Developing realistic data sets for evaluating virtual screening methods is a task that has been tackled by the cheminformatics community for many years. Numerous artificially constructed data collections were developed, such as DUD, DUD-E, or DEKOIS. However, they all suffer from multiple drawbacks, one of which is the absence of experimental results confirming the impotence of presumably inactive molecules, leading to possible false negatives in the ligand sets. In light of this problem, the PubChem BioAssay database, an open-access repository providing the bioactivity information of compounds that were already tested on a biological target, is now a recommended source for data set construction. Nevertheless, there exist several issues with the use of such data that need to be properly addressed. In this article, an overview of benchmarking data collections built upon experimental PubChem BioAssay input is provided, along with a thorough discussion of noteworthy issues that one must consider during the design of new ligand sets from this database. The points raised in this review are expected to guide future developments in this regard, in hopes of offering better evaluation tools for novel in silico screening procedures.

- PubChem BioAssay

- benchmarking

- data set

- assay selection

- false positives

- chemical bias

- potency bias

- data curation

Noteworthy Issues with Using Data from PubChem BioAssay for Constructing Benchmarking Data Sets

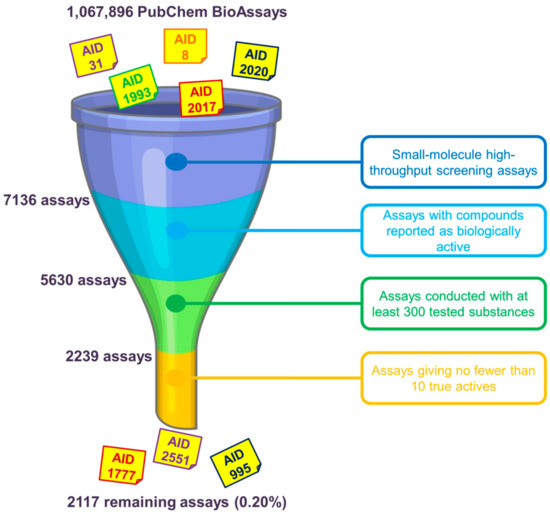

Assay Selection for Evaluating Virtual Screening Methods

Assay Selection as Regards the Data Size and Hit Rates

Assay Selection as Regards the Nature of Virtual Screening

Assay Selection as Regards the Screening Stage

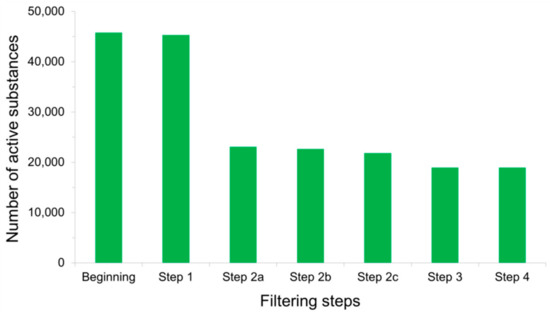

Detecting False Positives among Active Substances

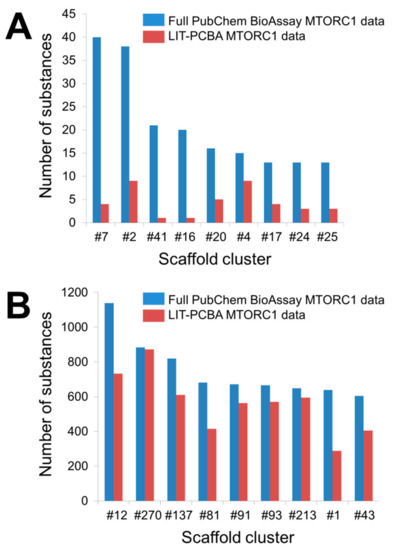

Possible Chemical Bias in Assembling Active and Inactive Substances

| Data Sets | 2D ECFP4 Fingerprint Similarity Search | Molecular Docking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF1% | Number of Retrieved Actives | EF1% | Number of Retrieved Actives | |

| Full PubChem data | 0.6 | 2 | 3.2 | 11 |

| LIT-PCBA MTORC1 data | 0.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 1 |

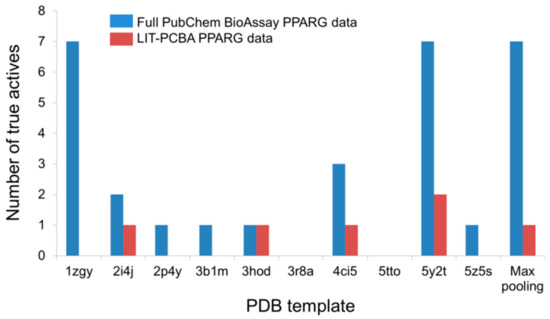

Potency Bias in the Composition of Active Ligand Sets

Processing Input Structures Prior to Virtual Screening

Conclusions

- Rohrer, S.G.; Baumann, K. Maximum unbiased validation (MUV) data sets for virtual screening based on PubChem bioactivity data. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierz, A.C. Virtual screening of bioassay data. J. Cheminformatics 2009, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkiewicz, M.; Lowe, E.W.; Mueller, R.; Mendenhall, J.L.; Teixeira, P.L.; Weaver, C.D.; Meiler, J. Benchmarking ligand-based virtual high-throughput screening with the PubChem database. Molecules 2013, 18, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, M.; Svensson, F.; Schaal, W.; Zhang, J.; Sköld, C.; Brandt, P.; Karlen, A. Toward a benchmarking data set able to evaluate ligand- and structure-based virtual screening using public HTS data. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Holloway, G.A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilberg, E.; Jasial, S.; Stumpfe, D.; Dimova, D.; Bajorath, J. Highly promiscuous small molecules from biological screening assays include many pan-assay interference compounds but also candidates for polypharmacology. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10285–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B. Feeling nature’s PAINS: Natural products, natural product drugs, and pan assay interference compounds (PAINS). J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzi, S.J.; Muratov, E.N.; Tropsha, A. Phantom PAINS: Problems with the utility of alerts for pan-assay INterference CompoundS. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, P.W. Comment on the ecstasy and agony of assay interference compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 2640–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baell, J.B.; Nissink, J.W. Seven year itch: Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) in 2017—Utility and limitations. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nim, S.; Lobato, L.G.; Moreno, A.; Chaptal, V.; Rawal, M.K.; Falson, P.; Prasad, R. Atomic modelling and systematic mutagenesis identify residues in multiple drug binding sites that are essential for drug resistance in the major candida transporter Cdr1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1858, 2858–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.P.; Rees, S.; Kalindjian, S.B.; Philpott, K.L. Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 162, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.H. Accounting artifacts in high-throughput toxicity assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1473, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, A.C.; Oprea, T.I. Optimization of CAMD techniques 3. Virtual screening enrichment studies: A help or hindrance in tool selection? J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2008, 22, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemis, G.W.; Murcko, M.A. The properties of known drugs. 1. Molecular frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 2887–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes, Biovia Corp. Available online: https://www.3dsbiovia.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Schuffenhauer, A.; Ertl, P.; Roggo, S.; Wetzel, S.; Koch, M.A.; Waldmann, H. The scaffold tree, visualization of the scaffold universe by hierarchical scaffold classification. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.N. Surflex-dock 2.1: Robust performance from ligand energetic modeling, ring flexibility, and knowledge-based search. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1988, 28, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, A.; Nourse, J.G.; Hounshell, W.D.; Gushurst, A.K.; Grier, D.L.; Leland, B.A.; Laufer, J. Description of several chemical structure file formats used by computer programs developed at molecular design limited. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1992, 32, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.D.; Gibbs, A.C.; DesJarlais, R.L. Processing of small molecule databases for automated docking. Med. Chem. 2007, 3, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, A.J.; Meegan, M.J.; Carta, G.; Lloyd, D.G. Considerations in compound database preparatio—“hidden” impact on virtual screening results. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45(6), 1908–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellenberger, E.; Rodrigo, J.; Muller, P.; Rognan, D. Comparative evaluation of eight docking tools for docking and virtual screening accuracy. Proteins 2004, 57, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perola, E.; Charifson, P.S. Conformational analysis of drug-like molecules bound to proteins: An extensive study of ligand reorganization upon binding. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 2499–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcou, G.; Rognan, D. Optimizing fragment and scaffold docking by use of molecular interaction fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desaphy, J.; Raimbaud, E.; Ducrot, P.; Rognan, D. Encoding protein-ligand interaction patterns in fingerprints and graphs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polgar, T.; Keserue, G.M. Ensemble docking into flexible active sites. critical evaluation of FlexE against JNK-3 and β-secretase. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, P.C.; Skillman, A.G.; Nicholls, A. Comparison of shape-matching and docking as virtual screening tools. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bietz, S.; Urbaczek, S.; Schulz, B.; Rarey, M. Protoss: A holistic approach to predict tautomers and protonation states in proteinligand complexes. J. Cheminformatics 2014, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molecular Networks Gmbh. Available online: https://www.mn-am.com/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Molecular Operating Environment. Available online: https://www.chemcomp.com/Products.htm (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Sybyl-X Molecular Modeling Software Packages, Version 2.0; TRIPOS Associates, Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2012.

- Daylight Chemical Information Systems. Available online: https://www.daylight.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2020).