The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) was first identified as the intracellular protein that 14 bound and mediated the toxic effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD, dioxin) and 15 dioxin-like compounds (DLCs). Subsequent studies show that the AhR plays an important role in 16 maintaining cellular homeostasis and in pathophysiology and there is increasing evidence that the 17 AhR is a important drug target. The AhR binds structurally diverse compounds including 18 pharmaceuticals, phytochemicals, endogenous biochemicals some of which may serve as 19 endogenous ligands. Classification of DLCs and non-DLCs based on their persistence (metabolism), 20 toxicities, binding to wild-type/mutant AhR and structural similarities have been reported. This 21 review provides data suggesting that ligands for the AhR are selective AhR modulators (SAhRMs) 22 which exhibit tissue/cell-specific AhR agonist and antagonist activities and their functional diversity 23 is similar to selective receptor modulators that target steroid hormone and other nuclear receptors.

- AhR

- ligand selectivity

- agonist

- antagonist

1. Introduction

Intracellular receptors such as the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily play important roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and in pathophysiology [1,2][1][2]. Members of the steroid hormone receptor subfamily were among the first NR’s identified, and the binding and effects of their endogenous hormonal ligands such as 17β-estradiol have been extensively investigated and form a conceptual basis for understanding hormone-hormone receptor action [3]. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is also an intracellular receptor that is a member of the basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of genes that exhibit a mode of action similar to that described for many NRs [4,5,6][4][5][6]. The cytosolic AhR is bound to several factors, including hsp90, AIP/XAP2 and p23, and treatment with an AhR ligand results in nuclear uptake of the bound receptor complex that forms a nuclear heterodimer with the AhR nuclear translocator (Arnt) protein. This heterodimer interacts with cis-dioxin/xenobiotic response elements (DRE/XRE), which have a core GCGTG pentanucleotide sequence, and this results in recruitment of nuclear cofactors to activate or repress gene expression [4,5,6][4][5][6]. This pathway is similar to that described for several nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, and retinoic acid receptors, which form a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) [1,2][1][2]. These similarities between NRs and the AhR also extend to their increasing number of alternative mechanisms of action, which include binding of receptor complexes to non-consensus response elements; interactions with alternate partners (rather than RXR/Arnt); and acting via extranuclear regions of the cell, including the membrane and cytosol [7,8,9,10,11,12][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Despite the similarities between the AhR and steroid hormone receptors, the AhR was initially identified and characterized as the intracellular receptor not for an endogenous ligand but for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), a toxic industrial and combustion by-product [13]. Some of the evidence demonstrating that the AhR protein was a receptor included studies showing that the rank order binding affinities of TCDD and structurally related dioxin-like compounds (DLCs) were similar to their rank order potencies for inducing specific toxic responses and as inducers of CYP1A1 [13,14][13][14]. Several endogenous ligands that bind the AhR have subsequently been identified, and these include 6-formyl (3,2-b) carbazole (FICZ), 2-(1′-H-indole-3-carbonyl)thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester (ITE), tryptophan metabolites such as kynurenine and other gut microbial products, and leukotrienes [15,16,17,18,19,20][15][16][17][18][19][20]. These compounds exhibit some tissue-specific modulation of AhR action; however, their role as major endogenous AhR ligands is unresolved. The differences in the initial discoveries of steroid hormone receptors and their endogenous hormonal ligands vs. the AhR receptor, and its high-affinity ligand, TCDD, has tarred the AhR as the receptor associated with toxicity and DLCs. This linkage between the AhR and toxicity has hindered the development of drugs targeting the AhR, whereas up to 13.5% of all developed drugs target NRs [21].

2. AhR Functions and Potential for Drug Targeting

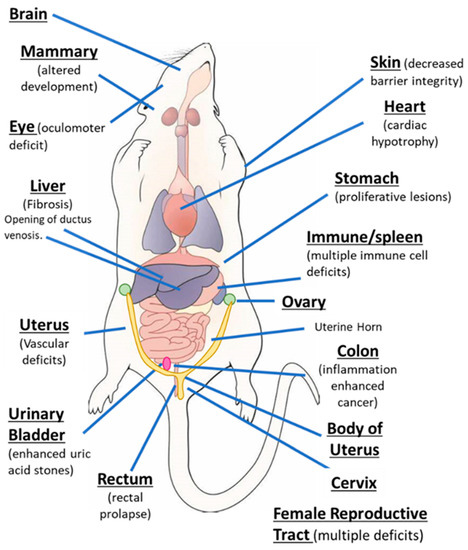

AhR knockout mice (AhR−/−) were generated by several laboratories, and initial studies confirmed that the receptor was required for mediating the toxicity of TCDD and structurally related halogenated aromatics, including polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans and biphenyls [22,23,24,25,26,27][22][23][24][25][26][27]. Comparable studies with Arnt knockout mice could not be performed, since the loss of Arnt was embryonal lethal [28]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the loss of the AhR in mice resulted in several abnormalities in multiple organs/tissues, which include liver (fibrosis, failure of developmental closure of the ductus venosis) [29]; heart (cardiac hypertrophy, elevated arterial blood pressure and increased fibrosis) [30,31,32,33,34][30][31][32][33][34]; multiple adverse female reproductive tract problems [35,36,37,38][35][36][37][38]; altered mammary gland development [39,40][39][40]; decreased skin barrier integrity [41]; decreased intestinal resilience (increased stem cells, increased susceptibility to inflammation, decreased barrier function immune dysfunctions and enhanced tumorigenesis) [42,43,44,45,46,47][42][43][44][45][46][47]; extensive immune dysfunctions [48,49,50,51,52,53][48][49][50][51][52][53]; modulation of stem cells [42,54,55][42][54][55]; enhanced formation of uric acid stones in the bladder [56]; oculomotor deficits and defective optic nerve myelin sheath [57,58][57][58]; and neuronal function deficits [59,60,61][59][60][61]. These results from mouse models demonstrate that although loss of the AhR in mice is not embryo-lethal, this receptor plays a role in multiple organs/tissues (Figure 1).

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) plays a role in cellular homeostasis in several tissues/organs in the mouse models.

The potential utility of a receptor as a drug target depends on at least two critical factors, namely, that the receptor is expressed (or overexpressed) and has important functions in a diseased target tissue. There are distinct advantages in targeting a receptor. If the functional activity of the receptor enhances or inhibits the disease process then potential receptor ligand therapies include treatment with antagonists or agonists, respectively. There is extensive evidence that the AhR is expressed and functional in multiple tumors, including pancreatic, breast, lung, colon, glioma and other cancer cell lines (rev in [62,63][62][63]). For example, knockdown of the AhR in head and neck cancer cells decreases invasion and expression of growth-promoting genes such as amphiregulin, epiregulin and platelet derived growth factor A, demonstrating the pro-oncogenic activity of the AhR. Thus, treatment of these cells with an agonist (TCDD) or the AhR antagonist GNF351 enhances or inhibits, respectively, the pro-oncogenic activity of the AhR [64,65,66,67,68,69][64][65][66][67][68][69]. In intestinal cancer, the loss of the AhR enhances carcinogenesis in mouse models and treatment of wild-type mice with AhR agonists protects against chemical-induced and genetic models of colon cancer [42,43,44,45,46,47][42][43][44][45][46][47]. Studies in this laboratory also showed that the AhR exhibited tumor suppressor-like activity in glioblastoma cells [67]. This was in contrast to a previous report [68], and there are other examples of apparent differences in the functional roles of the AhR in other tumor types. The AhR plays a role in other tumors, and in some cases, the variability in the function of the AhR is due to the use of different model systems.

References

- Evans, R.M. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A rosetta stone for physiology. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambon, P. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A personal retrospect on the first two decades. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.; Santen, R.J. Celebrating 75 years of oestradiol. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 55, T1–T20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilla, M.N.; Malecki, K.M.C.; Hahn, M.E.; Wilson, R.H.; Bradfield, C.A. The Ah Receptor: Adaptive Metabolism, Ligand Diversity, and the Xenokine Model. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 860–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.V.; Bradfield, C.A. Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996, 12, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beischlag, T.V.; Morales, J.L.; Hollingshead, B.D.; Perdew, G.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2008, 18, 207–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Elferink, C.J. A novel nonconsensus xenobiotic response element capable of mediating aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 81, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.R.; Joshi, A.D.; Elferink, C.J. The tumor suppressor Kruppel-like factor 6 is a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor DNA binding partner. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 345, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.F.; Sciullo, E.; Li, W.; Wong, P.; Lazennec, G.; Matsumura, F. RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 2941–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.P.; Joshi, A.D.; Elferink, C.J. Ah Receptor Pathway Intricacies; Signaling Through Diverse Protein Partners and DNA-Motifs. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 4, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.R. Extranuclear steroid receptors are essential for steroid hormone actions. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, S.; Kim, K. Non-classical genomic estrogen receptor (ER)/specificity protein and ER/activating protein-1 signaling pathways. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 41, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, A.; Glover, E.; Kende, A.S. Stereospecific, high affinity binding of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by hepatic cytosol. Evidence that the binding species is receptor for induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 4936–4946. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, A.; Knutson, J.C. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons: Examination of the mechanism of toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1982, 22, 517–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannug, A.; Rannug, U.; Rosenkranz, H.S.; Winqvist, L.; Westerholm, R.; Agurell, E.; Grafstrom, A.K. Certain photooxidized derivatives of tryptophan bind with very high affinity to the Ah receptor and are likely to be endogenous signal substances. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 15422–15427. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Clagett-Dame, M.; Peterson, R.E.; Hahn, M.E.; Westler, W.M.; Sicinski, R.R.; DeLuca, H.F. A ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor isolated from lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14694–14699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, C.R.; Morales, J.L.; Prabhu, K.S.; Perdew, G.H. Leukotriene A4 metabolites are endogenous ligands for the Ah receptor. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 8445–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelante, T.; Iannitti, R.G.; Cunha, C.; De Luca, A.; Giovannini, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Zecchi, R.; D’Angelo, C.; Massi-Benedetti, C.; Fallarino, F.; et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, S.; Toshimitsu, T.; Matsuoka, S.; Maruyama, A.; Oh-Oka, K.; Takamura, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishimaru, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Ikegami, S.; et al. Identification of a probiotic bacteria-derived activator of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor that inhibits colitis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2014, 92, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexia, N.; Gaitanis, G.; Velegraki, A.; Soshilov, A.; Denison, M.S.; Magiatis, P. Pityriazepin and other potent AhR ligands isolated from Malassezia furfur yeast. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 571, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Ursu, O.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Donadi, R.S.; Bologa, C.G.; Karlsson, A.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hersey, A.; Oprea, T.I.; et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Pineau, T.; Hilbert, D.M.; McPhail, T.; Lee, S.S.; Kimura, S.; Nebert, D.W.; Rudikoff, S.; Ward, J.M.; Gonzalez, F.J. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science 1995, 268, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.V.; Su, G.H.; Reddy, J.K.; Simon, M.C.; Bradfield, C.A. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: Involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6731–6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, J.; Yamashita, K.; Nakamura, K.; Morita, M.; Takagi, T.N.; Nakao, K.; Ema, M.; Sogawa, K.; Yasuda, M.; Katsuki, M.; et al. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells 1997, 2, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, F.J.; Fernandez-Salguero, P. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Studies using the AHR-null mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1998, 26, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Lahvis, G.P.; Bradfield, C.A. Ahr null alleles: Distinctive or different? Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 56, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Salguero, P.M.; Ward, J.M.; Sundberg, J.P.; Gonzalez, F.J. Lesions of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Vet. Pathol. 1997, 34, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, K.R.; Abbott, B.; Hankinson, O. ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev. Biol. 1997, 191, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahvis, G.P.; Pyzalski, R.W.; Glover, E.; Pitot, H.C.; McElwee, M.K.; Bradfield, C.A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is required for developmental closure of the ductus venosus in the neonatal mouse. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.K.; Goens, M.B.; Nunez, B.A.; Walker, M.K. Characterizing the role of endothelin-1 in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy in aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) null mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 212, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.K.; Goens, M.B.; Kanagy, N.L.; Walker, M.K. Cardiac hypertrophy in aryl hydrocarbon receptor null mice is correlated with elevated angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and mean arterial blood pressure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003, 193, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauzeau, V.; Carvajal-Gonzalez, J.M.; Riolobos, A.S.; Sevilla, M.A.; Menacho-Marquez, M.; Roman, A.C.; Abad, A.; Montero, M.J.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Bustelo, X.R. Transcriptional factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) controls cardiovascular and respiratory functions by regulating the expression of the Vav3 proto-oncogene. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2896–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, A.K.; Peterson, S.L.; Timmins, G.S.; Walker, M.K. Endothelin-1-mediated increase in reactive oxygen species and NADPH Oxidase activity in hearts of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) null mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 88, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichihara, S.; Li, P.; Mise, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Izuoka, K.; Nakajima, T.; Gonzalez, F.; Ichihara, G. Ablation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis through enhanced c-Jun/HIF-1alpha signaling. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, T.; Mimura, J.; Nakamura, N.; Harada, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Morohashi, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y. Intrinsic function of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor as a key factor in female reproduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 10040–10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, J.C.; Lin, T.M.; Loeffler, I.K.; Peterson, R.E.; Flaws, J.A. Physiological role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mouse ovary development. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 56, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, J.C.; Miller, K.P.; Lin, T.M.; Greenfeld, C.; Babus, J.K.; Peterson, R.E.; Flaws, J.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates growth, but not atresia, of mouse preantral and antral follicles. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.D.; Schmid, J.E.; Pitt, J.A.; Buckalew, A.R.; Wood, C.R.; Held, G.A.; Diliberto, J.J. Adverse reproductive outcomes in the transgenic Ah receptor-deficient mouse. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 155, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, B.J.; Manickam, R.; Lawrence, B.P. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor during pregnancy in the mouse alters mammary development through direct effects on stromal and epithelial tissues. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 84, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hushka, L.J.; Williams, J.S.; Greenlee, W.F. Characterization of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran-dependent suppression and AH receptor pathway gene expression in the developing mouse mammary gland. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1998, 152, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.; Weighardt, H.; Deenen, R.; Kohrer, K.; Clausen, B.; Zahner, S.; Boukamp, P.; Bloch, W.; Krutmann, J.; Esser, C. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Keratinocytes Is Essential for Murine Skin Barrier Integrity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 2260–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metidji, A.; Omenetti, S.; Crotta, S.; Li, Y.; Nye, E.; Ross, E.; Li, V.; Maradana, M.R.; Schiering, C.; Stockinger, B. The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity. Immunity 2018, 49, 353–362.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Qiu, J.; Bostick, J.W.; Ueda, A.; Schjerven, H.; Li, S.; Jobin, C.; Chen, Z.E.; Zhou, L. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Preferentially Marks and Promotes Gut Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2277–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Xiao, W.; Xu, P.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation Modulates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function by Maintaining Tight Junction Integrity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawajiri, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ohtake, F.; Ikuta, T.; Matsushima, Y.; Mimura, J.; Pettersson, S.; Pollenz, R.S.; Sakaki, T.; Hirokawa, T.; et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor suppresses intestinal carcinogenesis in ApcMin/+ mice with natural ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13481–13486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Diaz, C.J.; Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S.M.; Nukaya, M.; Geiger, P.G.; Balbo, S.; Dator, R.; Megna, B.W.; Carney, P.R.; Bradfield, C.A.; Kennedy, G.D. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor is a Repressor of Inflammation-associated Colorectal Tumorigenesis in Mouse. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furumatsu, K.; Nishiumi, S.; Kawano, Y.; Ooi, M.; Yoshie, T.; Shiomi, Y.; Kutsumi, H.; Ashida, H.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Azuma, T.; et al. A role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in attenuation of colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 2532–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhoen, M.; Hirota, K.; Westendorf, A.M.; Buer, J.; Dumoutier, L.; Renauld, J.C.; Stockinger, B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 2008, 453, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S.; Iglesias, A.H.; Korn, T.; Farez, M.F.; Bettelli, E.; Caccamo, M.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, C.; Rannug, A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in barrier organ physiology, immunology, and toxicology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, B.; Di Meglio, P.; Gialitakis, M.; Duarte, J.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Multitasking in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.B.; Kerkvliet, N.I. Dioxin and immune regulation: Emerging role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the generation of regulatory T cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1183, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Puga, A. Dioxin exposure disrupts the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 115, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Garrett, R.W.; Casado, F.L.; Gasiewicz, T.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-null allele mice have hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells with abnormal characteristics and functions. Stem. Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Inzunza, J.; Suzuki, H.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.A. Uric acid stones in the urinary bladder of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, A.; Mialot, A.; Petit, J.M.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Barouki, R.; Coumoul, X.; Beraneck, M. Oculomotor deficits in aryl hydrocarbon receptor null mouse. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juricek, L.; Carcaud, J.; Pelhaitre, A.; Riday, T.T.; Chevallier, A.; Lanzini, J.; Auzeil, N.; Laprevote, O.; Dumont, F.; Jacques, S.; et al. AhR-deficiency as a cause of demyelinating disease and inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, D.P.; Adham, Z.O.; Thompson, B.; Genestine, M.; Cherry, J.; Olschowka, J.A.; DiCicco-Bloom, E.; Opanashuk, L.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor deletion in cerebellar granule neuron precursors impairs neurogenesis. Dev. Neurobiol. 2016, 76, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chang, L.H.; Huang, S.S.; Huang, Y.J.; Chih, C.L.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, I.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulates stroke-induced astrogliosis and neurogenesis in the adult mouse brain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chou, C.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Hung, C.C.; Chen, J.Y.; Chang, H.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Yeh, G.C.; Lee, Y.H. Knockdown of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor attenuates excitotoxicity and enhances NMDA-induced BDNF expression in cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 2009, 111, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, I.A.; Patterson, A.D.; Perdew, G.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands in cancer: Friend and foe. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolluri, S.K.; Jin, U.H.; Safe, S. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in carcinogenesis and potential as an anti-cancer drug target. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2497–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNatale, B.C.; Schroeder, J.C.; Perdew, G.H. Ah receptor antagonism inhibits constitutive and cytokine inducible IL6 production in head and neck tumor cell lines. Mol. Carcinog. 2011, 50, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNatale, B.C.; Smith, K.; John, K.; Krishnegowda, G.; Amin, S.G.; Perdew, G.H. Ah receptor antagonism represses head and neck tumor cell aggressive phenotype. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Lahoti, T.S.; Wagner, K.; Hughes, J.M.; Perdew, G.H. The Ah receptor regulates growth factor expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Carcinog. 2014, 53, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, U.H.; Karki, K.; Cheng, Y.; Michelhaugh, S.K.; Mittal, S.; Safe, S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a tumor suppressor-like gene in glioblastoma. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11342–11353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, C.A.; Litzenburger, U.M.; Sahm, F.; Ott, M.; Tritschler, I.; Trump, S.; Schumacher, T.; Jestaedt, L.; Schrenk, D.; Weller, M.; et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2011, 478, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

References

- Evans, R.M. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A rosetta stone for physiology. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1429–1438, doi:10.1210/me.2005-0046.

- Chambon, P. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A personal retrospect on the first two decades. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1418–1428, doi:10.1210/me.2005-0125.

- Simpson, E.; Santen, R.J. Celebrating 75 years of oestradiol. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 55, T1–T20, doi:10.1530/JME-15-0128.

- Avilla, M.N.; Malecki, K.M.C.; Hahn, M.E.; Wilson, R.H.; Bradfield, C.A. The Ah Receptor: Adaptive Metabolism, Ligand Diversity, and the Xenokine Model. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 860–879, doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00476.

- Schmidt, J.V.; Bradfield, C.A. Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996, 12, 55–89, doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.55.

- Beischlag, T.V.; Luis Morales, J.; Hollingshead, B.D.; Perdew, G.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2008, 18, 207–250.

- Huang, G.; Elferink, C.J. A novel nonconsensus xenobiotic response element capable of mediating aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 81, 338–347, doi:10.1124/mol.111.075952.

- Wilson, S.R.; Joshi, A.D.; Elferink, C.J. The tumor suppressor Kruppel-like factor 6 is a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor DNA binding partner. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 345, 419–429, doi:10.1124/jpet.113.203786.

- Vogel, C.F.; Sciullo, E.; Li, W.; Wong, P.; Lazennec, G.; Matsumura, F. RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 2941–2955, doi:10.1210/me.2007-0211.

- Jackson, D.P.; Joshi, A.D.; Elferink, C.J. Ah Receptor Pathway Intricacies; Signaling Through Diverse Protein Partners and DNA-Motifs. Toxicol. Res. (Camb) 2015, 4, 1143–1158.

- Levin, E.R. Extranuclear steroid receptors are essential for steroid hormone actions. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 271–280, doi:10.1146/annurev-med-050913-021703.

- Safe, S.; Kim, K. Non-classical genomic estrogen receptor (ER)/specificity protein and ER/activating protein-1 signaling pathways. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 41, 263–275, doi:10.1677/JME-08-0103.

- Poland, A.; Glover, E.; Kende, A.S. Stereospecific, high affinity binding of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by hepatic cytosol. Evidence that the binding species is receptor for induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 4936–4946.

- Poland, A.; Knutson, J.C. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons: Examination of the mechanism of toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1982, 22, 517–554, doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.002505.

- Rannug, A.; Rannug, U.; Rosenkranz, H.S.; Winqvist, L.; Westerholm, R.; Agurell, E.; Grafstrom, A.K. Certain photooxidized derivatives of tryptophan bind with very high affinity to the Ah receptor and are likely to be endogenous signal substances. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 15422–15427.

- Song, J.; Clagett-Dame, M.; Peterson, R.E.; Hahn, M.E.; Westler, W.M.; Sicinski, R.R.; DeLuca, H.F. A ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor isolated from lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14694–14699, doi:10.1073/pnas.232562899.

- Chiaro, C.R.; Morales, J.L.; Prabhu, K.S.; Perdew, G.H. Leukotriene A4 metabolites are endogenous ligands for the Ah receptor. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 8445–8455, doi:10.1021/bi800712f.

- Zelante, T.; Iannitti, R.G.; Cunha, C.; De Luca, A.; Giovannini, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Zecchi, R.; D’Angelo, C.; Massi-Benedetti, C.; Fallarino, F.; et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–385, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003.

- Fukumoto, S.; Toshimitsu, T.; Matsuoka, S.; Maruyama, A.; Oh-Oka, K.; Takamura, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishimaru, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Ikegami, S.; et al. Identification of a probiotic bacteria-derived activator of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor that inhibits colitis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2014, 92, 460–465, doi:10.1038/icb.2014.2.

- Mexia, N.; Gaitanis, G.; Velegraki, A.; Soshilov, A.; Denison, M.S.; Magiatis, P. Pityriazepin and other potent AhR ligands isolated from Malassezia furfur yeast. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 571, 16–20, doi:10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.023.

- Santos, R.; Ursu, O.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Donadi, R.S.; Bologa, C.G.; Karlsson, A.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hersey, A.; Oprea, T.I.; et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 19–34, doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.230.

- Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Pineau, T.; Hilbert, D.M.; McPhail, T.; Lee, S.S.; Kimura, S.; Nebert, D.W.; Rudikoff, S.; Ward, J.M.; Gonzalez, F.J. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science 1995, 268, 722–726.

- Schmidt, J.V.; Su, G.H.; Reddy, J.K.; Simon, M.C.; Bradfield, C.A. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: Involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6731–6736, doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6731.

- Mimura, J.; Yamashita, K.; Nakamura, K.; Morita, M.; Takagi, T.N.; Nakao, K.; Ema, M.; Sogawa, K.; Yasuda, M.; Katsuki, M.; et al. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells 1997, 2, 645–654, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1490345.x.

- Gonzalez, F.J.; Fernandez-Salguero, P. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Studies using the AHR-null mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1998, 26, 1194–1198.

- Lahvis, G.P.; Bradfield, C.A. Ahr null alleles: Distinctive or different? Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 56, 781–787, doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00134-8.

- Fernandez-Salguero, P.M.; Ward, J.M.; Sundberg, J.P.; Gonzalez, F.J. Lesions of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Vet. Pathol. 1997, 34, 605–614.

- Kozak, K.R.; Abbott, B.; Hankinson, O. ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev. Biol. 1997, 191, 297–305, doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8758.

- Lahvis, G.P.; Pyzalski, R.W.; Glover, E.; Pitot, H.C.; McElwee, M.K.; Bradfield, C.A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is required for developmental closure of the ductus venosus in the neonatal mouse. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 714–720, doi:10.1124/mol.104.008888.

- Lund, A.K.; Goens, M.B.; Nunez, B.A.; Walker, M.K. Characterizing the role of endothelin-1 in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy in aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) null mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 212, 127–135, doi:10.1016/j.taap.2005.07.005.

- Lund, A.K.; Goens, M.B.; Kanagy, N.L.; Walker, M.K. Cardiac hypertrophy in aryl hydrocarbon receptor null mice is correlated with elevated angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and mean arterial blood pressure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003, 193, 177–187.

- Sauzeau, V.; Carvajal-Gonzalez, J.M.; Riolobos, A.S.; Sevilla, M.A.; Menacho-Marquez, M.; Roman, A.C.; Abad, A.; Montero, M.J.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Bustelo, X.R. Transcriptional factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) controls cardiovascular and respiratory functions by regulating the expression of the Vav3 proto-oncogene. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2896–2909, doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.187534.

- Lund, A.K.; Peterson, S.L.; Timmins, G.S.; Walker, M.K. Endothelin-1-mediated increase in reactive oxygen species and NADPH Oxidase activity in hearts of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) null mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 88, 265–273, doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi284.

- Ichihara, S.; Li, P.; Mise, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Izuoka, K.; Nakajima, T.; Gonzalez, F.; Ichihara, G. Ablation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis through enhanced c-Jun/HIF-1alpha signaling. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1543–1553, doi:10.1007/s00204-019-02446-1.

- Baba, T.; Mimura, J.; Nakamura, N.; Harada, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Morohashi, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y. Intrinsic function of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor as a key factor in female reproduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 10040–10051, doi:10.1128/MCB.25.22.10040-10051.2005.

- Benedict, J.C.; Lin, T.M.; Loeffler, I.K.; Peterson, R.E.; Flaws, J.A. Physiological role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mouse ovary development. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 56, 382–388.

- Benedict, J.C.; Miller, K.P.; Lin, T.M.; Greenfeld, C.; Babus, J.K.; Peterson, R.E.; Flaws, J.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates growth, but not atresia, of mouse preantral and antral follicles. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 1511–1517, doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.007492.

- Abbott, B.D.; Schmid, J.E.; Pitt, J.A.; Buckalew, A.R.; Wood, C.R.; Held, G.A.; Diliberto, J.J. Adverse reproductive outcomes in the transgenic Ah receptor-deficient mouse. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 155, 62–70, doi:10.1006/taap.1998.8601.

- Lew, B.J.; Manickam, R.; Lawrence, B.P. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor during pregnancy in the mouse alters mammary development through direct effects on stromal and epithelial tissues. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 84, 1094–1102, doi:10.1095/biolreprod.110.087544.

- Hushka, L.J.; Williams, J.S.; Greenlee, W.F. Characterization of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran-dependent suppression and AH receptor pathway gene expression in the developing mouse mammary gland. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1998, 152, 200–210, doi:10.1006/taap.1998.8508.

- Haas, K.; Weighardt, H.; Deenen, R.; Kohrer, K.; Clausen, B.; Zahner, S.; Boukamp, P.; Bloch, W.; Krutmann, J.; Esser, C. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Keratinocytes Is Essential for Murine Skin Barrier Integrity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 2260–2269, doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.06.627.

- Metidji, A.; Omenetti, S.; Crotta, S.; Li, Y.; Nye, E.; Ross, E.; Li, V.; Maradana, M.R.; Schiering, C.; Stockinger, B. The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity. Immunity 2018, 49, 353–362 e355, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.010.

- Ye, J.; Qiu, J.; Bostick, J.W.; Ueda, A.; Schjerven, H.; Li, S.; Jobin, C.; Chen, Z.E.; Zhou, L. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Preferentially Marks and Promotes Gut Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2277–2290, doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.114.

- Yu, M.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Xiao, W.; Xu, P.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation Modulates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function by Maintaining Tight Junction Integrity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 69–77, doi:10.7150/ijbs.22259.

- Kawajiri, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ohtake, F.; Ikuta, T.; Matsushima, Y.; Mimura, J.; Pettersson, S.; Pollenz, R.S.; Sakaki, T.; Hirokawa, T.; et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor suppresses intestinal carcinogenesis in ApcMin/+ mice with natural ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13481–13486, doi:10.1073/pnas.0902132106.

- Diaz-Diaz, C.J.; Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S.M.; Nukaya, M.; Geiger, P.G.; Balbo, S.; Dator, R.; Megna, B.W.; Carney, P.R.; Bradfield, C.A.; Kennedy, G.D. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor is a Repressor of Inflammation-associated Colorectal Tumorigenesis in Mouse. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 429–436, doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001874.

- Furumatsu, K.; Nishiumi, S.; Kawano, Y.; Ooi, M.; Yoshie, T.; Shiomi, Y.; Kutsumi, H.; Ashida, H.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Azuma, T.; et al. A role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in attenuation of colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 2532–2544, doi:10.1007/s10620-011-1643-9.

- Veldhoen, M.; Hirota, K.; Westendorf, A.M.; Buer, J.; Dumoutier, L.; Renauld, J.C.; Stockinger, B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 2008, 453, 106–109, doi:10.1038/nature06881.

- Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S.; Iglesias, A.H.; Korn, T.; Farez, M.F.; Bettelli, E.; Caccamo, M.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 65–71, doi:10.1038/nature06880.

- Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.012.

- Esser, C.; Rannug, A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in barrier organ physiology, immunology, and toxicology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 259–279, doi:10.1124/pr.114.009001.

- Stockinger, B.; Di Meglio, P.; Gialitakis, M.; Duarte, J.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Multitasking in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 403–432, doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120245.

- Marshall, N.B.; Kerkvliet, N.I. Dioxin and immune regulation: Emerging role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the generation of regulatory T cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1183, 25–37, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05125.x.

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Puga, A. Dioxin exposure disrupts the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 115, 225–237, doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq038.

- Singh, K.P.; Garrett, R.W.; Casado, F.L.; Gasiewicz, T.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-null allele mice have hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells with abnormal characteristics and functions. Stem. Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 769–784, doi:10.1089/scd.2010.0333.

- Butler, R.; Inzunza, J.; Suzuki, H.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.A. Uric acid stones in the urinary bladder of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1122–1126, doi:10.1073/pnas.1120581109.

- Chevallier, A.; Mialot, A.; Petit, J.M.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Barouki, R.; Coumoul, X.; Beraneck, M. Oculomotor deficits in aryl hydrocarbon receptor null mouse. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53520, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053520.

- Juricek, L.; Carcaud, J.; Pelhaitre, A.; Riday, T.T.; Chevallier, A.; Lanzini, J.; Auzeil, N.; Laprevote, O.; Dumont, F.; Jacques, S.; et al. AhR-deficiency as a cause of demyelinating disease and inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9794, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09621-3.

- Dever, D.P.; Adham, Z.O.; Thompson, B.; Genestine, M.; Cherry, J.; Olschowka, J.A.; DiCicco-Bloom, E.; Opanashuk, L.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor deletion in cerebellar granule neuron precursors impairs neurogenesis. Dev. Neurobiol. 2016, 76, 533–550, doi:10.1002/dneu.22330.

- Chen, W.C.; Chang, L.H.; Huang, S.S.; Huang, Y.J.; Chih, C.L.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, I.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulates stroke-induced astrogliosis and neurogenesis in the adult mouse brain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 187, doi:10.1186/s12974-019-1572-7.

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chou, C.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Hung, C.C.; Chen, J.Y.; Chang, H.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Yeh, G.C.; Lee, Y.H. Knockdown of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor attenuates excitotoxicity and enhances NMDA-induced BDNF expression in cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 2009, 111, 777–789, doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06364.x.

- Murray, I.A.; Patterson, A.D.; Perdew, G.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands in cancer: Friend and foe. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 801–814, doi:10.1038/nrc3846.

- Kolluri, S.K.; Jin, U.H.; Safe, S. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in carcinogenesis and potential as an anti-cancer drug target. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2497–2513, doi:10.1007/s00204-017-1981-2.

- DiNatale, B.C.; Schroeder, J.C.; Perdew, G.H. Ah receptor antagonism inhibits constitutive and cytokine inducible IL6 production in head and neck tumor cell lines. Mol. Carcinog. 2011, 50, 173–183, doi:10.1002/mc.20702.

- DiNatale, B.C.; Smith, K.; John, K.; Krishnegowda, G.; Amin, S.G.; Perdew, G.H. Ah receptor antagonism represses head and neck tumor cell aggressive phenotype. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 1369–1379, doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0216.

- John, K.; Lahoti, T.S.; Wagner, K.; Hughes, J.M.; Perdew, G.H. The Ah receptor regulates growth factor expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Carcinog. 2014, 53, 765–776, doi:10.1002/mc.22032.

- Jin, U.H.; Karki, K.; Cheng, Y.; Michelhaugh, S.K.; Mittal, S.; Safe, S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a tumor suppressor-like gene in glioblastoma. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11342–11353, doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.008882.

- Opitz, C.A.; Litzenburger, U.M.; Sahm, F.; Ott, M.; Tritschler, I.; Trump, S.; Schumacher, T.; Jestaedt, L.; Schrenk, D.; Weller, M.; et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2011, 478, 197–203, doi:10.1038/nature10491.

- Kawai, S.; Iijima, H.; Shinzaki, S.; Hiyama, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Araki, M.; Iwatani, S.; Shiraishi, E.; Mukai, A.; Inoue, T.; et al. Indigo Naturalis ameliorates murine dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis via aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 904–919, doi:10.1007/s00535-016-1292-z.