Bisindoles are structurally complex dimers and are intriguing targets for partial and total synthesis. They exhibit stronger biological activity than their corresponding monomeric units. Bisindole alkaloids are naturally occurring alkaloids containing two indole nuclei and are the products of late-stage biosynthetic processes in higher plants by combining two monomeric units. Depending on the monomeric units involved, bisindoles can be a homo- or heterodimer. As a result, bisindole alkaloids comprise much higher structural complexity than both of the monomeric units that comprise them. Alstonia, a major genus in the Apocynaceae family of plants, has more than 150 species and is found all over the world. Robert Brown named it in 1811 in honor of Charles Alston (1685–1760), an eminent botanist at the University of Edinburgh. The Alstonia genus’ trees and shrubs are prevalent in the tropical and subtropical parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia. They contribute significant pharmacological activity, including anticancer, antileishmanial, antimalarial, antitussive, antiviral, antiarthritic, and antibacterial activities.

- Apocynaceae

- Alstonia species

- Sarpagine-macroline-ajmaline type indole alkaloids

- Pleiocarpamine

- Bisindole synthesis

- Isolation of bisindoles

- Bioactivity of bisindoles

1. Bisindole Alkaloids in drug discovery

Nature has been a substantial and sustainable pool of biologically active compounds. Since ancient times natural product extracts (in crude form) have been used in traditional and folk medicines in many countries. In modern times pure (isolated) natural products and their derivatives play an important role in drug discovery, as indicated by their prevalence in approved drugs for clinical use. Out of the 1881 newly FDA-approved drugs over the last four decades (1 January 1981 to 30 September 2019), a significant portion comprising 506 (26.9%) were either natural products or derived from or inspired by natural products [1]. It is expected that the advent of modern and innovative technologies such as computational software, cheminformatics, artificial intelligence, automation, and quantum computing will further boost natural product-based drug discovery. A synergy among these technological milestones would accelerate hit to lead to clinic pathways of drug discovery, and natural products are expected to remain an important source [2]. Moreover, pharmacophores and their unique stereochemical interactions with natural products may stimulate more demanding targets such as protein–protein interactions in the near future and open up a new avenue in modern drug discovery [3]. The majority of biologically active natural products are produced in plants, known traditionally as medicinal plants. Alkaloids, the most important class of natural products with structural diversity and significant pharmacological effects, are mainly found in higher plants such as the Apocynaceae, Ranunculaceae, Papaveraceae, and Leguminosae families [4]. These natural products, along with flavonoids, fatty acids, etc., are the major classes of secondary metabolites that are believed to be parts of the plants’ defense mechanism. To date, many monoterpenoid indole and bisindole alkaloids have been found in the Alstonia genus [5]. Modern clinical application of many of these alkaloids are similar to their traditional or folklore applications; for example, cocaine and morphine were used as anesthetics while caffeine and nicotine were used as stimulants [6]. Recently, Fielding et al. illustrated that several anti-coronavirus alkaloids showed potential therapeutic value against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in their in silico studies [7].

2. Isolation and Plant' Morphology of Bisindoles from Alstonia Species

| Macroline-macroline type | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Macroline-sarpagine type | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Macroline-ajmaline type | ||

|

|

|

| Macroline-pleiocarpamine type | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Bisindoles | Alstonia Species |

Morphology and References |

|---|---|---|

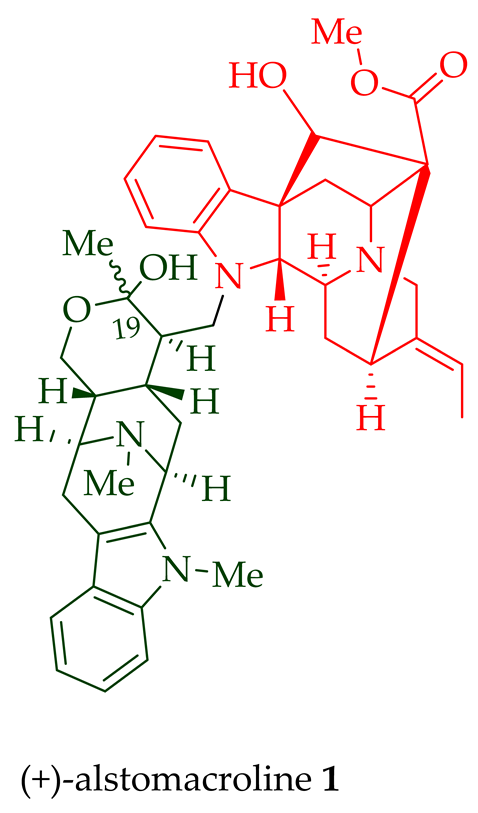

| (+)-Alstomacroline 1 | A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | Leaves, stem-bark, and root-bark [13][14] |

| A. macrophylla | Bark [12] | |

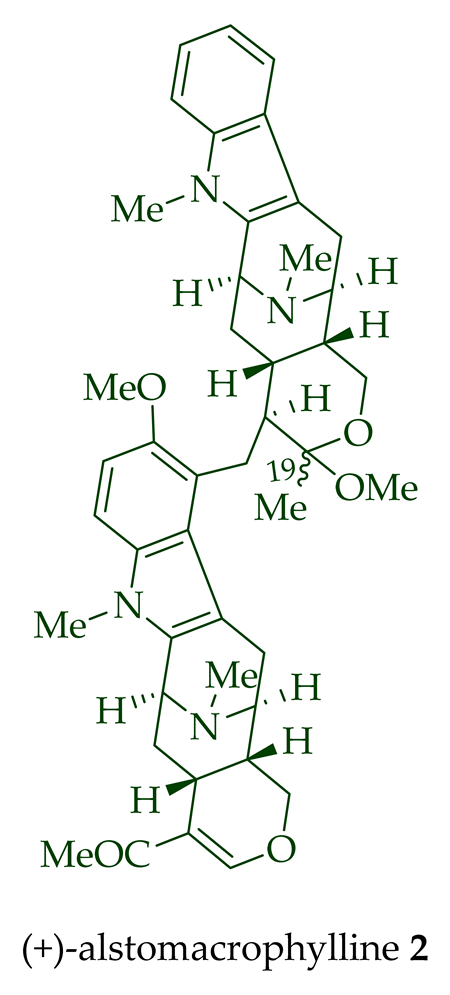

| (+)-Alstomacrophylline 2 | A. macrophylla | Bark [13] |

| A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | Leaves, stem-bark, and root-bark [14] | |

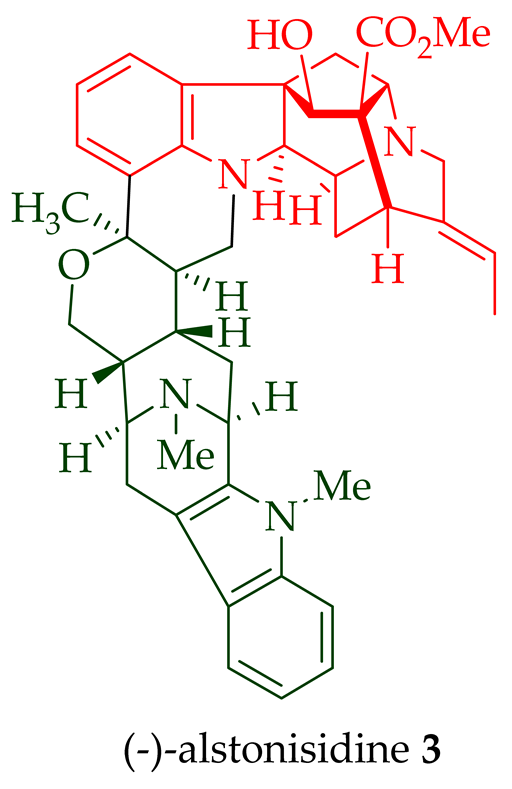

| (−) Alstonisidine 3 | A. muelleriana | Bark [15][16] |

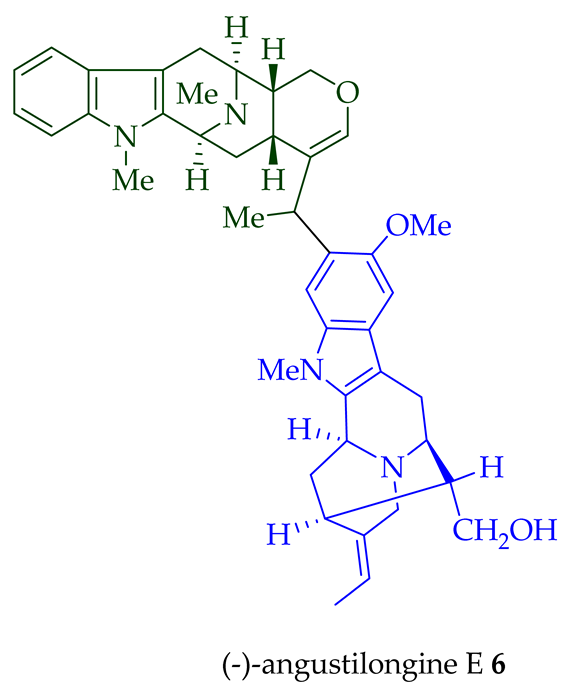

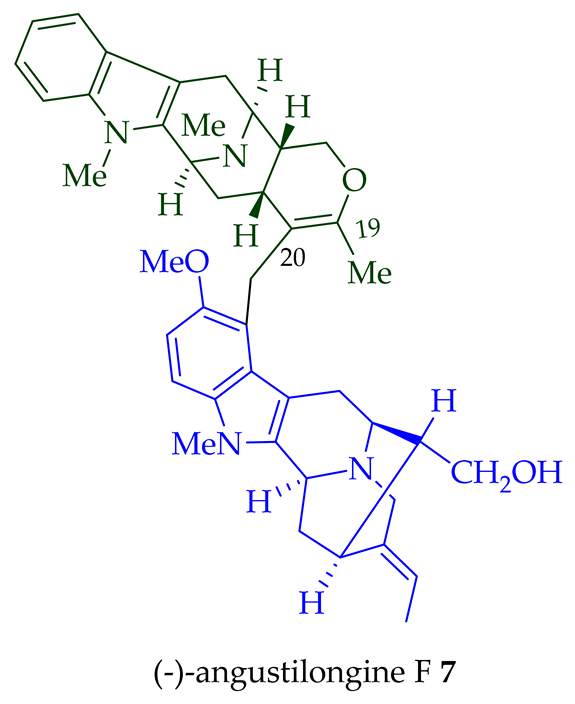

| (−)-Angustilongine E 6 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

| (−)-Angustilongine F 7 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

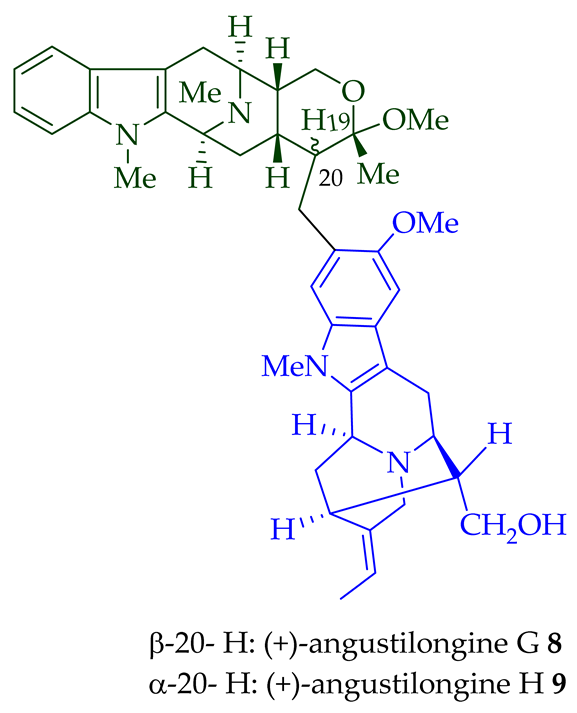

| (+)-Angustilongine G 8 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

| (+)-Angustilongine H 9 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

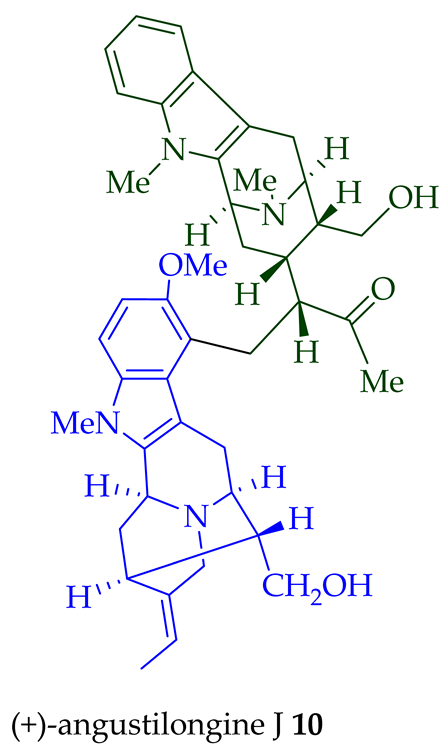

| (+)-Angustilongine J 10 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

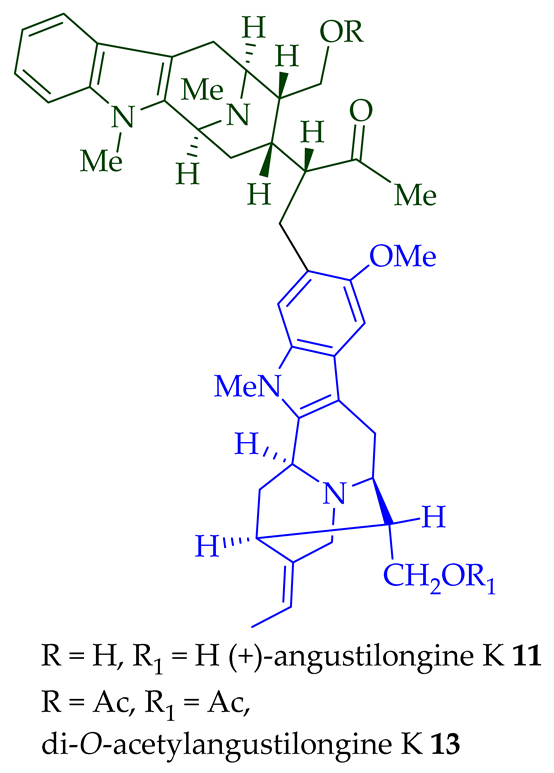

| (+)-Angustilongine K 11 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

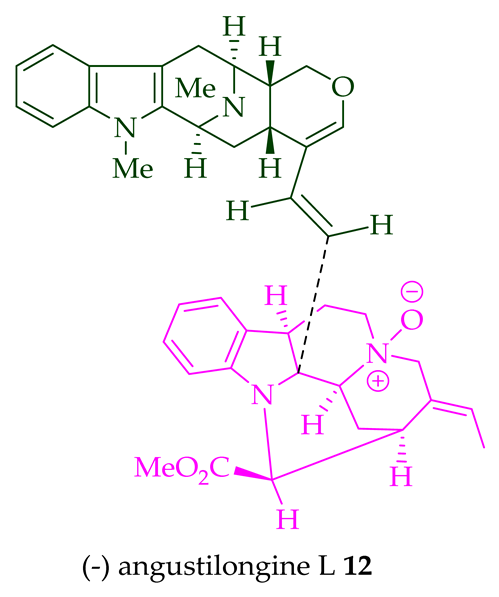

| (−)-Angustilongine L 12 | A. penangiana | Stem-bark [18] |

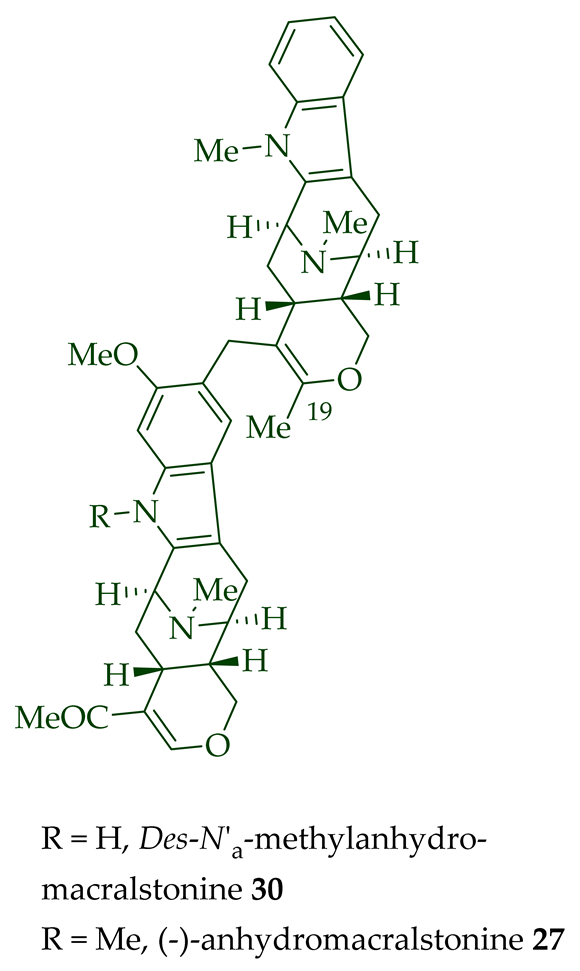

| (−)-Anhydromacralstonine 27 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| (+)-Des-N’a-Methylanhydromacralstonine 30 | A. muelleriana | Bark [14] |

| A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [28] | |

| A. muelleriana | Leaves, stem-bark and root-bark [14][30] | |

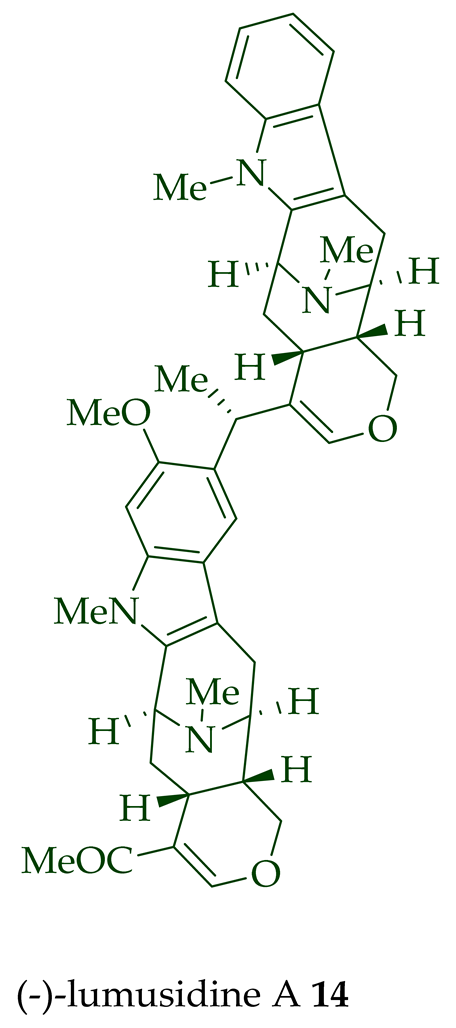

| (−)-Lumusidine A 14 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [12] |

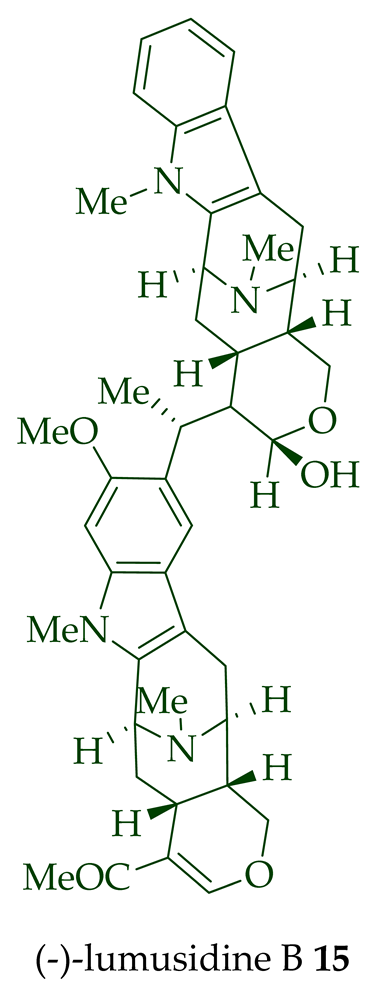

| (−)-Lumusidine B 15 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [12] |

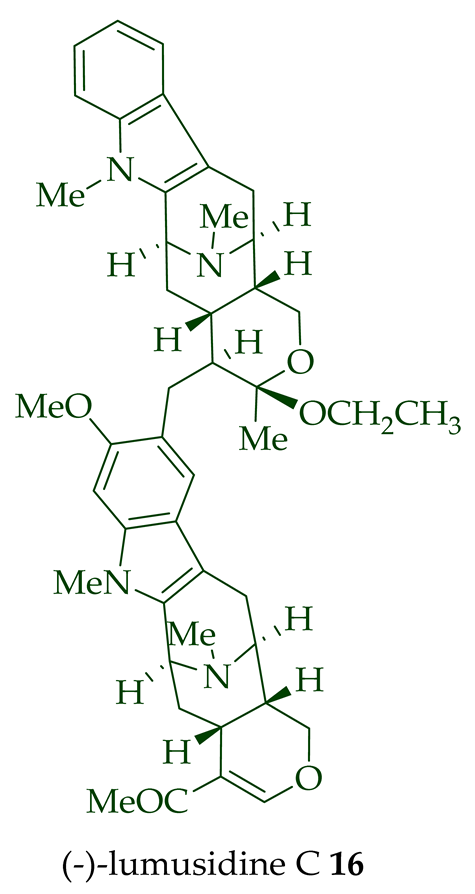

| (−)-Lumusidine C 16 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [12] |

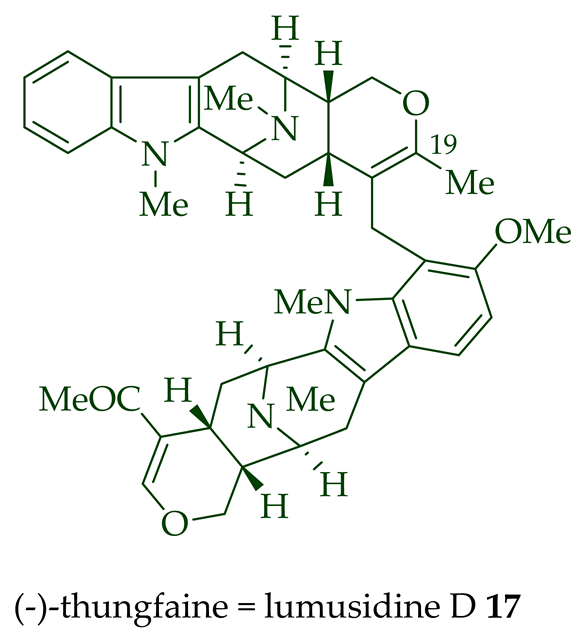

| (−)-Lumusidine D 17 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [12] |

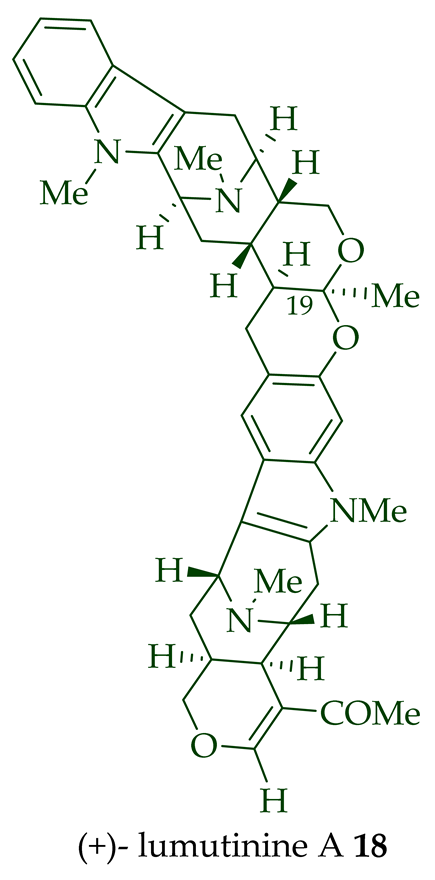

| (+)-Lumutinine A 18 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [21] |

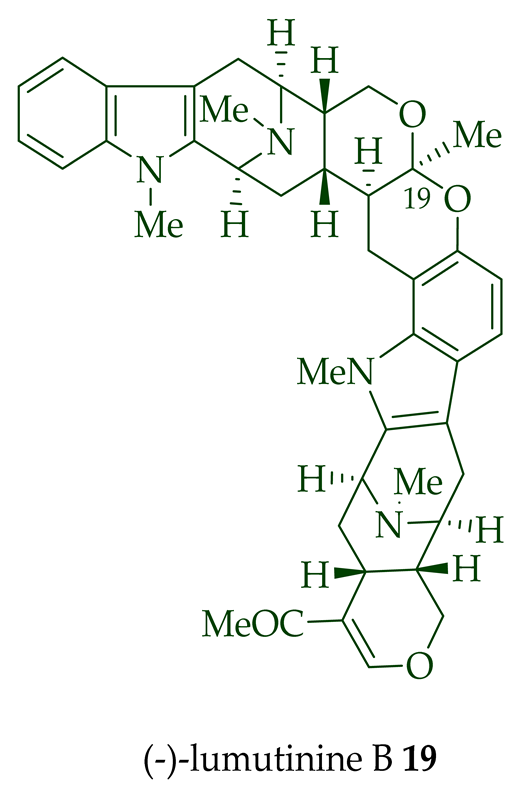

| (−)-Lumutinine B 19 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [21] |

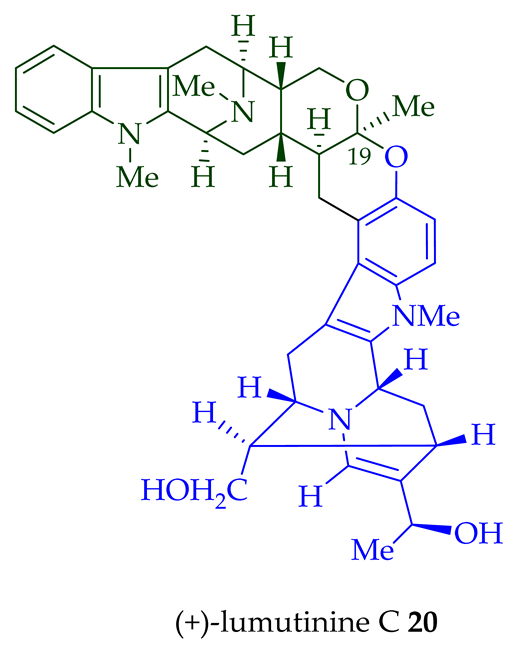

| (+)-Lumutinine C 20 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [21] |

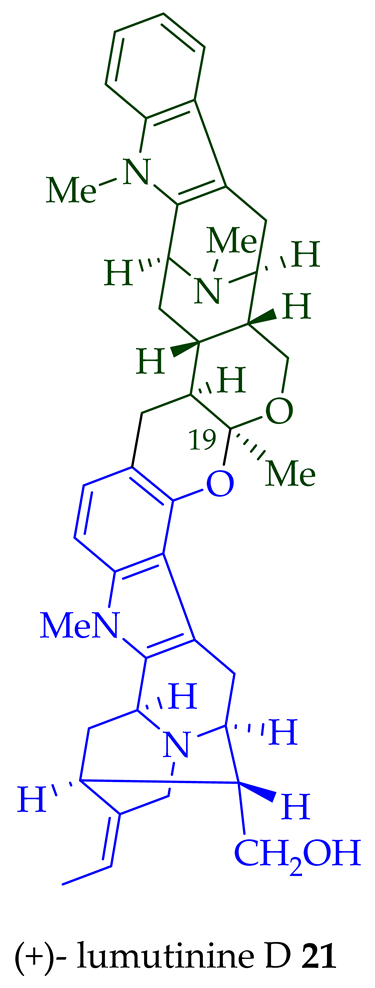

| (+)-Lumutinine D 19 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [21] |

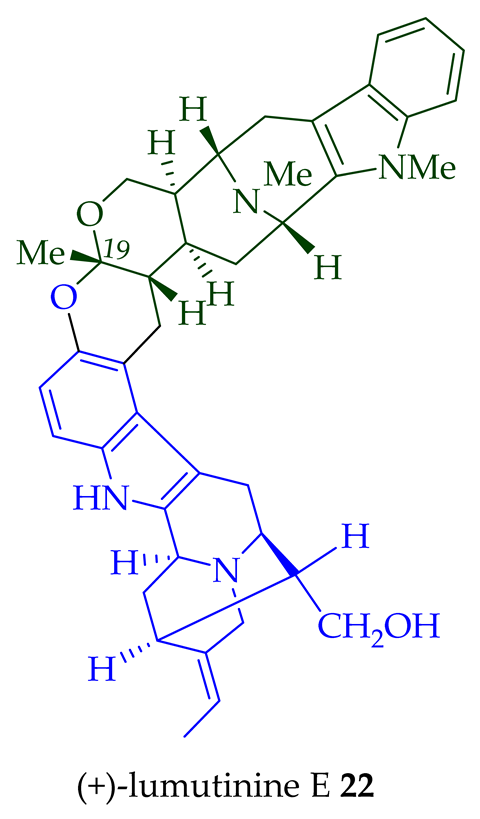

| (+)-Lumutinine E 21 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

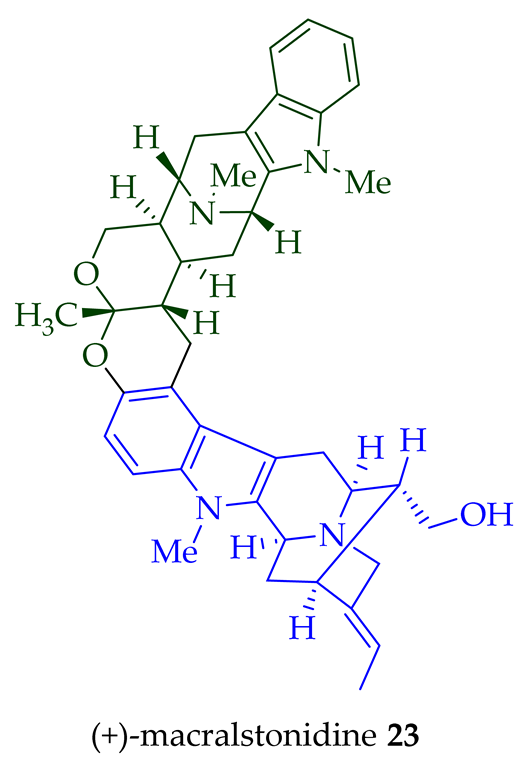

| (+)-Macralstonidine 23 | A. macrophylla | Bark [24][25] |

| A. somersentenis | Bark [24] | |

| A. spectabilis | Bark [26] | |

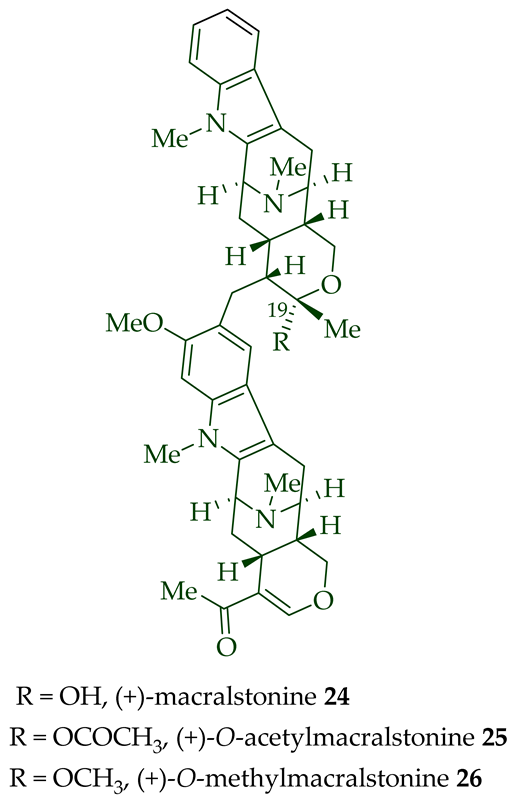

| (+)-Macralstonine 24 | A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | Leaves, stem-bark and root-bark [13] |

| (+)-O-Acetylmacralstonine 25 | A. macrophylla | [24][25][27][28][29] |

| A. angustifolia | [31] | |

| A. muelleriana | [30] | |

| A. glabriflora Mgf. | [26] | |

| A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | [14] | |

| (+)-O-Methylmacralstonine 26 | A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | [14] |

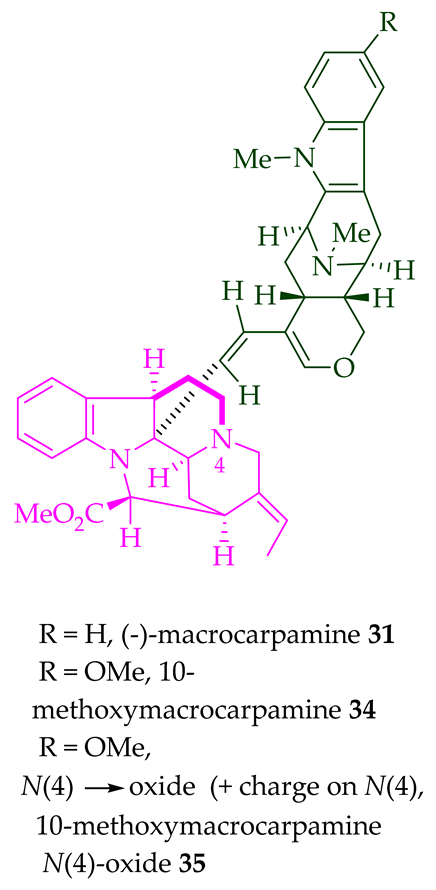

| (+)-Macrocarpamine 31 | A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | Leaves, stem-bark, and root-bark [14] |

| A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] | |

| 10-Methoxy macrocarpamine 34 | A. angustifolia | Leaves [36] |

| 10-Methoxy macrocarpamine 4′-N-oxide 35 | A. angustifolia | Leaves [36] |

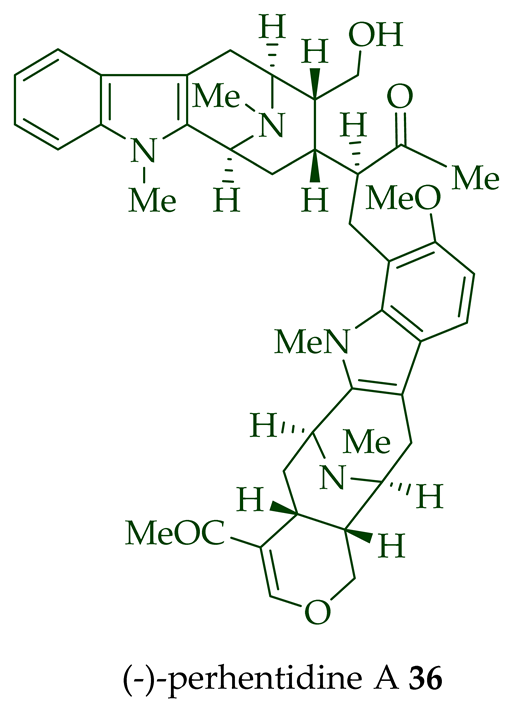

| (−)-Perhentidine A 36 | A. macrophylla and A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23][28] |

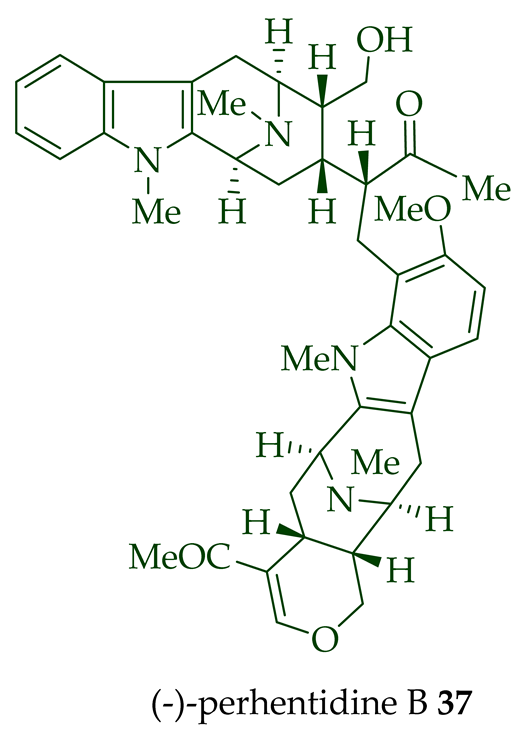

| (−)-Perhentidine B 37 | A. macrophylla and A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [28] |

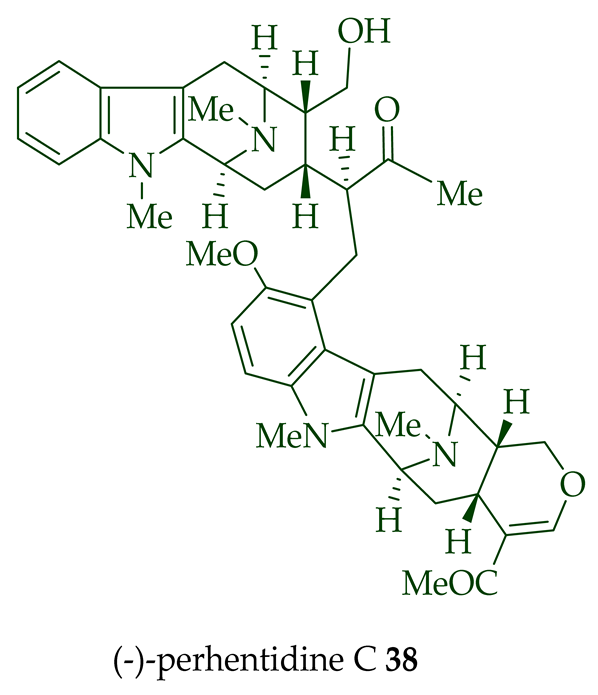

| (−)-Perhentidine C 38 | A. macrophylla and A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23][28] |

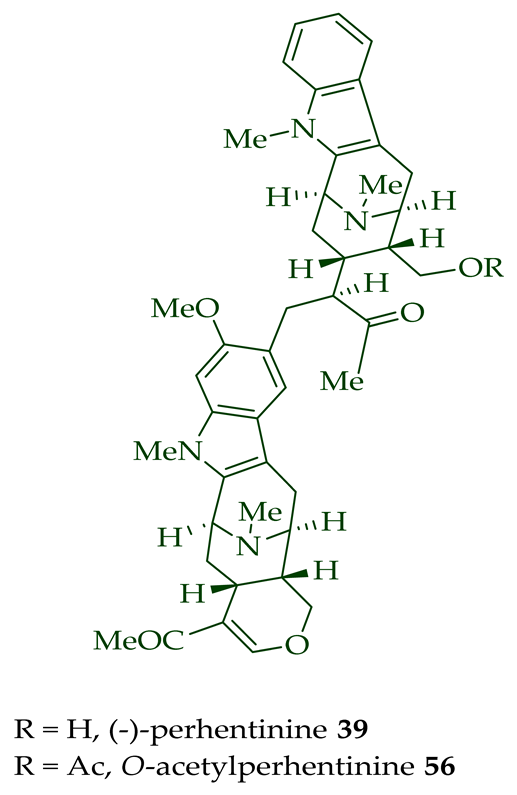

| (−)-Perhentinine 39 | ||

| 12 | ||

| ] | ||

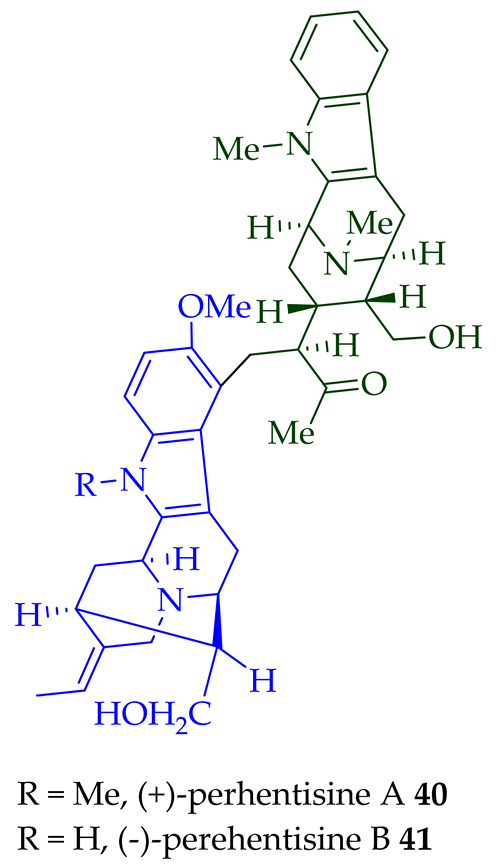

| (+)-Perhentisine A 40 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| (−)-Perhentisine B 41 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

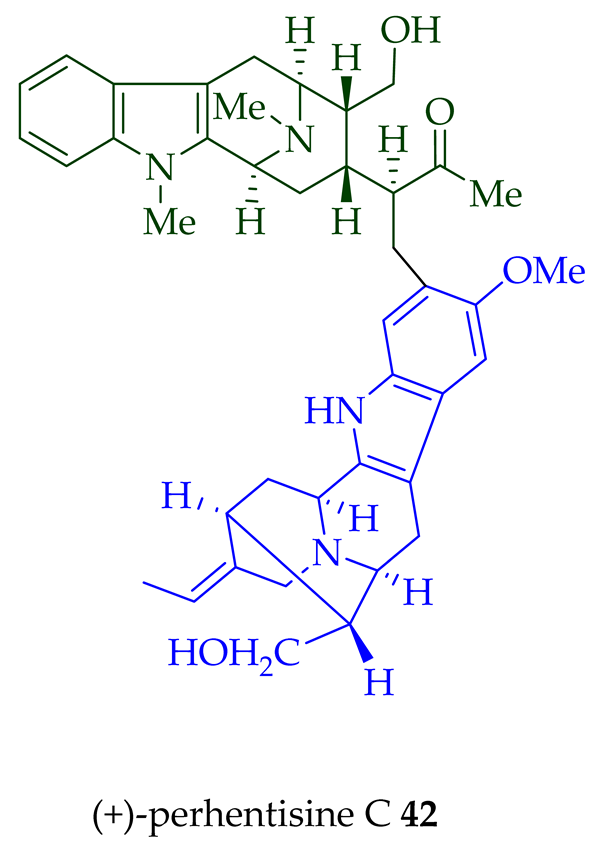

| (+)-Perhentisine C 42 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| A. muelleriana | Leaves and stem-bark [32] | |

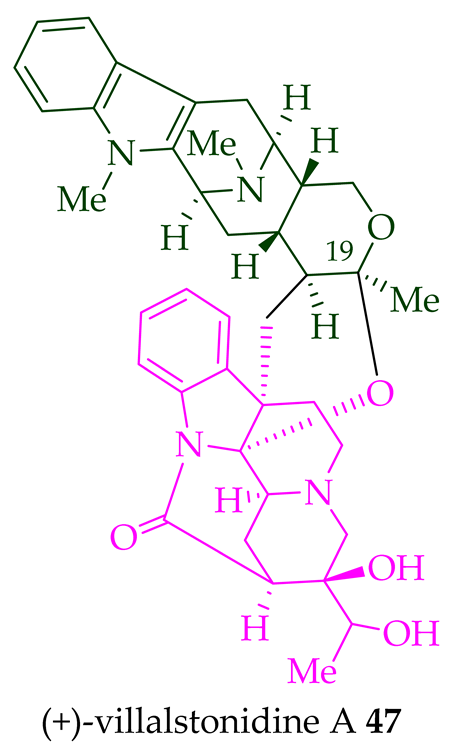

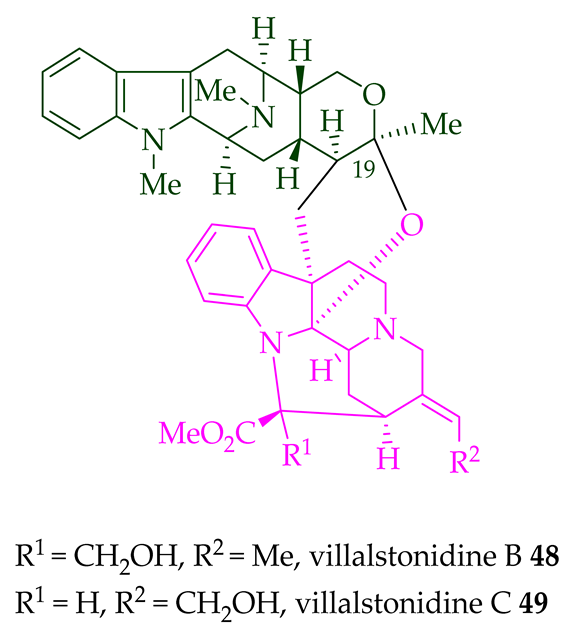

| (+)-Villalstonidine A 47 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| (+)-Villalstonidine B 48 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [22] | |

| (+)-Villalstonidine C 49 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

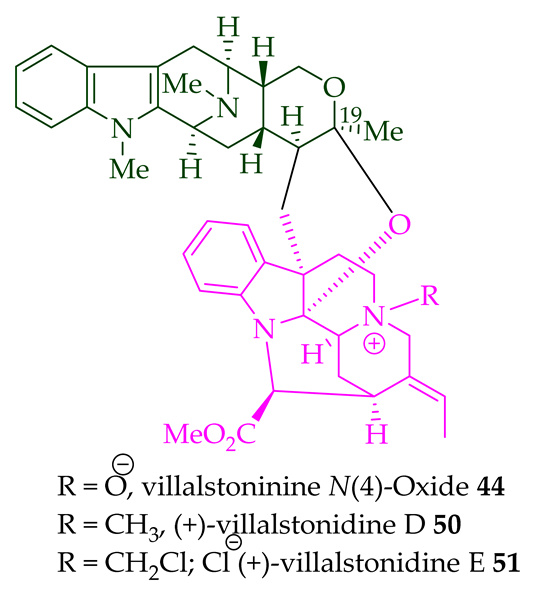

| (+)-Villalstonidine D 50 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| (+)-Villalstonidine E 51 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

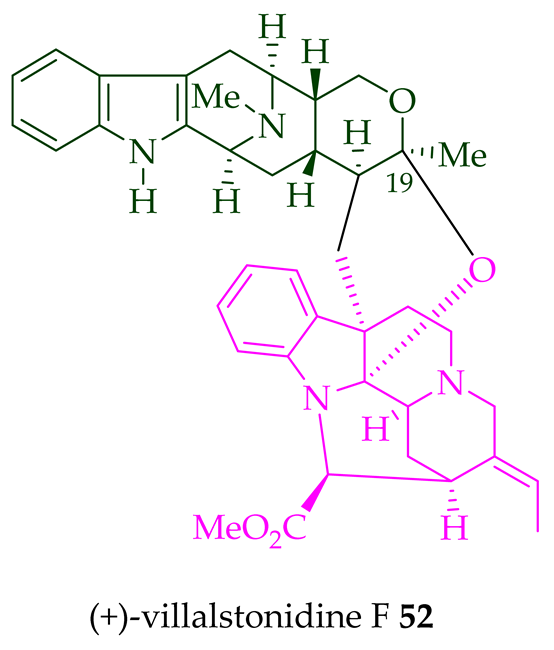

| (+)-Villalstonidine F 52 | A. macrophylla | Stem-bark [22] |

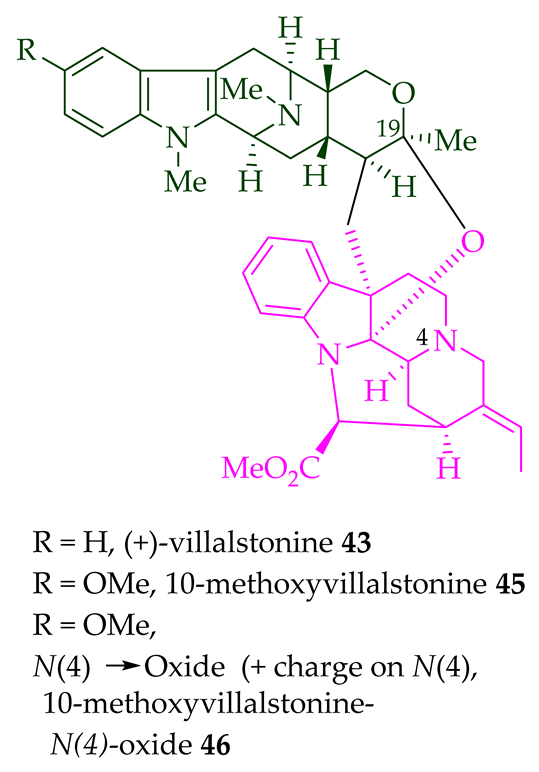

| (+)-Villalstonine 43 | A. angustifolia | Leaves and stem-bark [23][31][34][36] |

| A. macrophylla | [36] | |

| A. villosa | [36] | |

| A. verticillosa | [36] | |

| A. somersentensis | [36] | |

| Villalstonine N(4)-oxide 44 | A. angustifolia | Stem-bark [23] |

| A. scholaris, A. glaucescens, and A. macrophylla extracts | Leaves, stem-bark, and root-bark [14][25][27][33] | |

| (+)-10-Methoxy villalstonine 45 | A. angustifolia | Leaves [36] |

| 10-Methoxy villalstonine 4′-N-oxide 46 | A. angustifolia | Leaves [36] |

3. Bioactivity of Bisindoles from Alstonia Species

Bisindoles |

Bioactivity |

References |

|---|---|---|

| (+)-Alstomacroline 1 | Antimalarial, with IC50 values of 1.12 ± 0.35 and 10.0 ± 0.4 μM against the K1 strain and T9-96 strain of P. falciparum, respectively. | [14] |

| (+)-Alstomacrophylline 2 | Antimalarial, with an IC50 value of 1.10 ± 0.30 μM against the K1 strain of P. falciparum. | [14] |

| Angustilongines E, F, G, H, J, and K (6–11) | Anticancer, cytotoxic against various human cancer cell lines including KB, vincristine-resistant KB, HCCT 116, PC-3, MDA-MB-231, LNCaP, MCF7, HT-29, and A549 cells with IC50 values ranging from 0.02 to 9.0 μM. | [18] |

| (−)-Lumusidine A, B, and C (14–16) | Anticancer, moderately cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 values of 0.16, 0.70, and 1.19 μg/mL (μM), respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| (−)-Lumusidine D 17 | Anticancer, cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 5.03 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. |

[12] |

| Lumutinine A, B, C, D, and E (18–22) |

Anticancer, moderately cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 0.21, 0.10, 4.61, 3.93, and 2.74 μg/mL (μM) values, respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| (+)-Macralstonine 24 | Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 1.71 μg/mL (μM) value. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| Antimalarial, active against the K1 strain of P. falciparum with an IC50 8.92 ± 2.95 μM value. | [14] | |

| (−)-Anhydromacralstonine 27 | Anticancer, moderately cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 0.44 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. |

[12] |

| (+)-O-Acetyl macralstonine 25 | Antimalarial, with IC50 values 0.53 ± 0.09 and 12.4 ± 1.6 (μM) against the K1 strain and T9-96 strain of P. falciparum, respectively. | [14] |

| (+)-O-Methyl macralstonine 26 | Antimalarial, active against the K1 strain of P. falciparum with an IC50 0.85 ± 0.20 μM value. | [14] |

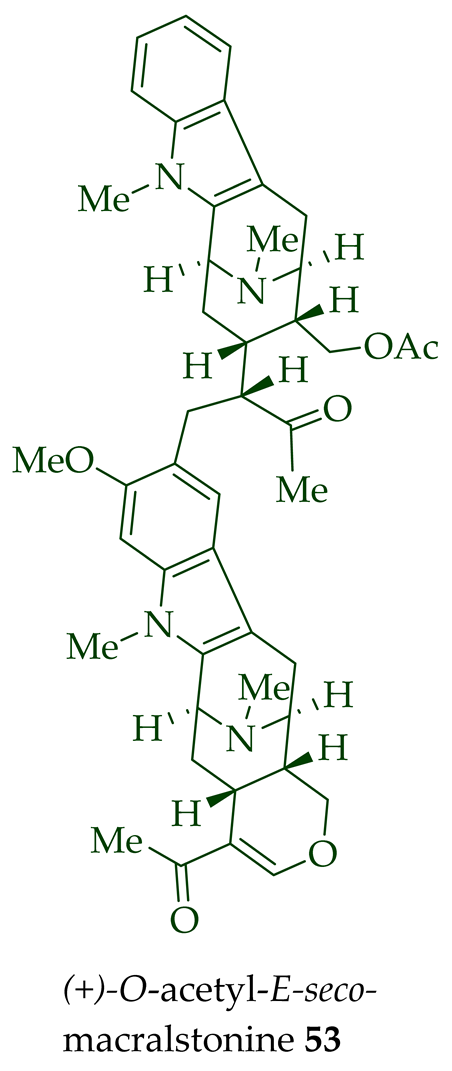

| O-Acetyl-E-seco-macralstonine 53 | Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 0.27 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| (−)-Perhentidine A 36 and (-)-perhentidine B 37 | Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 values of 2.29 and 0.84 μg/mL (μM), respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

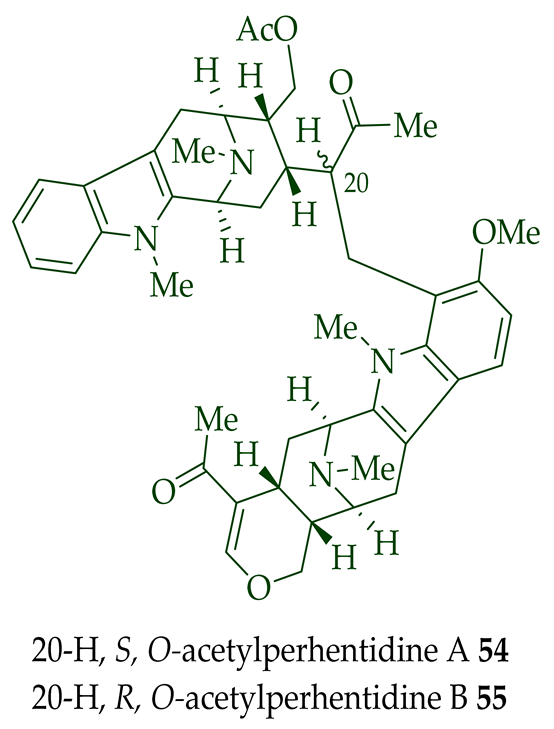

| (−)-O-Acetylperhentidine A 54 and (-)-O-Acetylperhentidine B 55 | Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 0.36 and 0.28 μg/mL (μM) values, respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| (−)-Perhentinine 39 and O-Acetylperhentinine 56 | Anticancer, cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 values of 0.52 and 0.30 μg/mL (μM), respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. |

[12] |

| (+)-Macralstonidine 23 | Anticancer, moderately cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 0.13 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| (+)-Macrocarpamine 21 | Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 0.53 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| Strong antimalarial activity against the K1 strain of P. falciparum with an IC50 value of 0.36 ± 0.06 μM. Active against the T9-96 strain of P. falciparum with an IC50 >39 μM value. |

[14] | |

| Strong antiprotozoal activity in vitro against E. histolytica and P. falciparum with ED50 8.12 (95% C.I.) μM and ED50 9.36 (95% C.I.) μM values, respectively. | [38] | |

| (+)-Villalstonine 43 | Anticancer, cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with an IC50 value of 0.42 μg/mL (μM). The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| Anticancer, cytotoxic against the HT-29 cell line with an ED50 8.0 μM value (paclitaxel was used as the positive control). | [34] | |

| Antimalarial, with IC50 values of 0.27 ± 0.06 and 0.94 ± 0.07 μM against the K1 strain and T9-96 strain of P. falciparum, respectively. | [14] | |

| Antiamoebic activity against E. histolytica with an ED50 of 2.04 μM. | [38] | |

| Villalstonine N(4)-oxide 44 | Antileishmanial activity against promastigotes of L. mexicana with an IC50 value of 80.3 μM (amphotericin B was used as the positive control). | [34] |

| Antimalarial, active against the K1 strain of P. falciparum with an IC50 10.7 ± 1.9 (μM) value. | [14] | |

| (+)-Villalstonidine B 48 and (+)-villalstonidine F 52 |

Anticancer, strongly cytotoxic in KB/VJ300 cells with IC50 values of 0.35 and 5.64 μg/mL (μM), respectively. The assay with 0.12 μM added vincristine did not influence KB/VJ300 cell growth. | [12] |

| A. macrophylla | ||

| (+)-Villalstodinine D 50 | Antileishmanial, active against promastigotes of L. mexicana with an IC50 value of 120.4 μM (amphotericin B was used as the positive control). | [34 |

| Stem-bark | ||

| [ | ||

| 12 | ||

| ] | ||

| ] | ||

| (+)-Villalstonidine E 51 | Anticancer, cytotoxic against HT-29 cell lines with an ED50 6.5 μM value (paclitaxel was used as the positive control). | [34] |

| Antileishmanial against promastigotes of L. mexicana with an IC50 78 μM value (amphotericin B was used as the positive control). | [34] | |

| A. angustifolia | ||

| Leaves | ||

| [ | ||

| 12 | ] | |

| A. macrophylla | Leaves [ |

5. Conclusions

References

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803.

- Thomford, N.E.; Senthebane, D.A.; Rowe, A.; Munro, D.; Seele, P.; Maroyi, A.; Dzobo, K. Natural products for drug discovery in the 21st century: Innovations for novel drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1578.

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129.

- Lu, J.J.; Bao, J.L.; Chen, X.P.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y.T. Alkaloids isolated from natural herbs as the anticancer agents. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 485042.

- Paul, A.T.; George, G.; Yadav, N.; Jeswani, A.; Auti, P.S. Pharmaceutical Application of Bio-actives from Alstonia Genus: Current Findings and Future Directions. In Bioactive Natural Products for Pharmaceutical Applications; Pal, D., Nayak, A.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 463–533.

- Calvert, M.B.; Sperry, J. Bioinspired total synthesis and structural revision of yuremamine, an alkaloid from the entheogenic plant Mimosa tenuiflora. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6202–6205.

- Fielding, B.C.; da Silva Maia Bezerra Filho, C.; Ismail, N.S.M.; de Sousa, D.P. Alkaloids: Therapeutic potential against human coronaviruses. Molecules 2020, 25, 5496.

- Namjoshi, O.A.; Cook, J.M. Chapter Two—Sarpagine and Related Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Knӧlker, H.-J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 76, pp. 63–169.

- Evans, B.E.; Rittle, K.E.; Bock, M.G.; DiPardo, R.M.; Freidinger, R.M.; Whitter, W.L.; Lundell, G.F.; Veber, D.F.; Anderson, P.S.; Chang, R.S.L.; et al. Methods for drug discovery: Development of potent, selective, orally effective cholecystokinin antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 2235–2246.

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, D.-B.; Zhou, P.-P.; Zhang, Q.-L.; Zhao, L.; Chen, J.-J.; Gao, K. Rauvomines A and B, two monoterpenoid indole alkaloids from Rauvolfia vomitoria. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3998–4001.

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Chen, Q.; Yang, G.-F. A review on recent developments of indole-containing antiviral agents. Eur. Med. Chem. 2015, 89, 421–441.

- Lim, S.H. Alkaloids from Alstonia Macrophylla. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malaya, Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, 2013.

- Keawpradub, N.; Houghton, P.J. Indole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Phytochemistry 1997, 46, 757–762.

- Keawpradub, N.; Kirby, G.C.; Steele, J.C.; Houghton, P.J. Antiplasmodial activity of extracts and alkaloids of three Alstonia species from Thailand. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 690–694.

- Elderfield, R.C.; Gilman, R.E. Alkaloids of Alstonia muelleriana. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 339–343.

- Burke, D.E.; Cook, G.A.; Cook, J.M.; Haller, K.G.; Lazar, H.A.; Le Quesne, P.W. Further alkaloids of Alstonia muelleriana. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 1467–1474.

- Hoard, L.G. The Crystal Structures of Altstonisidine, C42H48N4O4, and Anhydrous Cholesterol, C27H46O. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1977.

- Yeap, J.S.; Saad, H.M.; Tan, C.H.; Sim, K.S.; Lim, S.H.; Low, Y.Y.; Kam, T.S. Macroline-sarpagine bisindole alkaloids with antiproliferative activity from Alstonia penangiana. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 3121–3132.

- Hamaker, L.K.; Cook, J.M. The Synthesis of Macroline Related Sarpagine Alkaloids. In Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives; Pelletier, S.W., Ed.; Elsevier Publications: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 9.

- Kitajima, M.; Takayama, H. Chapter Four-Monoterpenoid Bisindole Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Knölker, H.-J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 76, pp. 259–310.

- Lim, S.-H.; Tan, S.-J.; Low, Y.-Y.; Kam, T.-S. Lumutinines A–D, linearly fused macroline–macroline and macroline–sarpagine bisindoles from alstonia macrophylla. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2556–2562.

- Lim, S.-H.; Low, Y.-Y.; Subramaniam, G.; Abdullah, Z.; Thomas, N.F.; Kam, T.-S. Lumusidines A− D and villalstonidine F, macroline–macroline and macroline–pleiocarpamine bisindole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Phytochemistry 2013, 87, 148–156.

- Tan, S.-J.; Lim, K.-H.; Subramaniam, G.; Kam, T.-S. Macroline–sarpagine and macroline–pleiocarpamine bisindole alkaloids from Alstonia angustifolia. Phytochemistry 2013, 85, 194–202.

- Sharp, T.M. 265. The alkaloids of Alstonia barks. Part II. A. macrophylla, wall., A. somersetensis, FM Bailey, A. verticillosa, F. Muell., A. villosa, blum. J. Chem. Soc. 1934, 1227–1232.

- Kishi, T.; Hesse, M.; Vetter, W.; Gemenden, C.; Taylor, W.; Schmid, H. Macralstonin. Helv. Chim. Acta 1966, 49, 946–964.

- Hart, N.; Johns, S.; Lamberton, J. Tertiary alkaloids of Alstonia spectabilis and Alstonia glabriflora (Apocynaceae). Aust. J. Chem. 1972, 25, 2739–2741.

- Keawprdub, N.; Houghton, P.; Eno-Amooquaye, E.; Burke, P. Activity of extracts and alkaloids of Thai Alstonia species against human lung cancer cell lines. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 97–101.

- Lim, S.-H.; Low, Y.-Y.; Tan, S.-J.; Lim, K.-H.; Thomas, N.F.; Kam, T.-S. Perhentidines A–C: Macroline–macroline bisindoles from Alstonia and the absolute configuration of perhentinine and macralstonine. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 942–950.

- Changwichit, K.; Khorana, N.; Suwanborirux, K.; Waranuch, N.; Limpeanchob, N.; Wisuitiprot, W.; Suphrom, N.; Ingkaninan, K. Bisindole alkaloids and secoiridoids from Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G. Don. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 798–804.

- Cook, J.; Le Quesne, P. Macralstonine from Alstonia muelleriana. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 437–439.

- Ghedira, K.; Zeches-Hanrot, M.; Richard, B.; Massiot, G.; Le Men-Olivier, L.; Sevenet, T.; Goh, S. Alkaloids of Alstonia angustifolia. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 3955–3962.

- Cook, J.M.; Le Quesne, P.; Elderfield, R. Alstonerine, a new indole alkaloid from Alstonia muelleriana. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1969, 1306–1307.

- Hesse, M.; Hürzeler, H.; Gemenden, C.; Joshi, B.; Taylor, W.; Schmid, H. Die Struktur des Alstonia-Alkaloides Villalstonin Vorläufige Mitteilung. Helv. Chim. Acta 1965, 48, 689–704.

- Pan, L.; Terrazas, C.; Muñoz Acuña, U.; Ninh, T.N.; Chai, H.; Carcache de Blanco, E.J.; Soejarto, D.D.; Satoskar, A.R.; Kinghorn, A.D. Bioactive indole alkaloids isolated from Alstonia angustifolia. Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 10, 54–59.

- Nordman, C.; Kumra, S. The structure of villalstonine1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 2059–2060.

- Buckingham, J.; Baggaley, K.H.; Roberts, A.D.; Szabo, L.F. Dictionary of Alkaloids with CD-ROM; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010.

- Keawpradub, N.; Eno-Amooquaye, E.; Burke, P.; Houghton, P. Cytotoxic activity of indole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 311–315.

- Wright, C.; Allen, D.; Cai, Y.; Phillipson, J.; Said, I.; Kirby, G.; Warhurst, D. In vitro antiamoebic and antiplasmodial activities of alkaloids isolated from Alstonia angustifolia roots. Phytother. Res. 1992, 6, 121–124.

- Gan, T.; Cook, J.M. General approach for the synthesis of macroline/sarpagine related indole alkaloids via the asymmetric Pictet-Spengler reaction: The enantiospecific synthesis of (−)-anhydromacrosalhine-methine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 5033–5036.

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, L.-H.; Hamaker, L.K.; Cook, J.M. Enantiospecific synthesis of (-)-alstonerine and (+)-macroline as well as a partial synthesis of (+)-villalstonine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 9027–9041.