Glioblastoma (GBM), a grade IV glioma, continues to have one of the highest mortality rates among central nervous system tumors. Metabolomics is a particularly promising tool for the analysis of GBM tumors and potential methods of treating them, as it is the only “omics” approach that is capable of providing a metabolic signature of a tumor’s phenotype.

- glioblastoma multiforme

- in vitro metabolomics

- phamacometabolomics

1. Introduction

The metabolomic reprogramming of cancer cells is a well-known phenomenon. The stressful environment created by hypoxia generally impairs oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle activity in the intensely proliferating tumor cells and enhances glycolysis and lactic acid production - the Warburg effect. It is indirectly strengthened by HIF-1 expression in hypoxic environments. However, it remains unclear how exactly hypoxia influences the metabolomic reprogramming of tumor cells. As such, the development of models that more accurately represent tumor microenvironment metabolomics is required [1][2][3].

The metabolomic reprogramming of cancer cells is a well-known phenomenon. The stressful environment created by hypoxia generally impairs oxidative phosphorylation and TCA cycle activity in the intensely proliferating tumor cells and enhances glycolysis and lactic acid production - the Warburg effect. It is indirectly strengthened by HIF-1 expression in hypoxic environments. However, it remains unclear how exactly hypoxia influences the metabolomic reprogramming of tumor cells. As such, the development of models that more accurately represent tumor microenvironment metabolomics is required [17,18,19].

Metabolomics, along with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, comprise the group of sciences known as “Omics.” Metabolomics focuses on the analysis of small molecules (<1.5 kDa) produced as a result of metabolism [4]. It is possible to obtain a relatively full picture of the state of a given cell or tissue by analyzing its endogenous and exogenous metabolites [5]. The great advantage of metabolomics is that the metabolome accurately mirrors the phenotype and influence of factors external to the analyzed cell, which cannot be captured as precisely with genomics or proteomics [6].

Metabolomics, along with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, comprise the group of sciences known as “Omics.” Metabolomics focuses on the analysis of small molecules (<1.5 kDa) produced as a result of metabolism [20]. It is possible to obtain a relatively full picture of the state of a given cell or tissue by analyzing its endogenous and exogenous metabolites [21]. The great advantage of metabolomics is that the metabolome accurately mirrors the phenotype and influence of factors external to the analyzed cell, which cannot be captured as precisely with genomics or proteomics [22].

Recently, in vitro studies using both established GBM cell lines and primary GBM cells have been gaining in popularity due to rapid developments in 3D in vitro culture techniques. Standard monolayer culture is easy to conduct, as protocols for culturing and testing 2D cell cultures were well established through the years. In turn, 3D cell culture reflects in vivo tumor complexity better, yet it is a relatively new culture method and standard culturing and testing protocols are yet to be established. Nevertheless, with appropriate experimental design, metabolomics of GBM cell cultures can deliver information about alternate metabolic pathways, potential biomarkers, and with proper in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE), drug development and repurposing.

2. Metabolomics of GBM In Vitro

Prior studies have successfully detected numerous metabolic alterations, particularly in relation to the metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids, such as Gln, choline (Cho), and cysteine (Cys) [7][8][9][10]. However, these findings represent only a small fraction of the work that has been done in GBM metabolomics and lipidomics. In vitro studies using both established cell lines and primary cells ensure replicable and strictly controlled conditions between each replicate sample. Furthermore, the analysis of culture media and disintegrated cells, along with careful sample preparation, can provide useful information about both the endo- and exo-metabolome. However, cells growing in vitro as a monolayer do not adequately recreate the tumor microenvironment. As such, researchers have increasingly been exploring the use of three-dimensional (3D) in vitro culture models, as they reflect the actual tumor phenotype more adequately than standard 2D cell cultures [11].

Prior studies have successfully detected numerous metabolic alterations, particularly in relation to the metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids, such as Gln, choline (Cho), and cysteine (Cys) [63,64,65,66]. However, these findings represent only a small fraction of the work that has been done in GBM metabolomics and lipidomics. In vitro studies using both established cell lines and primary cells ensure replicable and strictly controlled conditions between each replicate sample. Furthermore, the analysis of culture media and disintegrated cells, along with careful sample preparation, can provide useful information about both the endo- and exo-metabolome. However, cells growing in vitro as a monolayer do not adequately recreate the tumor microenvironment. As such, researchers have increasingly been exploring the use of three-dimensional (3D) in vitro culture models, as they reflect the actual tumor phenotype more adequately than standard 2D cell cultures [67].

Metabolic alterations in cancer cells have long been explored for their usefulness in profiling of the phenotypes of many different types of tumors [12]. Inositol and myo-inositol are two metabolites that could potentially be useful in GBM diagnostics and prognostics, as they are known to play roles in osmoregulation and phosphatidylinositol lipids synthesis [13]. Gln, glutamate (Glu), and γ-amniobutyric acid (GABA) each play an extremely important role in brain development. Changes in the metabolism of Gln can cause disturbances in Glu, GABA, and aspartate (Asp), as it is the precursor of these neurotransmitters [14]. Furthermore, Gln can be converted into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which subsequently takes part in the TCA cycle [15]. Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide that is composed of Glu, Cys, and glycine (Gly) and it can take on two forms, namely reduced GSH and oxidized GSSG, which allows it to play an important role in redox regulation and protecting cells from ROS [16]. 2-HG is a good oncotarget for use in differentiating low-grade gliomas from GBMs, with Gln and glucose deprivation serving as useful therapeutic targets for such analyses [

Metabolic alterations in cancer cells have long been explored for their usefulness in profiling of the phenotypes of many different types of tumors [68]. Inositol and myo-inositol are two metabolites that could potentially be useful in GBM diagnostics and prognostics, as they are known to play roles in osmoregulation and phosphatidylinositol lipids synthesis [72]. Gln, glutamate (Glu), and γ-amniobutyric acid (GABA) each play an extremely important role in brain development. Changes in the metabolism of Gln can cause disturbances in Glu, GABA, and aspartate (Asp), as it is the precursor of these neurotransmitters [74]. Furthermore, Gln can be converted into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which subsequently takes part in the TCA cycle [75]. Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide that is composed of Glu, Cys, and glycine (Gly) and it can take on two forms, namely reduced GSH and oxidized GSSG, which allows it to play an important role in redox regulation and protecting cells from ROS [76]. 2-HG is a good oncotarget for use in differentiating low-grade gliomas from GBMs, with Gln and glucose deprivation serving as useful therapeutic targets for such analyses [

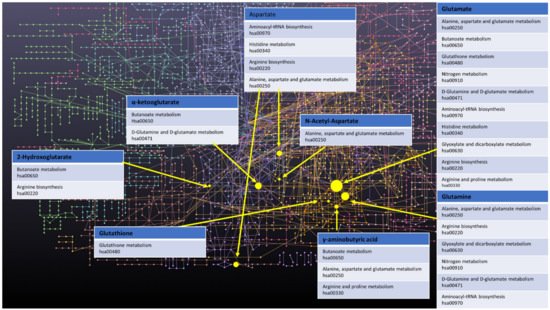

Finally, a few other metabolites and altered pathways, such as N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), have been suggested as important for GBM metabolomic diagnostics, prognosis, and drug testing [17][18]. The most prevalent metabolic pathways are shown in the

Finally, a few other metabolites and altered pathways, such as N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), have been suggested as important for GBM metabolomic diagnostics, prognosis, and drug testing [37,52]. The most prevalent metabolic pathways are shown in the

Figure 1. Network of GBM related oncometabolites. Network generated with the MetaboAnalyst 5.0 online [19][79], pathways names and codes from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database [20][80].

3. Importance of GBM Microenvironment Reconstruction for In Vitro Metabolomics

GBM is a tumor that is known to have a highly complicated microenvironment, largely due to its heterogeneous nature, intratumor hypoxia, and angiogenesis [21][22]. Therefore, to carry out metabolomic in vitro studies that will translate to an in vivo environment, it is extremely important to consider culture conditions and cell source in metabolomic testing. In order to pursue a truly accurate metabolomic analysis of GBM in vitro, it should be taken into account that standard culture conditions established over the years, e.g., 2D cell culture, culture medium supplemented with FBS, and normoxic conditions, do not accurately reflect the complexity of the tumor. When planning the experiment, it is advisable to conduct simultaneous experiment with the use of 3D cell culture, FBS-free medium and under hypoxic conditions.

GBM is a tumor that is known to have a highly complicated microenvironment, largely due to its heterogeneous nature, intratumor hypoxia, and angiogenesis [14,15]. Therefore, to carry out metabolomic in vitro studies that will translate to an in vivo environment, it is extremely important to consider culture conditions and cell source in metabolomic testing. In order to pursue a truly accurate metabolomic analysis of GBM in vitro, it should be taken into account that standard culture conditions established over the years, e.g., 2D cell culture, culture medium supplemented with FBS, and normoxic conditions, do not accurately reflect the complexity of the tumor. When planning the experiment, it is advisable to conduct simultaneous experiment with the use of 3D cell culture, FBS-free medium and under hypoxic conditions.

4. In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation of Oncometabolites

To date, several low-molecular-weight compounds have been identified as possible biomarkers of GBM. In particular, the dysregulation of the oncometabolites: 2-HG [23][24][25], NAA [26], Glu [8], and α-KG) [8] has been shown to be connected to the altered enzymatic pathways that occur within cancerous cells. Thus, these low-molecular-mass compounds are potential targets for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. All of the above-mentioned compounds were identified through a literature search. Both, 2-HG and Glu were found via live cell monitoring using 13C-MRS, wherein cell culture medium was supplemented with 3-13C-glutamine. This enabled the determination of 13C-Glu and 13C-2-HG in U87IDHmut, and the determination of 13C-Glu only in U87IDHwt cells [27]. Consequently, in terms of IVIVE, Glu and 2-HG can serve not only as GBM biomarkers, but also as markers of

To date, several low-molecular-weight compounds have been identified as possible biomarkers of GBM. In particular, the dysregulation of the oncometabolites: 2-HG [83,84,85], NAA [86], Glu [64], and α-KG) [64] has been shown to be connected to the altered enzymatic pathways that occur within cancerous cells. Thus, these low-molecular-mass compounds are potential targets for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. All of the above-mentioned compounds were identified through a literature search. Both, 2-HG and Glu were found via live cell monitoring using 13C-MRS, wherein cell culture medium was supplemented with 3-13C-glutamine. This enabled the determination of 13C-Glu and 13C-2-HG in U87IDHmut, and the determination of 13C-Glu only in U87IDHwt cells [45]. Consequently, in terms of IVIVE, Glu and 2-HG can serve not only as GBM biomarkers, but also as markers of

IDH1

mutation, which plays key role in chemotherapy treatment optimization.

Table 3.

In vivo-in vitro extrapolation of oncometabolites in the reviewed literature.

| Compound | In Vitro Model | In Vivo/Ex Vivo Investigation |

|---|

| NAA | Primary glioblastoma [18] T98G and primary [17] | Primary glioblastoma [52] T98G and primary [37] |

[28][29][30][31] | [87,88,89,90] | ||||

| 2HG | U87, NHA [27] U87, NHA, BT54, BT142 | U87, NHA [45 | [27] | ] U87, NHA, BT54, BT142 [45] |

[29][30][[33] | [88 | 31][32] | ,89,90,91,92] |

| Glu | U87 [34] A172, LN18, LN71, LN229, LN319, LN405, U373, U373R [35] Res 259, Res186, BT66, JHH-NF1-PA1 [36] Primary glioblastoma [18] U 87 [37] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [38] T98G and primary [17] JHH520 GBM1, 23, 233, 268, 349, 407, SF188, NCH644 [39] U87 [40] Primary, U87-MG [41] MOG-G-VW, LN-18, LN-229, SF-188, U-251 MG, U-87 MG, Primary rat astrocytes, Primary human GBM: E2, R10, R24 [42] U87, NHA [43] U87, NHA, BT54, BT142 | ] A172, LN18, LN71, LN229, LN319, LN405, U373, U373R [47] Res 259, Res186, BT66, JHH-NF1-PA1 [49] Primary glioblastoma [52] U 87 [38] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [35 | [27] CHG5, SHG44, U87, U118, U251 [44] LN229, VLN319m [45] BT4C (rat) [46] | U87 [46] T98G and primary [37] JHH520 GBM1, 23, 233, 268, 349, 407, SF188, NCH644 [54] U87 [36] Primary, U87-MG [32] MOG-G-VW, LN-18, LN-229, SF-188, U-251 MG, U-87 MG, Primary rat astrocytes, Primary human GBM: E2, R10, R24 [26] U87, NHA [33] U87, NHA, BT54, BT142 [45] CHG5, SHG44, U87, U118, U251 [34] LN229, VLN319m [30] BT4C (rat) [44] |

[28][33][47][48] | [87,92,93,94] | ||

| α-KG | Not found | [47][48] | [93,94] | |||||

| PC | BT4C (rat) [46] Primary glioblastoma [18] U87 [37] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [38] HT1080 [49] | BT4C (rat) [44] Primary glioblastoma [52] U87 [38] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [35] HT1080 [39] |

[28][50][51][52][53] | [87,95,96,97,98] | ||||

| Lactic acid | LN229, VLN319 [45] U118 LN-18 A172 NHA [54] U87 [34] A172, LN18, LN71, LN229, LN319, LN405, U373, U373R [35] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [38] U87 [40] CHG5, SHG44, U87, U118, U251 [44] BT4C (rat) | LN229, VLN319 [30 | [46 | ] U118 LN-18 A172 NHA [55 | ] | ] U87 [46] A172, LN18, LN71, LN229, LN319, LN405, U373, U373R [47] Self-derived cell lines: GBM1, 040922, GBM1016, GBM1417; commercial cell lines: LN229, U87 [35] U87 [36] CHG5, SHG44, U87, U118, U251 [34] BT4C (rat) [44] |

[29] | [88] |

| Palmitic acid | U87 [34] | U87 [46] | [29][55] | [88 | [56] | ,99,100] | ||

| Stearic acid | NG97 [57] LN229, SNB19, GAMG, U118, T98G, U87, NHA [57] | NG97 [58] LN229, SNB19, GAMG, U118, T98G, U87, NHA [58] |

[29][56] | [88,100] |

5. Pharmaco-Metabolomics as a Tool for Glioma Drug Testing In Vitro

Thanks to the extensive work that was conducted to identify potential metabolites for glioma diagnostics and prognostics, cell cultures have emerged as a truly promising model for drug testing and the exploration of tumor resistance to therapy. Knowledge regarding significant pathways and alterations to their metabolism could be used to predict the effectiveness of different therapeutics depending on the phenotype of the cells. Moreover, metabolomics can also be used to assess cytotoxicity in in vitro applications, for example, particles for gene transfection [57]. Chemoterapeitics such as GLS inhibitors, CBPs, Gli1 inhibitor, Notch inhibitor, FK866 inhibitor, PLD inhibitor, or gamma-linoleic acid [

Thanks to the extensive work that was conducted to identify potential metabolites for glioma diagnostics and prognostics, cell cultures have emerged as a truly promising model for drug testing and the exploration of tumor resistance to therapy. Knowledge regarding significant pathways and alterations to their metabolism could be used to predict the effectiveness of different therapeutics depending on the phenotype of the cells. Moreover, metabolomics can also be used to assess cytotoxicity in in vitro applications, for example, particles for gene transfection [58]. Chemoterapeitics such as GLS inhibitors, CBPs, Gli1 inhibitor, Notch inhibitor, FK866 inhibitor, PLD inhibitor, or gamma-linoleic acid [

have been studied with the use of GBM in vitro metabolimics.

The knowledge gained from the basic research discussed in metabolomic paragraph has been successfully used to select markers to determine the efficiency and target specificity of targeted drugs, making metabolomics in vitro an interesting tool for novel targeted therapies development. Gln, Glu, and GSH metabolism being especially useful in determining the effectiveness of analyzed drugs.

6. Conclusions

Factors such as culture model, medium composition, established or patient-derived cell lines, and oxygen levels should all be chosen based on desired aspects of a tumor’s particular microenvironment. Moreover, sample preparation should use only the most effective metabolism quenching or extraction methods. In vitro studies face a problem at the level of in vitro-in vivo extrapolation, as metabolic reactions in a living organism are much more complex than in vitro environments are able to capture. However, with careful design, e.g., the use of 3D culture models, hypoxic conditions when conducting a study, or usage of more efficient sample preparation methods, in vitro studies on GBM metabolomics can be extremely useful for the diagnosis and prognosis of brain tumors, as well as for studying new drugs or mechanisms of drug resistance.