Recent discoveries in the “omics” field and the growing focus on preventive health have opened new avenues for personalized nutrition (PN), which is becoming an important theme in the strategic plans of organizations that are active in healthcare, food, and nutrition research. PN holds great potential for individual health optimization, disease management, public health interventions, and product innovation. However, there are still multiple challenges to overcome before PN can be truly embraced by the public and healthcare stakeholders. The diagnosis and management of lactose intolerance (LI), a common condition with a strong inter-individual component, is explored as an interesting example for the potential role of these technologies and the challenges of PN. From the development of genetic and metabolomic LI diagnostic tests that can be carried out in the home, to advances in the understanding of LI pathology and individualized treatment optimization, PN in LI care has shown substantial progress. However, there are still many research gaps to address, including the understanding of epigenetic regulation of lactase expression and how lactose is metabolized by the gut microbiota, in order to achieve better LI detection and effective therapeutic interventions to reverse the potential health consequences of LI.

- lactose intolerance

- lactase persistence

- genetic testing

- polymorphisms

- epigenetic

- omics

- personalized nutrition

- dairy products

- functional foods

- Gut Microbiota

1. Introduction

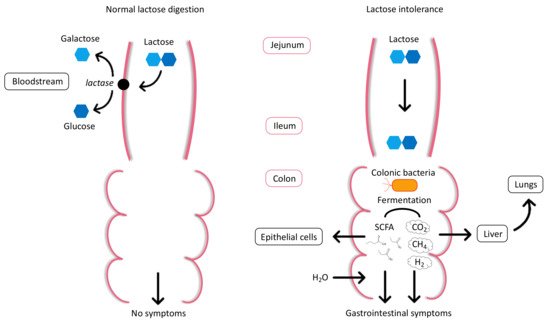

2. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Lactose Intolerance

3. Types of Lactose Intolerance

| Term | Definition |

|---|

| Lactose malabsorption | Failure to digest/absorb lactose due to primary or secondary lactase deficiency. |

| Lactose intolerance (LI) | Clinical syndrome in which the ingestion of lactose causes typical gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, nausea, abdominal pain, cramps. |

| Self-reported LI | Individuals who perceive themselves as being LI without medical diagnosis. |

| Lactase deficiency | Lack or absence of intestinal lactase enzyme activity. |

| Congenital lactase deficiency | Rare genetic disorder in which lactase is already absent at birth. |

| Primary lactase deficiency | Progressive decline of lactase enzyme activity with age. |

| Secondary lactase deficiency | Reversible condition caused by illness or injury of the small intestine and resulting in deficiency of intestinal lactase enzyme activity. |

| Lactase non-persistence (LNP) | Most common phenotype associated with lactase gene expression worldwide. Characterized by lactase activity decline during early childhood. |

| Lactase persistence (LP) | Phenotype expressed by the continued activity of the lactase enzyme throughout adulthood. |

4. Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance

5. Management of Lactose Intolerance

References

- Kaput, J.; Kussmann, M.; Radonjic, M.; Virgili, F.; Perozzi, G. Human nutrition, environment, and health. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10, 489.

- Walther, B.; Lett, A.M.; Bordoni, A.; Tomás-Cobos, L.; Nieto, J.A.; Dupont, D.; Danesi, F.; Shahar, D.R.; Echaniz, A.; Re, R.; et al. GutSelf: Interindividual Variability in the Processing of Dietary Compounds by the Human Gastrointestinal Tract. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900677.

- Ordovas, J.M.; Ferguson, L.R.; Tai, E.S.; Mathers, J.C. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ 2018, 361, bmj.k2173.

- Bush, C.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; El-Sohemy, A.; Minich, D.M.; Ordovás, J.M.; Reed, D.G.; Behm, V.A.Y. Toward the Definition of Personalized Nutrition: A Proposal by The American Nutrition Association. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 5–15.

- Mattar, R.; de Campos Mazo, D.F.; Carrilho, F.J. Lactose intolerance: Diagnosis, genetic, and clinical factors. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2012, 5, 113–121.

- Wiley, A.S. Lactose intolerance. Evol. Med. Public Health 2020, 2020, 47–48.

- Storhaug, C.L.; Fosse, S.K.; Fadnes, L.T. Country, regional, and global estimates for lactose malabsorption in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 738–746.

- Smith, G.D.; Lawlor, D.A.; Timpson, N.J.; Baban, J.; Kiessling, M.; Day, I.N.M.; Ebrahim, S. Lactase persistence-related genetic variant: Population substructure and health outcomes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 357–367.

- Comerford, K.B.; Pasin, G. Gene-Dairy Food Interactions and Health Outcomes: A Review of Nutrigenetic Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 710.

- Itan, Y.; Jones, B.L.; Ingram, C.J.; Swallow, D.M.; Thomas, M.G. A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 36.

- Tishkoff, S.A.; Reed, F.A.; Ranciaro, A.; Voight, B.F.; Babbitt, C.C.; Silverman, J.S.; Powell, K.; Mortensen, H.M.; Hirbo, J.B.; Osman, M.; et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 31–40.

- Luca, F.; Perry, G.H.; Di Rienzo, A. Evolutionary adaptations to dietary changes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 30, 291–314.

- Gerbault, P.; Liebert, A.; Itan, Y.; Powell, A.; Currat, M.; Burger, J.; Swallow, D.M.; Thomas, M.G. Evolution of lactase persistence: An example of human niche construction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 863–877.

- Itan, Y.; Powell, A.; Beaumont, M.A.; Burger, J.; Thomas, M.G. The origins of lactase persistence in Europe. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000491.

- Segurel, L.; Guarino-Vignon, P.; Marchi, N.; Lafosse, S.; Laurent, R.; Bon, C.; Fabre, A.; Hegay, T.; Heyer, E. Why and when was lactase persistence selected for? Insights from Central Asian herders and ancient DNA. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000742.

- Ségurel, L.; Bon, C. On the Evolution of Lactase Persistence in Humans. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2017, 18, 297–319.

- Lomer, M.C.; Parkes, G.C.; Sanderson, J.D. Review article: Lactose intolerance in clinical practice-myths and realities. Aliment. Pharmacol. 2008, 27, 93–103.

- Ingram, C.J.E.; Mulcare, C.A.; Itan, Y.; Thomas, M.G.; Swallow, D.M. Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence. Hum. Genet. 2009, 124, 579–591.

- Kuchay, R.A.H. New insights into the molecular basis of lactase non-persistence/persistence: A brief review. Drug Discov. Ther. 2020, 14, 1–7.

- Forsgård, R.A. Lactose digestion in humans: Intestinal lactase appears to be constitutive whereas the colonic microbiome is adaptable. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 273–279.

- Misselwitz, B.; Butter, M.; Verbeke, K.; Fox, M.R. Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management. Gut 2019, 68, 2080–2091.

- He, T.; Venema, K.; Priebe, M.G.; Welling, G.W.; Brummer, R.J.; Vonk, R.J. The role of colonic metabolism in lactose intolerance. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 38, 541–547.

- Deng, Y.; Misselwitz, B.; Dai, N.; Fox, M. Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8020–8035.

- Szilagyi, A. Adult lactose digestion status and effects on disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 29, 149–156.

- Swallow, D.M. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003, 37, 197–219.

- Ingram, C.J.; Elamin, M.F.; Mulcare, C.A.; Weale, M.E.; Tarekegn, A.; Raga, T.O.; Bekele, E.; Elamin, F.M.; Thomas, M.G.; Bradman, N.; et al. A novel polymorphism associated with lactose tolerance in Africa: Multiple causes for lactase persistence? Hum. Genet. 2007, 120, 779–788.

- Enattah, N.S.; Sahi, T.; Savilahti, E.; Terwilliger, J.D.; Peltonen, L.; Järvelä, I. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 233–237.

- Santonocito, C.; Scapaticci, M.; Guarino, D.; Annicchiarico, E.B.; Lisci, R.; Penitente, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Zuppi, C.; Capoluongo, E. Lactose intolerance genetic testing: Is it useful as routine screening? Results on 1426 south-central Italy patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 439, 14–17.

- Tomczonek-Moruś, J.; Wojtasik, A.; Zeman, K.; Smolarz, B.; Bąk-Romaniszyn, L. 13910C>T and 22018G>A LCT gene polymorphisms in diagnosing hypolactasia in children. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 210–216.

- Enattah, N.-S.; Kuokkanen, M.; Forsblom, C.; Natah, S.; Oksanen, A.; Jarvela, I.; Peltonen, L.; Savilahti, E. Correlation of intestinal disaccharidase activities with the C/T-13910 variant and age. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 3508–3512.

- Gugatschka, M.; Dobnig, H.; Fahrleitner-Pammer, A.; Pietschmann, P.; Kudlacek, S.; Strele, A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B. Molecularly-defined lactose malabsorption, milk consumption and anthropometric differences in adult males. Qjm 2005, 98, 857–863.

- Matthews, S.B.; Waud, J.P.; Roberts, A.G.; Campbell, A.K. Systemic lactose intolerance: A new perspective on an old problem. Postgrad Med. J. 2005, 81, 167–173.

- Troelsen, J.T. Adult-type hypolactasia and regulation of lactase expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1723, 19–32.

- Szilagyi, A.; Ishayek, N. Lactose Intolerance, Dairy Avoidance, and Treatment Options. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1994.

- Walsh, J.; Meyer, R.; Shah, N.; Quekett, J.; Fox, A.T. Differentiating milk allergy (IgE and non-IgE mediated) from lactose intolerance: Understanding the underlying mechanisms and presentations. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2016, 66, e609–e611.

- Mishkin, B.; Yalovsky, M.; Mishkin, S. Increased prevalence of lactose malabsorption in Crohn’s disease patients at low risk for lactose malabsorption based on ethnic origin. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 1148–1153.

- Szilagyi, A.; Galiatsatos, P.; Xue, X. Systematic review and meta-analysis of lactose digestion, its impact on intolerance and nutritional effects of dairy food restriction in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 67.

- Hasan, N.; Zainaldeen, M.; Almadhoob, F.; Yusuf, M.; Fredericks, S. Knowledge of lactose intolerance among clinicians. Gastroenterol. Insights 2018, 9.

- Martínez Vázquez, S.E.; Nogueira de Rojas, J.R.; Remes Troche, J.M.; Coss Adame, E.; Rivas Ruíz, R.; Uscanga Domínguez, L.F. The importance of lactose intolerance in individuals with gastrointestinal symptoms. Rev. Gastroenterol. México 2020, 85, 321–331.

- Lomer, M.C. Review article: The aetiology, diagnosis, mechanisms and clinical evidence for food intolerance. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 262–275.

- Lule, V.K.; Garg, S.; Tomar, S.K.; Khedkar, C.D.; Nalage, D.N. Food Intolerance: Lactose Intolerance. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 43–48.

- Di Rienzo, T.; D’Angelo, G.; D’Aversa, F.; Campanale, M.C.; Cesario, V.; Montalto, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ojetti, V. Lactose intolerance: From diagnosis to correct management. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17 (Suppl. 2), 18–25.

- Robles, L.; Priefer, R. Lactose Intolerance: What Your Breath Can Tell You. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 412.

- Law, D.; Conklin, J.; Pimentel, M. Lactose intolerance and the role of the lactose breath test. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1726–1728.

- Usai-Satta, P.; Scarpa, M.; Oppia, F.; Cabras, F. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: What should be the best clinical management? World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 3, 29–33.

- Furnari, M.; Bonfanti, D.; Parodi, A.; Franzè, J.; Savarino, E.; Bruzzone, L.; Moscatelli, A.; Di Mario, F.; Dulbecco, P.; Savarino, V. A comparison between lactose breath test and quick test on duodenal biopsies for diagnosing lactase deficiency in patients with self-reported lactose intolerance. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 47, 148–152.

- Hovde, Ø.; Farup, P.G. A comparison of diagnostic tests for lactose malabsorption—Which one is the best? BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 82.

- Aragón, J.J.; Hermida, C.; Martínez-Costa, O.H.; Sánchez, V.; Martín, I.; Sánchez, J.J.; Codoceo, R.; Cano, J.M.; Cano, A.; Crespo, L.; et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of hypolactasia with 4-Galactosylxylose (Gaxilose): A multicentre, open-label, phase IIB-III nonrandomized trial. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 29–36.

- Domínguez Jiménez, J.L.; Fernández Suárez, A.; Muñoz Colmenero, A.; Fatela Cantillo, D.; López Pelayo, I. Primary hypolactasia diagnosis: Comparison between the gaxilose test, shortened lactose tolerance test, and clinical parameters corresponding to the C/T-13910 polymorphism. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 471–476.

- Bayless, T.M.; Brown, E.; Paige, D.M. Lactase Non-persistence and Lactose Intolerance. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 19, 23.

- Gille, D.; Walther, B.; Badertscher, R.; Bosshart, A.; Brügger, C.; Brühlhart, M.; Gauch, R.; Noth, P.; Vergères, G.; Egger, L. Detection of lactose in products with low lactose content. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 83, 17–19.

- Dekker, P.J.T.; Koenders, D.; Bruins, M.J. Lactose-Free Dairy Products: Market Developments, Production, Nutrition and Health Benefits. Nutrients 2019, 11, 551.

- Facioni, M.S.; Raspini, B.; Pivari, F.; Dogliotti, E.; Cena, H. Nutritional management of lactose intolerance: The importance of diet and food labelling. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 260.

- McSweeney, P.L.H. Biochemistry of cheese ripening. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2004, 57, 127–144.

- Savaiano, D.A. Lactose digestion from yogurt: Mechanism and relevance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1251s–1255s.

- Van der Merwe, J.; Steenekamp, J.; Steyn, D.; Hamman, J. The Role of Functional Excipients in Solid Oral Dosage Forms to Overcome Poor Drug Dissolution and Bioavailability. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 393.

- Mill, D.; Dawson, J.; Johnson, J.L. Managing acute pain in patients who report lactose intolerance: The safety of an old excipient re-examined. Adv. Drug Saf. 2018, 9, 227–235.

- Sethi, S.; Tyagi, S.K.; Anurag, R.K. Plant-based milk alternatives an emerging segment of functional beverages: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3408–3423.

- Harju, M.; Kallioinen, H.; Tossavainen, O. Lactose hydrolysis and other conversions in dairy products: Technological aspects. Int. Dairy J. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 22.

- Vyas, H.K.; Tong, P.S. Process for Calcium Retention During Skim Milk Ultrafiltration. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 2761–2766.

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Eaton, T.K.; Sermet, O.M.; Savaiano, D.A. Milk Containing A2 β-Casein ONLY, as a Single Meal, Causes Fewer Symptoms of Lactose Intolerance than Milk Containing A1 and A2 β-Caseins in Subjects with Lactose Maldigestion and Intolerance: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3855.

- Jianqin, S.; Leiming, X.; Lu, X.; Yelland, G.W.; Ni, J.; Clarke, A.J. Effects of milk containing only A2 beta casein versus milk containing both A1 and A2 beta casein proteins on gastrointestinal physiology, symptoms of discomfort, and cognitive behavior of people with self-reported intolerance to traditional cows’ milk. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 35.

- Suri, S.; Kumar, V.; Prasad, R.; Tanwar, B.; Goyal, A.; Kaur, S.; Gat, Y.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, J.; Singh, D. Considerations for development of lactose-free food. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2019, 15, 27–34.

- Montalto, M.; Nucera, G.; Santoro, L.; Curigliano, V.; Vastola, M.; Covino, M.; Cuoco, L.; Manna, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Effect of exogenous beta-galactosidase in patients with lactose malabsorption and intolerance: A crossover double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 489–493.

- Montalto, M.; Curigliano, V.; Santoro, L.; Vastola, M.; Cammarota, G.; Manna, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Management and treatment of lactose malabsorption. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 187–191.