Photorespiration, or C2 photosynthesis, is generally considered a futile cycle that potentially decreases photosynthetic carbon fixation by more than 25%. Nonetheless, many essential processes, such as nitrogen assimilation, C1 metabolism, and sulfur assimilation, depend on photorespiration. Most studies of photosynthetic and photorespiratory reactions are conducted with magnesium as the sole metal cofactor despite many of the enzymes involved in these reactions readily associating with manganese. Indeed, when manganese is present, the energy efficiency of these reactions may improve.

- photorespiration

- oxygenation

- photosynthesis

- metal cofactor

- atmospheric CO2

- climate change

- crop yield

- metabolic interactions

- kinetics

1. Introduction

Photorespiration involves the oxygenation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) to form 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA) and 2-phosphoglycolate (2PG) and the subsequent carbon oxidation pathways that release CO

under light conditions [1][2][3][4][5]. Because it produces 2PG, a compound “toxic” to many enzymes in photosynthetic metabolism, and oxidizes organic carbon without seemingly generating ATP, photorespiration is generally considered a wasteful process. The following sections examines how the photorespiratory pathway converts 2PG into glycolate, the only carbon source for the photosynthetic carbon oxidation cycle [6], a cycle that together with nitrogen assimilation, C

metabolism, and sulfur assimilation generates essential amino acids and intermediate compounds [7]. Moreover, the three enzymes involved in the initial photorespiratory steps within chloroplasts—Rubisco, malic enzyme, and phosphoglycolate phosphatase—have metal binding sites that accommodate either Mg

or Mn

, and balance between the binding of these enzymes to Mg

or Mn

may shift the relative rates and energy efficiencies of photosynthesis and photorespiration [8].

2. Photosynthesis vs. Photorespiration

2.1. Rubisco

Atmospheric CO

concentration has increased more than 20% during the past 35 years [9]. The major sink for this CO

is the approximately 258 billion tons per year that photosynthetic organisms convert into organic carbon compounds through carbon fixation via the Calvin–Benson pathway [10]. This pathway begins with Rubisco (Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase–oxygenase), the most abundant protein on the planet [11].

Rubisco comes in three forms [12]:

Form I, which is found in cyanobacteria, proteobacteria, chlorophyte algae, heterokont algae, and haptophyte algae, and higher plants, is the most common [13][14]. It is a hexadecamer containing eight identical large subunits (~55,000

), each with a metal-binding site, and eight small subunits (~15,000

). The large subunits are coded by a single plastomic gene, whereas the small subunits are coded by a nuclear multigene family that consists of 2 to 22 members, depending on the species [15]. Complex cellular machinery is required to assemble this form of Rubisco and to maintain its activity [16]. Form I Rubisco, until recently, had resisted all efforts to generate a functional holoenzyme in vitro or upon recombinant expression in

[17].

Form II Rubisco, found in proteobacteria, archaea, and dinoflagellate algae, contains one or more isodimers with subunits that share about 30% identity to the large subunit of Form I Rubisco [8].

Form III Rubisco, found in archaea, has one or five isodimers composed of subunits homologous to the large subunit of Form I Rubisco [8].

Form II and Form III Rubisco show greater similarity in their primary sequence to one another than either do to the large subunit of Form I Rubisco [8].

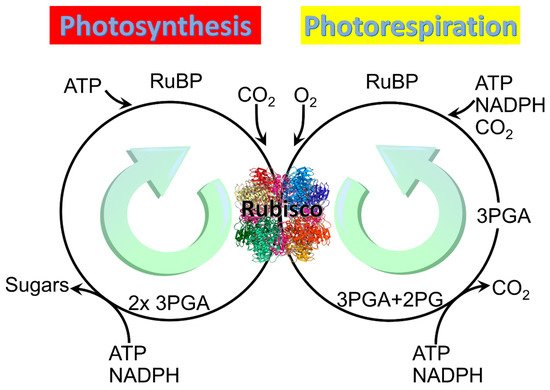

All three forms of Rubisco catalyze not only the reaction in which the carboxylation of the five-carbon sugar RuBP generates two molecules of the three-carbon organic acid 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA), but also an alternative reaction in which oxidation of RuBP generates one molecule of 3PGA and one of 2PG (

) [8]. The carboxylation pathway of photosynthesis expends 3 ATP and 2 NADPH per RuBP regenerated and produces a carbon in hexose [18], whereas the oxygenation pathway of photorespiration reportedly expends 3.5 ATP and 2 NADPH per RuBP regenerated but produces no additional organic carbon [19][20].

Two main reactions of Rubisco: Photosynthesis and photorespiration. Rubisco structure picture credit: Laguna design / science photo library.

Rubisco must be activated before it can carboxylate or oxygenate RuBP. Activation of the three forms of Rubisco involves binding of Mn

or Mg

requires carbamylation of Rubisco by the addition of CO

. One histidine at the active site of Rubisco rotates into an alternate conformation, resulting in a transient binding site where Mg

is partially neutralized by the conversion of two water molecules to hydroxide ions and coordinated indirectly by three histidine residues through the water molecules. Subsequently, the hydroxide ions cause a lysine residue at the active site to become deprotonated and rotate 120 degrees into the

conformer, which brings its nitrogen into close proximity to the carbon of CO

, allowing for the formation of a covalent bond that produces a carbamyl group. This carbamyl group causes the Mg

ion to transfer to a second binding site, after which the histidine that first rotated returns to its original conformation [23]. It is unclear whether binding Mn

follows a similar mechanism and whether it requires an activator CO

to be bound first [21][22]; hence, understanding the mechanism of Mn

binding to Rubisco is important to future research on Rubisco kinetics. During in vitro studies, Rubisco is often activated at pH 8.0 in the presence of CO

and either Mg

or Mn

.

Rubisco can also bind to other metals. When bound to Fe

, Ni

, Cu

, Ca

, or Co

, Rubisco may exhibit some carboxylase and oxygenase activity [24]. For example, one study found that Rubisco from

, when bound to Co

, was incapable of carboxylation but still capable of oxygenation [24]. Another study found that Rubisco from spinach performed both carboxylation and oxygenation when bound to Ni

or Co

[25]. When bound to some other metal ions, including Cd

, Cr

, and Ga

, Rubisco cannot catalyze either carboxylation or oxygenation [24]. Although it is known that the metal ion plays a role in stabilizing the activator carbamate and determining the active site’s structure, its effect upon the reactions catalyzed by Rubisco is still not completely understood. One hypothesis is that Mg

, because of its electron-withdrawing properties, polarizes the C2 carbonyl of RuBP, which favors the removal of the C3 proton and thereby contributes to enolization [21].

NADPH complexes strongly with Rubisco and acts as an effector molecule to maintain the Rubisco catalytic pocket in an open confirmation that more rapidly facilitates CO

-Mg

activation when CO

and Mg

are present in suboptimal concentrations [26][27][28][29]. The crystal structure of Rubisco with both Mg

and NADPH as ligands indicates that NADPH binds to the catalytic site of Rubisco through metal-coordinated water molecules [26]. The activated enzyme catalyzes either carboxylation or oxygenation of the enediol form of the five-carbon sugar ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) [14][21][22][30][31].

2.2. Balance between Carboxylation and Oxygenation and Metal Cofactors

Several factors alter the balance between Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation and, thereby, alter the relative rates of photosynthesis and photorespiration. These include the concentrations of CO

and O

at the active site of Rubisco, the specificity of the enzyme for each gas, and whether the enzyme is associated with Mg

or Mn

[32]. These divalent cations share the same binding site in Rubisco [14][22][33], and in tobacco, Rubisco associates with both metals and rapidly exchanges one metal for the other [32]. Nonetheless, nearly all recent studies on the photosynthetic and photorespiratory pathways have been conducted in the presence of Mg

and absence of Mn

[8]. Rubisco binding of Mg

accelerates carboxylation, whereas binding of Mn

slows carboxylation [25][34][35][36][37][38]. Chloroplastic Mg

and Mn

activities seem to be regulated at the cellular level because in isolated tobacco chloroplasts, activities of the metals were directly proportional to their concentrations in the medium [32]. The thermodynamics of binding Mg

to Rubisco were similar for enzymes isolated from a Form I and a Form II species [32]. By contrast, the thermodynamics of binding differed greatly between the two Rubisco forms when the enzymes were associated with Mn

[32].

Mg

and Mn

have nearly identical ionic radii but highly disparate electron configurations: Mg

(1s

2s

2p

or [Ne]) has a very stable outer shell [8], whereas Mn

has five unpaired d electrons (1s

2s

2p

3s

3p

3d

or [Ar]3d

) that are susceptible to many redox reactions. An aerated solution of activated Mn

-Rubisco exhibits a long-lived chemiluminescence when RuBP is added [39][40]. This chemiluminescence was attributed to a spin-flip within the Mn

3d manifold, leading to an excited quartet (

=

/

) d

electronic configuration that decays over the course of 1 to 5 min back to the sextet (

=

/

) ground state electronic configuration [39]. Excited states are intrinsically better oxidants and reductants (larger reduction/oxidation potentials) than their corresponding ground states [41][42][43]; thus, the observed chemiluminescence opens the possibility that the RuBP-O

-Mn

—Rubisco excited state may be quenched via electron transfer. Consequently, the liberated reducing equivalent could participate in the reduction of NADP

to NADPH (

, blue pathway). In this way, oxidation of RuBP via O

may proceed in a spin-allowed manner, while the Mn

remains “innocent” in the generation of the oxygenated RuBP precursor. Mn

-centered redox may still proceed, with oxidation of excited Mn

to Mn

occurring in a manner independent of, but parallel to, substrate oxidation.

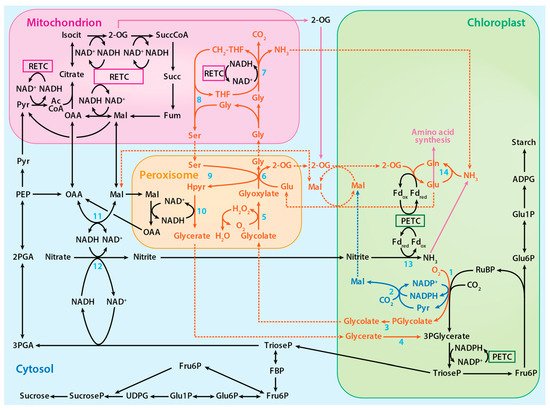

The proposed photorespiratory pathway within the context of photosynthetic carbon and nitrogen metabolism. The solid red lines represent reactions of the photorespiratory pathway, the solid blue lines represent reactions of the proposed alternative photorespiratory pathway, the solid purple lines represent reactions of amino acid synthesis, and the dotted lines represent associated transport processes. Numbered reactions are catalyzed by the following enzymes: 1. Rubisco, 2. Malic enzyme, 3. Phosphoglycolate phosphatase, 4. Glycerate kinase, 5. Glycolate oxidase, 6. Glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase, 7. Glycine decarboxylase complex, 8. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase-1, 9. Serine:glyoxylate aminotransferase, 10. Hydroxypyruvate reductase-1, 11. Malate dehydrogenase, 12, Nitrate reductase, 13 Nitrite reductase, and 14. Glutamine synthetase. PETC designates photosynthetic electron transport chain and RETC, respiratory electron transport chain. Adapted from ref. [8]. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature Ltd.

In wheat leaves, the ratio of Mn

to Mg

contents increased as the CO

levels increased and when the nitrogen source was nitrate rather than ammonium [32]. Nitrate assimilation into amino acids in shoots is heavily dependent on photorespiration, whereas ammonium assimilation is much less so. This indicates that plants shifted to Rubisco Mn

binding in order to compensate for the slower photorespiration rates and slower amino acid production that would otherwise occur under elevated CO

and nitrate nutrition.

2.3. The Photorespiratory Pathway

The 3-phosphoglycerate produced during photorespiration, like that produced during photosynthesis, is converted to triose phosphate and used to regenerate RuBP. On the other hand, 2-phosphoglycolate is converted to glycolate by phosphoglycolate phosphatase. In the peroxisome and mitochondrion, a series of reactions converts glycolate to glycerate, which is ultimately returned to the chloroplast to regenerate RuBP (

) [8]. In addition to Rubisco, several other chloroplast enzymes in the photorespiratory pathway, including malic enzyme and phosphoglycolate phosphatase, bind either Mg

or Mn

[8]. The plastid isoform of malic enzyme in

and tobacco catalyzes the reverse pyruvate synthesis reaction (pyruvate + CO

+ NADPH → malate + NADP) [44][45]. Phosphoglycolate phosphatase, which is responsible for the hydrolysis of 2-phosphoglycolate to glycolate, binds to and is activated by either metal [46]. Hypothesized is an alternative photorespiratory pathway that increases photorespiration energy efficiency by generating malate (RuBP + O

+ CO

+ H

O → glycolate + malate + 2Pi) when Mn

binds to these enzymes (

) [8].

3. Conclusions

Is photorespiration simply a futile cycle? The answer is “no”. Multiple lines of evidence show its crucial role in many plant processes. Despite heroic efforts to suppress photorespiration, disrupting any photorespiratory reaction usually proves detrimental to plants [139,140]. The reassimilation of COIs photorespiration simply a futile cycle? The answer is “no”. Multiple lines of evidence show its crucial role in many plant processes. Despite heroic efforts to suppress photorespiration, disrupting any photorespiratory reaction usually proves detrimental to plants [47][48]. The reassimilation of CO

2 from photorespiration [60] and the important role played by photorespiration in the acclimation of plants to conditions, such as salinity [141] and elevated COfrom photorespiration [49] and the important role played by photorespiration in the acclimation of plants to conditions, such as salinity [50] and elevated CO

2 [142], are topics that are beyond the scope of this review but nevertheless provide important evidence showing that photorespiration is not a wasteful process. There are many promising directions for further studies on photorespiration; for example, examining Mn[51], are topics that are beyond the scope of this review but nevertheless provide important evidence showing that photorespiration is not a wasteful process. There are many promising directions for further studies on photorespiration; for example, examining Mn

2+interactions with Rubisco, further exploring the reassimilation of photorespired CO

2, and exploring how the biochemical processes related to photorespiration contribute to its role in adaptation to various conditions will probably reveal that plant carbon fixation and respiration is more energy efficient than what has been previously assumed.

References

- Zelitch, I. Photorespiration: Studies with Whole Tissues. Photosynthesis II 1979, 28, 353–354.

- Canvin, D.T. Photorespiration: Comparison Between C3 and C4 Plants. Photosynthesis II 1979, 29, 368–396.

- Husic, D.W.; Husic, H.D.; Tolbert, N.E.; Black, C.C. The oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle or C2 cycle. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1987, 5, 45–99.

- Sharkey, T.D. Estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves. Physiol. Plant 1988, 73, 147–152.

- Ogren, W.L. Photorespiration: Pathways, Regulation, and Modification. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1984, 35, 415–442.

- Somerville, C.R.; Ogren, W.L. A phosphoglycolate phosphatase-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Nature 1979, 280, 833–836.

- Busch, F.A. Photorespiration in the context of Rubisco biochemistry, CO2 diffusion and metabolism. Plant J. 2020, 101, 919–939.

- Bloom, A.J.; Lancaster, K.M. Manganese binding to Rubisco could drive a photorespiratory pathway that increases the energy efficiency of photosynthesis. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 414–422.

- Bloom, A.J.; Smart, D.R.; Nguyen, D.T.; Searles, P.S. Nitrogen assimilation and growth of wheat under elevated carbon dioxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 1730–1735.

- McFadden, G.I. Origin and Evolution of Plastids and Photosynthesis in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016105.

- Raven, J.A. Rubisco: Still the most abundant protein of Earth? New Phytol. 2013, 198, 1–3.

- Badger, M.R.; Bek, E.J. Multiple Rubisco forms in proteobacteria: Their functional significance in relation to CO2 acquisition by the CBB cycle. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1525–1541.

- Kono, T.; Mehrotra, S.; Endo, C.; Kizu, N.; Matusda, M.; Kimura, H.; Mizohata, E.; Inoue, T.; Hasunuma, T.; Yokota, A.; et al. A RuBisCO-mediated carbon metabolic pathway in methanogenic archaea. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14007.

- Tabita, F.R.; Satagopan, S.; Hanson, T.E.; Kreel, N.E.; Scott, S.S. Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 1515–1524.

- Ogawa, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshizawa, R.; Kanno, K.; Makino, A. Effect of individual suppression of RBCS multigene family on Rubisco contents in rice leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 35, 546–553.

- Bracher, A.; Whitney, S.M.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Biogenesis and Metabolic Maintenance of Rubisco. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 68, 29–60.

- Aigner, H.; Wilson, R.H.; Bracher, A.; Calisse, L.; Bhat, J.Y.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Plant RuBisCo assembly in E. coli with five chloroplast chaperones including BSD2. Science 2017, 358, 1272–1278.

- Foyer, C.H.; Bloom, A.J.; Queval, G.; Noctor, G. Photorespiratory metabolism: Genes, mutants, energetics, and redox signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 455–484.

- Betti, M.; Bauwe, H.; Busch, F.A.; Fernie, A.R.; Keech, O.; Levey, M.; Ort, D.R.; Parry MA, J.; Sage, R.; Timm, S.; et al. Manipulating photorespiration to increase plant productivity: Recent advances and perspectives for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2977–2988.

- Walker, B.J.; VanLoocke, A.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Ort, D.R. The Costs of Photorespiration to Food Production Now and in the Future. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 107–129.

- Pierce, J.; Andrews, T.J.; Lorimer, G.H. Reaction intermediate partitioning by ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylases with differing substrate specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 10248–10256.

- Miziorko, H.M.; Sealy, R.C. Characterization of the ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase-carbon dioxide-divalent cation-carboxypentitol bisphosphate complex. Biochemistry 1980, 19, 1167–1171.

- Stec, B. Structural mechanism of RuBisCO activation by carbamylation of the active site lysine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18785–18790.

- Andrews, T.J.; Lorimer, G.H. The Biochemistry of Plants: A Comprehensive Treatise; Photosynthesis; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 10.

- Wildner, G.F.; Henkel, J. The effect of divalent metal ions on the activity of Mg(++) depleted ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate oxygenase. Planta 1979, 146, 223–228.

- Matsumura, H.; Mizohata, E.; Ishida, H.; Kogami, A.; Ueno, T.; Makino, A.; Inoue, T.; Yokota, A.; Mae, T.; Kai, Y. Crystal structure of rice Rubisco and implications for activation induced by positive effectors NADPH and 6-phosphogluconate. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 422, 75–86.

- Chollet, R.; Anderson, L.L. Regulation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase activities by temperature pretreatment and chloroplast metabolites. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1976, 176, 344–351.

- McCurry, S.D.; Pierce, J.; Tolbert, N.E.; Orme-Johnson, W.H. On the mechanism of effector-mediated activation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 6623–6628.

- Chu, D.K.; Bassham, J.A. Activation of ribulose 1,5-diphosphate carboxylase by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and other chloroplast metabolites. Plant Physiol. 1974, 54, 556–559.

- Hanson, T.E.; Satagopan, S.; Witte, B.H.; Kreel, N.E. Phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships of RubisCO and the RubisCO-like proteins and the functional lessons provided by diverse molecular forms. Philos. Trans R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 2629–2640.

- Tcherkez GG, B.; Farquhar, G.D.; Andrews, T.J. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7246–7251.

- Bloom, A.J.; Kameritsch, P. Relative association of Rubisco with manganese and magnesium as a regulatory mechanism in plants. Physiol. Plant 2017, 161, 545–559.

- Pierce, J.; Reddy, G.S. The sites for catalysis and activation of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase share a common domain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1986, 245, 483–493.

- Jordan, D.B.; Ogren, W.L. Species variation in kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1983, 227, 425–433.

- Martin, F.; Winspear, M.J.; MacFarlane, J.D.; Oaks, A. Effect of Methionine Sulfoximine on the Accumulation of Ammonia in C3 and C4 Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1983, 71, 177–181.

- Christeller, J.T. The effects of bivalent cations on ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Biochem. J. 1981, 193, 839–844.

- Christeller, J.T.; Laing, W.A. Effects of manganese ions and magnesium ions on the activity of soya-bean ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Biochem. J. 1979, 183, 747–750.

- Jordan, D.B.; Ogren, W.L. A Sensitive Assay Procedure for Simultaneous Determination of Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate Carboxylase and Oxygenase Activities. Plant Physiol. 1981, 67, 237–245.

- Lilley, R.M.; Wang, X.; Krausz, E.; Andrews, T.J. Complete spectra of the far-red chemiluminescence of the oxygenase reaction of Mn2+-activated ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase establish excited Mn2+ as the source. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16488–16493.

- Mogel, S.N.; McFadden, B.A. Chemiluminescence of the Mn2+-activated ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate oxygenase reaction: Evidence for singlet oxygen production. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 8333–8337.

- Bock, C.R.; Connor, J.A.; Gutierrez, A.R. Estimation of excited-state redox potentials by electron-transfer quenching. Application of electron-transfer theory to excited-state redox processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 4815–4824.

- Creutz, C.; Sutin, N. Reaction of tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(III) with hydroxide and its application in a solar energy storage system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 2858–2862.

- Sattler, W.; Ener, M.E.; Blakemore, J.D. Generation of powerful tungsten reductants by visible light excitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10614–10617.

- Müller, G.L.; Drincovich, M.F.; Andreo, C.S.; Lara, M.V. Nicotiana tabacum NADP-malic enzyme: Cloning, characterization and analysis of biological role. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 469–480.

- Wheeler MC, G.; Arias, C.L.; Tronconi, M.A.; Maurino, V.G.; Andreo, C.S.; Drincovitch, M.F. Arabidopsis thaliana NADP-malic enzyme isoforms: High degree of identity but clearly distinct properties. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 231–242.

- Husic, H.D.; Tolbert, N.E. Anion and divalent cation activation of phosphoglycolate phosphatase from leaves. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984, 229, 64–72.

- Timm, S.; Bauwe, H. The variety of photorespiratory phenotypes—Employing the current status for future research directions on photorespiration. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 737–747.

- Eisenhut, M.; Ruth, W.; Haimovich, M.; Bauwe, H.; Kaplan, A.; Hagemann, M. The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been conveyed endosymbiontically to plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17199–17204.

- Busch, F.A.; Sage, T.L.; Cousins, A.B.; Sage, R.F. C3 plants enhance rates of photosynthesis by reassimilating photorespired and respired CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 36, 200–212.

- Eisenhut, M.; Bräutigam, A.; Timm, S.; Florian, A.; Tohge, T. Photorespiration is crucial for dynamic response of photosynthetic metabolism and stomatal movement to altered CO2 availability. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 47–61.

- Ziotti, A.; Silva, B.P.; Neto, M. Photorespiration is crucial for salinity acclimation in castor bean. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 167, 103845.