Overlying gastrointestinal epithelial cells is the transparent mucus layer that separates the lumen from the host. The dynamic mucus layer serves to lubricate the mucosal surface, to protect under-lying epithelial cells, and as a transport medium between luminal contents and epithelial cells. Furthermore, it provides a habitat for commensal bacteria and signals to the underlying immune system. Mucins are highly glycosylated proteins, and their glycocode is tissue-specific and closely linked to the resident microbiota.

- microbiota

- intestinal mucus

- microbe–mucus interactions

1. The Intestinal Mucus Layer: Our Knight in Slimy Armor

1.1. Mucus Layer Structure and Composition

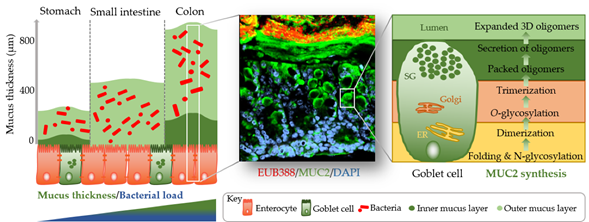

The identification of methods to visualize and measure mucus allowed for intensive study of the previously overlooked and mostly underappreciated protective layer. Groundbreaking in the understanding of the intestinal mucus layer structure was the development of in vivo mucus thickness measurements in animals [1][7], which were later followed by ex vivo mucus thickness measurements in human and mouse tissues [2][8]. Mucus forms a complex viscous secretion that shows distinct structural characteristics along the length of the intestinal tract, reflecting the physiological requirements and the microbial load in the respective intestinal compartments (Figure 1). The oral cavity is covered by a relatively thin (up to 100 µm) salivary film, whereas the stomach mucus layer needs to protect the underlying epithelium from acidic conditions and measures approximately 300 µm in thickness [1][3][7,9]. In the small intestine, a relatively thin (100–500 µm), loose, and unattached mucus layer allows for efficient nutrient absorption [1][4][7,10]. The colon presents the organ with the thickest mucus layer, measuring around 830 µm, and, in contrast to the small intestine, is composed of an inner stratified layer that is mostly sterile and an outer loose layer that forms a habitat for bacteria [1][5][7,11]. This organization is critical for gastrointestinal tract homeostasis, separating most of the luminal microorganisms from the epithelium and the immune system.

Mucus is composed of approximately 95% water, highly glycosylated mucin glycoproteins, lipids, electrolytes, bile salts, antimicrobial enzymes, and immunoglobulins. Mucin proteins form the major building blocks of mucus and are composed of a mucin protein core domain rich in amino acids that form attachments sites for N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), which in turn forms extended glycan epitope structures [6][7][12,13]. Further to their core domain, mucins can have transmembrane domains that allow cell membrane anchorage [8][14]. This classifies mucins into cell surface mucins or secreted gel-forming mucins. To date, 21 different mucins have been identified, of which the MUC2-secreted gel-forming mucin represents the major intestinal mucin. Goblet cells of the intestinal epithelium constitutively produce and secrete mucus (Figure 1). In the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of goblet cells, MUC2 monomers dimerize and subsequently trimerize via C-terminal and N-terminal disulfide bridges, respectively [9][10][15,16]. These densely packed oligomers are secreted in response to a decrease in Ca2+ concentration and increased pH, and subsequently become highly hydrated to form greatly expanded organized sheets that comprise the three-dimensional mucus layer [11][17]. MUC2 is a highly O-glycosylated mucin, with more than 80% of its total molecular weight (2.7 MDa) consisting of oligosaccharide side chains that form a crucial part of microbe–mucus interactions [12][13][18,19] discussed in more detail in Section 3. Mucin glycans are mainly composed of O-glycosylated (and to a lesser extent N-glycosylated) protein cores with glycosyl chains of 2–12 monosaccharides consisting of galactose, fucose, N-acetylgalactosamine, N-acetylglucosamine, mannose, and sialic acid [14][20]. Studies in humans and rodents characterizing mucin glycosylation show regiospecificity along the gastrointestinal tract that is relatively conserved between individuals [15][21].

Figure 1. Simplified graphical illustration of mucus thickness and synthesis. Mucus thickness and bacterial load increase from the proximal to the distal end of the gastrointestinal tract. Shown in the left panel are mucus thickness values for the stomach, small intestine, and colon. While the stomach and colon have clearly defined inner and outer mucus layers, the small intestine does not. Shown in the middle panel is a cross-section of a wild-type mouse colon after fluorescent in situ hybridization using a bacterial EUB388 probe (red) and anti-MUC2 staining (green). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Bacteria are clearly confined to the outer mucus layer, with the stratified inner layer being devoid of bacteria. The right panel represents a simplified depiction of MUC2 synthesis in the corresponding goblet cell compartments (ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Golgi, Golgi apparatus; SG, secretory granules).

1.2. Mucus Layer Function

As the first line of defense protecting the intestinal epithelium, mucus contributes to the maintenance of epithelial homeostasis and protects against mechanical, chemical, and biological assaults. As a physical barrier, it separates external substances, enzymes, and bacteria from the epithelium. It was recently suggested that intestinal mucus forms three lines of defense against bacteria [16][22]. Firstly, through the physical inner mucus layer barrier, secondly, via the sentinel goblet cell response, and thirdly, through the crypt goblet cell-emptying response. Particularly in the colon, the inner mucus layer forms a size-exclusion filter that separates the intestinal microbiota from the host [5][11]. Consequently, intestinal bacteria are kept at a distance from the epithelium due to IgA-induced bacterial aggregates that are too large to diffuse through the colonic mucus layer [17][23]. In case the first mucus defense barrier is breached, specialized sentinel goblet cells that are situated along the top of intestinal crypts respond by secreting a mucus plume to wash away penetrating bacteria [18][24]. Following this response, crypt goblet cell emptying is the last attempt to protect the epithelium from the invading bacteria [19][25]. At the same time as forming a physical hurdle, the mucus layer simultaneously acts as a diffusion barrier that allows ions, nutrients, and water to reach the enterocytes and provides nutrients and attachment sites for the intestinal microbiota [20][21][26,27]. This relationship between the microbiota and mucus is very intricate. A recent publication by Bergstrom et al. has added another functional aspect to mucus, demonstrating that proximally derived O-glycosylated mucus encapsulates fecal material and the microbiota to modulate microbiota structure and function, as well as transcription in the colon mucosa [22][28]. Interestingly, the microbiota directs its own encapsulation by inducing Muc2 production from proximal colon goblet cells [22][28]. This work has also introduced a major revision to the current mucus system model of locally produced mucus through the identification of two distinct O-glycosylated entities of MUC2: a major form produced by the proximal colon that encapsulates and shapes the microbiota and a minor form derived from the distal colon that adheres to the major form [22][28]. Its high water content renders the mucus layer as a lubricant that protects against dehydration and mechanical stress [23][29]. Importantly, intestinal mucus also forms the first line of immunological defense limiting exposure to antigens and bacteria and through direct interaction between mucin glycans and immune cells via lectin-like proteins [20][24][26,30]. MUC2 was found to imprint dendritic cell tolerance, implying an important role of glycosylated mucin domains in tolerogenic mechanisms [25][31].

2. The Mucin Glycocode: Facilitator of Microbe–Mucus Interactions

The plethora of variations in the precise interplay of glycosyltransferases involved in O-glycan synthesis allows for an enormous structural variability in mucin glycans, which present a form of glycocode [26][32], which may serve as an interspecies communication facilitator between microbes and the host. These mucin glycans represent potential attachments sites and an energy source to intestinal microbes, thereby acting as a facilitator of microbe–mucus interactions. By providing attachment sites and a source of nutrients through the intestinal mucus, the host likely selects its commensal microbiota, rendering intestinal mucus as one of numerous factors (as, for example, antimicrobial peptides and dietary factors) that control species- and site-specific microbial composition at the epithelial interface. In a symbiotic state of homeostasis, this preserves health, while in a dysbiotic milieu, it seems feasible that opportunistic bacteria or pathogens may alter host mucus in such a way that it forces the host to “select” a different microbial community that potentially drives disease pathology.

2.1. Mucin Glycans as a Bacterial Attachment Site

The ability to attach to the host is a prerequisite for colonization and prolonged gastrointestinal residency of microbes [27][33]. Adhesion of commensal bacteria to intestinal mucus benefits the host as it is suggested to be one of the mechanisms for host colonization resistance of pathogens, achieved by competing for attachment sites, producing antimicrobials, modulation of immune responses, reducing oxygen levels, and depleting nutrients [28][34]. Microbes express adhesins that enable attachment to mucus, including extracellular appendages, such as pili and flagella, as well as specific mucus-binding proteins (MUBs) (reviewed in [29][35]). The gram-positive bacterium and well-established probiotic strain, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG was shown to express mucus-binding pili on its surface, with pilin subunits shown to either directly bind to mucin domains or bind through electrostatic contacts [30][36]. Flagella have also been reported to display adhesive properties to mucus in both pathogenic and probiotic strains [31][32][37,38]. In another example, Bifidobacterium infantis was shown to harbor oligosaccharide-binding proteins, which facilitate the bacterial mucus-binding ability [33][39]. In gnotobiotic mice colonized with Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli, B. fragilis were found in the mucus layer, while E. coli were restricted to the lumen [34][40]. Further analysis showed that B. fragilis specifically binds to highly purified mucins, suggesting mucus binding as a likely mechanism for intestinal colonization [40]. MUBs are extracellular adhesion effector molecules of lactobacilli [35][41], with the best-studied example being the 353-kDa MUC produced by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 53,608 that interacts with specific muco-oligosaccharides [36][37][42,43]. Their molecular nature and precise function in vivo remain to be elucidated.

2.2. Mucin Glycans as a Bacterial Energy Source

The permanently renewing intestinal mucus layer represents an important ecological niche rich in nutrients, providing a particularly beneficial environment to commensal bacteria. The use of host-derived mucin glycans as an energy source becomes particularly important when dietary glycans are sparse. A clear growth advantage in such scenarios is evident for metabolically flexible commensal bacteria that are able to sequentially degrade mucin O-glycans for utilization as carbon and energy sources. This degradation is governed by the specific enzymes produced by the commensal bacteria or pathogens, including esterases, glycosidases, sulfatases, and specific mucinases that cleave the protein backbone [38][39][44,45]. Bacteria recognize compact mucin glycan structures and degrade the individual glycans to yield short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that diffuse through the inner mucus layer and present an energy source for the intestinal epithelial cells. The harvest of degraded glycans for their own metabolism presents a colonization advantage for bacteria. At the same time, this glycan degradation makes oligosaccharides available to non-mucin degrading bacteria as part of a microbial food chain, therefore maintaining the intestinal microbiota as a whole. Mucin degradation was initially associated with pathogenicity [40][41][46,47]. Since then, it has become apparent that a large portion of the genome of certain commensal bacteria, including Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Barnesiella intestinihominis, Ruminococcus gnavus, and Akkermansia muciniphila, is dedicated to complex carbohydrate degradation and utilization [42][43][48–51]. Martens et al. identified that B. thetaiotaomicron contains polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs) that are upregulated when grown on O-glycans and showed that B. thetaiotaomicron mutants for O-glycan PULs are outcompeted by wild-type strains in mice fed a simple sugar diet [44][52]. These findings demonstrate B. thetaiotaomicron requires glycans, including mucins, for successful colonization. Ironically, while the B. thetaiotaomicron sialidase harvests sialic acid from mucin glycans, the bacterium is unable to utilize sialic acid, making it available to and promoting the growth of other bacteria, including the enteric pathogens Clostridium difficile and Salmonella typhimurium [45][53]. Another well-known mucin-degrading specialist is A. muciniphila, an abundant resident of the human gut [46][47][54,55]. An in vitro study investigating A. muciniphila’s colonization preferences and response to environmental parameters, such as pH and mucins, showed that mucins as a nutritional source are a more important modulator of the microbiota composition than pH [48][56]. Authors observed higher levels of Akkermansia, Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, Sutterella, and Arthrobacter in a cluster of mucin-rich bacterial communities that was significantly different from that of mucin-deprived communities [48][56]. It is well-accepted that host factors (including mucus and antimicrobial peptides), diet, age, and the mode of birth represent examples of factors that shape the composition of the intestinal microbiota and its modulation [49][57]. For example, a systematic review of clinical trials concluded that an increase in abundance of A. muciniphila was observed following dietary modulation through caloric restriction, supplementation with pomegranate extract, resveratrol, polydextrose, or sodium butyrate [50][58], rendering diet as one important modulator of this mucin-degrading specialist. A. muciniphila has been shown to possess probiotic properties, prevent or treat metabolic disorders, reduce metabolic inflammation, and restore the gut barrier [51][52][53][59–61], contributing to the maintenance of mucosal integrity. A study maintaining mice on a polysaccharide-deficient diet demonstrated that the mucin-degrading generalist B. thetaiotaomicron turns to host mucus glycan foraging when polysaccharides are absent [54][49]. In line with this, Desai et al. were able to show that a diet deficient in complex plant fiber promotes expansion and activity of the mucin-degrading bacteria A. muciniphila and Bacteroides caccae in a synthetic human gut microbiota assembled in a gnotobiotic mouse model [55][62]. This shift in mucin-degrading bacteria was shown to alter the status of the colonic mucus barrier and susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium–induced colitis [55][62]. Findings support a model of triangular interplay between dietary fiber, intestinal microbiota metabolism, and intestinal mucus, which may impair the intestinal mucus barrier and increase susceptibility to pathogens. The presence and activity of mucin-degrading bacteria in the mucus layer may have strong positive and negative effects on host health, highlighting the need to understand the role of mucins in microbial community dynamics and microbe–host interactions.

3. The Microbiota as a Modulator of Intestinal Mucus

The interaction of microbes and intestinal mucus is bidirectional, where not only mucus and mucin glycans select the microbiota composition, but where the intestinal microbiota shapes mucus properties. Evidence of a direct effect of the intestinal microbiota on mucus layer properties was demonstrated by the requirement of meprin β, a protease activated upon bacterial exposure, for small intestinal mucus release [56][63]. Furthermore, the modulation of the mucin glycan profile in the presence of bacteria has also been observed (reviewed in [43][51]). The density of the intestinal microbiota forms a gradient along the length of the intestinal tract, reaching its highest load of 1011 bacteria/mL content in the colon [57][1]. The observation that both the intestinal mucus thickness and the microbial load increase towards the distal end of the intestinal tract [[57][1]1,7] provides evidence for a clear association between the two. In line with this, mucus is thinner and penetrable to microbiota-sized beads in germ-free animals, and its secretion can be stimulated through exposure to such bacterial products as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and peptidoglycans (PGN) [58][64]. Conserved microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) can be recognized by intestinal epithelial cells through a family of innate immune system receptors called toll-like receptors (TLRs), most of which signal by recruiting the key adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) to initiate signaling cascades involved in inflammatory and tissue renewal and repair responses [59][65].The importance of TLR family members in influencing mucus properties was demonstrated in intestinal epithelial-specific myeloid differentiation primary response 88 knockout mice (IEC-Myd88−/−), which showed decreased mucus production [60][66]. A deficiency of MyD88 has been shown to cause increased susceptibility to chemically induced colitis and infectious colitis, with IEC-Myd88-/- mice displaying exaggerated tissue damage, reduced antimicrobial responses, and impaired goblet cell responses [60][61][62][66–68]. Furthermore, MyD88 deficiency in the ApcMin/+ mouse model of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis demonstrated that MyD88 signaling substantially contributes to tumor growth [63][69]. A further example demonstrating the importance of receptor signaling on intestinal mucus properties is provided by vitamin D/vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling. Vitamin D/VDR signaling has increasingly been recognized to play a role in intestinal homeostasis to modulate the intestinal barrier, the microbiota, and immune responses [64][70]. Evidence suggests a beneficial role of vitamin D/VDR signaling in experimental and clinical IBD, attributed to alterations in the microbiota [65][66][67][71–73]. Amongst other functions, vitamin D/VDR signaling regulates antimicrobial peptide levels in intestinal mucus [68][69][74,75]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated a role for vitamin D/vitamin D receptor signaling in modulating mucus secretion through the regulation of Ca2+ assimilation [66][70][72,76]. Evidently, vitamin D/VDR signaling, the intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal mucus layer are connected through a complex interplay to maintain epithelial homeostasis. A study investigating the modulation of intestinal mucus by commensal bacteria demonstrated that a period of six weeks is required for the colonic inner mucus layer to become impenetrable to bacteria following the colonization of germ-free mice [71][77]. Furthermore, this study showed that an additional two weeks (eight weeks in total) of colonization are required to reach a bacterial composition of conventionally raised mice. Together, these findings demonstrate the complex dynamics of mucus layer development and conventionalization in germ-free mice, indicating that studies investigating mature microbe–mucus interactions and characteristics of the latter should therefore be performed after a minimum eight-week colonization period. The comparison between two genetically identical mouse colonies housed in separate rooms of the same specific pathogen-free animal facility revealed that the microbiota composition differed between the two locations and affected inner mucus layer penetrability [72][78]. The transfer of cecal microbiota from these mice to germ-free mice transmitted the microbiota-induced mucus phenotype [72][78]. These findings demonstrate that the microbiota and its community structure directly affect mucus barrier properties, with potential implications for disease. A dysfunctional mucus layer may allow bacteria to come into direct contact with the epithelium, triggering adverse host responses, such as an inflammatory response, and allowing bacteria that are uncharacteristic for this milieu to find a niche and flourish. What remains to be fully understood is the exact mechanism by which bacteria trigger mucus development and mucus release and which members of the intestinal microbiota form key players in this process.