Inoculants or biofertilizers aiming to partially or fully replace chemical fertilizers are becoming increasingly important in agriculture, as there is a global perception of the need to increase sustainability.

- rhizobia

- plant-growth-promoting bacteria

- fungicide

- insecticide

- herbicide

- biological nitrogen fixation

- inoculation

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Technologies and agricultural inputs currently applied for food production are essential for large-scale production and are mandatory to feed a population of more than 7 billion people [1]. Years of research and experiments continually performed into the challenges and technological evolution have resulted in progress in several fields of science. The 1950s was known as the “Green Revolution” period, marked by the intense modernization of agriculture [2][3]. Products including new machines and synthetic fertilizers, with an emphasis on nitrogen (N) fertilizers, pesticides, seeds of better quality, improvements in the water supply systems, breeding and genetic engineering are examples of technologies developed at that time and that have gained prominence in agriculture [4][5].

The main positive result of the Green Revolution was the global increase in food production, thus contributing to the reduction of hunger in the world. However, in the following years, the side-effect of this revolution unfolded [6]. The accumulation of pesticides and chemical fertilizers contributes to the pollution of groundwater and cultivated land, soil degradation, and reduction of biodiversity in different ecosystems [5][7]. Increased deforestation, soil degradation, and emission of polluting gases into the atmosphere have been increasingly observed [8][9][10]. Despite the undeniable benefits of the Green Revolution, many of the technologies and inputs generated during that period are broadly criticized today. Currently, efforts are being made towards the development of new technologies and inputs focused on more sustainable systems.

Contemporary scientists have pointed out that we are living in a “New Green Revolution” whose main characteristic, and which differs from that experienced in the 1950s, is the development of environmentally-friendly technologies and products [3][11][12][13]. Examples of this new concept include the development of products and techniques such as crop rotation, plant genetic engineering for resistance to pests, diseases, and abiotic stresses such as drought, the use of bio-inputs as activators of soil biota, biopesticides and microbial inoculants, also known as biofertilizers in some countries, with the purpose of partially or fully replacing the use of chemical fertilizers, favoring the growth of plants [14][15][16][17].

Although the current movement towards agricultural sustainability has force worldwide, the use of agrochemicals is and will continue to be the reality of most farmers [18]. As such, the common scenario towards improving agricultural sustainability with feasible yields to guarantee food security includes the increasing use of bioproducts, such as microbial inoculants, together with pesticides, which are still indispensable for controlling pests and diseases [4][5][11][14][17]. Therefore, the compatibility between inoculants and pesticides must be understood.

In general, pesticides contain molecules that are potentially toxic to living cells. Depending on the specificity, pesticides can cause toxicity to cells of microorganisms, animals, and plants, often resulting in death after contact with the product. In agriculture, they are commonly applied to the seeds, soil, and leaves of plants to prevent or control pests and diseases [7][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]. Usually, at least for large commercial crops such as is the case of soybean [

Glycine max (L.) Merr.] [11][15][17][20] and maize (

Zea mays L.) [26][27][28] in South America, pesticides and inoculants are added together on the seeds. Thus, it is necessary to verify whether microbial cells in the inoculants are affected by pesticides, impairing the benefits of inoculation.

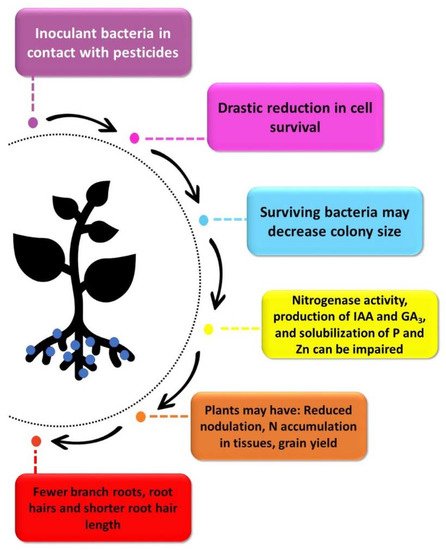

We should also mention the increasing demand for anticipated inoculation or pre-inoculation [20], and in the pre-inoculation the most common adoption is to treat seeds with pesticides and inoculants several days before sowing [15][24]. However, the microorganisms are subjected to long-term exposure to pesticides, increasing the pernicious effect on the bacteria and resulting, for example, in decreased nodulation in legumes [21][22][23], lower N accumulation in grains [24][25], and negatively impacting root development of grasses [26]. These losses may be due to microbial cell death caused by pesticides, as demonstrated in some studies [25][26][27][28], in which the longer the contact between bacteria and pesticides, the greater the mortality. Moreover, changes in cell metabolism, such as formation of smaller colonies and decreased nitrogenase activity, have been reported [25].

2. Are Pesticides and Microbial Inoculants Compatible?

Rhizobium

Bradyrhizobium

Azospirillum

2.1. Compatibility with Fungicides

Fungicides are chemical products formulated to prevent the infection of plant tissues by phytopathogenic fungi, and in some cases, capable of extending the control of diseases caused by bacteria and viruses. The control exerted by fungicides can be mediated by killing the pathogen, temporarily inhibiting its germination and growth, or by affecting the production of spores [32]. Over the years, several fungicides have made it to the market; some have stood out and remained at the top in the list of the most used fungicides until today, more effective products have replaced others, and some have been banned. Fungicides of contact generally do not have a specific mode of action, are highly toxic, and when applied to seeds, soil, and plant leaves limit the pathogen survival. The most common are thiram (dithiocarbamate), captan (quinone and heterocyclic), exon (aromatic), and guazatine. Upon entering microbial cells, the molecules promote a series of chemical reactions in nucleic acids and their precursors, and metabolic routes, affecting cell survival [32].

2 fixation efficiency; in general, studies have been performed with soybean (e.g., [33][34][35][36]). The use of pesticides intensified in the past two decades, and so did concerns about their compatibility with inoculants [17].

−1

B. japonicum

−1 reduced nodule number and dry weight, as well as the activity of the bacterial enzyme nitrogenase, responsible for the nitrogen fixation process. Similarly, there are reports [24][37] of decrease in soybean nodulation and N accumulation in plants when seeds were inoculated with

B. elkanii

B. japonicum (SEMIA 5079) and treated with different fungicides, benomyl, captan, carbendazin, carboxin, difenoconazole, thiabendazole, thiram, and tolylfluanid. Changes in nodule number were also observed in a field trial by Zilli et al. [38] when soybean seeds were treated with either carbendazin + thiram or carboxin + thiram.

B. elkanii

Bradyrhizobium

B. elkanii

B. japonicum

B. diazoefficiens (SEMIA 5080)] [38]. In another study, Gomes et al. [39] observed no effects on nodulation when seeds were inoculated with

B. japonicum

B. diazoefficiens

B. japonicum

B. elkanii

®

B. elkanii

B. elkanii

B. japonicum

B. diazoefficiens

It is reasonable to postulate that the main effects of the fungicides used in seed treatment would be the decrease of rhizobial survival or inhibition of the root infection process, consequently affecting nodulation and BNF, and as a result grain yield, as observed by Zilli et al. [38]. In that study, the grain yield reduced by 20%, in addition to a decrease in the N content in grains when seeds were treated with

B. elkanii

Figure 2). However, some reports have indicated that the effects of fungicides may appear later. For example, in a study by Gomes et al. [39], although fungicides (carbendazin + thiram) did not affect nodulation, plants had lower number of pods per plant, grains per plant, and yield. Intriguingly, in two field experiments performed with soybean in Brazil, seed treatment with Standak

® Top affected the total N accumulated in the grains of plants relying on both BNF and N fertilizer, indicating the negative impact of the pesticide on N metabolism [25]. In another study, a decrease in both protein and oleic acid contents was observed in soybean inoculated and treated with mefenoxan + fludioxonil [40].

Figure 2.

As mentioned previously, negative effects may be related to the toxicity of fungicides on microbial cells, followed by impacts on microbial metabolism, reducing the effectiveness of the inoculant. Ahmed et al. [41] evaluated the growth of

Bradyrhizobium

Rhizobium

−1

−1

Figure 2). Rathjen et al. [42] also reported that

Rhizobium leguminosarum

−1

B. elkanii

B. japonicum

A. brasilense

Table 1.

| Pesticide | Concentration | Microorganism | Effect | Reference | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocrotophos | i | , Malathion | i | , Chlorpyripho | i | , Dichlorvos | i | , Lindano | i | e Endosulphan | i | Recommended dose of each product | Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus | With the exception of Malathion, all insecticides reduced cell viability. Nitrogenase activity was totally inhibited by Monocrotophos, Dichlorvos and Lindano. Production of IAA and GA | 3 | , and solubilization of P and Zn were impaired | [43] | [106] |

| Butachlor | h | , Alachlor | h | Atrazine | h | and 2,4-D | h | Recommended dose of each product | Cell growth was hindered by 2,4-D. All herbicides reduced the activity of nitrogenase, the production of IAA and GA | 3, | and the solubilization of P and Zn |

]. Souza and Guedes [47] gathered studies on the action of several herbicides on

Allium cepa

Vicia faba

Examples of herbicides applied worldwide include glyphosate, paraquat, and diuron. Among these, the most well-known is glyphosate; since its introduction in the 1970s, its use spread quickly, facilitated cropping, but also implied in the growing appearance of resistant weeds, resulting from a natural process of plant adaptation, and decreasing its efficacy [48][49][50]. An important alternative to minimize this problem, in addition to integration with other control methods, would be diversification in the use of herbicides, including others with different mechanisms of action [51].

Few studies have investigated the compatibility between herbicides and inoculants. Madhaiyan et al. [43] evaluated the effects of different herbicides (butachlor, alachlor, atrazine, and 2,4-D) in liquid culture medium on the growth and metabolism of

G. diazotrophicus

3

3

G. diazotrophicus [43].

In an assay performed under greenhouse conditions, Angelini et al. [52] evaluated the effects of imazetapir, imazapic, S-metachlor, diclosulam, and glyphosate on diazotrophic bacteria in the soil during the cultivation of peanuts (

Arachis hypogaea L.). The seeds were sown and the herbicide was sprayed on the soil surface. All herbicides caused reduction in cell concentration in both free and symbiotic diazotrophic bacteria, and this negative impact was confirmed under field conditions even one year after the application. Nitrogenase activity also reduced due to herbicides, except for glyphosate [52] (

Table 2.

| Culture | Fungicide | Microorganism | local | Effect | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean ( | Glycine max | ) | Thiram | f | B. japonicum | Greenhouse | Lower nodule number, nodule dry weight and nitrogenase activity | [21] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Benomyl | f | , Captan | f | , Carbendazin | f | , Carboxin | f | , Difenoconazole | f | , Thiabendazole | f | , Thiram, Tolylfluanid | f | B. elkanii | (strain SEMIA 5019) + | B. japonicum | (strain SEMIA 5079) | Greenhouse and field | Reduction in the number of nodules and in the total N in grains | [24] | ||||||||||

| Captan | f | , Thiram | f | , Luxan | f | and Fernasan-D | f | 1000 µg L | −1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbendazin | f | + Thiram | f | ; Carboxin | f | + Thiram | f | B. elkanii | (strains 5019 + 587), | B. japonicum | (strain 5079) + | B. diazoefficiens | (strain SEMIA 5080) | Bradyrhizobium | sp. and | Rhizobium | sp. | Decreased colony diameter and inhibited growth in areas close to the fungicide application site | [41] | [104] | ||||||||||

| Field | Reduction of nodulation efficiency. Reduction of N content and grain yield to SEMIA 587 with Carbendazin + Thiram | [ | 38 | ] | [101] | Benomyl | f | , Captan | f | , Carbendazin | f | , Carboxin | ||||||||||||||||||

| Carbendazin | f | + Thiram | ff | , Difenoconazole | f | , Thiabendazole | f | , Thiram | f | , Tolylfluanid | f | Recommended dose for soybean | B. japonicum | (strain 5079) + | B. diazoefficiensB. elkanii | and | B. japonicum | All fungicides caused mortality of microorganisms | (strain SEMIA 5080)[24] | |||||||||||

| Field | Reduction in the number of pods per plant and grains per plant | [ | 39 | ] | [102] | Imidacloprid | i | , Fipronil | i | , Thiamethoxam | i | , Endosulphan | i | e Carbofuran | i | 250 g ha | −1 | , 400 g ha | −1 | , 480 g ha | −1 | , 2.800 g ha | −1 | , 1.650 g ha | −1 | , respectively | Herbaspirillum seropedicae | Endosulphan increased the lag phase. Carbofuran increased generation time and reduced lag phase | [44] | [107] |

| Pyraclostrobin | f | , thiophanato-methyl | f | e fipronil | i | 2 mL kg | −1 | maize seed | A. brasilense | (strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6) | Drastic reduction in cell concentration 24 h after inoculation in treated seeds | [26] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Carbendazin | f | + Thiram | f | 40–60 mL 20 kg | −1 | maize seed | Drastic reduction in cell concentration 24 h after inoculation in treated seeds | [27] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| metalaxil-m + fludioxonil + tiametoxame + abamectin | Recommended dose for maize | Drastic reduction in cell concentration 12 h after inoculation in treated seeds | [28] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thiram | f | , Thiram + Thiabendazole | f | and PPT | f | >200 µg L | −1 | Rhizobium leguminosarum | bv. viciae | Formation of growth inhibition halos greater than 10 mm around the fungicide | [42] | [105] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Imidacloprid | i | 0, 100, 200 e 300 µg L | −1 | Formation of growth inhibition halos greater than 10 mm around the insecticide for all concentrations evaluated | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pyraclostrobin | f | , thiophanato-methyl | f | e fipronil | i | Recommended dose for soybean | B. elkanii | and | B. japonicum | Drastic decrease in cell concentration after 7 days of exposure. Colony formation with smaller diameter | Rodrigues et al. [25] |

2.2. Compatibility with Insecticides

Many herbivorous insects feed on plants during their larval and adult stages, and/or some are important vectors of plant diseases. In both cases, insects may cause serious damages to crops. Insecticides, usually synthetic chemicals, acting as ovicidal, larvicidal, and adulticidal agents are used to prevent growth or kill insects [45]. Neonicotinoids, organophosphates, diamides, pyrethroids, and carbamates act on nerves and muscles; phosphides, cyanides, and carboxamides on respiration, and cyclic ketoenols and ecdysone are agonists that interfere with insect growth and development [46].

Rathjen et al. [42] evaluated the in vitro toxicity of an imidacloprid-based insecticide on

R. leguminosarum

Mesorhizobium ciceri

−1

R. leguminosarum

Medicago sativa

Ensifer

Sinorhizobium

meliloti

−1

Cicer arietinum

Pisum sativum

Vigna radiata

Lens esculentus, = Lens culinaris

Insecticides also affect PGPB other than rhizobia. For example, Fernandes et al. [44] studied the effects of five insecticides (imidacloprid, fipronil, fenamethoxam, endosulfan, and carbofuran) indicated for sugarcane (

Saccharum

Herbaspirillum seropedicae. In vitro evaluations of cell growth after 33 h indicated that the insecticides that most interfered with bacterial growth were endosulfan and carbofuran. Madhaiyan et al. [43] evaluated the effect of different insecticides (monocrotophos, malathion, chlorpyriphos, diclorvos, lindane and endosulfan) on

Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus

G. diazotrophicus

3, respectively. The authors also described that the insecticides dichlorvos, chlorpyriphos, and lindane completely inhibited the solubilization of phosphate (P) and zinc (Zn) [43] (

2.3. Compatibility with Herbicides

Another class of important pesticides for agriculture are herbicides used for weed control. Herbicides have different degrees of specificity based on differences in biochemical pathways in certain plant groups. The mode of action of herbicides has specific degrees of toxicity, depending on the biochemical differences of the plants, and is generally related to the cell division process [47

| Mefenoxam | ||||||||||||||||||

| f | ||||||||||||||||||

| + Fludioxonil | ||||||||||||||||||

| f | B. japonicum | Field | Reduced grain yield and protein and oleic acid content | [40] | [103] | |||||||||||||

| Pyraclostrobin | f | , thiophanato-methyl | f | and fipronil | i | B. japonicum | (strain 5079) and | B. diazoefficiens | (strain 5080) | Field | Less N accumulation in grains | [25] | ||||||

| Alfafa ( | Medicago sativa) | Methyl parathion | i | , DDT | i | e pentachlorophenol | i | Sinorhizobium meliloti | , | Greenhouse | Reduction of nitrogenase activity, number of nodules and plant dry weight | [22] | ||||||

| Peanut ( | Arachis | hypogaea). | Imazetapir | h | , Imazapic | h | , S-metachloro | h | , Dichlosulam | h | and Glyphosate | h | Diazotrophic bacteria present in the soil | Greenhouse | Reduction of cell concentration of free and symbiotic diazotrophic bacteria | [52] | [115] | |

| Field | Reduced cell concentration of free and symbiotic diazotrophic bacteria and reduced nitrogenase activity except for glyphosate | |||||||||||||||||

| Chickpeas ( | Cicer arietinum | L.), pea ( | Pisum sativum | L.), Mung beans ( | Vigna radiata | L. Wiclzek) and lentil ( | Lens esculentus | , = | Lens culinaris | Medik). | Pyriproxyfen | i | Bacteria commonly present in the soil used | Pots in the field | Reduction in the number of nodules, in the dry weight of nodules, in the concentration of N in roots and in protein concentration in the grains | [23] | ||

| Rice ( | Oryza sativa | ) | Benthicarb | h | Cyanobacteria naturally found in the rice paddy soil | Field | Decreased cell growth, nitrogenase activity and Naccumulation | [53] | [116] | |||||||||

| Maize ( | Zea mays | ) | Pyraclostrobin | f | , thyophanato-methyl | f | and fipronil | i | A. brasilense | (strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6) | Greenhouse | Fewer branch roots, root hair and shorter root hair length | [26] |

The ability of cyanobacteria to fix atmospheric nitrogen in flooded soils suitable for rice cultivation make this group an important ally in maintaining soil fertility and contributing to cereal yield. Thus, Dash et al. [53] evaluated the responses of cyanobacteria in rice plantation soil to the exposure of different agrochemicals, including the herbicide benthiocarb that was applied in one dose at the time of puddling. The herbicide decreased cell growth, which was even worse when combined with urea (used as a fertilizer). Benthiocarb reduced nitrogenase activity by between 13–27%, compared with the control without herbicide, and its combination with urea resulted in an even greater reduction in addition to a decrease in the nitrogen accumulation that reached 47% at 60 days.

Concerning the symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia, in general, herbicides have been considered less toxic than fungicides and insecticides [37], with glyphosate being the one with lower toxicity [54][55]. Although the negative effects of glyphosate on

B. japonicum growth were reported by King et al. [56], the doses in the experiment were far higher than those recommended for field application. With the release of genetically modified (GM) genotypes tolerant of herbicides, studies on the compatibility with the GM genotypes and herbicides have begun. In soybean, which represents the most used herbicide-tolerant species, glyphosate-resistant (Roundup Ready) pairs of nearly isogenic cultivars were evaluated in six field sites in Brazil for three crop seasons. Although the transgenic trait negatively affected some BNF variables, these effects had no significant impact on soybean grain yield, and no consistent differences between glyphosate and conventional herbicide application were observed on BNF-associated parameters [57]. Similar results were reported in 20 field trials performed with soybean with the

ahas transgene, imidazolinone, and conventional herbicides [58]. However, it is worth mentioning that with the increasing doses of the herbicides, BNF can be reduced, especially under abiotic stressing conditions, as shown for glyphosate in soybean [59][60]. Interestingly, it has been long shown that several members of the family Rhizobiaceae were able to degrade glyphosate [61], ability that has been few explored, but that it can contribute to decrease the toxicity effects. Indeed, the search for indigenous and engineered microorganisms, used as isolated microbial species or microbial consortia can result in the complete mineralization of herbicides such as atrazine [62].

2.4. Compatibility with Mixtures (Fungicides, Insecticides, and Herbicides)

Approximately 70% of the pesticides available in the market contain mixtures of two or more types of fungicides and insecticides [63] and are often combined with herbicides at the time of application, aiming to facilitate the combined control of pests, diseases, and weeds. However, the damage to microbial inoculants increases with the number of combined chemicals. As previously mentioned, Standak

®

B. japonicum

B. elkanii

® Top for up to 90 days, often resulting in zero recoveries of rhizobial cells from seeds [63].

®

A. brasilense

5

2

−1

®

A. brasilense