This review presents the common commercially available skin substitutes and their clinical use. Moreover, the choice of an appropriate hydrogel type to prepare cell-laden skin substitutes is discussed. Additionally, we present recent advances in the field of bioengineered human skin substitutes using three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting techniques. Finally, we discuss different skin substitute developments to meet different criteria for optimal wound healing.

1. Introduction

Skin is the largest organ and protects the human body against the external environment [1]. Loss of the integrity of the skin barrier, as a result of injury or malformation may lead to major complications or even death. Therefore, wound healing represents a crucial ability of the human skin to repair any skin defect and to keep proper skin homeostasis.

Large and deep skin wounds caused by extensive burns or tissue trauma still pose a significant challenge for the surgeon. If those wounds do not heal in time after skin damage, they might cause infection or life-threatening complications. [2]. Therefore, it is pivotal to develop tissue-regenerating biomaterials with high biological activity. Accordingly, the ideal skin substitute should have good biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, proper hydrophilicity, and biodegradability [3].

2. Skin Injuries and Common Treatment Techniques

The human skin consists of three major components including a superficial epidermis, a dermis, and a hypodermis [4]. The epidermis is composed of several layers. The outermost layer contains dead cells, which shed periodically and are continually replaced by cells derived from the basal layer [5]. The dermis connects the epidermis to the hypodermis layer, and due to the high content of collagen and elastin fibers, the dermis gives skin its strength and elasticity [6]. The hypodermis is the deepest layer of the skin located underneath the dermis. The hypodermis consists mainly of adipocytes, which accumulate fat. It also plays a role in thermoregulation, protection and provides insulation and cushioning for the integument [7].

The integrity of skin can be disrupted by various factors, leading to different types of wounds including acute and chronic wounds. Furthermore, wounds can be further split into mechanical injuries such as those caused by external factors (abrasions and tears) and skin injuries raised from radiation, electricity, corrosive chemicals, and thermal sources causing severe burns [8].

Skin wound healing is a complex, multi-stage process, which can be divided into homeostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (maturation) phases [1]. To facilitate skin repair, the fine-tuned activation of numerous cell types such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells is required. Furthermore, these cells secrete a variety of proinflammatory mediators, growth factors, and cytokines that promote skin repair [2]. Among immune cells, macrophages appear to be pivotal in this process [9][10][11]. They appear early during wound healing as so-called M1-polarized macrophages and differentiate to M2-phenotype at later stages of skin wound healing [12][13]. The phenotype change from M1 to M2 seems to be crucial to support the appropriate wound healing process. In contrast, prolonged M1-macrophage persistence in the wound might results in enhanced inflammation, leading to excessive scarring and delayed wound healing [11][14].

Skin wound healing is a complex, multi-stage process, which can be divided into homeostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (maturation) phases [1]. To facilitate skin repair, the fine-tuned activation of numerous cell types such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells is required. Furthermore, these cells secrete a variety of proinflammatory mediators, growth factors, and cytokines that promote skin repair [2]. Among immune cells, macrophages appear to be pivotal in this process [9,10,11]. They appear early during wound healing as so-called M1-polarized macrophages and differentiate to M2-phenotype at later stages of skin wound healing [12,13]. The phenotype change from M1 to M2 seems to be crucial to support the appropriate wound healing process. In contrast, prolonged M1-macrophage persistence in the wound might results in enhanced inflammation, leading to excessive scarring and delayed wound healing [11,14].

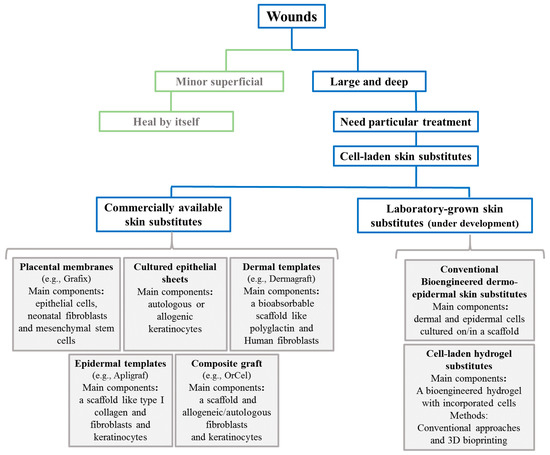

The human body is capable of healing minor superficial skin injuries by epithelialization without any particular treatment. However, large and deep skin defects require skin substitution to heal properly [15].

In particular, non-healing chronic wounds impose an immense financial burden on the healthcare systems and societies [2]. The primary reason for the impaired healing of chronic wounds is repeated tissue insults or accompanying diseases such as diabetes [16]. Moreover, in hard-to-heal chronic wounds, impaired vascularization is the main cause of delayed healing that might lead to tissue necrosis and, eventually, amputation [13][17]. In fact, capillaries are responsible for the metabolic exchange between blood and tissues [18][19]. If the angiogenesis process is disturbed, the wound cannot heal properly and the healing period is prolonged [18][19]. Thus, rapid neovascularization within only days after skin substitute implantation is of vital importance for the efficient healing of those wounds [12][13][18][20][21][22][23].

In particular, non-healing chronic wounds impose an immense financial burden on the healthcare systems and societies [2]. The primary reason for the impaired healing of chronic wounds is repeated tissue insults or accompanying diseases such as diabetes [16]. Moreover, in hard-to-heal chronic wounds, impaired vascularization is the main cause of delayed healing that might lead to tissue necrosis and, eventually, amputation [13,17]. In fact, capillaries are responsible for the metabolic exchange between blood and tissues [18,19]. If the angiogenesis process is disturbed, the wound cannot heal properly and the healing period is prolonged [18,19]. Thus, rapid neovascularization within only days after skin substitute implantation is of vital importance for the efficient healing of those wounds [12,13,18,20,21,22,23].

3. Cell-Based Skin Substitutes

Chronic wounds influence a patient’s life quality, leading to impaired mobility, sleep disturbance, psychological stress, and chronic pain [24]. A central problem causing poor skin wound healing in chronic wounds is impaired vascularization and cell activity [25]. Therefore, progress in the tissue engineering field aims for the development of cell-based wound substitutes or wound coverages that improve wound healing by promoting cell migration, differentiation, and vascularization [24]. The majority of cell-based skin substitutes are comprised of a scaffold upon which cells are seeded/cultured. Scaffolds are designed to integrate into the host tissue and provide an appropriate environment for cell growth, infiltration, and differentiation [26]. Thus, those scaffolds need to exhibit some specific characteristics such as appropriate porosity distribution to deliver oxygen and nutrients to cells and drive out carbon dioxide and waste products to allow cell proliferation, and expansion and biocompatibility. Moreover, the scaffold should mimic the mechanical properties of native human skin, which has an elastic modulus in the range of 88–300 kPa [27]. Accordingly, different skin templates have been engineered worldwide and there are various commercial cell-based templates for wound healing applications. demonstrates a classification and summary of commercial skin substitutes with examples discussed in this review.

Figure 1.

A schematic classification and summary of different commercial and bioengineered skin substitutes for large and hard-to-heal wounds.