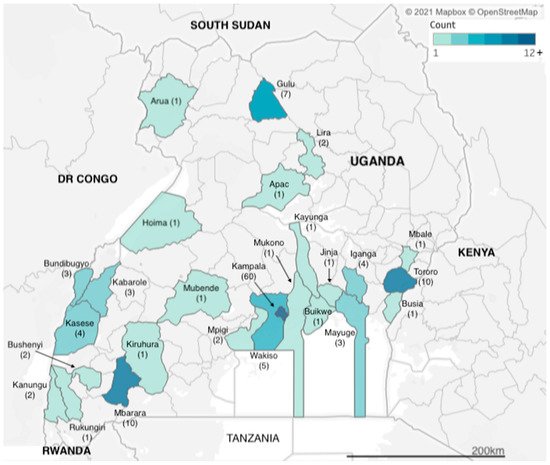

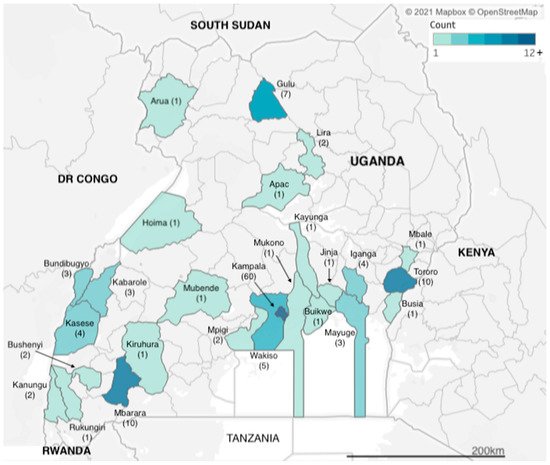

We identified articles related to AMR from research carried out across two dozen districts in Uganda (Figure 21). However, more than a third of the studies (n = 60) were carried out in Kampala, which is also the capital city and where the national referral hospital, Mulago Hospital, is located. The next three most frequently observed study sites were Tororo, Mbarara and Gulu districts (n = 10, n = 10 and n = 7 studies), each of which has a regional referral hospital, for western, eastern and northern Uganda respectively. Additional districts with multiple identified studies included Kasese in western Uganda and Iganga in eastern Uganda (both n = 4 studies), both of which have large district hospitals that serve large communities; Bundibugyo and Kabarole districts (both n = 3 studies), which are situated in the western cattle corridor bordering the Democratic Republic of Congo. Studies carried out in Uganda totalled 155, while eight of the studies were multicountry studies, with Mayuge district (n = 3 studies) in eastern Uganda.

Figure 21.

Geographic distribution of included studies.

Figure 32.

Distribution of studies on different AMR types by publication year.

Table 1.

Resistance Genes Identified in the Included Studies.

| Resistance Type | Target Pathogen | Number of Studies | Examples of Resistance Genes Identified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial | E. coli | 7 | blaCTX-M, blaACT, arnA, integrons class 1 and 2, qnrS1, tetA, tetB, sul2, blaSHV, blaTEM | ||

| Staphylococcus | spp. | 8 | spa types t064, t037, SCCmec types I and IV, mecA, aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2′’)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, ant(4′)-Ia, blaZ, mecA, vanA, vanB1 | ||

| Streptococcus | spp. | 3 | dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), folA and folP genes, | ||

| Salmonella | spp. | 2 | blaTEM-1,cmlA, tetA, qnrS, sul1, dhfrI, dhfrVII | ||

| Mycobacterium | spp. | 5 | Mutation gyrA Genotype Uganda I and II has Thr80Ala (acc/gcc), rpoB gene mutations | ||

| Klebsiella | spp. | 1 | blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEM | ||

| Enterococcus | spp. | 1 | EBC, FOX, ACC, CIT, DHA, MOX | ||

| Antimalarial | Plasmodium | falciparum | 55 | Pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F and D1246Y, Pfpm2, PfKelch13, plasmepsin2 gene, pfcrt 76T, Pfdhfr, Pfdhps | |

| Antiviral | Hepatitis C virus | 1 | g4 and g7 strains contain nonstructural (ns) protein 3 and 5A polymorphisms associated with resistance to DAAs | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | 1 | rtM204V/I mutations | |||

| HIV | 1 | Thymidine analog mutations, M184V |

References

- Clarke, C.R. Antimicrobial Resistance. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 36, 987–1001.

- Morrison, L.; Zembower, T.R. Antimicrobial Resistance. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 30, 619–635.

- Boucher, H.W.; Talbot, G.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Edwards, J.E.; Gilbert, D.; Rice, L.B.; Scheld, M.; Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1–12.

- Kuehn, B.M. “Nightmare” Bacteria on the Rise in US Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 309, 1573–1574.

- Walsh, T.R.; Toleman, M.A. The Emergence of Pan-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens Merits a Rapid Global Political Response. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1–3.

- Vikesland, P.; Garner, E.; Gupta, S.; Kang, S.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Zhu, N. Differential Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance across the World. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 916–924.

- Byarugaba, D.K. Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries and Responsible Risk Factors. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2004, 24, 105–110.

- UNAS. Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Anaysis; Uganda National Academy of Sciences: Kampala, Uganda, 2015; ISBN 9789970424108.

- Odoi, R.; Joakim, M.; Resistance, A. Anti-Microbial Resistance in Uganda. AMR 2019, 28–30. Available online: (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- WHO | Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. In Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Livestock and Companion Animals; American Society of Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 521–547.

- Uganda | Data. Available online: (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Okech, T.C. Analytical Review of Health Care Reforms in Uganda and Its Implication on Health Equity. World J. Med. Med. Sci. Res. 2014, 2, 55–62.

- Mbonye, A.K.; Buregyeya, E.; Rutebemberwa, E.; Clarke, S.E.; Lal, S.; Hansen, K.S.; Magnussen, P.; LaRussa, P. Prescription for Antibiotics at Drug Shops and Strategies to Improve Quality of Care and Patient Safety: A Cross-Sectional Survey in the Private Sector in Uganda. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010632.

- Ikwap, K.; Erume, J.; Owiny, D.O.; Nasinyama, G.W.; Melin, L.; Bengtsson, B.; Lundeheim, N.; Fellström, C.; Jacobson, M. Salmonella Species in Piglets and Weaners from Uganda: Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance and Herd-Level Risk Factors. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 115, 39–47.

- Uganda National Academy of Sciences (UNAS) Antimicrobial Resistance National Action Plans. Gov. Uganda 2016, 2015, 1–16.

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of Uganda: Mission Report: June 26–30; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; p. 75.

More