Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lily Guo and Version 1 by Fatih M. Uckun.

Several cellular elements of the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment in multiple myeloma (MM) patients contribute to the immune evasion, proliferation, and drug resistance of MM cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated M2-like, “alternatively activated” macrophages, CD38+ regulatory B-cells (Bregs), and regulatory T-cells (Tregs).

- Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment

- cancer

- multiple myeloma

- immunomodulation

- bispecific antibodies

- CAR-T cells

- tyrosine kinases

- cytokines

- myeloid derived suppressor cells

- lactate shuttle

1. Introduction

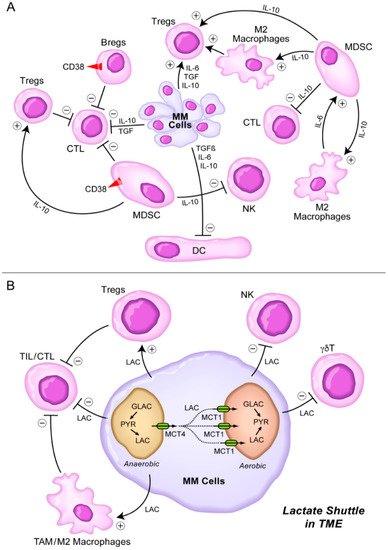

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is one of the main contributors of a marked immunobiological and clinical heterogeneity as well as clonal evolution in multiple myeloma (MM) [1,2,3][1][2][3]. Several cellular elements of the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment in MM patients contribute to the immune evasion, proliferation, and drug resistance of MM cells [4[4][5][6],5,6], including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated M2-like, “alternatively activated”, macrophages, CD38+ regulatory B-cells (Bregs), and regulatory T-cells (Tregs) [4,5,6][4][5][6] (Figure 1A). These immunosuppressive elements in bidirectional and multi-directional crosstalk with each other inhibit both memory and cytotoxic effector T-cell populations as well as natural killer (NK) cells [4,5,6][4][5][6]. MDSCs along with MM cell-derived interleukin 10 (IL-10) [7[7][8][9][10],8,9,10], TGF-β, and IL-6 are also known to impair dendritic cell (DC) maturation and their antigen-presenting function, which further accentuates the immunosuppression [6]. In addition to their immune-suppressive activity mediated by their secretion of IL-10 (an activator of Tregs and M2 macrophages), and TGF-β (an inhibitor of both cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells), M2 macrophages also promote MM cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and chemotherapy resistance [11,12,13][11][12][13] (Figure 1A). Nonclinical studies in animal models of MM have demonstrated that exosomes serve as regulators of the signaling networks within the BM microenvironment, activate anti-apoptotic mechanisms promoted by oncogenic proteins such as the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and cause immunosuppression by facilitating the growth of MDSCs [14,15,16,17,18,19][14][15][16][17][18][19]. Exosome-activated MDSCs have been implicated in development of other immunosuppressive cells, such as Tregs, tumor-promoting angiogenesis, proliferation of MM cells, and increased osteoclast activity contributing to the lytic bone lesions [14,15,16,17,18,19][14][15][16][17][18][19]. Complementing the immunosuppressive TME, T-cell exhaustion combined with high-level expression of immune-checkpoint ligands on MM cells are the main contributors to the immune evasion of MM cells [20,21,22,23][20][21][22][23].

Figure 1. Immunosuppressive TME in MM. (A) MM cells secrete several cytokines including IL-6, TGF-β (TGF), and IL-10 [7,8,9,10][7][8][9][10] that inhibit DCs, CTLs, but stimulate Tregs. MDSCs are stimulated by M2 macrophages via IL-6 and stimulate M2 macrophages as well as Tregs via IL-10. MDSC inhibit CTLs and NK cells via IL-10. See text for detailed discussion. (B) Lactate shuttle in TME. Lactate derived from MM cells stimulates Tregs and M2 macrophages, but it inhibits TILs, CTL, NK cells, and γδT cells. See text for detailed discussion.

2. Rationale of Targeting CD38, SLAMF7, CD137, and KIR as an Immunomodulatory Strategy against Immunosuppressive TME in MM

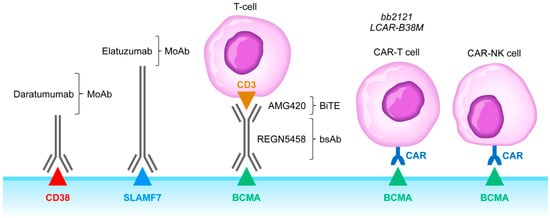

CD38 surface antigen is abundantly expressed on MM cells [30,34,35][24][25][26]. Anti-CD38 MoAb, including daratumumab (DARA), isatuximab (ISA), and MOR202 (Figure 2), have shown tolerability as well as meaningful clinical activity in FDA-approved monotherapy regimens and as components of FDA-approved multi-modality combination regimens for treatment of R/R MM patients [30,34,35,36][24][25][26][27]. Recently, a new formulation of DARA containing recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 has become available that can be administered subcutaneously [37][28]. DARA has increased the efficacy of the standard VLD regimen in ASCT-eligible patients and contributed to deep CRs with MRD negativity in the randomized GRIFFIN trial [38][29].

Figure 2. Monoclonal antibodies, BiTEs, BsAbs, CAR-T cells, and CAR-NK cells targeting MM cells. Abbreviations: MoAb: monoclonal antibody; BiTE: bispecific T-cell engager; bsAb: bispecific antibody; CAR-T: chimeric antigen receptor carrying T-cell; CAR-NK: chimeric antigen receptor carrying T-cell. See text for a detailed discussion of the rationale of targeting the CD38, SLAMF7, and BCMA receptors.

CD38-targeting MoAb such as DARA have been shown to cause complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), and tumor cell apoptosis [30][24]. However, CD38 is expressed on immunosuppressive cellular elements of the TME as well, including MDSCs and regulatory B-cells (Bregs) [2,20,23,30][2][20][23][24]. Krejcik et al. reported that DARA is capable of depleting CD38+ immune regulatory cells, thereby increasing the size of the immunoreactive clonal cytotoxic effector T-cell populations [39][30]. Biomarker analyses in R/R MM patients using a next-generation mass cytometry platform suggested a novel immunomodulatory mechanism of action associated with the activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells [40][31]. The immunomodulatory effects of DARA and other anti-CD38 MoAb may be useful to achieve clinical responses in IMiD-refractory MM patients using IMiD in salvage therapy following DARA monotherapy [30][24].

The CD38 antibodies also improve host-anti-tumor immunity by elimination of regulatory T-cells, regulatory B-cells, and MDSCs [41,42][32][33]. Mechanisms of primary and/or acquired resistance include tumor-related factors. It has been shown that increased expression levels of complement inhibitors CD55 and CD59 as well as decreased cell surface expression levels of CD38 on MM cells may confer resistance to anti-CD38 MoAb [35][26], whereas certain KIR and HLA genotypes are associated with higher effectiveness of treatment regimens employing anti-CD38 MoAb [35][26]. Therefore, biomarker-guided patient-tailored application of anti-CD38 MoAb may further improve their clinical impact potential in MM therapy.

SLAMF7 surface antigen is expressed on both MM cells and plays an important role in MM cell adhesion to protective BM stroma (Figure 2). SLAMF7 has been implicated in negative regulation of NK cell function as well. The FDA-approved anti-SLAMF7 MoAb elotuzumab impairs the viability and survival of MM cells by blocking the protective effects of stromal cells and by potentiating NK cell activity against MM cells [30,43][24][34]. A Phase 3 clinical trial in R/R MM (ELOQUENT-2, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01239797) demonstrated the addition of elotuzumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone significantly improves the survival outcomes when compared to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone combination [30,44][24][35]. Likewise, the addition of elotuzumab topomalidomide plus dexamethasone resulted in significantly better survival outcomes in another Phase 3 study (ELOQUENT-3, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02654132) [45][36]. Unfortunately, inclusion of this immunostimulatory antibody in combination regimens against MM resulted in a higher incidence of infections and secondary cancers [46][37]. Other immunostimulatory antibodies have been considered in combination regimens with elotuzumab against MM, including the T-cell activating 4-1BB/CD137 agonist antibodies urelumab or utomilumab and the NK cell activating anti-KIR antibody lirilumab (NCT02252263) [47,48][38][39]. Due to potentially life-threatening hepatotoxicity of urelumab, some of these combination regimens will require specifically designed risk mitigation strategies.

References

- Schürch, C.M.; Rasche, L.; Frauenfeld, L.; Weinhold, N.; Fend, F. A review on tumor heterogeneity and evolution in multiple myeloma: Pathological, radiological, molecular genetics, and clinical integration. Virchows Arch. 2019, 476, 337–351.

- Holthof, L.C.; Mutis, T. Challenges for Immunotherapy in Multiple Myeloma: Bone Marrow Microenvironment-Mediated Immune Suppression and Immune Resistance. Cancers 2020, 12, 988.

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Vacca, A. Importance of the bone marrow microenvironment in inducing the angiogenic response in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4257–4266.

- Kawano, Y.; Moschetta, M.; Manier, S.; Glavey, S.; Görgün, G.T.; Roccaro, A.M.; Anderson, K.C.; Ghobrial, I.M. Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 263, 160–172.

- García-Ortiz, A.; Rodríguez-García, Y.; Encinas, J.; Maroto-Martín, E.; Castellano, E.; Teixidó, J.; Martínez-López, J. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Multiple Myeloma Development and Progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 217.

- Caraccio, C.; Krishna, S.; Phillips, D.J.; Schürch, C.M. Bispecific Antibodies for Multiple Myeloma: A Review of Targets, Drugs, Clinical Trials, and Future Directions. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 501.

- Kovacs, E. Interleukin-6 leads to interleukin-10 production in several human multiple myeloma cell lines. Does interleukin-10 enhance the proliferation of these cells? Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 912–916.

- Otsuki, T.; Yamada, O.; Yata, K.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kurebayashi, J.; Yawata, Y.; Ueki, A. Expression and production of interleukin 10 in human myeloma cell lines. Br. J. Haematol. 2000, 111, 835–842.

- Otsumi, T.; Yata, K.; Sakaguchi, H.; Uno, M.; Fujii, T.; Wada, H.; Sugihara, T.; Ueki, A. IL-10 in Myeloma Cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2002, 43, 969–974.

- Matsumoto, M.; Baba, A.; Yokota, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Ohkawa, Y.; Kayama, H.; Kallies, A.; Nutt, S.L.; Sakaguchi, S.; Takeda, K.; et al. Interleukin-10-Producing Plasmablasts Exert Regulatory Function in Autoimmune Inflammation. Immunity 2014, 41, 1040–1051.

- Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Sinha, P.; Beury, D.W.; Clements, V.K. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), macrophages, and dendritic cells enhances tumor-induced immune suppression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2012, 22, 275–281.

- Urashima, M.; Ogata, A.; Chauhan, D.; Hatziyanni, M.; Vidriales, M.; Dedera, D.; Schlossman, R.; Anderson, K. Transforming growth factor-beta1: Differential effects on multiple myeloma versus normal B cells. Blood 1996, 87, 1928–1938.

- Nakamura, K.; Kassem, S.; Cleynen, A.; Chrétien, M.-L.; Guillerey, C.; Putz, E.M.; Bald, T.; Förster, I.; Vuckovic, S.; Hill, G.R.; et al. Dysregulated IL-18 Is a Key Driver of Immunosuppression and a Possible Therapeutic Target in the Multiple Myeloma Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 634–648.

- Chen, T.; Moscvin, M.; Bianchi, G. Exosomes in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Multiple Myeloma in the Context of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 8815.

- Moloudizargari, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Asghari, M.H.; Zimta, A.A.; Neagoe, I.B.; Nabavi, S.M. The emerging role of exosomes in multiple myeloma. Blood Rev. 2019, 38, 100595.

- Li, M.; Xia, B.; Wang, Y.; You, M.J.; Zhang, Y. Potential Therapeutic Roles of Exosomes in Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Review. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 6154–6160.

- Raimondo, S.; Urzì, O.; Conigliaro, A.; Bosco, G.L.; Parisi, S.; Carlisi, M.; Siragusa, S.; Raimondi, L.; de Luca, A.; Giavaresi, G.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle microRNAs Contribute to the Osteogenic Inhibition of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2020, 12, 449.

- Raimondi, L.; de Luca, A.; Fontana, S.; Amodio, N.; Costa, V.; Carina, V.; Bellavia, D.; Raimondo, S.; Siragusa, S.; Monteleone, F.; et al. Multiple Myeloma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Osteoclastogenesis through the Activation of the XBP1/IRE1α Axis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2167.

- Wang, J.; de Veirman, K.; Faict, S.; Frassanito, M.A.; Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A.; Menu, E. Multiple myeloma exosomes establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J. Pathol. 2016, 239, 162–173.

- Soekojo, C.Y.; Ooi, M.; De Mel, S.; Chng, W.J. Immunotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2020, 9, 601.

- Costello, C. The future of checkpoint inhibition in multiple myeloma? Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e439–e440.

- Yamamoto, L.; Amodio, N.; Gulla, A.; Anderson, K.C. Harnessing the Immune System Against Multiple Myeloma: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 6368.

- Minnie, S.A.; Hill, G.R. Immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1565–1575.

- Uckun, F.M.; Qazi, S.; Demirer, T.; Champlin, R.E. Contemporary patient-tailored treatment strategies against high risk and relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. EBioMedicine 2019, 39, 612–620.

- Van de Donk, N.W.C.J.; Richardson, P.G.; Malavasi, F. CD38 antibodies in multiple myeloma: Back to the future. Blood 2018, 131, 13–29.

- Chong, L.L.; Soon, Y.Y.; Soekojo, C.Y.; Ooi, M.; Chng, W.J.; de Mel, S. Daratumumab-based induction therapy for multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 103211.

- Giri, S.; Grimshaw, A.; Bal, S.; Godby, K.; Kharel, P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Facon, T.; Usmani, S.Z.; Mateos, M.-V.; et al. Evaluation of Daratumumab for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma in Patients with High-risk Cytogenetic Factors. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1759.

- Mateos, M.-V.; Nahi, H.; Legiec, W.; Grosicki, S.; Vorobyev, V.; Spicka, I.; Hungria, V.; Korenkova, S.; Bahlis, N.; Flogegard, M.; et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous daratumumab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (COLUMBA): A multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e370–e380.

- Voorhees, P.M.; Kaufman, J.L.; Laubach, J.P.; Sborov, D.W.; Reeves, B.; Rodriguez, C.; Chari, A.; Silbermann, R.; Costa, L.J.; Anderson, L.D.; et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: The GRIFFIN trial. Blood 2020, 136, 936–945.

- Krejcik, J.; Casneuf, T.; Nijhof, I.S.; Verbist, B.; Bald, J.; Plesner, T.; Syed, K.; Liu, K.; van de Donk, N.W.; Weiss, B.M.; et al. Daratumumab depletes CD38+ immune regulatory cells, promotes T-cell expansion, and skews T-cell repertoire in multiple myeloma. Blood 2016, 128, 384–394.

- Adams, H.C.; Stevenaert, F.; Krejcik, J.; van der Borght, K.; Smets, T.; Bald, J.; Abraham, Y.; Ceulemans, H.; Chiu, C.; Vanhoof, G.; et al. High-Parameter Mass Cytometry Evaluation of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Patients Treated with Daratumumab Demonstrates Immune Modulation as a Novel Mechanism of Action. Cytom. Part A 2019, 95, 279–289.

- Van de Donk, N.W. Immunomodulatory effects of CD38-targeting antibodies. Immunol. Lett. 2018, 199, 16–22.

- Van de Donk, N.W.; Usmani, S.Z. CD38 Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: Mechanisms of Action and Modes of Resistance. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2134.

- Campbell, K.S.; Cohen, A.D.; Pazina, T. Mechanisms of NK Cell Activation and Clinical Activity of the Therapeutic SLAMF7 Antibody, Elotuzumab in Multiple Myeloma. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2551.

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Lonial, S.; Betts, K.A.; Chen, C.; Zichlin, M.L.; Brun, A.; Signorovitch, J.E.; Makenbaeva, D.; Mekan, S.; Sy, O.; et al. Elotuzumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Extended 4-year follow-up and analysis of relative progression-free survival from the randomized ELOQUENT-2 trial. Cancer 2018, 124, 4032–4043.

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Dytfeld, D.; Grosicki, S.; Moreau, P.; Takezako, N.; Hori, M.; Leleu, X.; Leblanc, R.; Suzuki, K.; Raab, M.S.; et al. Elotuzumab plus Pomalidomide and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1811–1822.

- Trudel, S.; Moreau, P.; Touzeau, C. Update on elotuzumab for the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Patients’ selection and perspective. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 5813–5822.

- Ochoa, M.C.; Perez-Ruiz, E.; Minute, L.; Oñate, C.; Perez, G.; Rodriguez, I.; Zabaleta, A.; Alignani, D.; Fernandez-Sendin, M.; Lopez, A.; et al. Daratumumab in combination with urelumab to potentiate anti-myeloma activity in lymphocyte-deficient mice reconstituted with human NK cells. OncoImmunology 2019, 8, e1599636.

- Guillerey, C.; Nakamura, K.; Pichler, A.C.; Barkauskas, D.; Krumeich, S.; Stannard, K.; Miles, K.; Harjunpää, H.; Yu, Y.; Casey, M.; et al. Chemotherapy followed by anti-CD137 mAb immunotherapy improves disease control in a mouse myeloma model. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e125932.

More