Insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed metalloprotease that degrades insulin and several other intermediate-size peptides. For many decades, IDE had been assumed to be involved primarily in hepatic insulin clearance, a key process that regulates availability of circulating insulin levels for peripheral tissues. Emerging evidence, however, suggests that IDE has several other important physiological functions relevant to glucose and insulin homeostasis, including the regulation of insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. Investigation of mice with tissue-specific genetic deletion of Ide in the liver and pancreatic β-cells (L-IDE-KO and B-IDE-KO mice, respectively) has revealed additional roles for IDE in the regulation of hepatic insulin action and sensitivity.

- insulin-degrading enzyme

- insulin resistance

- pancreas

- liver

- insulin receptor

- glucose transporters

1. Introduction

Insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE; EC 3.4.24.56; a.k.a. insulin protease, insulinase, insulysin, insulin-glucagon protease, neutral thiol protease, metalloendoprotease, amyloid-degrading protease or peroxisomal protease) is a neutral Zn2+ metallo-endopeptidase that is ubiquitously expressed in insulin-responsive and non-responsive cells [1,2][1][2]. IDE belongs to a distinct superfamily of zinc-metalloproteases (clan M16) sometimes called “inverzincins” because they are characterized by a zinc-binding consensus sequence (HxxEH) that is inverted with respect to the sequence in most conventional metalloprotease (HExxH) [1,3,4][1][3][4]. IDE and its homologues represent an interesting example of convergent evolution; despite independent origins, IDE shares striking structural and functional similarity with conventional metalloproteases (clan M13 family; e.g., thermolysin and neprilysin) [3,4,5][3][4][5].

IDE and its homologs and paralogs are highly conserved and present in phylogenetically diverse organisms, ranging from viruses to humans [6], highlighting the fact that IDE is a multifunctional protein with proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions. Human IDE shares significant sequence similarity with orthologs in bacteria and yeast, for example, including the HxxEH zinc-binding motif. The protease has insulin-binding and -degrading activity in Neurospora crassa, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Escherichia coli (E. coli protease III or pitrilysin) [7,8,9,10][7][8][9][10]. IDE orthologs exhibit a periplasmic localization in E. coli [11] [11] and A. calcoaceticus [9], whereas the ortholog in N. crassa is membrane bound, leading to a proposed function as a putative insulin receptor (IR) [7]. Of interest, the yeast IDE homologues Axl1p and Ste23 are incapable of degrading insulin despite possessing the conserved zinc-binding motif [12]. The proteolytic activity of Ste23 is required, however, for N-terminal cleavage of the pro-a-factor, the precursor of a pheromone (a-factor) involved in the mating response of haploid yeast cells [13]. Interestingly, rat IDE can promote the formation of mature a-factor in vivo, suggesting that the functional conservation of IDE, Axl1p and Ste23 may be not be bidirectionally conserved [12]. Humans and other mammals also express several IDE paralogs, including N-arginine dibasic convertase (a.k.a., nardilysin), a cytosolic, secreted and membrane bound peptidase [14]. Of relevance to the present review, nardilysin regulates β-cell function and identity through the transcriptional factor MafA [15] [15] and also prevents the development of diet-induced steatohepatitis and liver fibrogenesis by regulating chronic liver inflammation [16]. Nardilysin has several other roles unrelated to hepatic or pancreatic function, however, such as modulation of thermoregulation [17]. It also mediates cell migration by acting as a specific receptor for heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth [18]. This protein provides a good example of how paralogs (rather than orthologs) can evolve to develop diverse functions.

2. The Discovery of IDE: An Historical Perspective

More than 70 years ago, Mirsky and Broh–Kahn characterized the existence of a proteolytic activity they named insulinase, which inactivated insulin in rat tissue extracts from liver, kidney and muscle in vitro [19]. The insulinase activity was a mixture of specific and non-specific proteases. Almost four decades of work, within several laboratories, would be conducted on this crude activity before Roth and colleagues eventually cloned the cDNA of Ide, revealing that the insulin-degrading activity within these extracts was attributable primarily if not exclusively to the action of just one protease, IDE [20,21][20][21]. Work on this extract within the early literature, however, resulted in several notable findings. For instance, Mirsky reported that fasting markedly reduced insulinase activity of rat liver extracts as compared with fasted rats subsequently fed a regular diet, suggesting a relationship between the insulin content of pancreas and hepatic insulinase activity [22]. However, refeeding of fasted rats with a high-carbohydrate diet resulted in a greater increase in insulinase than refeeding with a high-fat diet (HFD) [23]. Interestingly, Mirsky and colleagues were the first to report the existence of a substance that, in vitro, inhibited the insulinase activity in liver extracts, and they also demonstrated the effect of crude insulinase-inhibitor preparations on insulin degradation in vivo [24,25,26][24][25][26]. Identification of endogenous proteins that interact with and modulate IDE function has been only partially successful. For example, Brush and colleagues partially purified four competitive IDE inhibitors from human serum, whose molecular weights were in a range that includes insulin (Cohn fraction IV) [27]. Ogawa and colleagues purified an endogenous ~14-kDa protein from rat liver that in a competitive manner inhibited insulin binding and insulin degradation by IDE [28]. Other groups partially purified additional competitive [29] [29] and noncompetitive [30] [30] insulinase inhibitors from rat tissues, but their identities remain unknown. However, Saric and colleagues successfully identified ubiquitin as an IDE-interacting protein that inhibited the proteolytic activity of IDE in a reversible, ATP-independent manner [31]. Although the physiological relevance of the non-covalent, and energy-independent interaction between IDE and ubiquitin remains to be established, these findings may have alternative implications, such as the possibility that IDE interacts with ubiquitin-like modifiers. Finally, Mirsky described that the hypoglycemic effect of oral administration of sulfonylureas in diabetic patients was associated with non-competitive inhibition of insulinase in liver [32], leading to speculation that the mechanism of action of sulfonylureas was inhibition of insulin degradation [33].

The pioneering investigation of the insulinase led to the formulation of an innovative concept to explain the etiology of diabetes. At a time when the classical view of diabetes, proposed by von Mehring and Minkowski as well as Banting and Best [34[34][35],35], was a decrease in the production of insulin by pancreatic β-cells, Mirsky hypothesized that an increase in the rate of insulin degradation by extrapancreatic tissues, could explain the insulin insufficiency in some diabetic patients [36]. The role of IDE on the pathophysiology of diabetes has evolved over time, and it will be discussed in this review.

3. The Function of IDE as a Protease of Insulin

IDE was first characterized by its capacity to degrade insulin into several fragments in vitro, yielding major and minor products. The initial cleavage events occur at the middle of the insulin A and B chains, without specific amino acid requirements, suggesting that substrate recognition by IDE depends on tertiary structure rather than primary amino acid sequence [37,38,39,40][37][38][39][40]. Consistent with this, whereas IDE has a high affinity for insulin (Km ~0.1 µM), proinsulin is a poor substrate that is hydrolyzed at very slow rates, acting as a competitive inhibitor [41,42][41][42]. Likewise, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-II are substrates of IDE, being IGF-II degraded more rapidly than IGF-I, but both acting as competitive inhibitors of IDE [42]. Another potent inhibitor of the insulin-degrading activity of IDE is the leader peptide of rat prethiolase B (P27 peptide), present in peroxisomes [43].

For decades, the standard assay for assessing insulin-protease activity was the use of purified or partially purified enzyme preparations of IDE (e.g., from erythrocytes) and [125I]-labelled insulin. Two methods have been used to quantify the degradation of these radiolabeled peptides, the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation assay and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the former being the most sensitive [44,45][44][45]. Several other IDE activity assays have been developed, such as fluorogenic FRET-based peptide substrates derived from the sequence of bradykinin [46] [46] or other IDE substrates [47]. However, IDE appears to process such short peptides markedly differently from intermediate-sized substrates [48]; for instance, the hydrolysis of such substrates is activated by ATP [49] [49] and other nucleoside polyphosphates [50], certain small molecules [51] [51] and several substrates [52], while these compounds have no effect or actually inhibit the degradation of more physiological substrates. To account for this intriguing substrate specificity of IDE, several substrate-specific degradation assays have been developed for different IDE substrates, including amyloid β-protein (Aβ) [53], glucagon [54] [54] and amylin [55]. Unfortunately, similarly facile assays for insulin degradation have not yet been identified, so insulin degradation is now typically quantified by ELISA or HPLC.

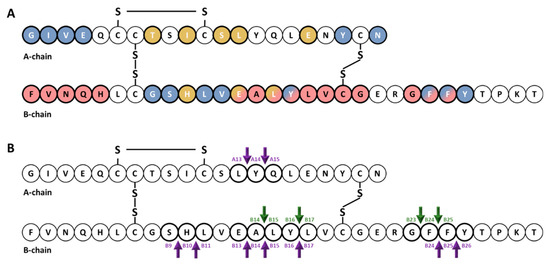

Early studies of the kinetics of insulin degradation suggested that the endosomal apparatus is a physiological site of degradation of internalized insulin in hepatocytes [56,57,58][56][57][58]. Within the acidic endosomal lumen, the insulin-IR complex dissociates and insulin is degraded by endosomal proteases, whereas the IR is recycled to the plasma membrane of the hepatocyte [38]. Over the past several decades, it has been proposed that endosomal degradation of insulin is mediated by the action of three endosomal proteases: Cathepsin D [59], neutral Arg aminopeptidase [60] [60] and IDE [38]. Cathepsin D has been shown to be responsible for the majority of the proteolytic degradation within endosomes, in general [59,61][59][61]. Neutral Arg aminopeptidase is an endosomal Arg convertase involved in the removal of Arg residues from internalized monoarginyl insulin prior endosomal acidification [60]. The action of this protease is highly selective towards [ArgA0]-human insulin peptide, a proinsulin intermediate containing an additional Arg at the amino-terminal insulin A-chain [60]. The role of IDE in endosomal proteolysis of internalized insulin, however, remains controversial, even though many of the primary sites of cleavage of internalized insulin are consistent with those produced by purified IDE [43,61,62][43][61][62]. At an early time, following insulin endocytosis, endosomal proteases account for major degradation products containing an intact A-chain, and cleavages in the B-chain at the PheB24-PheB25, GlyB23-PheB24, TyrB16-LeuB17 and AlaB14-LeuB15 peptide bonds [56][57][58] [56,57,58] (Figure 1). At a later stage, insulin is degraded to its constituent amino acids within endosomes and/or lysosomes [38,58][38][58].

Cartoon illustrating the primary structure and cleavage products of human insulin. (

) primary structure of insulin showing amino acids that interact with IDE (red color) [63][64][65] and with site 1 (blue color) and site 2 (gold color) of the IR [66][67][68][69]. (

) cleavage products generated by endosomal proteases. At an early time, following insulin endocytosis, endosomal proteases account for major degradation products containing an intact A-chain, and cleavages in the B-chain (green arrows). Purple arrows indicate IDE cleavage sites effected by IDE in vitro [39].

The role of IDE as a protease of insulin has been demonstrated over time in cell extracts and intact cells. Overexpression of human IDE (hIde) in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells [70] [70] and monkey kidney COS cells [71] [71] enhanced the extracellular degradation of exogenously applied insulin. Likewise, cell extracts from NIH3T3 cells overexpressing Drosphila IDE (dIde) exhibited enhanced insulin-degrading activity [72]. Based on the use of lysosomotropic agents (which prevent acidification of intracellular lysosomes and endosomes), Kuo and colleagues showed that insulin degradation was affected by intact cells via a dIde-mediated intracellular pathway, independently of the lysosome [71]. In addition, this same team created a stably transfected Ltk− cell line with dexamethasone-inducible overexpression of hIde. IDE expression upon glucocorticoid induction resulted in increased IDE insulin degradation in both cell lysates and intact cells [73].

Consistent with these findings, non-specific inhibitors of IDE decreased intracellular insulin degradation in intact HepG2 cells [74], rat L6 myoblasts [75], and mouse BC3H1 muscle cells [76]. Similarly, monoclonal antibodies against IDE almost completely abolished the insulin-degrading activity of IDE from erythrocytes, and microinjection of these antibodies into HepG2 cells reduced intracellular [125I]-insulin degradation by ~50% [77]. Furthermore, insulin degradation was diminished by ~50% in HepG2 transfected cells with siRNA against hIde, in parallel with a reduction by more than 50% in IDE protein and mRNA levels [78]. Similarly, CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of Ide in CHO cells abolished insulin degradation [79]. Finally, cytosolic and membrane fractions of liver from mice with homozygous deletion of the Ide gene (IDE-KO mouse) showed impaired [125I]-insulin degradation [80]. Taken together, the above-mentioned studies indicated that increasing IDE activity increases cellular insulin degradation, and conversely decreasing its activity reduces insulin degradation.

Despite the large body of evidence supporting a role for IDE in insulin degradation within cultured cells, IDE resides primarily in the cytosol and does not have a signal peptide, so precisely where IDE interacts with insulin or other substrates remains an unresolved question. On the one hand, Zhao and colleagues found that IDE is exported via an unconventional protein secretion pathway [81]. On the other hand, a recent study by Song and colleagues [82] [82] found only very low levels of IDE secretion from HEK293 and BV2 cells, in quantities never exceeding the non-specific release of other cytosolic proteins such as lactate dehydrogenase.

The involvement of IDE in insulin degradation in vivo is similarly controversial. For instance, on the one hand, Farris and colleagues [80], and Abdul–Hay and colleagues [83] [83] found that IDE-KO mice exhibited significant increases in plasma insulin levels. On the other hand, Miller and colleagues [84] [84] and Steneberg and colleagues [85] [85] reported that plasma insulin levels in IDE-KO mice were unchanged relative to wildtype controls. Moreover, we have shown that mice with liver-specific deletion of Ide (L-IDE-KO mice) display normal insulin levels when fed a regular diet [86], but elevated levels when fed a HFD [87], as is discussed in greater detail below.

4. Other Proteolytic Functions of IDE

IDE can degrade several other substrates with lower affinity than insulin, including glucagon [88], somatostatin [89], amylin [90], Aβ [91], amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain [92], amyloid Bri and amyloid Dan [93], atrial natriuretic peptide [94], bradykinin and kallidin [95[95][96],96], calcitonin and β-endorphin [5], growth hormone-release factor [97], transforming growth factor-α [98], oxidized hemoglobin [99], cytochrome c [100], chemokine ligand (CCL)3 and CCL4 [101] [101] and HIV-p6 protein [102].

A role for IDE in the processing of insulin epitopes for helper T cells has been reported by Semple and colleagues [103,104][103][104]. IDE degrades human insulin into peptides that are presented by murine TA3 B-cell antigen-presenting cells to HI/I-Ad-reactive T cells [103]. Of note, IDE is necessary but not sufficient for the recognition of insulin by T cells [103,104][103][104]. More controversial is the role of IDE in the proteasome-independent processing of peptides. As shown by Parmentier and colleagues, MAGE-A3, a cytosolic human tumor protein, is degraded by IDE, leading to different sets of antigenic peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [105]. Immunodepletion of IDE abolished the capacity to produce the antigenic peptide (MAGE-A3168–176), whereas expression of recombinant human IDE was able to produce the antigenic peptide [105]. In addition, Ide RNAi-treated cells reduced the ability of CTLs to recognize tumor cells [105]. On the other hand, Culina and colleagues, using a number of MHC-I class molecules and a loss-of-IDE-function approach in human cell lines and two different mouse strains (IDE-KO mouse and IDE-KO mouse back-crossed to the non-obese diabetic (NOD) strain), concluded that IDE does not play a general major role in peptide loading to MHC-I molecules [106].

Other non-insulin-related proteolytic functions of IDE include degrading cleaved leader peptides of peroxisomal proteins targeted by the type II motif [43] [43] and, possibly, cleaved mitochondrial targeting sequences, in this case by a mitochondrial form of IDE generated by alternative translation initiation [107]. IDE has also been implicated in the formation and/or degradation of “cryptic” peptides (i.e., hidden peptides derived from proteolytic processing of a substrate with different biochemical functions of parent protein), which is the case for IDE-mediated regulation of cryptic peptides from the neuropeptide FF (NPFF) precursor (pro-NPFFA) [108] [108] as well as Aβ [109]. In addition, IDE has been proposed to mediate the degradation of nociceptin/orphanin 1–16 (OFQ/N), a class of neuropeptides involved in pain transmission. Interestingly, the main hydrolytic peptides of OFQ/N produced by IDE, but not the neuropeptide itself, exhibited inhibitory activity towards IDE-mediated degradation of insulin [110].

An example of multiple catalytic and non-catalytic functions of IDE is its role in binding and degrading viral proteins. For instance, Li and colleagues showed that IDE interacts with the glycoprotein E (gE) from varicella zoster virus (VZV) and proposed that IDE is the cellular receptor for the virus [111]. This group subsequently demonstrated that binding of IDE to the N-terminal domain of gE produced a conformational change, increasing its susceptibility to proteolysis [112]. Berarducci and colleagues found that gE/IDE interaction contributed to skin virulence in vivo [113]. In contrast, the gE/IDE interaction was not necessary for VZV infection of T cells in vivo [113]. On the other hand, IDE is necessary and sufficient for degradation of the mature p6 protein of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) [102,114][102][114]. Of note, p6 is degraded 100-fold more efficiently than insulin [102]. Virus replication was reduced by exogenous insulin or pharmacological inactivation of IDE with the inhibitor 6bK [102,115][102][115].

5. Non-Proteolytic Functions of IDE

IDE has been reported to directly interact with androgen and glucocorticoid receptors, enhancing specific DNA binding of both receptors [116]. Non-competitive inhibition of IDE’s catalytic activity did not block the binding of the androgen receptor to IDE, but competitive inhibition of IDE blocked its binding, suggesting that IDE-binding sites for the receptor and insulin are identical or overlapping [116]. Interestingly, dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid, significantly reduced insulin binding to IDE without affecting expression levels of the protease in rat hepatoma cells, most likely by inducing a conformational change or blocking insulin-binding sites [117]. Conversely, the steroid’s effect was blocked by insulin [117]. The interaction of IDE with androgen and glucocorticoid receptors may be of relevance for steroid hormone action and metabolism, the crosstalk between insulin and steroid hormones, and the pathophysiology of glucocorticoid-mediated insulin resistance [118].

Intriguingly, IDE co-localizes with the ~50-amino acid cytoplasmic tail of the scavenger receptor type A (SR-A), an important domain for SR-A function, in mouse macrophages [119]. The biological significance of this interaction is uncertain, because IDE deficiency in bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) did not alter protein levels of SR-A or its ability to uptake low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, albeit its deficiency in these cells was associated with higher levels of intermediate density lipoproteins, LDL-cholesterol and accelerated atherogenesis in LDL receptor knockout (Ldlr−/−) mice [119]. Considering that SR-A participates in multiple cellular processes, including regulation of inflammatory cytokine synthesis through its interaction with TLR4, it is tempting to hypothesize that IDE deficiency in macrophages may cause an inflammatory milieu surrounding the arterial wall, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of atherogenesis.

IDE co-immunoprecipitates with SIRT4, a protein with no histone deacetylase activity but with associated ADP-ribosyl-transferase activity that resides in the mitochondrial matrix [120]. SIRT4 expression is detected in several mouse tissues including liver [121[121][122],122], and human pancreatic β-cells [120,122][120][122]. SIRT4 depletion in INS1 and MIN6 cells markedly increased insulin secretion without altering basal secretion and intracellular insulin content [120,122][120][122]. Conversely, SIRT4 overexpression in INS1 cells suppressed glucose-induced insulin secretion. Of note, insulin secretion stimulated with the secretagogue KCl, which bypasses mitochondrial activation, remained unaltered in SIRT4-depleted INS-1E cells [120]. Once more, the biological significance of this interaction remains undeciphered, because there are no reports on the ADP-ribosylation of IDE, and the mitochondrial function of IDE is not clarified. However, IDE depletion in INS1-E cells using siRNA-IDE and shRNA-IDE significantly decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [123]. The contributions of the cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of IDE in regulating insulin secretion, and the association of the later with SIRT4, warrants further research.

IDE has been identified as an interacting partner of intermediate filaments, one of the three major cytoskeletal components that serve as a scaffold for signaling molecules, modulating their distribution and activity [124]. Specifically, IDE has been shown to interact with disassembled and soluble vimentin/nestin complexes during mitosis [125]. Vimentin plays a dominant role in targeting IDE to the complex and binds to IDE with higher affinity than nestin. Phosphorylation of vimentin is not required for its binding to IDE, but the interaction is enhanced by vimentin phosphorylation at Ser-55. On the other hand, binding of IDE to nestin promotes the disassembly of vimentin intermediate filaments, most likely by rendering the phosphorylated vimentin more accessible for IDE. The binding of IDE to nestin is phosphorylation independent. Interestingly, the binding of nestin or phosphorylated vimentin suppressed by ~2-fold the insulin-degrading activity of IDE but increased its proteolytic activity toward bradykinin [125]. These data suggest that IDE may be involved in regulating the turnover and/or subcellular localization of cytosolic proteins and peptides. In this context, it has to be noted that integrins are a major family of cell adhesion receptors that mediate attachment of cells to the extracellular matrix. Recruitment of integrins and other proteins forms multi-protein complexes on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane named focal adhesions, which allow the anchoring of the actin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane, providing a linkage between the extracellular environment and the cytoplasm. Integrins do not have intrinsic kinase activity and signaling depends upon the recruitment and activation of focal adhesion kinase (FaK), a cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinase [126,127][126][127]. Significantly, Liu and colleagues identified IDE as a binding partner that interacts with C-terminal domain of FaK [128] [128]. The relevance of the interaction between IDE and FaK in regulating recruitment of cytoskeletal proteins and the assembly of focal adhesions, a process that is important for cell migration, survival and proliferation, remains to be elucidated.

IDE, in a non-proteolytic manner, binds to α-synuclein oligomers leading to the formation of stable and irreversible complexes, precluding amyloid formation [129,130][129][130]. α-synuclein is a synaptic signaling protein with three domains—the N-terminus, which interacts with membranes, the amyloidogenic domain and the C-terminus, which is involved in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease [131]. Interestingly, the catalytic activity of IDE on a bradykinin-based fluorogenic substrate was increased in the presence of α-synuclein [129]. The interaction between both proteins appears to require electrostatic attraction involving the exosite region of IDE, which is positively charged, and the C-terminus of α-synuclein, which contains many negatively charged amino acids [130]. The role of IDE in the turnover of amyloidogenic proteins and the non-proteolytic prevention of toxic amyloid formation—in the case of α-synuclein via a so-called “dead-end chaperone function”—appears to be important for pancreatic β-cells function. In this connection, Steneberg and colleagues showed that genetic deletion of Ide in pancreatic β-cells led to the formation α-synuclein oligomers and fibril accumulation, which was associated with impaired insulin secretion and reduced granule turnover, possibly by disruption of the microtubule network [85].

Sorting nexin 5 (SNX5) is a member of the sorting nexin family that regulates intracellular trafficking and is abundantly expressed in kidney [132,133][132][133]. Its expression is reduced in Zucker rats, a model of obesity, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance [134]. The Snx5 gene is located on chromosome 20p, a susceptibility quantitative trait locus for high fasting plasma insulin levels and insulin resistance [135]. Li and colleagues have shown that IDE colocalizes with SNX5 in the brush border membrane of proximal tubules and the luminal side of distal convoluted tubules of human and rat kidneys, in addition to the plasma membrane and perinuclear area of human renal proximal tubule cells (hRPTCs) [134]. Furthermore, exposure of hRPTCs to insulin increased colocalization and co-immunoprecipitation of IDE and SNX5. Interestingly, SNX5-depleted hRPTCs exhibit reduced IDE activity and protein levels, in parallel with decreased expression of the IR and downstream insulin signaling [134,136][134][136]. Similarly, renal subcapsular infusion of SNX5-specific siRNA decreased IDE mRNA and protein expression in kidneys of mice [134]. These studies underline the potential significance of renal IDE in the regulation of circulating insulin levels as well as insulin sensitivity in kidneys.

The human retinoblastoma (RB) protein acts as a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates cell cycle progression at the G1/S transition through its interaction with the E2F family of transcription factors [137]. IDE co-purifies with RB on proteasomal preparations of breast cancer and hepatoma cells [138]. Similarly, IDE co-immunoprecipitates with the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) [139]. IDE accelerates PTEN degradation by SIRT4 in response to nutritional starvation stresses [139]. Although the underlying molecular mechanisms have not been fully elucidated, these findings support a role for IDE in insulin-driven oncogenesis. Likewise, Tundo and colleagues have hypothesized that IDE, in a heat shock protein-like fashion, may be implicated in cell growth regulation and cancer progression [140]. In normal cells (human fibroblasts cell line and human peripheral blood lymphocytes) and malignant cells (human neuroblastoma cell line (SHSY5Y) and human lymphoblastic-like cells line (Jurkat cells)) exposed to heat shock, H2O2 and serum starvation, IDE is markedly up-regulated at both protein and mRNA levels. Additionally, delivery of IDE siRNA to SHSY5Y cells led to extensive apoptotic cell death; and administration of ATRA (a vitamin A precursor used in the clinical treatment of neuroblastoma) significantly decreased intracellular IDE content [140].

6. Molecular and Biochemical Characteristics of IDE

IDE is synthesized as a single polypeptide with a molecular weight of ~110 kDa by a gene located on human chromosome 10 q23–q25, and mouse chromosome 19, respectively [20,70][20][70]. Ide coding mutations have been associated with the development of T2DM in the Goto–Kakizaki rat model [141]. Fakhrai–Rad and colleagues identified two missense mutations (H18R and A890V) in IDE that decrease the ability to degrade insulin by 31% in transfected cells. They reported a synergistic effect of the two mutations on insulin degradation, which is somewhat puzzling given that H18R is present within the mitochondrial targeting sequence of IDE produced by alternative translation initiation [107]. Farris and colleagues, by contrast, found that recombinant IDE containing the A980V mutation alone exhibited reduced catalytic efficiency of both insulin and Aβ degradation, suggesting that this mutation is most relevant to proteolytic function [142]. Interestingly, no effect on insulin degradation was seen in cell lysates of Ide-transfected COS cells, suggesting that the effect may be dependent upon receptor-mediated internalization of the hormone [141,142][141][142].

IDE assembles as a stable homodimer, although it can exist as an equilibrium of monomers, dimers and tetramers [52]. Each monomer is comprised four homologous domains (named 1–4). The first two domains constitute the N-terminal portion (IDE-N), and the last two the C-terminal portion (IDE-C). IDE-N and IDE-C are joined by an extended loop of 28 amino acids. In the human IDE dimer, the interface between the two monomers is formed by 18 residues of domains 3 and 4 (IDE-C) [143]. Interestingly, the crystal structure of rat IDE, obtained by Hersh and colleagues [144], revealed a different homodimer interface than human IDE. In rat IDE, deletion of the last 18 amino acids abolished homodimer formation while simultaneously eliminating allosteric effects reflective of inter-subunit cooperativity [144]. The active site of IDE consists of a catalytic tetramer, HxxEHx76E, located inside domain 1, in which two histidine residues (H108 and H112) and a glutamate (E189) coordinate the binding of the Zn2+ ion and a second glutamate (E111) plays an essential role in catalysis. Glutamate E111 activates a catalytic water molecule for the nucleophilic attack that mediates peptide hydrolysis [63,145][63][145]. Although the catalytic site is entirely inside IDE-N domain, the IDE-C is necessary for correct substrate recognition [146]. Site-directed mutagenesis revealed that mutating IDE H108 (i.e., H108L and H108Q) abolished catalytic activity of the enzyme, but not the ability to bind insulin. Similarly, mutation E111Q abolished proteolytic activity [145,147][145][147].

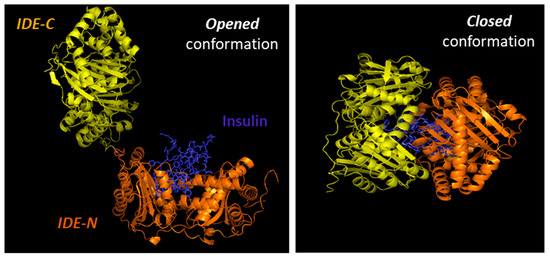

Substrates for IDE are almost exclusively intermediate-size (~20–40 amino acids) peptide substrates, with rare exceptions, such as oxidized hemoglobin [99]. This size preference is the result of the overall structure of IDE, which resembles a clamshell, with two bowl-shaped domains (IDE-C and IDE-N) facing one another, connected by a hinge, and together forming a ~13,000-Å3 internal chamber (Figure 2). These domains can pivot on the hinge, thus adopting “open” and “closed” conformations. Transition to the open conformation is required for entry of substrates and exit of proteolytic products, and there is strong evidence that transition to the closed conformation is a requirement for proteolytic processing. Consistent with this, site-directed mutagenesis revealed that the complete active site of IDE is in fact bipartite, consisting of residues within both IDE-N and IDE-C [148], a conclusion that is confirmed by numerous crystal structures [149]. Due to the placement of the bipartite active site within the chamber of the closed protease, substrates must be small enough to fit completely within this chamber to be processed. To facilitate binding and subsequent cleavages at the catalytic site, larger substrates interact with an exosite within domain 2 located ~30 Å away from the active-site Zn2+, which anchors the N-terminus of several substrates [50]. Because of the unusual requirement that substrates fit within the internal chamber, the substrate selectivity of IDE is based more on the tertiary structure of substrates than their primary amino acid sequence. IDE shows some preference for cleavage at basic or bulky hydrophobic residues at the P1’site of the target protein [62], but this subsite specificity is not strict, and IDE commonly cleaves at vicinal peptide bonds within substrates [53] [53]. Of note, substrates containing positively charged residues at their C-terminus are poor IDE substrates [63]. Thus glucagon, which lack of positively charged amino acids at the C-terminal is an IDE substrate, but not glucagon-like peptide [63].

Cartoon illustrating the binding of insulin by IDE. IDE is in an equilibrium between “opened” and “closed” conformational states. In the absence of a substrate (e.g., insulin), IDE is preferentially in the closed conformation. IDE must adopt the open conformation for substrates to enter the internal chamber, whereas the protease must assume the closed conformation for proteolysis to occur. Release of the cleavage products requires a return to the open conformation.

The requirement for a transition between the “closed” and “open” conformations has an additional implication for the activity of IDE. There is extensive hydrogen bonding between the two halves of IDE, creating a “latch” that tends to maintain the protease in the closed conformation [63,150,151][63][150][151]. Consistent with this idea, most crystal structures of IDE, whether empty or occupied by substrate, show the protease in the closed conformation [63]. Notably, mutation of some of the residues mediating this interaction has been shown to activate the protease by as much as 15-fold [63]. It is estimated that in the absence of other factors, ~99% of IDE molecules are normally in the closed conformation (M.L. unpublished observations), suggesting that a significant of latent IDE activity could be untapped, for example, by compounds that disrupt this “latch” [51].

Interestingly, somatostatin, a hormone produced and secreted by the hypothalamus and in the pancreas by δ-cells, that inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [152], in addition to being a substrate of IDE, also regulates its function. Somatostatin binds to two additional exosites named “somatostatin-binding exosites” which play different roles according to the size of the substrates and its binding mode to the IDE catalytic cleft [95].

As mentioned above, a mitochondrial isoform of IDE was identified by Leissring and colleagues, which is formed by alternative translation initiation [107]. The open reading frames of human, rat, and mouse Ide cDNAs contain two in-frame translational codons encoding proteins beginning either at the first (Met1-IDE) or the 42nd amino acid (Met42-IDE). Met42-IDE (the shorter isoform) is the predominant isoform expressed in tissues and culture cells [107], because the nucleotide sequence surrounding the second initiation codon contains a better Kozak consensus sequence for initiation of translation. Although the Met1-IDE isoform is predicted to be less efficiently translated, it could nevertheless account for a significant fraction of total cellular IDE [107]. Currently, it is uncertain whether the mitochondrial isoform plays a major role in human disease.

In addition to the two possible translation initiation sites (Met1-IDE and Met42-IDE), Farris and colleagues identified a novel splice isoform in which exon 15a is replaced by a novel exon, 15b [153]. The resultant variant is widely expressed and present in both cytosol and mitochondria. The 15b-IDE isoform can exist as homodimer or as heterodimer with the 15a isoform. The catalytic efficiency of the 15b-IDE isoform is significantly lower than the 15a-IDE isoform [153].

IDE expression is regulated during cell differentiation and growth. During rat development (6–7 days of age) to adulthood, Ide mRNA levels increased in brain, testis and tongue with a concomitant decreased expression in muscle and skin but remained unchanged in other tissues. In the adult rat, Ide mRNA is higher in testis, tongue and brain, and lower in spleen, lung, thymus and uterus [2,154][2][154]. Interestingly, IDE activity is affected by aging. The highest IDE activity is observed in muscle, liver and kidneys of 4-week-old rats. The IDE activity in muscle and liver at 7 weeks of age is lower than at 4 weeks, with similar activity in kidney. The lowest activity of IDE was observed in muscle, liver and kidneys of 1-year-old rats [155].

7. Subcellular Localization of IDE

The subcellular localization of IDE is mainly cytosolic [37,156[37][156][157][158],157,158], but it has been reported to be present in several other subcellular compartments, including endosomes [58[58][159][160],159,160], peroxisomes [43], mitochondria [107], plasma membrane [161,162[161][162][163][164][165],163,164,165], endoplasmic reticulum [166], exosomes [167], the extracellular space [166] [166] and even in human cerebrospinal fluid [168]. If IDE is primarily cytosolic, its role as an insulin protease seems to be called into question. Two main pathways for insulin internalization have been described. At physiological concentrations, insulin is internalized through an IR-mediated process (see reference [1] [1] for a comprehensive review of IDE’s role on insulin uptake and clearance), whereas at higher concentrations a non-receptor mediated uptake internalizes insulin to endosomes [169]. In both pathways, insulin is internalized in endosomes, which begs an important question: How can insulin gain access to the cytosol to be degraded by IDE? Several studies proposed that internalized insulin is probably released to the cytosol by endosomes [170]. The mechanism by which insulin is transported through the membrane of endosomes and enter the cytosol is not well understood, but it has been proposed a two-step process involving acidification of the endosome and unfolding of insulin molecules, which help it pass through the membrane [170]. Modulation of IDE activity may have a significant impact in the accumulation of cytosolic and nuclear insulin or insulin-bound cytoplasmatic proteins [171,172,173,174][171][172][173][174].

An alternative locus for the interaction between IDE and insulin (and other substrates) is the extracellular space. As mentioned, IDE does not have a signal peptide and is not exported via the classical secretion pathway [81]. Many reports indicate that IDE is secreted in significant quantities from various cell types (e.g., [161,166][161][166]), but a recent analysis [82] suggests that IDE release from cultured cells might be non-specific. There is a great need for additional research on this topic, as it is of central significance to the functional role of IDE in regulating the levels of insulin and other IDE substrates.

8. Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation of IDE

Although the role of IDE in the regulation of hepatic insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis has been investigated [86[86][87],87], the physiological regulation of its expression and activity in hepatocytes remains poorly understood. In human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells grown in normal glucose medium, exposure to insulin for 24-h did not regulate Ide mRNA or protein levels [175]. Likewise, in the presence of high glucose levels, insulin increased expression of Ide mRNA, but without changes in levels of IDE [175]. However, insulin increased hepatic IDE activity, but this insulin-mediated effect was abolished in the presence of high glucose levels [175]. The underlying mechanism(s) by which 24-h exposure to insulin regulates IDE activity remains to be deciphered. As mentioned above, human Ide mRNA undergoes alternative splicing in exon 15 [153]. Pivovarova and colleagues showed that the relative proportion of the more proteolytically active 15a splice isoform was increased after insulin treatment, independently of glucose levels [175].

Insulin-mediated regulation of IDE has also been investigated in mouse primary hippocampal neurons. Contrary to hepatocytes, exogenous insulin application upregulates IDE protein levels, and this insulin-mediated effect was abolished by inhibition of the insulin-signaling component phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [176]. These findings suggest that, within certain cell types, there is a negative feedback mechanism whereby insulin-mediated activation of IR upregulates IDE to prevent chronic activation of the pathway in the presence of high insulin levels.

The effects of glucagon on IDE function in hepatocytes was investigated by Wei and colleagues. In a time-dependent manner, glucagon (100 ng/mL) upregulated IDE protein levels in Hepa 1c1c7 cells. A similar pattern was observed after preincubation of hepatic cells with forskolin (10 µM), an activator of protein kinase A (PKA), suggesting that the glucagon-mediated regulation of IDE proceeds via a cAMP/PKA-dependent pathway [177]. The physiological and pathophysiological relevance of these findings awaits further validation in vivo.

Lin and colleagues demonstrated that Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), a classical adaptor in the Fas-FasL signaling pathway, which is phosphorylated in response to members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, regulates the expression of IDE at the transcriptional level, without affecting the stability of Ide mRNA in HepG2 cells [178]. FADD knockdown in HepG2 cells by siRNA resulted in downregulation of both mRNA and protein levels of IDE without change in IDE mRNA stability. Similar effects on IDE mRNA and protein levels were observed in the liver of mice overexpressing FADD-D (a mimic of constitutively phosphorylated FADD) as well as in primary hepatocytes cultured from these mice, effects that were attributable to reduced stability of IDE protein [178]. Interestingly, in primary hepatocytes from FADD-D mice, nuclear translocation of the transcription factor forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) is enhanced, and the transcriptional activity of the IDE promoter in response to FADD knockdown in HEK293T cells was decreased. Furthermore, the transcriptional activity of the Ide promoter was reduced by expressing FoxO1 in HEK293T cells [178]. Altogether, these results point out that FADD phosphorylation may reduce the expression of IDE by promoting the nuclear translocation of FoxO1. The detailed regulatory mechanism by which FADD phosphorylation regulates transcriptional activity of the Ide promoter in hepatocytes requires further experimental confirmation. In addition, these findings open an avenue to explore whether the insulin signaling pathway through FoxO1 regulates IDE levels in hepatocytes.

The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) is a seven-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor present in liver, and its activation by endocannabinoids stimulates lipogenic genes in hepatocytes, leading to increased fatty acid synthesis [179]. Pancellular genetic deletion of CB1 in mice resulted in resistance to diet-induced obesity, and liver-specific deletion in mice fed a HFD showed lower insulin resistance, hyperglycemia and steatosis [179]. In HepG2 cells, the endocannabinoid anandamide, a metabolite of the non-oxidative metabolism of arachidonic acid that is a partial agonist of CB1, causes down-regulation of IDE in a time-dependent manner, in parallel with Ser307 phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) [180]. Likewise, acute treatment with anandamide or feeding with a HFD reduced hepatic IDE levels, in parallel with insulin resistance in mice. The CB1-mediated regulation of IDE was further corroborated by the finding that hepatic IDE expression is downregulated in mice that overexpress CB1 in hepatocytes (htgCB1 mice) but not in CB1 knockout mice [180] [180]. Of note, htgCB1 mice displayed down-regulation of IDE and its proteolytic activity, but unaltered levels of phosphorylated carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), in parallel with hepatic insulin resistance, lower insulin clearance and moderate hyperinsulinemia [180].

The impact of inflammation mediators on IDE function has also been examined in hepatocytes and pancreatic cells. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates inflammation associated with insulin resistance in the liver and other tissues [181]. In HepG2 cells, exposure to IL-6 increases IDE protein levels [182]. Conversely, in livers of IL-6 knockout mice, which develop glucose intolerance without a change in insulin sensitivity, hepatic insulin clearance is reduced, which is associated with reductions in the levels of IDE mRNA, protein and activity [182]. In addition, IL-6 knockout mice exhibited diminished C-peptide secretion after administration of an intraperitoneal (IP) glucose bolus, and reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in isolated pancreatic islets, leading to lower fasting plasma insulin levels [182]. In the opposite direction of IL-6’s effect on hepatic IDE function, exposure to tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) decreased IDE mRNA and protein levels in Hepa 1c1c7 cells [177]. Thus, additional work is warranted, but these findings suggest IDE may play a role in the mechanisms linking inflammation to the regulation of pancreatic insulin secretion and hepatic insulin resistance.

In addition to the aforementioned, other modulators can regulate IDE protein and activity levels. Thus, ATP and other nucleoside polyphosphates, as well as polyphosphate alone, induce dose-dependent allosteric inhibition of insulin degradation and, concomitantly, activation of short fluorogenic peptide substrates at physiologically relevant concentrations (1–5 mM) [50,183][50][183]. Interestingly, the activating effect is stronger for nucleoside triphosphates than nucleoside di- or monophosphates, and is attenuated in the presence of Mg2+ [50,184][50][184]. Polyphosphate binding has been shown to occur at a specific region within IDE, known as the polyanion-binding domain [144], and appears to mediate activation of the protease towards short substrates by facilitating the transition from the closed state to the open conformation [49,50][49][50]. Camberos and colleagues reported that IDE has ATPase activity [185], but this was not confirmed by other investigators (M. Leissring, unpublished observations) and a molecular mechanism for this functionality is not evident from the crystal structures of IDE [63].

Acidic pH also affects the ability of IDE to bind insulin and alter its degradation by inducing dissociation of the oligomerization state into monomeric units. Since IDE is most active at neutral and basic pH, suggest that cellular acidosis may regulate insulin signaling and degradation [186]. Further studies are necessary to understand the impact of clinically relevant diabetic ketoacidosis, and starvation ketoacidosis stimulated by the combination of low insulin and high glucagon on IDE function.

Nitric oxide (NO) production is known to play an important role in permissive regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and hepatic insulin resistance [187,188,189][187][188][189]. In this connection, it is interesting to note that S-nitrosylation of IDE, mediated by S-nitrosoglutathione, a potent physiologically relevant NO donor source in cells, inhibited the proteolytic activity of IDE [96] [96]. Notably, NO donors exert this effect in a non-competitive manner, without affecting insulin binding to IDE or the insulin degradation products it produces [190]. Similarly, Cordes and colleagues showed that NO inhibited the degrading activity of IDE in rat liver homogenates in a dose-dependent manner [191]. Somewhat controversially, Natali and colleagues have postulated that the increased insulin clearance evoked by systemic blockage of endogenous NO synthesis in humans may be accounted for by effects on IDE function in liver [192]; however, the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of this proposed mechanism of IDE regulation on hepatic insulin action and signaling awaits further confirmation.

IDE is vulnerable to oxidative damage in multiple ways. For instance, IDE has been shown to be covalently modified and consequently inactivated by 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), an oxidative byproduct of lipid metabolism [193,194][193][194]. Of note, in the brains of mice, HNE-modified IDE accrues in an age-dependent manner, being particularly abundant in brain regions affecting in Alzheimer’s disease [193]. HNE, H2O2 and other oxidizing agents act, not only, to inhibit IDE proteolytic activity, but also promote the proteolysis of IDE itself by other proteases [194]. Conversely, dietary vitamin E supplementation, a classical lipophilic antioxidant that protect against free radicals [195], increased IDE mRNA levels in livers of rats, which was associated with improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity [196].

The effects of caloric restriction and exercise on IDE function have been examined in mice, as well. Mice fed a low-protein diet for 14 weeks showed improved glucose tolerance and hepatic insulin sensitivity, in parallel with reduced insulin secretion and clearance, which was associated with ~50% reduction in IDE protein levels in the liver [197]. Likewise, caloric restriction (food restriction of 40%) for 21 days resulted in improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in rats, which was associated with lower hepatic IDE protein levels [196]. Mice subjected to a single bout of exercise on treadmill for 3-h showed reduced glycemia and insulin sensitivity, in parallel with higher insulin secretion in isolated islets and insulin clearance, which was associated with increased expression of IDE in the liver [198].

Exposure to increasing amounts of free fatty acids (FFA) released from adipose tissue promotes the development of hepatic insulin resistance and impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells [199[199][200],200], and some reports suggest that IDE may be either affected by or involved in this phenomenon. Early reports showed that FFA reduced leakage of IDE from isolated rat hepatocytes and inhibited the proteolytic activity of IDE released from adipocytes [201,202][201][202]. Svedberg and colleagues investigated the effect of different fatty acids on insulin binding, degradation and action in isolated rat hepatocytes, finding that different fatty acids rapidly decreased insulin binding and degradation in isolated hepatocytes [203]. Furthermore, the effect of FFA was specifically on the rate of insulin receptor internalization and/or recycling [203]. Of note, Hamel and colleagues identified a fatty acid-binding motif within IDE and subsequently examined the effect of FFA and their acyl-coenzyme A thioesters on IDE partially purified from rat livers [204]. They observed that both saturated and unsaturated long-chain FFA, and the corresponding acyl-coenzyme A thioesters, inhibited insulin degradation in a non-competitive manner, but did not inhibit binding of the hormone to IDE [204]. In addition to the effect of FFA on IDE activity, Wei and colleagues investigated the impact of FFA on IDE expression, showing that palmitic acid (300 µM) augmented IDE protein levels in Hepa 1c1c7 cells [177]. These results are not in accordance with effects of FFA on IDE expression in brain, where palmitic acid reduced, while docosahexaenoic increased, IDE protein levels in neuron [205]. Furthermore, palmitic acid attenuated the effect of docosahexaenoic acid in brain [205]. In light of these studies, it is tempting to hypothesize that obese patients are exposed to increasing amounts of saturated FFA (e.g., palmitic acid) released from mesenteric and omental fat via the portal system, which would be predicted to inhibit both proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions of IDE, in turn decreasing insulin clearance, whether directly by reducing IDE levels and/or activity or indirectly via mechanisms involving IR internalization and/or recycling. This mechanism may help explain the insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia seen in obese patients, but further research is needed to validate this hypothesis.

9. Pharmacological Modulation of IDE

The proteolytic activity of IDE in vitro is sensitive to non-specific inhibitors such as EDTA (a metal-chelating agent), 1,10-phenanthroline (a Zn2+ chelator), p-hydroxymercuribenzoate and iodoacetate (cysteine proteinase inhibitors), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and p-chloromercuribenzoate (sulfhydryl-reactive compounds) and bacitracin (cyclic polypeptides from B. subtilis that inhibit bacterial growth) [206,207,208][206][207][208]. Importantly, IDE is sensitive to inhibition by sulfhydryl-directed reactions, such as alkylation (NEM) and oxidative inactivation (H2O2) [145,148,194,209,210][145][148][194][209][210]. The multi-functional roles of IDE, and the fact that most existing inhibitors were non-selective, inspired the development of pharmacological inhibitors of IDE. The first potent and selective IDE inhibitor was developed by Leissring and colleagues, who used a rational drug design approach based on analysis of the subsite sequence selectivity of IDE, resulting in Ii1, a highly potent (Ki = 2 nM) peptide hydroxamic acid [211]. Another thiol-targeting IDE inhibitor developed by this group, ML345, is of interest because it selectively targets extracellular IDE while sparing cytosolic IDE via the formation of a redox-sensitive disulfide bond [209]. More recently, a potent and commercially available IDE inhibitor, 6bK, was developed by Maianti and colleagues [115], which is highly selective because it targets the exosite rather than the active site within IDE. Further, 6bK is notable because it exhibited multiple antidiabetic properties in vivo [115]. A recent drug-repurposing screen conducted by Leroux and colleagues [212] [212] identified an existing drug, ebselen (EB), a synthetic organoselenium compound with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, as a potent pharmacological inhibitor of IDE (apparent IC50 against insulin degradation = 14 nM) [212,213,214,215][212][213][214][215]. EB was found to inhibit IDE via unusual mechanisms of action. First, EB was shown to be a reversible inhibitor [212], despite the fact that it is known to covalently modify cysteine residues [216], and despite the fact that it was inactive against a cysteine-free form of IDE [212]. While the reversibility of EB action would suggest the compound does not directly modify thiols, an independent study found that a biotinylated form of EB interacts with IDE in a covalent manner [217]. Second, EB was found to shift the quaternary structure of IDE, destabilizing the homodimer and promoting monomer formation [212]. Interestingly, EB has an insulin-mimetic action, reducing hyperglycemia, enhancing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [218], restoring glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells [219], and improving hepatic insulin signaling and β-cell survival [220], suggesting that EB-mediated IDE inhibition may be involved in the mechanism of action of this compound. Consistent with the idea that IDE inhibition could potentiate insulin signaling, Leissring and colleagues identified peptidic IDE inhibitors via phage display that promote insulin-dependent collagen production in skin fibroblasts and migration in cultured keratinocytes, suggesting these compounds may have therapeutic value for promoting wound healing [221]. Finally, in another interesting application of IDE inhibitors, Demidowich and colleagues proposed the utility of using bacitracin in blood samples to counteract insulin degradation from IDE released during hemolysis, which complicates interpretation of clinical data [222].

Indirect effects of several diabetes drugs, such as thiazolidinediones, on the levels and functionality of IDE have also been investigated. Pioglitazone, an insulin sensitizer that enhances insulin action and decreases hepatic gluconeogenesis in liver [223] [223], increased IDE mRNA and protein levels in a time-dependent manner in the mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa 1c1c7 [177]. In addition, pioglitazone administration resulted in higher IDE mRNA and protein levels in livers of mice fed a HFD concomitant with improved insulin sensitivity and lower circulating glucose and insulin levels [177]. Troglitazone was the first thiazolidinedione to be used in diabetic patients but was subsequently withdrawn for clinical use due to its hepatotoxicity [224]. Troglitazone administration reduced hepatic triglyceride content and decreased de novo lipogenesis, in parallel with higher insulin clearance in rats fed a high-sucrose diet for two weeks. These metabolic improvements were associated with augmented IDE activity, but similar IDE protein levels in the liver [225].

References

- Najjar, S.M.; Perdomo, G. Hepatic insulin clearance: Mechanism and physiology. Physiology 2019, 34, 198–215.

- Kuo, W.L.; Montag, A.G.; Rosner, M.R. Insulin-degrading enzyme is differentially expressed and developmentally regulated in various rat tissues. Endocrinology 1993, 132, 604–611.

- Hooper, N.M. Families of zinc metalloproteases. FEBS Lett. 1994, 354, 1–6, doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01079-x.

- Rawlings, N.D.; Morton, F.R.; Kok, C.Y.; Kong, J.; Barrett, A.J. MEROPS: The peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D320–D325, doi:10.1093/nar/gkm954.

- Fernandez-Gamba, A.; Leal, M.C.; Morelli, L.; Castaño, E.M. Insulin-degrading enzyme: Structure-function relationship and its possible roles in health and disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 3644–3655.

- Rawlings, N.D.; Barrett, A.J. Homologues of insulinase, a new superfamily of metalloendopeptidases. Biochem. J. 1991, 275 Pt 2, 389–391, doi:10.1042/bj2750389.

- Kole, H.K.; Muthukumar, G.; Lenard, J. Purification and properties of a membrane-bound insulin binding protein, a putative receptor, from Neurospora crassa. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 682–688, doi:10.1021/bi00217a014.

- Kole, H.K.; Smith, D.R.; Lenard, J. Characterization and partial purification of an insulinase from Neurospora crassa. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 297, 199–204, doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90662-g.

- Fricke, B.; Betz, R.; Friebe, S. A periplasmic insulin-cleaving proteinase (ICP) from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus sharing prop-erties with protease III from Escherichia coli and IDE from eucaryotes. J. Basic Microbiol. 1995, 35, 21–31, doi:10.1002/jobm.3620350107.

- Cheng, Y.S.; Zipser, D. Purification and characterization of protease III from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 4698–4706.

- Dykstra, C.C.; Kushner, S.R. Physical characterization of the cloned protease III gene from Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 163, 1055–1059, doi:10.1128/JB.163.3.1055-1059.1985.

- Kim, S.; Lapham, A.N.; Freedman, C.G.; Reed, T.L.; Schmidt, W.K. Yeast as a tractable genetic system for functional studies of the insulin-degrading enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 27481–27490, doi:10.1074/jbc.M414192200.

- Adames, N.; Blundell, K.; Ashby, M.N.; Boone, C. Role of yeast insulin-degrading enzyme homologs in propheromone pro-cessing and bud site selection. Science 1995, 270, 464–467, doi:10.1126/science.270.5235.464.

- Cohen, P.; Pierotti, A.R.; Chesneau, V.; Foulon, T.; Prat, A. N-arginine dibasic convertase. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 248, 703–716, doi:10.1016/0076-6879(95)48047-1.

- Nishi, K.; Sato, Y.; Ohno, M.; Hiraoka, Y.; Saijo, S.; Sakamoto, J.; Chen, P.M.; Morita, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Iwasaki, K.; et al. Nar-dilysin Is Required for Maintaining Pancreatic β-Cell Function. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3015–3027, doi:10.2337/db16-0178.

- Ishizu-Higashi, S.; Seno, H.; Nishi, E.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ikuta, K.; Tsuda, M.; Kimura, Y.; Takada, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; et al. Deletion of nardilysin prevents the development of steatohepatitis and liver fibrotic changes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98017, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098017.

- Hiraoka, Y.; Matsuoka, T.; Ohno, M.; Nakamura, K.; Saijo, S.; Matsumura, S.; Nishi, K.; Sakamoto, J.; Chen, P.M.; Inoue, K.; et al. Critical roles of nardilysin in the maintenance of body temperature homoeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3224, doi:10.1038/ncomms4224.

- Nishi, E.; Prat, A.; Hospital, V.; Elenius, K.; Klagsbrun, M. N-arginine dibasic convertase is a specific receptor for hepa-rin-binding EGF-like growth factor that mediates cell migration. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 3342–3350, doi:10.1093/emboj/20.13.3342.

- Mirsky, I.A.; Broh-Kahn, R.H. The inactivation of insulin by tissue extracts; the distribution and properties of insulin inacti-vating extracts. Arch. Biochem. 1949, 20, 1–9.

- Affholter, J.A.; Fried, V.A.; Roth, R.A. Human insulin-degrading enzyme shares structural and functional homologies with E. coli protease III. Science 1988, 242, 1415–1418, doi:10.1126/science.3059494.

- Duckworth, W.C.; Hamel, F.G.; Bennett, R.; Ryan, M.P.; Roth, R.A. Human red blood cell insulin-degrading enzyme and rat skeletal muscle insulin protease share antigenic sites and generate identical products from insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 2984–2987.

- Broh-Kahn, R.H.; Mirsky, I.A. The inactivation of insulin by tissue extracts; the effect of fasting on the insulinase content of rat liver. Arch. Biochem. 1949, 20, 10–14.

- Broh-Kahn, R.H.; Simkin, B.; Mirsky, A. The inactivation of insulin by tissue extracts. V. The effect of the composition of the diet on the restoration of the liver insulinase activity of the fasted rat. Arch. Biochem. 1950, 27, 174–184.

- Mirsky, I.A.; Simkin, B.; Broh-Kahn, R.H. The inactivation of insulin by tissue extracts. VI. The existence, distribution and properties of an insulinase inhibitor. Arch. Biochem. 1950, 28, 415–423.

- Mirsky, I.A.; Perisutti, G.; Diengott, D. Effect of insulinase-inhibitor on destruction of insulin by intact mouse. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1955, 88, 76–78.

- Mirsky, I.A.; Perisutti, G.; Jinks, R. The destruction of insulin by intact mice. Endocrinology 1955, 56, 484–488, doi:10.1210/endo-56-4-484.

- Brush, J.S.; Shah, R.J. Purification and characterization of inhibitors of insulin specific protease in human serum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973, 53, 894–903, doi:10.1016/0006-291x(73)90176-9.

- Ogawa, W.; Shii, K.; Yonezawa, K.; Baba, S.; Yokono, K. Affinity purification of insulin-degrading enzyme and its endoge-nous inhibitor from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 1310–1316.

- McKenzie, R.A.; Burghen, G.A. Partial purification and characterization of insulin protease and its intracellular inhibitor from rat liver. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984, 229, 604–611, doi:10.1016/0003-9861(84)90193-0.

- Ryan, M.P.; Duckworth, W.C. Partial characterization of an endogenous inhibitor of a calcium-dependent form of insulin protease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 116, 195–203, doi:10.1016/0006-291x(83)90400-x.

- Saric, T.; Müller, D.; Seitz, H.J.; Pavelic, K. Non-covalent interaction of ubiquitin with insulin-degrading enzyme. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 204, 11–20, doi:10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00154-0.

- Mirsky, I.A. The hypoglycemic action of insulinase-inhibitors by mouth in patients with diabetes mellitus. Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 1956, 69, 262–275.

- News of Science. Science 1956, 123, 258–262, doi:10.1126/science.123.3190.258.

- Mering, J.; Minkowski, O. Diabetes mellitus nach Pankreasexstirpation. Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1890, 26, 371–387.

- Banting, F.G.; Best, C.H.; Collip, J.B.; Campbell, W.R.; Fletcher, A.A. Pancreatic Extracts in the Treatment of Diabetes Melli-tus. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1922, 12, 141–146.

- Mirsky, I.A. Insulinase. Diabetes 1957, 6, 448–449, doi:10.2337/diab.6.5.448.

- Duckworth, W.C. Insulin degradation: Mechanisms, products, and significance. Endocr. Rev. 1988, 9, 319–345, doi:10.1210/edrv-9-3-319.

- Duckworth, W.C.; Bennett, R.G.; Hamel, F.G. Insulin degradation: Progress and potential. Endocr. Rev. 1998, 19, 608–624, doi:10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349.

- Manolopoulou, M.; Guo, Q.; Malito, E.; Schilling, A.B.; Tang, W.J. Molecular basis of catalytic chamber-assisted unfolding and cleavage of human insulin by human insulin-degrading enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14177–14188, doi:10.1074/jbc.M900068200.

- Grasso, G.; Rizzarelli, E.; Spoto, G. AP/MALDI-MS complete characterization of the proteolytic fragments produced by the interaction of insulin degrading enzyme with bovine insulin. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1590–1598, doi:10.1002/jms.1348.

- Duckworth, W.C.; Heinemann, M.A.; Kitabchi, A.E. Purification of insulin-specific protease by affinity chromatography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1972, 69, 3698–3702.

- Misbin, R.I.; Almira, E.C.; Duckworth, W.C.; Mehl, T.D. Inhibition of insulin degradation by insulin-like growth factors. En-docrinology 1983, 113, 1525–1527, doi:10.1210/endo-113-4-1525.

- Authier, F.; Bergeron, J.J.; Ou, W.J.; Rachubinski, R.A.; Posner, B.I.; Walton, P.A. Degradation of the cleaved leader peptide of thiolase by a peroxisomal proteinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3859–3863, doi:10.1073/pnas.92.9.3859.

- Frank, B.H.; Peavy, D.E.; Hooker, C.S.; Duckworth, W.C. Receptor binding properties of monoiodotyrosyl insulin isomers purified by high performance liquid chromatography. Diabetes 1983, 32, 705–711, doi:10.2337/diab.32.8.705.

- Ryan, M.P.; Duckworth, W.C. Insulin degradation: Assays and enzymes. In The Insulin Receptor; Kahn, C., Harrison, L., Eds.; Alan R Liss Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 29–57.

- Song, E.S.; Mukherjee, A.; Juliano, M.A.; Pyrek, J.S.; Goodman, J.P., Jr.; Juliano, L.; Hersh, L.B. Analysis of the subsite speci-ficity of rat insulysin using fluorogenic peptide substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 1152–1155, doi:10.1074/jbc.M008702200.

- Fosam, A.; Sikder, S.; Abel, B.S.; Tella, S.H.; Walter, M.F.; Mari, A.; Muniyappa, R. Reduced Insulin Clearance and Insu-lin-Degrading Enzyme Activity Contribute to Hyperinsulinemia in African Americans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e1835–e1846, doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa070.

- Song, E.S.; Hersh, L.B. Insulysin: An allosteric enzyme as a target for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 201–206, doi:10.1385/jmn:25:3:201.

- Song, E.S.; Juliano, M.A.; Juliano, L.; Fried, M.G.; Wagner, S.L.; Hersh, L.B. ATP effects on insulin-degrading enzyme are mediated primarily through its triphosphate moiety. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 54216–54220, doi:10.1074/jbc.M411177200.

- Im, H.; Manolopoulou, M.; Malito, E.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Neant-Fery, M.; Sun, C.Y.; Meredith, S.C.; Sisodia, S.S.; Leissring, M.A.; et al. Structure of substrate-free human insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) and biophysical analysis of ATP-induced con-formational switch of IDE. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25453–25463, doi:10.1074/jbc.M701590200.

- Cabrol, C.; Huzarska, M.A.; Dinolfo, C.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Reinstatler, L.; Ni, J.; Yeh, L.A.; Cuny, G.D.; Stein, R.L.; Selkoe, D.J.; et al. Small-molecule activators of insulin-degrading enzyme discovered through high-throughput compound screening. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5274, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005274.

- Song, E.S.; Juliano, M.A.; Juliano, L.; Hersh, L.B. Substrate activation of insulin-degrading enzyme (insulysin). A potential target for drug development. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 49789–49794, doi:10.1074/jbc.M308983200.

- Leissring, M.A.; Lu, A.; Condron, M.M.; Teplow, D.B.; Stein, R.L.; Farris, W.; Selkoe, D.J. Kinetics of amyloid beta-protein degradation determined by novel fluorescence- and fluorescence polarization-based assays. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37314–37320, doi:10.1074/jbc.M305627200.

- Suire, C.N.; Lane, S.; Leissring, M.A. Development and Characterization of Quantitative, High-Throughput-Compatible Assays for Proteolytic Degradation of Glucagon. SLAS Discov. 2018, 23, 1060–1069, doi:10.1177/2472555218786509.

- Suire, C.N.; Brizuela, M.K.; Leissring, M.A. Quantitative, High-Throughput Assays for Proteolytic Degradation of Amylin. Methods Protoc. 2020, 3, 81, doi:10.3390/mps3040081.

- Clot, J.P.; Janicot, M.; Fouque, F.; Desbuquois, B.; Haumont, P.Y.; Lederer, F. Characterization of insulin degradation prod-ucts generated in liver endosomes: In vivo and in vitro studies. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1990, 72, 175–185, doi:10.1016/0303-7207(90)90142-u.

- Hamel, F.G.; Posner, B.I.; Bergeron, J.J.; Frank, B.H.; Duckworth, W.C. Isolation of insulin degradation products from endo-somes derived from intact rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 6703–6708.

- Seabright, P.J.; Smith, G.D. The characterization of endosomal insulin degradation intermediates and their sequence of pro-duction. Biochem. J. 1996, 320 Pt 3, 947–956.

- Authier, F.; Metioui, M.; Fabrega, S.; Kouach, M.; Briand, G. Endosomal proteolysis of internalized insulin at the C-terminal region of the B chain by cathepsin D. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9437–9446, doi:10.1074/jbc.M110188200.

- Kouach, M.; Desbuquois, B.; Authier, F. Endosomal proteolysis of internalised [ArgA0]-human insulin at neutral pH gener-ates the mature insulin peptide in rat liver in vivo. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2621–2632, doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1551-0.

- Authier, F.; Posner, B.I.; Bergeron, J.J. Endosomal proteolysis of internalized proteins. FEBS Lett. 1996, 389, 55–60, doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00368-7.

- Authier, F.; Posner, B.I.; Bergeron, J.J. Insulin-degrading enzyme. Clin. Investig. Med. 1996, 19, 149–160.

- Shen, Y.; Joachimiak, A.; Rosner, M.R.; Tang, W.J. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature 2006, 443, 870–874, doi:10.1038/nature05143.

- Stefanidis, L.; Fusco, N.D.; Cooper, S.E.; Smith-Carpenter, J.E.; Alper, B.J. Molecular Determinants of Substrate Specificity in Human Insulin-Degrading Enzyme. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 4903–4914, doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00474.

- Affholter, J.A.; Cascieri, M.A.; Bayne, M.L.; Brange, J.; Casaretto, M.; Roth, R.A. Identification of residues in the insulin mol-ecule important for binding to insulin-degrading enzyme. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 7727–7733, doi:10.1021/bi00485a022.

- Schäffer, L. A model for insulin binding to the insulin receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 221, 1127–1132, doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18833.x.

- Kristensen, C.; Kjeldsen, T.; Wiberg, F.C.; Schäffer, L.; Hach, M.; Havelund, S.; Bass, J.; Steiner, D.F.; Andersen, A.S. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12978–12983, doi:10.1074/jbc.272.20.12978.

- De Meyts, P. Insulin/receptor binding: The last piece of the puzzle? What recent progress on the structure of the insu-lin/receptor complex tells us (or not) about negative cooperativity and activation. BioEssays 2015, 37, 389–397, doi:10.1002/bies.201400190.

- Macháčková, K.; Mlčochová, K.; Potalitsyn, P.; Hanková, K.; Socha, O.; Buděšínský, M.; Muždalo, A.; Lepšík, M.; Černeková, M.; Radosavljević, J.; et al. Mutations at hypothetical binding site 2 in insulin and insulin-like growth factors 1 and 2 result in receptor- and hormone-specific responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 17371–17382, doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.010072.

- Affholter, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Francke, U.; Roth, R.A. Insulin-degrading enzyme: Stable expression of the human complemen-tary DNA, characterization of its protein product, and chromosomal mapping of the human and mouse genes. Mol. Endo-crinol. 1990, 4, 1125–1135, doi:10.1210/mend-4-8-1125.

- Kuo, W.L.; Gehm, B.D.; Rosner, M.R. Regulation of insulin degradation: Expression of an evolutionarily conserved insu-lin-degrading enzyme increases degradation via an intracellular pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991, 5, 1467–1476, doi:10.1210/mend-5-10-1467.

- Kuo, W.L.; Gehm, B.D.; Rosner, M.R. Cloning and expression of the cDNA for a Drosophila insulin-degrading enzyme. Mol. Endocrinol. 1990, 4, 1580–1591, doi:10.1210/mend-4-10-1580.

- Kuo, W.L.; Gehm, B.D.; Rosner, M.R.; Li, W.; Keller, G. Inducible expression and cellular localization of insulin-degrading enzyme in a stably transfected cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 22599–22606.

- Gehm, B.D.; Rosner, M.R. Regulation of insulin, epidermal growth factor, and transforming growth factor-alpha levels by growth factor-degrading enzymes. Endocrinology 1991, 128, 1603–1610, doi:10.1210/endo-128-3-1603.

- Kayalar, C.; Wong, W.T. Metalloendoprotease inhibitors which block the differentiation of L6 myoblasts inhibit insulin deg-radation by the endogenous insulin-degrading enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 8928–8934.

- Kayalar, C.; Wong, W.T.; Hendrickson, L. Differentiation of BC3H1 and primary skeletal muscle cells and the activity of their endogenous insulin-degrading enzyme are inhibited by the same metalloendoprotease inhibitors. J. Cell. Biochem. 1990, 44, 137–151, doi:10.1002/jcb.240440303.

- Shii, K.; Roth, R.A. Inhibition of insulin degradation by hepatoma cells after microinjection of monoclonal antibodies to a specific cytosolic protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4147–4151, doi:10.1073/pnas.83.12.4147.

- Fawcett, J.; Permana, P.A.; Levy, J.L.; Duckworth, W.C. Regulation of protein degradation by insulin-degrading enzyme: Analysis by small interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 468, 128–133, doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.019.

- Louie, S.; Lakkyreddy, J.; Castellano, B.M.; Haley, B.; Dang, A.N.; Lam, C.; Tang, D.; Lang, S.; Snedecor, B.; Misaghi, S. Insu-lin Degrading Enzyme (IDE) Expressed by Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) Cells Is Responsible for Degradation of Insulin in Culture Media. J. Biotechnol. 2020, doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.04.016.

- Farris, W.; Mansourian, S.; Chang, Y.; Lindsley, L.; Eckman, E.A.; Frosch, M.P.; Eckman, C.B.; Tanzi, R.E.; Selkoe, D.J.; Guenette, S. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4162–4167, doi:10.1073/pnas.0230450100.

- Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Leissring, M.A. Insulin-degrading enzyme is exported via an unconventional protein secretion pathway. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009, 4, 4, doi:10.1186/1750-1326-4-4.

- Song, E.S.; Rodgers, D.W.; Hersh, L.B. Insulin-degrading enzyme is not secreted from cultured cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2335, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20597-6.

- Abdul-Hay, S.O.; Kang, D.; McBride, M.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Leissring, M.A. Deletion of insulin-degrading enzyme elicits antipo-dal, age-dependent effects on glucose and insulin tolerance. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20818, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020818.

- Miller, B.C.; Eckman, E.A.; Sambamurti, K.; Dobbs, N.; Chow, K.M.; Eckman, C.B.; Hersh, L.B.; Thiele, D.L. Amyloid-beta peptide levels in brain are inversely correlated with insulysin activity levels in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6221–6226, doi:10.1073/pnas.1031520100.

- Steneberg, P.; Bernardo, L.; Edfalk, S.; Lundberg, L.; Backlund, F.; Ostenson, C.G.; Edlund, H. The type 2 diabetes-associated gene ide is required for insulin secretion and suppression of alpha-synuclein levels in beta-cells. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2004–2014.

- Villa-Pérez, P.; Merino, B.; Fernandez-Diaz, C.M.; Cidad, P.; Lobaton, C.D.; Moreno, A.; Muturi, H.T.; Ghadieh, H.E.; Najjar, S.M.; Leissring, M.A.; et al. Liver-specific ablation of insulin-degrading enzyme causes hepatic insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, without affecting insulin clearance in mice. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2018, 88, 1–11, doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2018.08.001.

- Merino, B.; Fernández-Díaz, C.M.; Parrado-Fernández, C.; González-Casimiro, C.M.; Postigo-Casado, T.; Lobaton, C.D.; Leissring, M.A.; Cózar-Castellano, I.; Perdomo, G. Hepatic insulin-degrading enzyme regulates glucose and insulin homeo-stasis in diet-induced obese mice. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2020, 113, 154352, doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154352.

- Duckworth, W.C. Insulin and glucagon degradation by the kidney. I. Subcellular distribution under different assay condition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1976, 437, 518–530.

- Ciaccio, C.; Tundo, G.R.; Grasso, G.; Spoto, G.; Marasco, D.; Ruvo, M.; Gioia, M.; Rizzarelli, E.; Coletta, M. Somatostatin: A novel substrate and a modulator of insulin-degrading enzyme activity. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 385, 1556–1567, doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.025.

- Bennett, R.G.; Duckworth, W.C.; Hamel, F.G. Degradation of amylin by insulin-degrading enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 36621–36625, doi:10.1074/jbc.M006170200.

- Kurochkin, I.V.; Goto, S. Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide specifically interacts with and is degraded by insulin degrading enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1994, 345, 33–37.

- Edbauer, D.; Willem, M.; Lammich, S.; Steiner, H.; Haass, C. Insulin-degrading enzyme rapidly removes the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD). J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 13389–13393, doi:10.1074/jbc.M111571200.

- Morelli, L.; Llovera, R.E.; Alonso, L.G.; Frangione, B.; de Prat-Gay, G.; Ghiso, J.; Castano, E.M. Insulin-degrading enzyme degrades amyloid peptides associated with British and Danish familial dementia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 332, 808–816, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.020.

- Muller, D.; Schulze, C.; Baumeister, H.; Buck, F.; Richter, D. Rat insulin-degrading enzyme: Cleavage pattern of the natriu-retic peptide hormones ANP, BNP, and CNP revealed by HPLC and mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 11138–11143.

- Tundo, G.R.; Di Muzio, E.; Ciaccio, C.; Sbardella, D.; Di Pierro, D.; Polticelli, F.; Coletta, M.; Marini, S. Multiple allosteric sites are involved in the modulation of insulin-degrading-enzyme activity by somatostatin. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3755–3770, doi:10.1111/febs.13841.