Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Anita Giglio and Version 2 by Lily Guo.

Predator community structure is an important selective element shaping the evolution of prey defence traits and strategies. Carabid beetles are one of the most diverse families of Coleoptera, and their success in terrestrial ecosystems is related to considerable morphological, physiological, and behavioural adaptations that provide protection against predators. Their most common form of defence is the chemical secretion from paired abdominal pygidial glands that produce a heterogeneous set of carboxylic acids, quinones, hydrocarbons, phenols, aldehydes, and esters.

- defensive secretion

- ground beetles

- microscopy

- morphology

1. Introduction

The carabid beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) include approximately 40,000 described species that are ecologically important as predators in many ecosystems and range in feeding habits from generalist to specialists [1][2]. They are often used as indicators because they are extremely sensitive to environmental changes [3][4][5]. Furthermore, as generalist predators, ground beetles provide important ecosystem services by lowering populations of invertebrate pests and weed seeds [6][7]. However, carabids are consumed by a number of different species, including invertebrates and insectivorous vertebrates such as birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles [1]. Predator–prey interactions are likely the major driving force for the evolution of defences against predators in carabid beetles. Strategies to escape predatory attacks primarily include morphological adaptations, such as cryptic or warning coloration [8][9][10][11] and dorso-ventral flattening, large eyes, and long legs to escape [12], as well as secretion of chemical repellents [13][14][15]. Ground beetles possess a pair of abdominal glands called pygidial glands that produce defensive secretions. The main function of the pygidial glands is to defend against predators, but they also engage in biological activities such as facilitating the penetration of the defensive substances into the integument of the predator and inhibiting the growth of fungi and pathogens [16][17]. A few studies to date have examined the chemical compounds of pygidial gland secretions [18][19][20][21][22] and comparatively investigated their taxonomic significance [14][23][24][25][26]. We review the current state of knowledge on the morphology of pygidial glands in carabid beetles.

2. General Morphology

Forsyth [27] first proposed a comparative description of pygidial glands in 71 species from 34 tribes to define phylogenetic relationships within Carabidae. Currently, approximately 150 species from 43 tribes have been described (Table 1). The most commonly used examining technique to study pygidial gland morphology is light microscopy (LM). In addition, other techniques such as fluorescence (FM) microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and focused ion beam/scanning (FIB/SEM) electron microscopy, (TEM) transition electron microscopy, synchrotron radiation X-ray phase-contrast micro-tomography (SR-PhC micro-CT) are also applied.

Table 1. Summary of carabid species in which the pygidial gland morphology has been investigated and the method used for analyses. Abbreviations—CLSM: confocal laser scanning microscopy; FIB/SEM: focused ion beam/scanning electron microscopy; FM: fluorescence microscopy; LM: light microscopy; NLM: non linear microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; SR-PhC micro-CT: synchrotron radiation X-ray phase-contrast micro tomography.

| Tribe | Species | Methodology | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metriini | Metrius contractus | LM; FIB/SEM | [27][28] |

| Sinometrius turnai | LM; FIB/SEM | [28] | |

| Ozaeniini | Mystropomus regularis | LM | [26] |

| Paussini | Paussus favieri | LM; FM; FIB/SEM | [29] |

| P. laevifrons | LM | [27] | |

| Heteropaussus jeanneli | LM | [27] | |

| Cicindelini | Cicindela campestris, C. hibrida |

LM | [30] |

| Carabini | Calosoma oceanicum, C. schayeri |

LM | [26] |

| C. senegalense, C. problematicus |

LM | [27] | |

| C. sycophanta | LM | [31] | |

| Carabus (Tomocarabus) convexus | LM | [32] | |

| C. (Procustes) coriaceus | LM | [32][33] | |

| C. ullrichii | LM | [33] | |

| C. (Megodontus) violaceus | LM | [34] | |

| Cychrini | Cychrus caraboides rostratus | LM | [27] |

| Pamborini | Pamborus alternans | LM | [26] |

| Elaphrini | Elaphrus cupreus, Blethisa multipunctata | LM | [27] |

| Loricerini | Loricera pilicornis | LM | [27] |

| Omophronini | Omophron dentatum | LM | [27] |

| Nebriini | Eurynebria complanata,Leistus ferrugineus, Nebria brevicollis |

LM | [27] |

| N. psammodes | LM | [35] | |

| Notiophilini | Notiophilus substriatus | LM | [27] |

| Clivinini | Clivina basalis | LM | [26] |

| C. collaris, C. fossor |

LM | [27] | |

| Schizogenius lineolatus | LM | [23] | |

| Dyschiriini | Dyschirius globosus | LM | [27] |

| Pasimachini | Pasimachus elongatus | LM | [27] |

| P. subsulcatus | LM | [36][37] | |

| Carenini | Carenum bonelli, C. interruptum, C. tinctillatum |

LM | [26] |

| Laccopterum foveigerum, Philoscaphus tuberculatus |

LM | [26] | |

| Broscini | Eurylychnus blagravei, E. ollifi |

LM | [26] |

| Trechini | Thalassotrechus barbarae | LM | [27] |

| Trechus obtusus | LM | [27] | |

| Bembidiini | Bembidion lampros | LM | [20][27] |

| B. rupestre | LM | [27] | |

| Patrobini | Amblytelus curtus | LM | [26] |

| Patrobus longicornis | LM | [23] | |

| P. septentrionis | LM | [27] | |

| Morionini | Morion simplex | LM | [23] |

| Moriosomus seticollis | LM | [23] | |

| Perigonini | Diploharpus laevissimo | LM | [23] |

| Loxandrini | Loxandrus icarus | LM | [23] |

| L. longiformis | LM | [26] | |

| L. velocipes | LM | [23] | |

| Sphodrini | Calathus ambiguus | LM | [27] |

| Pristonychus terricola | LM | [27] | |

| Pterostichini | Abacomorphus asperulus | LM | [26] |

| Abaris anaea | LM | [23] | |

| Blennidus liodes | LM | [23] | |

| Castelnaudia superba | LM | [26] | |

| Cratoferonia phylarchus | LM | [26] | |

| Cratogaster melas | LM | [26] | |

| Cyclotrachelus sigillatus | LM | [23] | |

| Gasterllarius honestus | LM | [23] | |

| Incastichus aequidianus | LM | [23] | |

| Loxodactylus carinulatus | LM | [26] | |

| Myas coracinus | LM | [23] | |

| Notonomus angusribasis, N. crenulatus, N. miles, N. muelleri, N. opulentus, N. rainbowi, N. rainbowi, N. scotti, N. triplogenioides, N. variicollis |

LM | [26] | |

| Prosopogmus harpaloides | LM | [26] | |

| Pseudoceneus iridescens | LM | [26] | |

| Pterostichus (Cophosus) cylindricus | LM; NLM | [38] | |

| P. (Monoferonia) diligendus | LM | [23] | |

| P. externepunctatus roccai | LM | [35] | |

| P. fortis | LM | [25] | |

| P. luctuosus | LM | [23] | |

| P. madidus | LM | [39] | |

| P. melanarius | LM | [27] | |

| P. melas | SR-PHC MICRO-CT | [40] | |

| P. (Pseudomaseus) nigrita | LM; NLM | [38] | |

| Rhytisternus laevilaterus | LM | [26] | |

| Sarticus cyaneocinctus | LM | [26] | |

| Sphodrosomus saisseri | LM | [26] | |

| Trichosternus nudipes | LM | [26] | |

| Platynini | Agonumdorsale | LM | [27] |

| Zabrini | Amara aenea | LM | [27] |

| Curtonotus fulvus | LM | [27] | |

| Zabrus tenebriodes | LM | [27] | |

| Molopini | Abax parallelepipedus (sub:A. ater) | LM | [27][33] |

| Molops (Stenochoromus)montenegrinus | LM; NLM | [38] | |

| Harpalini | Bradycellus harpalinus | LM | [27] |

| Diaphoromerus edwardsi | LM | [26] | |

| Harpalus aeneus | LM | [27] | |

| H. pensylvanicus | CLSM | [41] | |

| Pseudophonus rufipes (sub:pubescens) | LM | [27] | |

| Licinini | Badister bipustulatus | LM | [27] |

| Dicrochile brevicollis, D. goryi |

LM | [26] | |

| Licinus depressus | LM | [27] | |

| Syagonix blackburni | LM | [26] | |

| Chlaeniini | Chlaenius australis | LM | [26] |

| C. cumatilis | LM | [27] | |

| C. inops | LM | [25] | |

| C. pallipes | LM | [25] | |

| C. velutinus | LM | [35] | |

| C. vestitus | LM | [27][35] | |

| Oodes amaroides | LM | [23] | |

| O. hehpioides | LM | [27] | |

| Panagaenini | Panagaeus crux-major | LM | [27] |

| Psecadius eustalactus | LM | [27] | |

| Masoreini | Masoreus wetterhlii | LM | [27] |

| Odacanthini | Colliuris melanura | LM | [27] |

| C. pensylvanica | LM | [23] | |

| Lebiini | Eudalia macleayi | LM | [26] |

| Metabletus foveatus | LM | [27] | |

| Movmolyce phyllodes | LM | [27] | |

| Galeritini | Galerita lecontei | LM | [42] |

| Anthiini | Anthia artemis | LM | [27] |

| Helluonini | Helluo costatus | LM | [26] |

| Catapieseini | Catapiesis attenuata, C. sulcipennis |

LM | [23] |

| Dryptini | Drypta dentata | LM | [27] |

| D. japonica | LM | [25] | |

| Pseudomorphini | Sphallomorpha colymbeioides | LM | [26] |

| Brachinini | Aptinus bombarda | LM; FM; FIB/SEM | [43] |

| A. crepitus | LM; FM; FIB/SEM | [43] | |

| A. displosor | LM | [27] | |

| Brachinus crepitans | LM | [27] | |

| B. elongatus | LM; FM; FIB/SEM; SEM | [43][44] | |

| B. sclopeta | LM; FM; FIB/SEM | [43] | |

| B. stenoderus | LM | [25] | |

| P. verticalis | LM | [26] | |

| Pheropsophus africanus, P. hispanus, P. occipitalis |

LM; FM; FIB/SEM | [43] | |

| P. lissoderus | LM | [27] | |

| P. verticalis | LM | [26] |

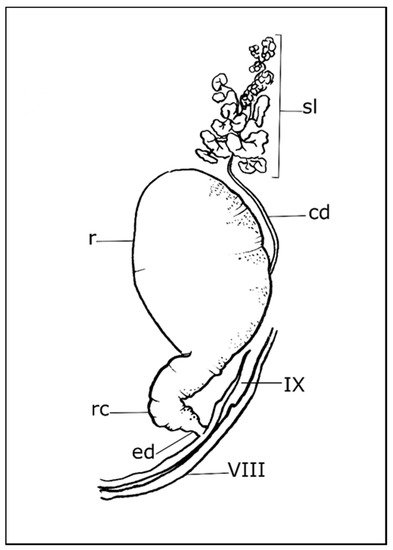

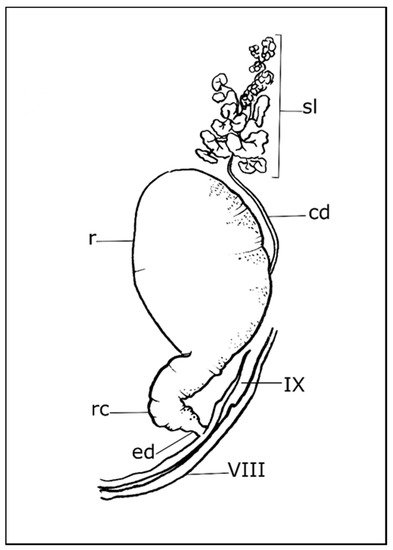

Each pygidial gland consists of a variable number of secretory lobes (acini), collecting duct, reservoir chamber, reaction chamber, and efferent duct (Figure 1). These glands (class 3 according to the classification of Noirot and Qhennedey [45][46]) are variable in structure and have been described in several species [27][39]. The lobe or acinus, which is spherical or elongated and enveloped in a thin basal lamina, is a cluster of secretory units, connected to the collecting duct by a conducting duct that drains secretions outward. The secretory unit consists of two parts, an elongated, cube-shaped secretory cell surrounding a receiving duct and a duct cell surrounding the conducting duct [27][28][29][43]. The receiving duct is a porous tube composed of one or more layers of epicuticle located in its extracellular space and bounded by microvilli. The collecting duct has an epithelial wall of flattened cells, lined by endocuticle, and a thin layer of epicuticle that is regularly folded into spiral ridges, annular arrays, or pointed peg-like projections, that reduce the volume of the lumen to control the free flow of secretion to the reservoir chamber [27][28][43]. The entrance of the collecting duct to the reservoir chamber is of great variability. It is located at the anterior or middle position in Scaritinae, Brachininae, and some Bembidiini, Pterostichini, Amarini, Carabini, Nebriini, Metriini, and Paussini [25][27][28][29][32][34][38]. While it is located near the entrance of the efferent duct in Harpalini, Agonini, Chlaeniini, Dryptini, Anthiini, Lebiini, Trachypachini, Omophronini, Loxandrini, Catapieseini, Galeritini, and Zuphini [23][25][27][42]. The reservoir chamber is a spherical, elongate, or bilobate compartment of variable size. Interwoven muscle bundles cover the outer wall and are connected to tracheal branches. The basal membrane supports flattened epithelial cells covered by a thin uniform layer of endo- and epicuticle. The muscular contraction regulates secretion through a valve that separates the reservoir from the reaction chamber. In Paussinae, Brachininae, and Carabinae, an accessory gland is located below the valve [27]. Secretions from the reservoir chamber are mixed with secretions from the accessory glands in the reaction chamber. The efferent duct leads from the reservoir chamber to the external orifice. The close association of the pygidial glands with the tracheal branches suggests a high aerobic metabolism.

Figure 1. Schematic drawing of a pygidial gland. cd: collecting duct; ed: efferent duct; r: reservoir chamber; rc: reaction chamber; sl: secretory lobe; VIII: eighth tergite; IX: ninth tergite (for more details of species listed in the text, see Forsyth (1972) [27]).

The external orifice is located dorso-laterally in the posterior part of the abdomen, near to the antero-lateral margin of the ninth tergite, and close to the tergo-sternal suture in Carabinae, Scaritinae, Paussinae, Elaphrinae, Broscinae, and Brachinini, or at the posterolateral margin of the eighth tergite in derived lineages, e.g., Trechinae and Harpalinae, and including Licinini, Chlaeniini, Panagaeini, Anthiini, Zabrini, Oodini, Pterostichini, and Agonini [27][47]. Differences in pygidial gland morphology between sexes have been reported in Cicindela campestris [30].

References

- Holland, J.M. The Agroecology of Carabid Beetles; Intercept Limited: Andover, UK, 2002; Volume 62, ISBN 1898298769.

- Lövei, G.L.; Sunderland, K.D. Ecology and behavior of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41, 231–256.

- Koivula, M.J. Useful model organisms, indicators, or both? Ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) reflecting environmental conditions. ZooKeys 2011, 287–317.

- Rainio, J.; Niemelä, J. Ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) as bioindicators. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 487–506.

- Avgın, S.S.; Luff, M.L. Ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) as bioindicators of human impact. Munis Entomol. Zool. 2010, 5, 209–215.

- De Heij, S.E.; Willenborg, C.J. Connected carabids: Network interactions and their impact on biocontrol by carabid beetles. BioScience 2020, 70, 490–500.

- Kulkarni, S.S.; Dosdall, L.M.; Willenborg, C.J. The role of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in weed seed consumption: A review. Weed Sci. 2015, 63, 355–376.

- Fukuda, S.; Konuma, J. Using three-dimensional printed models to test for aposematism in a carabid beetle. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 128, 735–741.

- Schultz, T.D. Tiger beetle defenses revisited: Alternative defense strategies and colorations of two neotropical tiger beetles, Odontocheila nicaraguensis Bates and Pseudoxycheila tarsalis Bates (Carabidae: Cicindelinae). Coleopt. Bull. 2001, 153–163.

- Hasegawa, M.; Taniguchi, Y. Visual avoidance of a conspicuously colored carabid beetle Dischissus mirandus by the lizard Eumeces okadae. J. Ethol. 1994, 12, 9–14.

- Brandmayr, P.; Bonacci, T.; Giglio, A.; Talarico, F.F.; Brandmayr, T.Z. The evolution of defence mechanisms in carabid beetles: A review. In Life and Time: The Evolution of Life and its History; Cleup: Padova, Italy, 2009; pp. 25–43. ISBN 9788861294110.

- Talarico, F.; Brandmayr, P.; Giglio, A.; Massolo, A.; Brandmayr, T.Z. Morphometry of eyes, antennae and wings in three species of Siagona (Coleoptera, Carabidae). ZooKeys 2011, 100, 203–214.

- Whitman, D.W.; Blum, M.S.; Alsop, D.W. Allomones: Chemicals for defense. Insect Def. Adapt. Mech. Strateg. Prey Predat. 1990, 289, 289–351.

- Dettner, K. Chemosystematics and evolution of beetle chemical defenses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1987, 32, 17–48.

- Giglio, A.; Brandmayr, P.; Talarico, F.; Brandmayr, T.Z. Current knowledge on exocrine glands in carabid beetles: Structure, function and chemical compounds. ZooKeys 2011, 100, 193–201.

- Evans, D.L.; Schmidt, J.O. Insect Defenses: Adaptive Mechanisms and Strategies of Prey and Predators; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 1438402201.

- Blum, M.S. Semiochemical parsimony in the Arthropoda. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41, 353–374.

- Lečić, S.; Ćurčić, S.; Vujisić, L.; Ćurčić, B.; Ćurčić, N.; Nikolić, Z.; Anelković, B.; Milosavljević, S.; Tešević, V.; Makarov, S. Defensive secretions in three ground-beetle species (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae). Proc. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2014, 51, 285–300.

- Rork, A.M.; Renner, T. Carabidae semiochemistry: Current and future directions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 1069–1083.

- Blum, M. Chemical defenses of Arthropods. In Chemical Defenses of Arthropods; Blum, M.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; p. 561. ISBN 978-0-12-108380-9.

- Erwin, T.L.; Ball, G.E.; Whitehead, D.R.; Halpern, A.L. Carabid Beetles: Their Evolution, Natural History, and Classification; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 9400996284.

- Dazzini-Valcurone, M.; Pavan, M. Glandole pigidiali e secrezioni difensive dei Carabidae (Insecta Coleoptera). Publicazioni Dell’istituto Di Entomol. Dell’universita Di Pavia 1980, 12, 1–36.

- Will, K.W.; Attygalle, A.B.; Herath, K. New defensive chemical data for ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae): Interpretations in a phylogenetic framework. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2000, 71, 459–481.

- Moore, B.P. Chemical defense in carabids and its bearing on phylogeny. In Carabid Beetles; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 193–203.

- Kanehisa, K.; Murase, M. Comparative study of the pygidial defensive systems of carabid beetles. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1977, 12, 225–235.

- Moore, B.P.; Wallbank, B.E. Chemical composition of the defensive secretion in carabid beetles and its importance as a taxonomic character. In Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London. Series B, Taxonomy; Wiley Online Library: Oxford, UK, 1968; Volume 37, pp. 62–72.

- Forsyth, D.J. The structure of the pygidial defence glands of Carabidae (Coleoptera). Trans. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1972, 32, 249–309.

- Muzzi, M.; Moore, W.; Di Giulio, A. Morpho-functional analysis of the explosive defensive system of basal bombardier beetles (Carabidae: Paussinae: Metriini). Micron 2019, 119, 24–38.

- Muzzi, M.; Di Giulio, A. The ant nest “bomber”: Explosive defensive system of the flanged bombardier beetle Paussus favieri (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2019, 50, 24–42.

- Forsyth, D.J. The structure of the defence glands of the Cicindelidae, Amphizoidae, and Hygrobiidae (Insecta: Coleoptera). J. Zool. 1970, 160, 51–69.

- Nenadić, M.; Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; Perić-Mataruga, V.; Ilijin, L.; Tešević, V.; Todosijević, M.; Vujisić, L.; Vesović, N.; et al. The pygidial gland secretion of the forest caterpillar hunter, Calosoma (Calosoma) sycophanta: The antimicrobial properties against human pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 977–985.

- Vesović, N.; Vujisić, L.; Perić-Mataruga, V.; Krstić, G.; Nenadić, M.; Cvetković, M.; Ilijin, L.; Stanković, J.; Ćurčić, S. Chemical secretion and morpho-histology of the pygidial glands in two Palaearctic predatory ground beetle species: Carabus (Tomocarabus) convexus and C. (Procrustes) coriaceus (Coleoptera: Carabidae). J. Nat. Hist. 2017, 51, 545–560.

- Nenadić, M.; Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; Perić-Mataruga, V.; Ilijin, L.; Tešević, V.; Vujisić, L.; Todosijević, M.; Vesović, N. Antimicrobial activity of the pygidial gland secretion of three ground beetle species (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae). Sci. Nat. 2016, 103, 34.

- Vesović, N.; Ćurčić, S.; Todosijević, M.; Nenadić, M.; Zhang, W.; Vujisić, L. Pygidial gland secretions of Carabus Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Carabidae): Chemicals released by three species. Chemoecology 2020, 30, 59–68.

- Balestrazzi, E.; Valcurone Dazzini, M.L.; De Bernardi, M.; Vidari, G.; Vita-Finzi, P.; Mellerio, G. Morphological and chemical studies on the pygidial defence glands of some Carabidae (Coleoptera). Naturwissenschaften 1985, 72, 482–484.

- Davidson, B.S.; Eisner, T.; Witz, B.; Meinwald, J. Defensive secretion of the carabid beetle Pasimachus subsulcatus. J. Chem. Ecol. 1989, 15, 1689–1697.

- Witz, B.W.; Mushinsky, H.R. Pygidial secretions of Pasimachus subsulcatus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) deter predation by Eumeces inexpectatus (Squamata: Scincidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1989, 15, 1033–1044.

- Vranić, S.; Ćurčić, S.; Vesović, N.; Mandić, B.; Pantelić, D.; Vasović, M.; Lazović, V.; Zhang, W.; Vujisić, L. Chemistry and morphology of the pygidial glands in four Pterostichini ground beetle taxa (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Pterostichinae). Zoology 2020, 142, 125772.

- Forsyth, D.J. The ultrastructure of the pygidial defence glands of the carabid Pterostichus madidus F. J. Morphol. 1970, 131, 397–415.

- Donato, S.; Vommaro, M.L.; Tromba, G.; Giglio, A. Synchrotron X-ray phase contrast micro tomography to explore the morphology of abdominal organs in Pterostichus melas italicus Dejean, 1828 (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2021, 62, 101044.

- Rork, A.M.; Mikó, I.; Renner, T. Pygidial glands of Harpalus pensylvanicus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) contain resilin-rich structures. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2019, 49, 19–25.

- Rossini, C.; Attygalle, A.B.; González, A.; Smedley, S.R.; Eisner, M.; Meinwald, J.; Eisner, T. Defensive production of formic acid (80%) by a carabid beetle (Galerita lecontei). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 6792–6797.

- Di Giulio, A.; Muzzi, M.; Romani, R. Functional anatomy of the explosive defensive system of bombardier beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Brachininae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2015, 44, 468–490.

- Arndt, E.M.; Moore, W.; Lee, W.K.; Ortiz, C. Mechanistic origins of Bombardier beetle (Brachinini) explosion-induced defensive spray pulsation. Science 2015, 348, 563–567.

- Noirot, C.; Quennedey, A. Fine Structure of Insect Epidermal Glands. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1974, 19, 61–80.

- Noirot, C.; Quennedey, A. Glands, gland cells, glandular units: Some comments on terminology and classification. In Annales De La Societe Entomologique De France; Société entomologique de France: Paris, France, 1991; Volume 27, pp. 123–128.

- Deuve, T. L’abdomen et les genitalia des femelles de Coleopteres Adephaga. Mem. Du Mus. Natl. D’histoire Nat. Paris 1993, 155, 1–184.

More