Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinone rings are a class of heterocycles present in a wide range of bioactive natural products and analogues thereof. As a direct result of their bioactivity, the synthesis of this privileged class of compounds has been extensively studied. This review provides an overview of these synthetic pathways.

- pyrrole

- pyrazinone

- heterocycle

- natural product

- cycloaddition

- multicomponent reaction

1. Introduction

Nitrogen-containing heteroaromatic rings are valuable motifs in bioactive molecules and recurrent scaffolds present in drugs [1][2]. The application of nitrogen ring systems in drug development is related to their diverse properties, including relatively small conformational freedom, while retaining some polarity, compared to aromatic hydrocarbons. Additionally, commercial availability, synthetic tractability, chemical diversity and the tendency for functionalization should also be highlighted [3]. However, the wide chemical space of nitrogen heterocycles is not yet fully explored in the attempt to find new drug candidates.

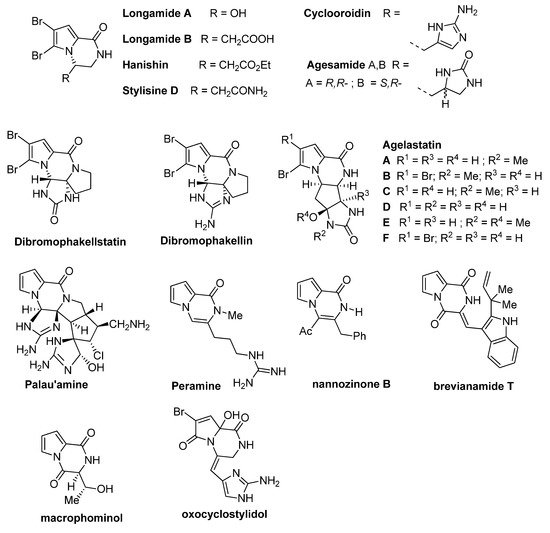

Dihydropyrrolo[1,2-

]pyrazinone rings are found in the structure of a number of bioactive compounds, including synthetic and natural products isolated from various sources like fungi, plants or sponges. These natural products (some structures are shown in

) often contain one or two bromine substituents on the pyrrole ring. The simplest congeners are

[4] and its nonbrominated analog

[5] (not shown),

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9], and

[10]. More complicated tetracyclic analogs include

,

[11] and the different

[12][13]. One of the most complicated pyrrolopyrazinone natural products is

[14], and its structure has been seen as a challenge for total synthesis. Some related natural products are the higher oxidation state analogs

[15] and

[16], containing the pseudoaromatic pyrazinone ring, the pyrrolodiketopiperazines

[17] and

[18], and the oxopyrrole derivative

[19] (

).

Pyrrolopyrazinone natural products.

Several bioactivities have been found for these pyrrolopyrazinone natural products. Hanishin shows cytotoxicity against non-small cell lung carcinoma [7], and agelastatin A and D display significant activity against different cell lines [20]. Longamide B was found to have antiprotozoal [21] and antibacterial [6] properties, with good potency against African trypanosome. Palau’amine and the similar dibromophakellin and dibromophakellstatin inhibit the human 20S proteasome [22]. Peramine is an insect feeding deterrent [23].

2. Fusion of a Pyrazinone to a Pyrrole Derivative

2.1. Starting from 2-Monosubstituted Pyrroles

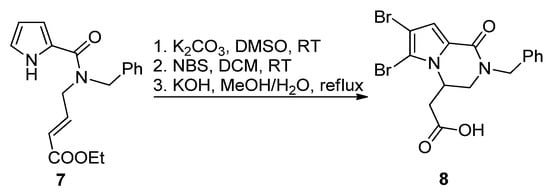

The most common way toward pyrrolopyrazinones is fusing a pyrazinone to a pyrrole. One way to realize this is starting from

-pyrrole-2-carboxamide bearing electrophilic groups on the amide that react in an intramolecular fashion with the nucleophilic pyrrole nitrogen. Several electrophilic groups are possible. Electron-poor alkenes can undergo aza-Michael addition, as in the base-catalyzed formation of

-benzyl longamide B derivative

from the corresponding open chain pyrrole-2-amide

after potassium carbonate (K

CO

)-catalyzed cyclization, bromination with

-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and saponification (

) [24]. A similar aza-Michael cyclization was reported in the total synthesis of longamide B and cyclooroidin via the Wadsworth–Horner–Emmons olefination of longamide A [25][26] or in the 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene(DBU)-catalyzed cyclization of precursors to kinase inhibitors

[27]. An enantioselective aza-Michael cyclization (up to 56%ee) was realized with compounds analogous to

in the presence of a chiral

-benzylammonium phase transfer catalyst derived from quinine [28].

Aza-Michael reaction leading to a longamide B derivative.

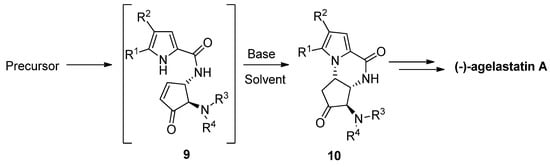

The total synthesis of (-)-agelastatin A involved a similar aza-Michael reaction to an enone intermediate

, which was generated by the oxidation of an allylic alcohol precursor [29] or by a metathesis reaction [30]. Different bases were tried for the cyclization of

to the intermediate

that then could be further elaborated to the natural product. It was found that diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in THF is a suitable base/solvent combination after the acidity of the pyrrole is increased by bromination, whereas nonbrominated pyrrole

resulted in the recovery of the starting material, rearrangement and/or decomposition [29][31][32]. Many variants of this cyclization have been described, with other base/solvent combinations like cesium carbonate in methanol [30] or THF [33] at room temperature, potassium carbonate in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 100 °C [34], trimethylamine in acetonitrile (ACN) at −20 °C [35] and triethylamine (Et

N) in DMSO at room temperature with the in situ generation of enone

by the elimination of a sulfone group [36][37] (

).

Aza Michael reaction as part of (-)-agelastatin total synthesis.

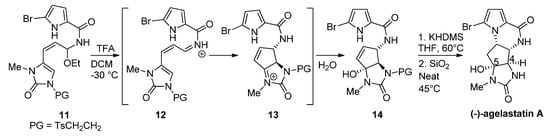

Instead of changing the nucleophilicity of the pyrrole, the electrophilicity of the double bond may be increased by the addition of a Brønsted or Lewis acid. In fact, the biosynthesis of hanishin or longamide B has been described as involving the protonation of a precursor analogous to

by an appropriate enzyme [7]. In a bioinspired total synthesis of

-agelastatin A, a cascade process occurs starting from a hemiaminal

that is converted with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) into a reactive iminium salt

that cyclizes to intermediate

and then undergoes the addition of water to give the hydroxyl derivative

. The deprotection of

and cyclization by heating in the presence of silica (SiO

) at 45 °C affords agelastatin A (68%) and a minor amount (13%) of its 4,5-epimer [38] (

). We can also mention a similar report wherein trifluoroethanol functions as an acidic medium (40 °C) for the diastereoselective cyclization of

to agelastatin A [39].

-cyclooroidin has been prepared in excellent yield (93%), by heating the formic acid salt of the acyclic precursor at 95 °C for 45 h in a sealed tube [40].

Silica-promoted synthesis of (-)-agelastatin A.

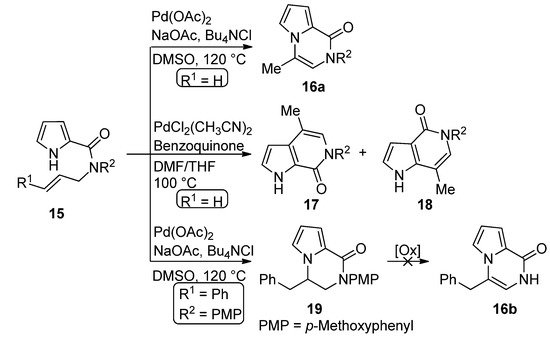

The palladium-catalyzed cyclization of

-allyl pyrrole-2-carboxamide

(R

= H) leads to different products depending on the catalyst. In the presence of palladium acetate (0.1 eq), sodium acetate and tetrabutylammonium chloride (Bu

NCl) in DMSO at 120 °C, the pyrrolo[1,2-

]pyrazine

is formed. On the other hand, PdCl

(CH

CN)

catalyst (0.1 eq.) in a dimethylformamide (DMF)/tetrahydrofuran(THF) mixture at 100 °C, in the presence of a stoichiometric benzoquinone oxidant, gave a 1:1 mixture of the two isomeric [2,3-

] and [3,2-

] fused pyrrolopyridinone derivatives

and

, apparently as the result of cyclization involving the 2-position of the pyrrole followed by rearrangement [41]. Remarkably, when the Pd(OAc)

method was applied to the

-cinnamyl derivative

(R

= Ph), the dihydro derivative

was obtained in modest yield and different oxidants failed to afford the corresponding pyrrolo[1,2-

]pyrazine

[42] (

).

Palladium-catalyzed cyclization of

-allyl pyrrole-2-carboxamide.

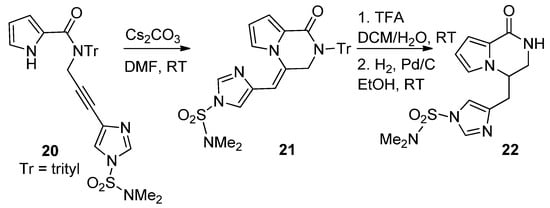

The cyclization reactions of pyrrole nitrogen onto alkyne substituents were studied in basic circumstances. Thus,

-imidazolylpropargyl-substituted pyrrole-2-carboxamide

was favorably converted to the pyrrolopyridazinone

, by an 6-

-dig process, using cesium carbonate (Cs

CO

) in DMF at room temperature. Further deprotection and

-double bond reduction yielded cyclooroidin analog

[43] (

).

Base-catalyzed ring closure of

-propargyl pyrrole-carboxamides.

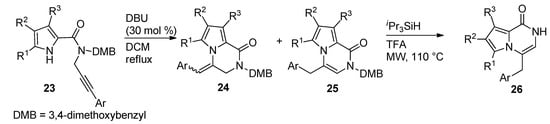

Other examples of the base-catalyzed ring closure of

-propargyl derivatives were reported, with 30 mol% DBU in dichloromethane (DCM) at reflux temperature [44], which led to a mixture of pyrrolopyrazinone isomers

and

with an

double bond and an

double bond, respectively. The isomerization of the

-isomers

to the thermodynamically preferred

-product

and the deprotection mediated by triisopropylsilane (

Pr

SiH) and TFA under microwave (MW) heating, only yielded

(

).

Ring closure of

-(3-arylpropargyl) pyrrole-carboxamides.

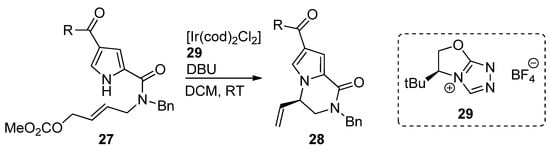

An iridium (I) complex with chiral

-heterocyclic carbene ligand

was used as a catalyst for the intramolecular aminoallylation of acylpyrroles

, leading to (

)-vinyl-substituted pyrrolopyrazinones

[45] in e.e. of 92–95% (

). In a subsequent report, an Ir/phosphoramidite catalytic system was explored to obtain the (

)-isomer, which is used as a starting material for the total synthesis of longamide B, hanishin or cyclooroidin analogs [46].

Iridium-catalyzed intramolecular allylation strategy toward pyrrolopyrazinones.

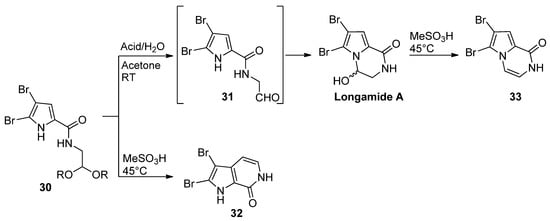

Pyrrole-2-carboxamides

-substituted with an acetal-protected aldehyde function cyclized upon acid-catalyzed deprotection. The outcome of the reaction is dependent on the reaction conditions. The treatment of

with 4-toluenesulfonic acid or HCl in acetone/water at room temperature gave longamide A, probably after the cyclization of the intermediate aldehyde

. Racemic longamide A can be separated into the two enantiomers through chiral chromatography, but these racemize at room temperature within minutes [47]. On the other hand, the isomeric pyrrolopyridine

was formed on the heating of

with methanesulfonic acid (MeSO

H).

was formed on heating with methanesulfonic acid or on treatment with 4-toluenesulfonyl chloride, and trimethylamine gave the dehydrated pyrazinone

[48] (

). Unprotected ketone analogs of

(with different degrees of bromination on the pyrrole ring) were shown to be in equilibrium with the hydroxypyrrolopyrazinones, but the oxidation of the pyrrole ring to a 2-hydroxypyrrolin-5-one with Selectfluor gave the ring-opened product [49].

Alternate intramolecular reactions of acetals and pyrrole.

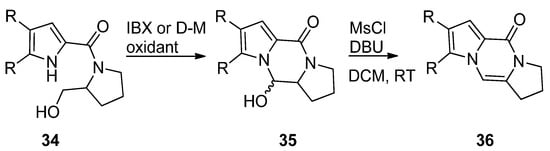

The pyrrole-2-carbamide

(R = H) derived from prolinol on oxidation with 2-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) in DMSO at room temperature [50] or Dess–Martin (D-M) reagent in DCM at room temperature [51] gave the hydroxypyrrolopyrazinone

, which could be dehydrogenated with phosphoryl chloride (POCl

) in pyridine at room temperature [50] or with mesyl chloride and DBU in DCM at room temperature [51] to afford the tricyclic compound

(

). The compounds

and

(R = H, Br) were also obtained in a similar sequence from the reduction of the pyrrolecarboxamide connected to the Weinreb amide of proline with lithiumaluminium hydride [52] or with hydroxyprolinate (diisobutylaluminum hydride reduction) [53], in the framework of total syntheses of dibromophakellstatin.

Cyclization of prolinol derivatives.

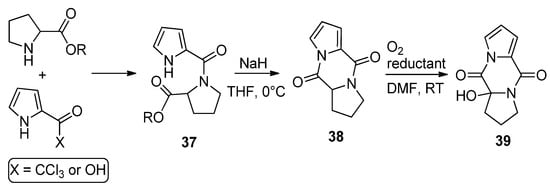

Amides

, resulting from the condensation of 2-trichloroacetylpyrrole (or pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid and amidation reagents) and different amino esters derived from natural amino acids (shown here for proline), were cyclized with sodium hydride in THF to the diketopiperazine derivatives

in high yield. Several reports have appeared in the literature [52][54][55][56][57]. These compounds

could be oxygenated with molecular oxygen to a hydroperoxide and could be reduced in situ with dibutyl sulfide ((

-Bu)

S) or triphenyl phosphine (PPh

), affording the hydroxy product

in high yield [55] (

). Recently, it was found that these diketopiperazines

could function as catalysts in oxygenation reactions [58], and the oxygenation of compound

in the presence of guanidine has also been mentioned as acting in the biogenesis of 2-aminoimidazolidinone metabolites from sponges [54].

Diketopiperazine derivatives from amino esters and pyrrole-2-carboxylic reagents.

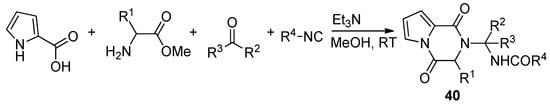

Pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid, carbonyl compounds, isocyanides and amino esters undergo the four-component Ugi reaction to afford the adducts, which cyclized spontaneously at room temperature in methanol and triethylamine (Et

N) to afford a library of polysubstituted pyrrole diketopyrazines 40 [59] (

). An extensive discussion of pyrrolo-fused diketopiperazines is out of the scope of this review. Instead, we give a few additional key references [50][58][60][61][62][63].

Pyrrolopyrazinones by Ugi four component reaction.

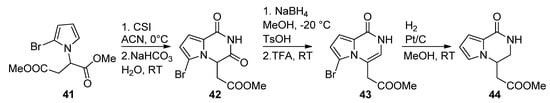

2.2. Starting from 1-Monosubstituted Pyrroles

There are few examples in the literature of a 1-monosubstitued pyrrole that is converted to a pyrrolopyrazinone. Thus, the pyrrole

was prepared from aspartic acid dimethyl ester and reacted with chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (CSI), affording the pyrrolopyrazinedione

. Reduction with sodium borohydride in methanol, and dehydration, gave the pyrazinone

, which was then reduced with Pt/C and H

, simultaneously removing the bromine, to longamide B analogs

[64] (

). Compounds analogous to

have also been prepared from the 2-trichloracetylation of

followed by substitution with primary amines [20][63].

Cyclization of 1-monosubstituted pyrrole with CSI.

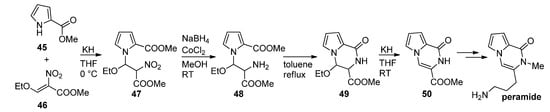

2.3. Starting from 1,2-Disubstituted Pyrroles

There are a number of reports wherein a 1,2-disubstituted pyrrole was used as a starting material for the formation of a pyrrolopyrazinone. This may be done with (1) a single acyclic precursor containing an electrophilic carbonyl group at the 2-position and a nucleophilic substituent (mostly amine) at the 1-position, or (2) vice versa, or (3) the condensation of two components of which one contains the disubstituted pyrrole.

Thus, methyl 2-pyrrolecarboxylate

was combined with a nitroalkene

in the presence of potassium hydroxide to give a nitroalkyl-substituted pyrrole

, which was then reduced with sodium borohydride (NaBH

)/cobalt(II)chloride (CoCl

), and the amine

cyclized at reflux temperature in toluene after which ethanol was eliminated from

in basic medium, leading to the product

that was used as a starting material for the first total synthesis of peramide [23][65] (

). As an alternative to a nitro compound, a

-CH

CN functionality can be introduced, using iodoacetonitrile, which can be reduced to the amine, which then further cyclizes to a pyrrolopyrazinone [66].

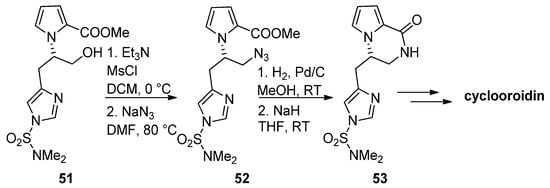

First total synthesis of peramide.

The azide function is a common precursor for amine that can easily be generated in situ by catalytic reduction. Therefore, in the framework of a total synthesis of cyclooroidin, alcohol

was mesylated and converted into azide

, and catalytic hydrogenation followed by the addition of sodium hydride (NaH) resulted in the formation of the pyrrolopyrazinone

, which was then further elaborated to cyclooroidin [67] (

). Similar strategies have been used in the total synthesis of (-)-hanishin [68] or in the synthesis of histone deacetylase inhibitors [69] and the inhibitors of the mycobacterium ATP synthase [70].

Azides as intermediates in the total synthesis of cyclooroidin.

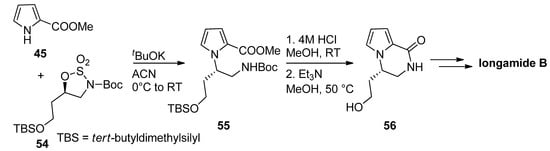

Typical amine-protecting groups like

-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) and fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) can also be used in intermediates leading to pyrrolopyrazinones. Thus, the condensation of methyl 2-pyrrolocarboxylate

with cyclic sulfamidates

and the potassium

-butoxide base gave the precursor

, which was deprotected with acid and then cyclized, mediated by triethylamine (Et

N) [71]. The resulting pyrrolopyrazinone

can then be further elaborated to longamide B or hanishin [72][71][73] (

). Further examples of this strategy have been reported toward longamide B derivative, kinase inhibitors [74] and mGluR1 antagonists [66], and we can also mention a Fmoc-based total synthesis of cyclooroidin [75].

Boc-strategy toward longamide B derivatives.

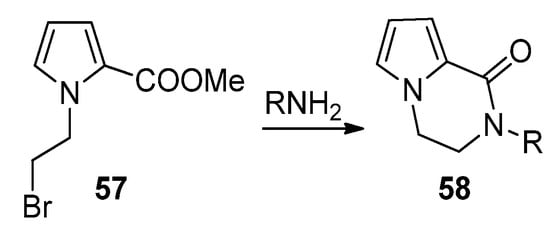

An effective example of a two-component reaction leading to the pyrrolopyrazinone scaffold is the reaction of

-(2-bromoethyl)pyrrole-2-carboxylates

with amines, leading to the

-substituted bicyclic derivatives

(

). Probably the reaction starts with the substitution of the bromine by the amine, followed by lactamization. Several examples were reported [76][66][77]. In the framework of agelastatin total synthesis, some examples were reported where, in the presence of sodium hydride, an amide substituted a bromine at the side chain connected to nitrogen, proving that the opposite order of reactions is also possible [78][79].

Bromine substitution and lactamization with primary amines.

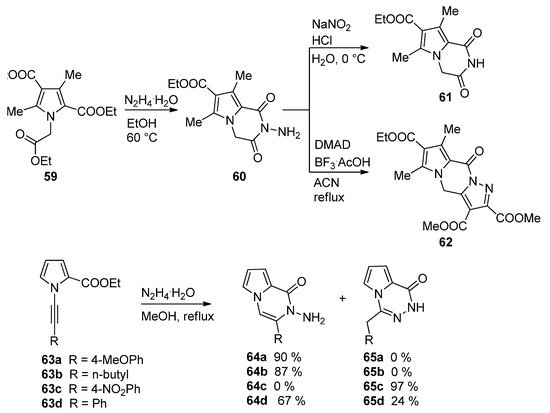

The condensation of hydrazine in ethanol with the triester

led to the

-aminopyrrolopyrazinone

, which, upon treatment with sodium nitrite and acid, gave the deaminated derivative

, and the condensation of

with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD) catalyzed by BF

/acetic acid (BF

·AcOH) complex in acetonitrile afforded the interesting pyrazolo-fused analog

[80]. A related cyclization of 1-alkynylpyrrole-2-carboxylate

and hydrazine hydrate occurred with remarkable selectivity. Electron-rich aryl groups or alkyl groups R give the pyrrolopyrazinone

, whereas for R = 4-nitrophenyl, only the 1,2,4-triazine

is obtained. The phenyl substituted analogs

gave a mixture of the two products

and

[81] (

).

Reactions of biselectrophilic pyrroles with hydrazine.

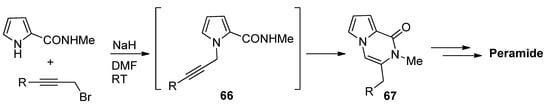

-Propargylpyrrole-2-carboxamides

prepared in situ were cyclized to pyrrolopyrazinones

using NaH in DMF at room temperature [82], which was applied to a total synthesis of peramide [83] (

).

propargylpyrrole-2-carboxamide synthesis and cyclization.

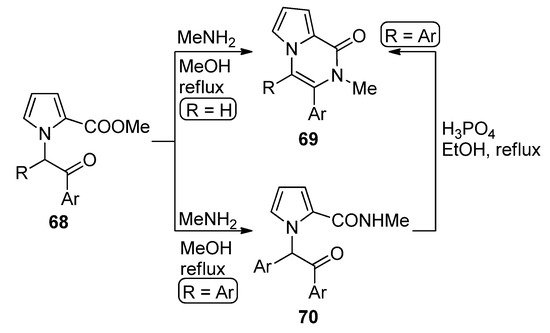

-(phenacyl)substituted pyrrole-2-carboxylates

(R = H) reacted with methylamine (MeNH

) in methanol at reflux to give direct access to pyrrolopyrazinones

. The diaryl-substituted analogs

(R = Ar), on the other hand, gave the amidation product

, which could be converted to the diaryl analog of

(R = Ar) by heating

at reflux in a 85% phosphoric acid/ethanol mixture [84] (

). An early study of the synthesis of analogs of

involved the condensation of amines with intermediate pyrrolo-1,4-oxazines (derived from the

-alkylation of 2-(trichloroacetyl)pyrrole with chloroacetone) [85]. When acetal-protected 1-acetaldehyde 2-carboxamidepyrrole is deprotected in reflux acetic acid, the unsubstituted derivative of pyrrolopyrazinone analog of

was obtained [86].

Cyclization of

-phenacylpyrroles and methylamine.

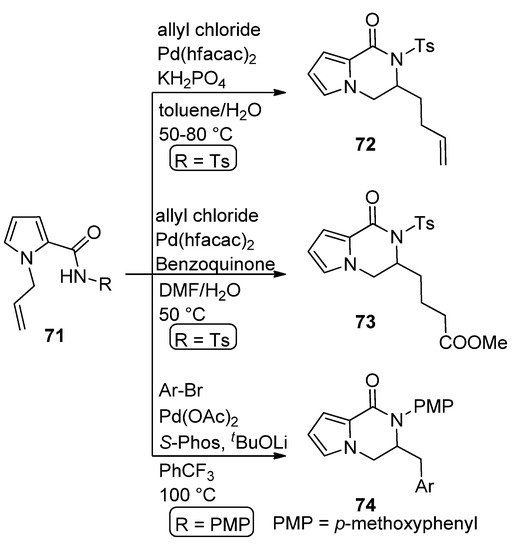

The carboamination of

-allyl pyrrole carboxamide

(R = Ts) with allyl chloride in the presence of 10 mol% Pd(II) hexafluoroacetoacetate (Pd(hfacac)

) and potassium dihydrogenphosphate in toluene/water at 50–80 °C leads to dihydropyrrolopyrazinone

[87]. A similar reaction carried out with the same catalyst in the presence of benzoquinone in DMF/water gave the oxygenated analog

[88]. Similarly, the carboamination of

(R =

-methoxyphenyl, PMP) with aryl bromides in the presence of Pd(OAc)

/

-Phos catalyst at 100 °C afforded the dihydropyrrolopyrazinone

[89] (

).

Pd(II)-catalyzed carboamination reactions.

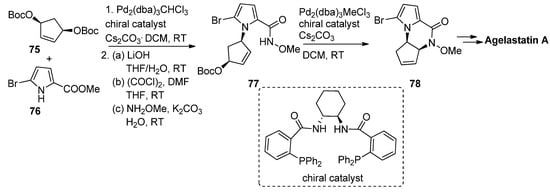

Allylpalladium species can function as electrophiles in cyclization reactions leading to pyrrolopyrazinones, and this has mainly been used in the context of the total synthesis of natural products. Thus, an enantioselective synthesis of agelastatin A reported by Trost et al. involved firstly the palladium-catalyzed allylation starting from the prochiral bisprotected cyclopentenediol

with 5-bromopyrrolecarboxylate

in the presence of a chelating chiral bisphosphine catalyst, affording the precursor that then, after conversion to the

-methoxyamide

, underwent a second intramolecular allylation to afford pyrrolopyrazinone

, which could then be further elaborated to agelastatin A [90] (

). Many variants on this allylation strategy, mostly as a part of agelastatin natural product total syntheses, were reported [91][92][93][94][95][96].

Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular allylation strategy toward pyrrolopyrazinone.

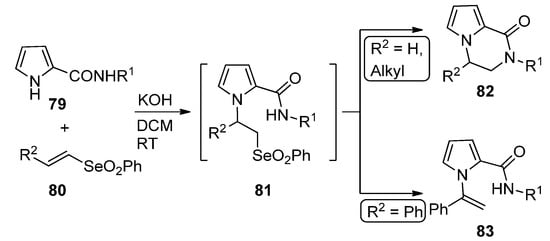

A remarkable domino reaction of pyrrole-2-carboxamides

and vinyl selenones

(R

= H, alkyl) in basic medium occurs via an initial Michael addition, followed by the intramolecular substitution of intermediate

, leading to pyrrolopyrazinone

. In the case of styryl selenone

(R

= Ph), the

-(1-phenylethenyl)pyrrole

is formed instead [97] (

).

Domino reaction of pyrrole-2-carboxamides and vinyl selenones.

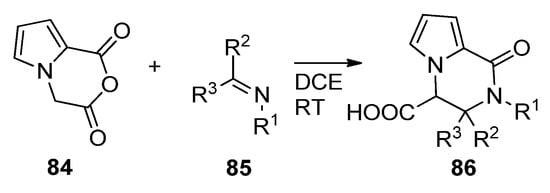

The Castagnoli–Cushman reaction (CCR) is a ring opening/ring closure reaction of cyclic anhydrides with imines. When applied to anhydride

, prepared from the diacid with trifluoroacetic anhydride, condensation with different imines

in 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) at room temperature led to a large variety of trisubstituted pyrrolopyrazinones

[98] (

). The reaction has also been applied to substituted pyrrole anhydrides

[99].

Castagnoli–Cushman reaction of pyrrole cyclic anhydrides.

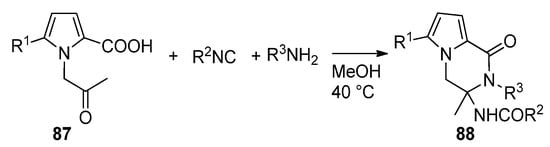

The multicomponent Ugi reaction has been applied to

-(2-oxopropyl)pyrrole-2-carboxylic acids

. In this case, two of the four components (the acid and the ketone) of the Ugi reaction are present on the pyrrole moiety, and two more are added under the form of an isonitrile and an amine. This leads to a library of polysubstituted pyrrolopyrazinones

[100] (

). Compounds of this type have been described as dengue inhibitors [101].

Ugi reaction toward pyrrolopyrazinones.

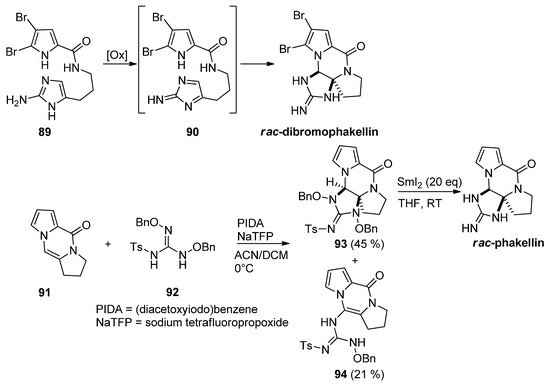

Different approaches to

-dibromophakellin or other tetracyclic marine natural products rely on the intramolecular cycloaddition of a reactive intermediate

generated after the oxidation of aminoimidazole

. This chemistry has been reviewed before [102]. Recently, an intermolecular variant has been described starting from tricyclic

, which was reacted with guanidine derivative

after oxidation with (diacetoxyiodo)benzene (PIDA) and sodium tetrafluoropropoxide (NaTFP) base. Fair amounts of cycloadduct

were obtained together with a minor amount of open chain compound

. The reduction of

with an excess of SmI

then gave the

-phakellin [103] (

). Other approaches involving regio- and stereoselective additions of nitrogen species to analogs of

have been mentioned in the framework of dibromophakellstatin total syntheses [51][102][104][105][106].

Oxidative additions of aminoimidazoles and guanidine derivatives toward phakellin natural products.

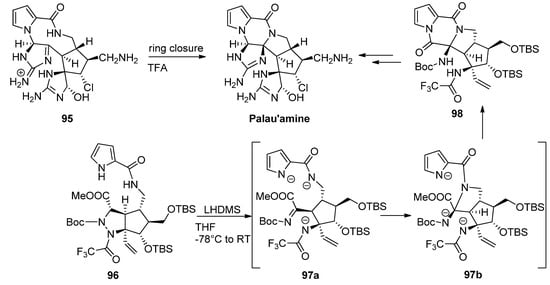

Different strategies for the total synthesis of palau’amine have been reported, and an exhaustive discussion is beyond the scope of this text, so the reader is referred to some dedicated reviews [107]. One of methods that stand out is the ring contraction of the macrocycle

reported by Baran as the final step toward palau’amine [108]. One other remarkable process is a cascade reaction of precursor

with the initial deprotonation and ring opening of the tetrahydropyrazole toward intermediate

followed by formation or the pyrrolidine ring of intermediate

and subsequent formation of the diketopiperazine

, which then was further elaborated to palau’amine [109] (

).

Different cyclization strategies to palau’amine.

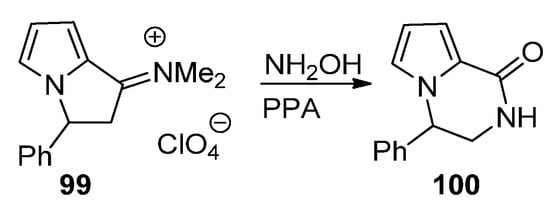

A final strategy toward pyrrolopyrazinones starting from pyrrole building blocks is through the ring expansion of pyrrolizidine derivatives, using the Beckmann rearrangement of the phenyl derivative

, and, after condensation with hydroxylamine and heating in polyphosphoric acid (PPA), the pyrrolopyrazine

is obtained [110] (

).

Ring expansion of pyrrolizidine to pyrrolopyrazinone.

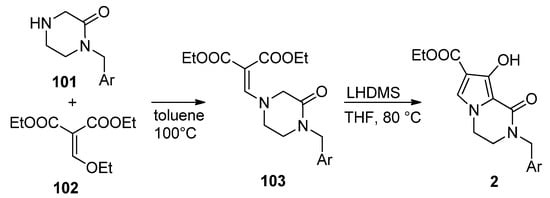

2.4. Fusion of a Pyrrole to a Pyrazinone Derivative

This approach has been much less studied than the pyrrole-first method, with only a few reports so far. Thus, the integrase inhibitors

were obtained, starting from pyrazinone

and diethyl ethoxymethylene malonate

, by heating at 100 °C in toluene. The resulting enamine

was then cyclized with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide LHMDS at 80 °C in THF, affording compound

[111] (

).

Synthesis of hydroxy-substituted pyrrolopyrazinones.

An efficient two step synthesis of polysubstituted pyrrolopyrazinones started with the Vilsmeier–Haack chloroformylation of readily available ketones

to afford biselectrophilic 2-chloroacrolein intermediate

, which was then condensed with pyrazinones

in the presence of

-methylmorpholine (NMM) base in DMF at 115 °C, affording compounds

in fair yields, in some case accompanied with the isomer

[112] (

).

Two-step synthesis of pyrrolopyrazinones from 2-chloroacroleins.

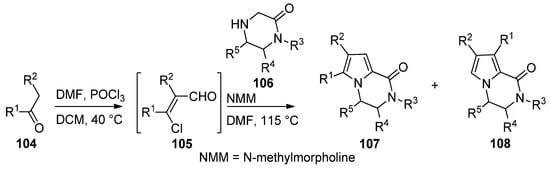

Isoxazolino-fused piperazinones

were prepared via the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of nitrones

, which was in equilibrium with the open chain oximes

, to dimethyl acetylene dicarboxylate (DMAD). Remarkably, upon heating a rearrangement occurs to pyrrolopyrazinones

, presumably via a multistep ring contraction/ring expansion mechanism [113] (

).

Synthesis and rearrangement of isoxazolinopyrazinones.

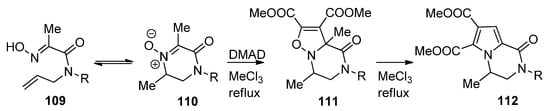

Diketopiperazines

underwent base-catalyzed aldol condensations with different aldehydes, affording adducts that, in the case of acetal substituents, as for

, underwent camphorsulfonic acid (CSA)-mediated cyclization on heating in toluene to pyrrolodiketopiperazines

. The aldol condensation products

resulting from alkynyl aldehydes underwent gold-catalyzed cyclization under similar conditions, giving an alternative preparation for compounds

with a larger scope of R

-substituents [114] (

).

Brønsted and Lewis acid-catalyzed cyclization reactions of diketopiperazines.

2.5. Multicomponent Reactions

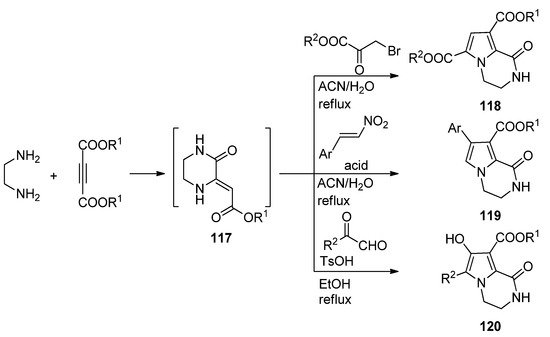

A three-component reaction of 1,2-diaminoethane, dialkyl acetylene dicarboxylate and different biselectrophiles present a very straightforward way to pyrrolopyrazinones. Probably the diamine first reacts with the electrophilic acetylene, and the intermediate pyrazinone derivative

then cyclizes with the biselectrophile. Thus, reaction with bromopyruvate in acetonitrile or water at reflux resulted in diester

[115][116]. On the other hand, reactions with nitrostyrene, catalyzed by sulfamic acid (SA) in acetonitrile [117] or Fe

O

@SiO

-OSO

H magnetic nanoparticles in water [33] afforded aryl derivatives

, and condensation with methyl- or arylglyoxal in ethanol at reflux with

-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH) catalysis gave hydroxyl derivatives

[118] (

).

Three-component reactions leading to dihydropyrrolopyrazinones.

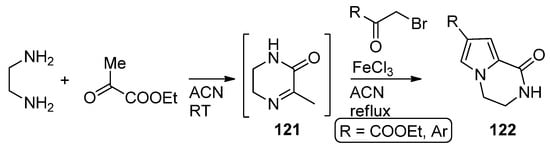

In a variant of this three component reaction, 1,2-diaminoethane and ethyl pyruvate are combined at room temperature in acetonitrile, and then

-bromo ketones are added and the mixture heated in the presence of iron (III) chloride to afford

via the reaction of intermediate pyrazine

with the bromoketone [119] (

).

Three-component reaction with ethyl pyruvate.

2.6. Miscellaneous

The ABDE core of palau’amine was constructed from the dibromide salt of diamine

and triscarbonyl compound

by a cascade reaction involving a Paal–Knorr pyrrole synthesis, leading to intermediate pyrrole

, which, after neutralization, undergoes subsequent lactamization to afford tetracyclic

[120] (

).

Cascade process to the ABDE core of palau’amine.

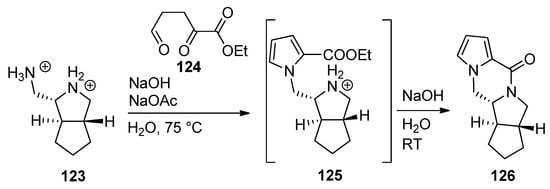

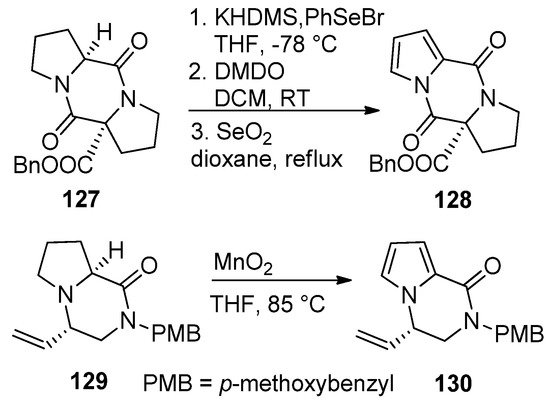

Pyrrolidino-fused diketopiperazines

could be oxidized to the pyrrolodiketopiperazines

after sequential deprotonation, phenylselenation, oxidation with dimethyldioxirane (DMDO)/elimination and aromatization of the intermediate pyrroline by heating with selenium dioxide in dioxane. Earlier attempts to aromatize

with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) gave a lower yield (20–30%) and was accompanied by difficult purification [104]. Recently, the proline-derived compound

was oxidized to the pyrrole

with MnO

in THF at 85 °C without effecting the vinyl or dihydropyrazinone parts [121] (

).

Aromatization of pyrrolidino-fused diketopiperazines and pyrazinones.

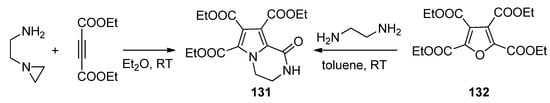

The condensation of

-(2-aminoethyl)aziridine with two equivalents of diethyl acetylenedicarboxylate gave the triester

, the same compound that could be obtained through the ring transformation of the furan tetraester

and 1,2-diaminoethane [122] (

).

Formation of pyrrolopyrazinone triesters.

References

- Taylor, A.R.D.; Maccoss, M.; Lawson, A.D.G. Supporting Information Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859.

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274.

- Ritchie, T.J.; Macdonald, S.J.; Young, R.J.; Pickett, S.D. The impact of aromatic ring count on compound developability: Further insights by examining carbo- and hetero-aromatic and -aliphatic ring types. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 164–171.

- Cafieri, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Mangoni, A.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Longamide and 3,7-dimethylisoguanine, two novel alkaloids from the marine sponge Agelas longissima. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 7893–7896.

- Uemoto, H.; Tsuda, M.; Kobayashi, J. Mukanadins A−C, New Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from Marine SpongeAgelasnakamurai. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1581–1583.

- Cafieri, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Novel Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from the SpongeAgelas dispar. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 122–125.

- Mancini, I.; Guella, G.; Amade, P.; Roussakis, C.; Pietra, F. Hanishin, a Semiracemic, Bioactive C9 Alkaloid of the Axinellid Sponge Acanthella carteri from the Hanish Islands. A Shunt Metabolite? Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 6271–6274.

- Sun, J.; Wu, J.; An, B.; De Voogd, N.J.; Cheng, W.; Lin, W. Bromopyrrole Alkaloids with the Inhibitory Effects against the Biofilm Formation of Gram Negative Bacteria. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 9.

- Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Two novel pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids from the Mediterranean sponge Agelas oroides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 9917–9922.

- Tsuda, M.; Yasuda, T.; Fukushi, E.; Kawabata, J.; Sekiguchi, M.; Fromont, J.; Kobayashi, J. Agesamides A and B, Bromopyrrole Alkaloids from SpongeAgelasSpecies: Application of DOSY for Chemical Screening of New Metabolites. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4235–4238.

- Pettit, G.R.; McNulty, J.; Herald, D.L.; Doubek, D.L.; Chapuis, J.-C.; Schmidt, J.M.; Tackett, L.P.; Boyd, M.R. Antineoplastic Agents. 362. Isolation and X-ray Crystal Structure of Dibromophakellstatin from the Indian Ocean SpongePhakellia mauritiana1. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 180–183.

- D’Ambrosio, M.; Guerriero, A.; Ribes, O.; Pusset, J.; Leroy, S.; Pietra, F. Agelastatin a, a new skeleton cytotoxic alkaloid of the oroidin family. Isolation from the axinellid sponge Agelas dendromorpha of the coral sea. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1993, 1305–1306.

- Hong, T.W.; Jímenez, D.R.; Molinski, T.F. Agelastatins C and D, New Pentacyclic Bromopyrroles from the SpongeCymbastelasp., and Potent Arthropod Toxicity of (−)-Agelastatin A. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 158–161.

- Kinnel, R.B.; Gehrken, H.P.; Scheuer, P.J. Palau’amine: A cytotoxic and immunosuppressive hexacyclic bisguanidine antibiotic from the sponge Stylotella agminata. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3376–3377.

- Rowan, D.; Hunt, M.B.; Gaynor, D.L. Peramine, a novel insect feeding deterrent from ryegrass infected with the endophyte Acremonium loliae. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986, 935–936.

- Jansen, R.; Sood, S.; Mohr, K.I.; Kunze, B.; Irschik, H.; Stadler, M.; Müller, R. Nannozinones and Sorazinones, Unprecedented Pyrazinones from Myxobacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2545–2552.

- Song, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, H.; Ren, B.; Chen, C.; Piggott, A.; Yu, K.; Gao, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; et al. Brevianamides with Antitubercular Potential from a Marine-Derived Isolate of Aspergillus versicolor. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4770–4773.

- Trigos, A. Macrophominol, a diketopiperazine from cultures of Macrophomina phaseolina. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1697–1698.

- Grube, A.; Köck, M. Oxocyclostylidol, an Intramolecular Cyclized Oroidin Derivative from the Marine Sponge Stylissacaribica§. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1212–1214.

- Han, S.; Siegel, D.S.; Morrison, K.C.; Hergenrother, P.J.; Movassaghi, M. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of All Known (−)-Agelastatin Alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 11970–11984.

- Scala, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Menna, M.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Tierney, M.; Kaiser, M.; Tasdemir, D. Bromopyrrole Alkaloids as Lead Compounds against Protozoan Parasites. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2162–2174.

- Lansdell, T.A.; Hewlett, N.M.; Skoumbourdis, A.P.; Fodor, M.D.; Seiple, I.B.; Su, S.; Baran, P.S.; Feldman, K.S.; Tepe, J.J. Palau’amine and Related Oroidin Alkaloids Dibromophakellin and Dibromophakellstatin Inhibit the Human 20S Proteasome. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 980–985.

- Brimble, M.A.; Rowanb, D.D. Synthesis of peramine, an insect feeding deterrent mycotoxin from Acremonium lolii. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1988, 4, 978–979.

- Bandini, M.; Eichholzer, A.; Monari, M.; Piccinelli, F.; Umani-Ronchi, A. Versatile Base-Catalyzed Route to Polycyclic Heteroaromatic Compounds by Intramolecular Aza-Michael Addition. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 2917–2920.

- Banwell, M.G.; Bray, A.M.; Willis, A.C.; Wong, D.J. First syntheses of the pyrroloketopiperazine marine natural products (±)-longamide, (±)-longamide B, (±)-longamide B methyl ester and (±)-hanishin. New J. Chem. 1999, 23, 687–690.

- Papeo, G.; Frau, M.A.G.-Z.; Borghi, D.; Varasi, M. Total synthesis of (±)-cyclooroidin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 8635–8638.

- Casuscelli, F.; Ardini, E.; Avanzi, N.; Casale, E.; Cervi, G.; D’Anello, M.; Donati, D.; Faiardi, D.; Ferguson, R.D.; Fogliatto, G.; et al. Discovery and optimization of pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinones leads to novel and selective inhibitors of PIM kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 7364–7380.

- Bandini, M.; Bottoni, A.; Eichholzer, A.; Miscione, G.P.; Stenta, M. Asymmetric Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed Intramolecular N-Alkylation of Indoles and Pyrroles: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12462–12473.

- Ichikawa, Y.; Yamaoka, T.; Nakano, A.K.; Kotsuki, H. Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A by [3.3] Sigmatropic Rearrangement of Allyl Cyanate. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2989–2992.

- Davis, F.A.; Deng, J. Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A Using Sulfinimine (N-Sulfinyl Imine) Derived Methodologies. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 621–623.

- Domostoj, M.M.; Irving, E.; Scheinmann, F.; Hale, K.J. New Total Synthesis of the Marine Antitumor Alkaloid (−)-Agelastatin A. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2615–2618.

- Kano, T.; Sakamoto, R.; Akakura, M.; Maruoka, K. Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Vicinal Diamines by Organocatalytic Asymmetric Mannich Reaction of N-Protected Aminoacetaldehydes: Formal Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7516–7520.

- Tsuchimochi, I.; Kitamura, Y.; Aoyama, H.; Akai, S.; Nakai, K.; Yoshimitsu, T. Total synthesis of (−)-agelastatin A: An SH2′ radical azidation strategy. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9893–9896.

- Dickson, D.P.; Wardrop, D.J. Total Synthesis of (±)-Agelastatin A, A Potent Inhibitor of Osteopontin-Mediated Neoplastic Transformations. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1341–1344.

- Hama, N.; Matsuda, T.; Sato, T.; Chida, N. Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A: The Application of a Sequential Sigmatropic Rearrangement. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2687–2690.

- Feldman, K.S.; Saunders, J.C. Alkynyliodonium Salts in Organic Synthesis. Application to the Total Synthesis of (−)-Agelastatin A and (−)-Agelastatin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9060–9061.

- Feldman, K.S.; Saunders, J.C.; Wrobleski, M.L. Alkynyliodonium Salts in Organic Synthesis. Development of a Unified Strategy for the Syntheses of (−)-Agelastatin A and (−)-Agelastatin B. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7096–7109.

- Reyes, J.C.P.; Romo, D. Bioinspired Total Synthesis of Agelastatin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6870–6873.

- Duspara, P.A.; Batey, R.A. A Short Total Synthesis of the Marine Sponge Pyrrole-2-aminoimidazole Alkaloid (±)-Agelastatin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10862–10866.

- Pöverlein, C.; Breckle, G.; Lindel, T. Diels−Alder Reactions of Oroidin and Model Compounds. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 819–821.

- Beccalli, E.M.; Broggini, G.; Martinelli, M.; Paladino, G.; Maria, B.E. Pd-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization of pyrrolo-2-carboxamides: Regiodivergent routes to pyrrolo-pyrazines and pyrrolo-pyridines. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1077–1082.

- Llauger, L.; Bergami, C.; Kinzel, O.D.; Lillini, S.; Pescatore, G.; Torrisi, C.; Jones, P. A novel base-mediated intramolecular hydroamination to build fused heteroaryl pyrazinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 172–177.

- Bhandari, M.R.; Yousufuddin, M.; Lovely, C.J. Diversity-Oriented Approach to Pyrrole-Imidazole Alkaloid Frameworks. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1382–1385.

- Pescatore, G.; Branca, D.; Fiore, F.; Kinzel, O.; Bufi, L.L.; Muraglia, E.; Orvieto, F.; Rowley, M.; Toniatti, C.; Torrisi, C.; et al. Identification and SAR of novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2H)-one derivatives as inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1094–1099.

- Ye, K.-Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zhuo, C.-X.; Dai, L.-X.; You, S. An Iridium(I) N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complex Catalyzes Asymmetric Intramolecular Allylic Amination Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8113–8116.

- Zhuo, C.-X.; Zhang, X.; You, S.-L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrrole-Fused Piperazine and Piperazinone Derivatives via Ir-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Amination. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5307–5310.

- Marchais, S.; Al Mourabit, A.; Ahond, A.; Poupat, C.; Potier, P. Synthesis of the marine carbinolamine (+/−) longamide control of N-1 and C-3 bromopyrrole nucleophilicity. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5519–5522.

- Sosa, A.C.B.; Yakushijin, K.; Horne, D.A. Controlling cyclizations of 2-pyrrolecarboxamidoacetals. Facile solvation of β-amido aldehydes and revised structure of synthetic homolongamide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 4295–4299.

- Allmann, T.C.; Moldovan, R.-P.; Jones, P.G.; Lindel, T. Synthesis of Hydroxypyrrolone Carboxamides Employing Selectfluor. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 22, 111–115.

- Jacquot, D.E.; Hoffmann, H.; Polborn, K.; Lindel, T. Synthesis of the dipyrrolopyrazinone core of dibromophakellstatin and related marine alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3699–3702.

- Chung, R.; Yu, E.; Incarvito, C.D.; Austin, D.J. Hypervalent Iodine-Mediated Vicinal Syn Diazidation: Application to the Total Synthesis of (±)-Dibromophakellstatin. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3881–3884.

- Travert, N.; Martin, M.-T.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.-L.; Al-Mourabit, A. Regioselective intramolecular N1–C3 cyclizations on pyrrole–proline to ABC tricycles of dibromophakellin and ugibohlin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 249–252.

- Lindel, T.; Zöllinger, M.; Mayer, P. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (-)-Dibromophakellstatin. Synlett 2007, 2007, 2756–2758.

- Travert, N.; Al-Mourabit, A. A Likely Biogenetic Gateway Linking 2-Aminoimidazolinone Metabolites of Sponges to Proline: Spontaneous Oxidative Conversion of the Pyrrole-Proline-Guanidine Pseudo-peptide to Dispacamide A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10252–10253.

- Tian, H.; Ermolenko, L.; Gabant, M.; Vergne, C.; Moriou, C.; Retailleau, P.; Al-Mourabit, A. Pyrrole-Assisted and Easy Oxidation of Cyclic α-Amino Acid- Derived Diketopiperazines under Mild Conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1525–1533.

- Ermolenko, L.; Zhaoyu, H.; Lejeune, C.; Vergne, C.; Ratinaud, C.; Nguyen, T.B.; Al-Mourabit, A. Concise synthesis of Didebromohamacanthin A and Demethylaplysinopsine: Addition of Ethylenediamine and Guanidine Derivatives to the Pyrrole-Amino Acid Diketopiperazines in Oxidative Conditions. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 872–875.

- Nelli, M.R.; Scheerer, J.R. Synthesis of Peramine, an Anti-insect Defensive Alkaloid Produced by Endophytic Fungi of Cool Season Grasses. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1189–1192.

- Petsi, M.; Zografos, A.L. 2,5-Diketopiperazine Catalysts as Activators of Dioxygen in Oxidative Processes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7093–7099.

- Pandey, S.; Khan, S.; Singh, A.; Gauniyal, H.M.; Kumar, B.; Chauhan, P.M.S. Access to Indole- And Pyrrole-Fused Diketopiperazines via Tandem Ugi-4CR/Intramolecular Cyclization and Its Regioselective Ring-Opening by Intermolecular Transamidation. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10211–10227.

- Imaoka, T.; Akimoto, T.; Iwamoto, O.; Nagasawa, K. Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellin and (+)-Dibromophakellstatin. Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 1810–1816.

- Imaoka, T.; Iwamoto, O.; Nagasawa, K.; Noguchi, K.-I. Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3799–3801.

- Adams, L.A.; Valente, M.W.; Williams, R.M. A concise synthesis of d,l-brevianamide B via a biomimetically-inspired IMDA construction. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 5195–5200.

- Negoro, T.; Murata, M.; Ueda, S.; Fujitani, B.; Ono, Y.; Kuromiya, A.; Komiya, M.; Suzuki, K.; Matsumoto, J.-I. Novel, Highly Potent Aldose Reductase Inhibitors: (R)-(−)-2-(4-Bromo-2-fluorobenzyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine- 4-spiro-3‘-pyrrolidine-1,2‘,3,5‘-tetrone (AS-3201) and Its Congeners. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 4118–4129.

- Zhao, D.-G.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Peng, W.; Zhou, A.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Du, Z.; Zhang, K. Total synthesis and cytotoxic activities of longamide B, longamide B methyl ester, hanishin, and their analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 6–8.

- Brimble, M.A.; Rowan, D.D. Synthesis of the insect feeding deterrent peramine via Michael addition of a pyrrole anion to a nitroalkene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1990, 1, 311–314.

- Micheli, F.; Cavanni, P.; Di Fabio, R.; Marchioro, C.; Donati, D.; Faedo, S.; Maffeis, M.; Sabbatini, F.M.; Tranquillini, M.E. From pyrroles to pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinones: A new class of mGluR1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1342–1345.

- Mukherjee, S.; Sivappa, R.; Yousufuddin, M.; Lovely, C.J. Asymmetric Total Synthesis ofent-Cyclooroidin. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4940–4943.

- Das Adhikary, N.; Kwon, S.; Chung, W.-J.; Koo, S. One-Pot Conversion of Carbohydrates into Pyrrole-2-carbaldehydes as Sustainable Platform Chemicals. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7693–7701.

- Blackburn, C.; Barrett, C.; Brunson, M.; Chin, J.; England, D.; Garcia, K.; Gigstad, K.; Gould, A.; Gutiérrez, J.; Hoar, K.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors derived from 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine and related heterocycles selective for the HDAC6 isoform. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5450–5454.

- Surase, Y.B.; Samby, K.; Amale, S.R.; Sood, R.; Purnapatre, K.P.; Pareek, P.K.; Das, B.; Nanda, K.; Kumar, S.; Verma, A.K. Identification and synthesis of novel inhibitors of mycobacterium ATP synthase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3454–3459.

- Fukase, K.; Fujimoto, Y.; Shiokawa, Z.; Inuki, S. Efficient Synthesis of (–)-Hanishin, (–)-Longamide B, and (–)-Longamide B Methyl Ester through Piperazinone Formation from 1,2-Cyclic Sulfamidates. Synlett 2015, 27, 616–620.

- Shiokawa, Z.; Kashiwabara, E.; Yoshidome, D.; Fukase, K.; Inuki, S.; Fujimoto, Y. Discovery of a Novel Scaffold as an Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) Inhibitor Based on the Pyrrolopiperazinone Alkaloid, Longamide B. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 2682–2689.

- Cheng, G.; Wang, X.; Bao, H.; Cheng, C.; Liu, N.; Hu, Y. Total Syntheses of (−)-Hanishin, (−)-Longmide B, and (−)-Longmide B Methyl Ester via a Novel Preparation of N-Substituted Pyrrole-2-Carboxylates. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1062–1065.

- Ward, R.A.; Bethel, P.; Cook, C.; Davies, E.; Debreczeni, J.E.; Fairley, G.; Feron, L.; Flemington, V.; Graham, M.A.; Greenwood, R.; et al. Structure-Guided Discovery of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of ERK1/2 from a Modestly Active and Promiscuous Chemical Start Point. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3438–3450.

- Mszar, N.W.; Haeffner, F.; Hoveyda, A.H. NHC–Cu-Catalyzed Addition of Propargylboron Reagents to Phosphinoylimines. Enantioselective Synthesis of Trimethylsilyl-Substituted Homoallenylamides and Application to the Synthesis of S-(−)-Cyclooroidin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3362–3365.

- Meyers, K.M.; Méndez-Andino, J.; Colson, A.-O.; Hu, X.E.; Wos, J.A.; Mitchell, M.C.; Hodge, K.; Howard, J.; Paris, J.L.; Dowty, M.; et al. Novel pyrazolopiperazinone- and pyrrolopiperazinone-based MCH-R1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 657–661.

- Brimble, M.; Brimble, M.; Hodges, R.; Lane, G. Synthesis of 2-Methylpyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2h)-one. Aust. J. Chem. 1988, 41, 1583–1590.

- Yoshimitsu, T.; Ino, T.; Futamura, N.; Kamon, T.; Tanaka, T. Total Synthesis of the β-Catenin Inhibitor, (−)-Agelastatin A: A Second-Generation Approach Based on Radical Aminobromination. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3402–3405.

- Shigeoka, D.; Kamon, T.; Yoshimitsu, T.; Stephenson, C. Formal synthesis of (−)-agelastatin A: An iron(II)-mediated cyclization strategy. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 860–865.

- Voievudskyi, M.; Astakhina, V.; Kryshchyk, O.; Petukhova, O.; Shyshkina, S. Synthesis and reactivity of novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives. Mon. Chem. 2015, 147, 783–789.

- Yenice, I.; Basceken, S.; Balci, M. Nucleophilic and electrophilic cyclization of N-alkyne-substituted pyrrole derivatives: Synthesis of pyrrolopyrazinone, pyrrolotriazinone, and pyrrolooxazinone moieties. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 825–834.

- Cetinkaya, Y.; Balci, M. Selective synthesis of N-substituted pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazin-1(2H)-one derivatives via alkyne cyclization. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6698–6702.

- Ito, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nishikawa, T. A concise synthesis of peramine, a metabolite of endophytic fungi. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 2053–2058.

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. A Novel Synthesis of Arylpyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazinone Derivatives. Molecules 2004, 9, 574–582.

- Dumas, D.J. Total synthesis of peramine. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4650–4653.

- Ujjinamatada, R.K. Substituted Tetrahydroquinoline Compounds as ROR Gamma Modulators. WO Patent No. 2016/185342 WIPO, 13 May 2016.

- Hewitt, J.F.M.; Williams, L.; Aggarwal, P.; Smith, C.D.; France, D. Palladium-catalyzed heteroallylation of unactivated alkenes—Synthesis of citalopram. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3538–3543.

- Smith, C.D.; Phillips, D.; Tirla, A.; France, D.J. Catalytic Isohypsic-Redox Sequences for the Rapid Generation of Csp3-Containing Heterocycles. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 17201–17204.

- Boothe, J.R.; Shen, Y.; Wolfe, J.P. Synthesis of Substituted γ- and δ-Lactams via Pd-Catalyzed Alkene Carboamination Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2777–2786.

- Trost, B.M.; Dong, G. New Class of Nucleophiles for Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation. Total Synthesis of Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6054–6055.

- Anderson, G.T.; Chase, C.E.; Koh, Y.-H.; Stien, D.; Weinreb, S.M.; Shang, M. Studies on Total Synthesis of the Cytotoxic Marine Alkaloid Agelastatin A. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 7594–7595.

- Stien, D.; Anderson, G.T.; Chase, C.E.; Koh, Y.-H.; Weinreb, S.M. Total Synthesis of the Antitumor Marine Sponge Alkaloid Agelastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9574–9579.

- Sun, X.-T.; Chen, A. Total synthesis of rac-longamide B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3459–3461.

- Trost, B.M.; Dong, G. A Stereodivergent Strategy to Both Product Enantiomers from the Same Enantiomer of a Stereoinducing Catalyst: Agelastatin A. Chem. A Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6910–6919.

- Dong, G. Recent advances in the total synthesis of agelastatins. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 2231–2246.

- Trost, B.M.; Osipov, M.; Dong, G. Palladium-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Asymmetric Transformations of Vinyl Aziridines with Nitrogen Heterocycles: Rapid Access to Biologically Active Pyrroles and Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15800–15807.

- Palomba, M.; Sancineto, L.; Marini, F.; Santi, C.; Bagnoli, L. A domino approach to pyrazino- indoles and pyrroles using vinyl selenones. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 7156–7163.

- Chizhova, M.; Khoroshilova, O.; Dar’In, D.; Krasavin, M. Unusually Reactive Cyclic Anhydride Expands the Scope of the Castagnoli–Cushman Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 12722–12733.

- Chizhova, M.E.; Dar’In, D.V.; Krasavin, M. The Castagnoli–Cushman reaction of bicyclic pyrrole dicarboxylic anhydrides bearing electron-withdrawing substituents. Mendeleev Commun. 2020, 30, 496–497.

- Ilyn, A.P.; Kuzovkova, J.A.; Potapov, V.V.; Shkirando, A.M.; Kovrigin, D.I.; Tkachenko, S.E.; Ivachtchenko, A.V. An efficient synthesis of novel heterocycle-fused derivatives of 1-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrazine using Ugi condensation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 881–884.

- Kounde, C.S.; Yeo, H.-Q.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Wan, K.F.; Dong, H.; Karuna, R.; Dix, I.; Wagner, T.; Zou, B.; Simon, O.; et al. Discovery of 2-oxopiperazine dengue inhibitors by scaffold morphing of a phenotypic high-throughput screening hit. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1385–1389.

- Imaoka, T.; Iwata, M.; Akimoto, T.; Nagasawa, K. Synthetic Approaches to Tetracyclic Pyrrole Imidazole Marine Alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 961–964.

- Kovvuri, V.R.R.; Xue, H.; Romo, D. Generation and Reactivity of 2-Amido-1,3-diaminoallyl Cations: Cyclic Guanidine Annulations via Net (3 + 2) and (4 + 3) Cycloadditions. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 1407–1413.

- Poullennec, K.G.; Romo, D. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Dibromophakellstatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6344–6345.

- Zöllinger, M.; Mayer, P.; Lindel, T. Total Synthesis of the Cytostatic Marine Natural Product Dibromophakellstatin via Three-Component Imidazolidinone Anellation. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 9431–9439.

- Jacquot, D.E.N.; Zöllinger, M.; Lindel, T. Total Synthesis of the Marine Natural Productrac-Dibromophakellstatin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2295–2298.

- Ma, Y.; De, S.; Chen, C. Syntheses of cyclic guanidine-containing natural products. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 1145–1173.

- Seiple, I.B.; Su, S.; Young, I.S.; Lewis, C.A.; Yamaguchi, J.; Baran, P.S. Total Synthesis of Palau’amine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 49, 1095–1098.

- Namba, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Kaihara, Y.; Oda, M.; Nakayama, A.; Nakayama, A.; Yoshida, M.; Tanino, K. Total synthesis of palau’amine. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8731.

- Robba, M.; Tembo, O.N.; Dallemagne, P.; Rault, S. An Efficient Synthesis of New Phenylpyrrolizine and Phenylpyrrolopyrazine Derivatives. Heterocycles 1993, 36, 2129.

- Fisher, T.E.; Kim, B.; Staas, D.D.; Lyle, T.A.; Young, S.D.; Vacca, J.P.; Zrada, M.M.; Hazuda, D.J.; Felock, P.J.; Schleif, W.A.; et al. 8-Hydroxy-3,4-dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1(2H)-one HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6511–6515.

- Sandoval, C.; Lim, N.-K.; Zhang, H. Two-Step Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrrolopyrazinones from Ketones and Piperazin-2-ones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1252–1255.

- Heaney, F.; Fenlon, J.; McArdle, P.; Cunningham, D. α-Keto amides as precursors to heterocycles—generation and cycloaddition reactions of piperazin-5-one nitrones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 1122–1132.

- Maisto, S.K.; Leersnyder, A.P.; Pudner, G.L.; Scheerer, J.R. Synthesis of Pyrrolopyrazinones by Construction of the Pyrrole Ring onto an Intact Diketopiperazine. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 9264–9271.

- Piltan, M.; Moradi, L.; Abasi, G.; Zarei, S.A.; Wolfe, J.P. A one-pot catalyst-free synthesis of functionalized pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline derivatives from benzene-1,2-diamine, acetylenedicarboxylates and ethyl bromopyruvate. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 510–515.

- Piltan, M. One-Pot, Green and Efficient Synthesis of Pyrrolo[1,2-α]Quinoxalines in Water. J. Chem. Res. 2016, 40, 410–412.

- Moradi, L.; Piltan, M.; Rostami, H.; Abasi, G. One-pot synthesis of pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazines via three component reaction of ethylenediamine, acetylenic esters and nitrostyrene derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2013, 24, 740–742.

- Alizadeh, A.; Abadi, M.H.; Ghanbaripour, R. An Efficient Approach to the Synthesis of Alkyl 7-Hydroxy-1-oxo-1,2,3,4- tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-8-carboxylates via a One-Pot, Three-Component Reaction. Synlett 2014, 25, 1705–1708.

- Piltan, M. One-pot synthesis of pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline and pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives via the three-component reaction of 1,2-diamines, ethyl pyruvate and α-bromo ketones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1507–1510.

- Aubert-Nicol, S.; Lessard, J.; Spino, C. A Photorearrangement To Construct the ABDE Tetracyclic Core of Palau’amine. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2615–2619.

- Jovanovic, M.; Petkovic, M.; Jovanovic, P.; Simic, M.; Tasic, G.; Eric, S.; Savic, V. Proline Derived Bicyclic Derivatives through Metal Catalysed Cyclisations of Allenes: Synthesis of Longamide B, Stylisine D and their Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2020, 295–305.

- Kostyanovsky, R.G.; El’Natanov, Y.I.; Chervin, I.I.; Antipin, M.Y.; Lyssenko, K.A. Unusual reaction of aziridine dimer with acetylene dicarboxylates. Mendeleev Commun. 1997, 7, 56–58.