Silk fibroin protein materials have shown excellent tensile strength, flexibility and biocompatibility. Natural silk fibers are composed of sericin coating and silk fibroin proteins. Sericin as a protective gel coat wraps the silk fibroin, which can be removed by a degumming process. Silk fibroin protein contains 18 amino acids, of which simple glycine (Gly), alanine (Ala) and serine (Ser) account for above 70%.

- silk fibroin protein

- composite material

- magnetic nanoparticles

- secondary structure

- film

1. Introduction

Magnetic nanoparticles have been widely used in the biomedical fields such as targeted drug delivery, biosensors, cancer treatment and medical imaging, due to their small size, tunable surface chemistry and controllable magnetization. Their magnetic properties mainly depend on the size, shape and particle distribution, which may be significantly different from those of their bulk counterparts. Magnetic particles can be easily functionalized with other biopolymer materials such as proteins to improve their mechanical flexibility and biocompatibility. BaFe

12

O

19 is a hexagonal magnetoplumbite-type ferrite material [1,2], which has a remarkably high intrinsic coercivity, saturation magnetization and Curie temperature [3]. These unusual properties give it great potential for use in biological science applications. Cobalt is another broadly used magnetic material, which has stable chemical properties at room temperature, with a Curie temperature of up to 1121 °C [4]. Fe

is a hexagonal magnetoplumbite-type ferrite material [1][2], which has a remarkably high intrinsic coercivity, saturation magnetization and Curie temperature [3]. These unusual properties give it great potential for use in biological science applications. Cobalt is another broadly used magnetic material, which has stable chemical properties at room temperature, with a Curie temperature of up to 1121 °C [4]. Fe

3

O

4 has been used in the biomedicine field recently, specifically with applications on magnetic resonance imaging, targeted drug delivery and tumor hyperthermia [5,6,7,8,9]. Magnetic Fe

has been used in the biomedicine field recently, specifically with applications on magnetic resonance imaging, targeted drug delivery and tumor hyperthermia [5][6][7][8][9]. Magnetic Fe

3

O

4 nanoparticles have high biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity [6,8], while their production method is simple and low-cost. Due to the existence of various free radical groups in human body fluids, the direct use of magnetic particles in the body can be largely limited and even cause harm to the human body. Therefore, a functional composite material that combines magnetic particles and biocompatible protein materials can significantly enhance the advantages of the two components and expand their scope of application.

nanoparticles have high biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity [6][8], while their production method is simple and low-cost. Due to the existence of various free radical groups in human body fluids, the direct use of magnetic particles in the body can be largely limited and even cause harm to the human body. Therefore, a functional composite material that combines magnetic particles and biocompatible protein materials can significantly enhance the advantages of the two components and expand their scope of application.

Silk fibroin protein materials have shown excellent tensile strength, flexibility and biocompatibility [10,11,12]. Natural silk fibers are composed of sericin coating and silk fibroin proteins. Sericin as a protective gel coat wraps the silk fibroin, which can be removed by a degumming process [13]. Silk fibroin protein contains 18 amino acids, of which simple glycine (Gly), alanine (Ala) and serine (Ser) account for above 70% [14,15]. The secondary structure of silk fibroin includes β-sheets, random coils and α-helices [16,17,18], which greatly control the physical properties. For instance, the mechanical properties of silk fiber can be enhanced by a high content of β-sheet crystals [19,20]. The highly crosslinked silk fibril network structure through β-sheet crystals is believed to also cause the insolubility of the regenerated silk materials in water and many mild organic solvents [10,21]. Different forms of silk materials, such as films, gels, particles and fibers, have shown great potential in biomedical applications [22,23,24,25], and by manipulating their secondary structure, one can control the release time and dose during targeted drug delivery [18,26]. A high content of β-sheet crystals, which can be stimulated through alcohol solutions or water annealing, also helps to improve cell adhesion and tissue growth [25,27,28]. In addition, the hydrophilic functional groups on the network composed of the protein chain and its crosslinked structure can make the material absorb water while still maintaining its shape and structure well, permitting its use for bone reconstruction, bioelectronics, and

Silk fibroin protein materials have shown excellent tensile strength, flexibility and biocompatibility [10][11][12]. Natural silk fibers are composed of sericin coating and silk fibroin proteins. Sericin as a protective gel coat wraps the silk fibroin, which can be removed by a degumming process [13]. Silk fibroin protein contains 18 amino acids, of which simple glycine (Gly), alanine (Ala) and serine (Ser) account for above 70% [14][15]. The secondary structure of silk fibroin includes β-sheets, random coils and α-helices [16][17][18], which greatly control the physical properties. For instance, the mechanical properties of silk fiber can be enhanced by a high content of β-sheet crystals [19][20]. The highly crosslinked silk fibril network structure through β-sheet crystals is believed to also cause the insolubility of the regenerated silk materials in water and many mild organic solvents [10][21]. Different forms of silk materials, such as films, gels, particles and fibers, have shown great potential in biomedical applications [22][23][24][25], and by manipulating their secondary structure, one can control the release time and dose during targeted drug delivery [18][26]. A high content of β-sheet crystals, which can be stimulated through alcohol solutions or water annealing, also helps to improve cell adhesion and tissue growth [25][27][28]. In addition, the hydrophilic functional groups on the network composed of the protein chain and its crosslinked structure can make the material absorb water while still maintaining its shape and structure well, permitting its use for bone reconstruction, bioelectronics, and

in vivo tumor models [29,30,31].

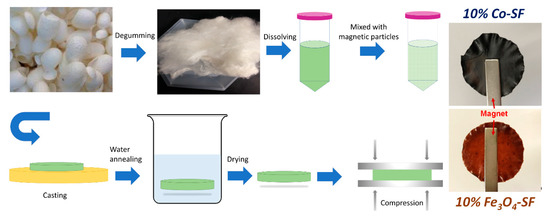

In this study, three magnetic nanoparticles, M-type hexaferrite BaFe

12

O

19

(BaM), Fe

3

O

4

, and cobalt (Co) particles were blended with silk fibroin (SF) proteins to form robust composite films (denoted as BaM-SF, Fe

3

O

4

-SF and Co-SF, respectively) by a wet-pressing method (

). Performance of the obtained silk-magnetic functional films were comparatively evaluated at various concentrations of different magnetic particles. The effect of particle concentration on the secondary structure of silk fibroins was studied by FTIR analysis. TGA and DSC were used to study the thermal stability and transitions of silk-magnetic composite films, and SEM with EDS was used to characterize the morphology of the silk films and the distribution of the particles while the magnetization was studied by magnetometry. This comparative study helps us better understand the interactions between the organic matrix and the inorganic inclusions in composites, which have a variety of potential uses as sustainable or biomedical materials.

Figure 1.

Procedures to prepare magnetic silk fibroin composite films.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Analysis

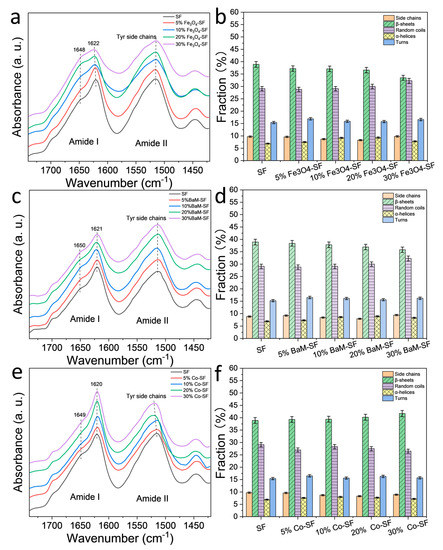

FTIR is an effective tool to characterize the secondary structure and functional group of silk protein materials [16,17] (

FTIR is an effective tool to characterize the secondary structure and functional group of silk protein materials [16][17] (

). For Fe

3

O

4

-SF samples, there is a sharp peak at 1622 cm

−1

, suggesting the β-sheet crystal structures are dominant. However, the peak shoulder at 1646 cm

−1

(random coils structures) increased with Fe

3

O

4

content, indicating that relative fraction of β-sheet crystals decreased. All BaM-SF samples also showed a sharp peak at 1620 cm

−1

, indicating a predominant β-sheet secondary structure due to the wet-pressing method. The peak at 1650 cm

−1

slightly increased when more nanoparticles were present, suggesting that the BaM particles in the silk matrix can also slightly enhance the formation of α-helix or random coils structures. However, this structural change is not as significant for the Fe

3

O

4

-SF samples. Compared to the FTIR patterns of BaM-SF and Fe

3

O

4

-SF, Co-SF samples showed much sharper peaks at 1622 cm

−1

, suggesting it has the highest β-sheet crystal content among the three types of magnetic inclusions. In addition, the shoulder at 1651 cm

−1

decreased with the increase in Co particle content. In the amide II region, all three types of composite films showed peaks around 1515 cm

−1

, which suggests Tyr side chains structure.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of (

a

) Fe

3

O

4

-silk fibroin (SF), (

c

) BaM-SF and (

e

) Co-SF composite films. Secondary structure contents of (

b

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

d

) BaM-SF and (

f

) Co-SF calculated from a Fourier self-deconvolution curve fitting method.

A quantitative analysis of the secondary structure contents was performed with a Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD) curve fitting method (

b,d,f) [16]. It shows that β-sheet content of SF sample is around 39% composed of mainly inter-molecular β-sheets [10]. The β-sheet content of the Fe

3

O

4

-SF samples decreases with Fe

3

O

4

content, reaching 33% at 30 wt%, while the random coils content increased slightly by 29–32%. Similar behavior was found in BaM-SF samples, where the β-sheet content decreased with an increase in BaM weight fraction, while the random coils content nominally increased. In contrast, for the Co-SF samples, the secondary structure remained almost unchanged with a slight increase in β-sheet content.

2.2. Morphology Analysis

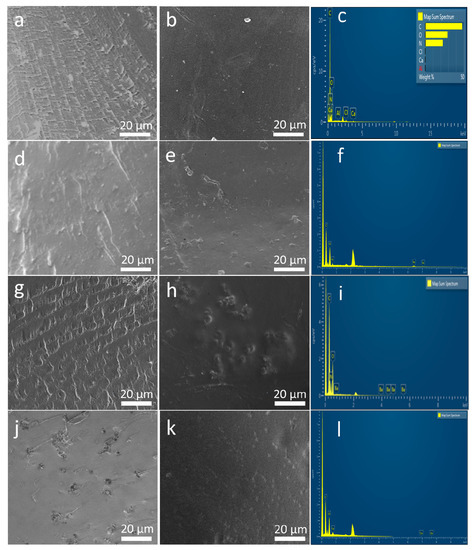

Surface and cross-section morphology of SF and magnetic silk composite films are shown in

. Lamellar patterns evenly spread out across the cross section of SF and 20% BaM-SF films (

a,g). Cross section of 20% Fe

3

O

4

(

d) showed a rougher morphology with wrinkles and densely distributed particles. Cross section of 20% Co-SF (

j) showed evenly distributed holes with connected wrinkles. When comparing the surface samples to the cross-sectional, the surface seems to be much more homogenous, containing fewer aggregates and wrinkles. SF film shows a smooth and uniform surface (

b). A 20% BaM-SF sample (

h) showed a relatively rough surface, and BaM particles distribute homogenously instead of forming big aggregates. Compared to the surface morphology of 20% BaM-SF film, 20% Fe

3

O

4

(

e) and 20% Co-SF (

k) films showed smooth and uniform surface morphology with shallow pits. EDS spectra and analyses of the SF, 20% Fe

3

O

4

-SF, 20% BaM-SF and 20% Co-SF films are shown in

c,f,i,l, respectively. As mentioned above, most CaCl

2

residue has been washed out of the pure SF film after the water annealing process (

c). The EDS spectra of various elements in the composites also showed evidence of Fe (6.403 keV and 0.705 keV,

f), Ba (4.465 keV and 0.779 keV,

i) and Co (6.929 keV and 0.776 keV,

l) elements in their respective composite films.

Figure 3.

(

a

,

d

,

g

,

j

) The cross section of SF film, 20% Fe

3

O

4

-SF, 20% BaM-SF and 20% Co-SF composite, respectively; (

b

,

e

,

h

,

k

) are the surface morphology of SF film, 20% Fe

3

O

4

-SF, 20% BaM-SF and 20% Co-SF composite, respectively; (

c

,

f

,

i

,

l

) display the EDS spectra for the SF, 20% Fe

3

O

4

-SF, 20% BaM-SF and 20% Co-SF films, respectively.

2.3. Thermal Analysis

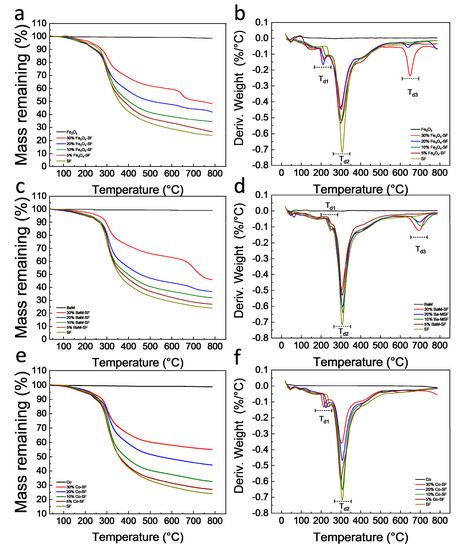

Thermal stability of the silk magnetic composite films was characterized by TGA (

,

). All three types of magnetic particles are thermally stable with no degradation for all of them up to 800 °C. All Fe

3

O

4

-SF composite films showed a small degradation in the range of 209~226 °C (T

d1

), a major degradation between 296 and 303 °C (T

d2

) and a third degradation around 650 °C (T

d3

). The residual weight of Fe

3

O

4

-SF samples at 800 °C was between 26.6 and 48.2%, which generally increased with Fe

3

O

4

content. All BaM-SF composite films showed a small degradation between 238 and 251 °C (T

d1

) and a major degradation between 301 and 309 °C (T

d2

). When the BaM concentration was 10% or above, a third degradation (T

d3

) was found around 700 °C (

c,d). The residual weight of BaM-SF samples at 800 °C was between 27.1 and 46.1%, and the residual weight increased with BaM content. All Co-SF composite films showed a small degradation at 214~233 °C (T

d1

) and a major degradation at 300~307 °C (T

d2

). The residual weight of Co-SF samples at 800 °C is between 27.1 and 55.1%, and increased with Co content. However, no third degradation peak (T

d3) was observed around 600~700 °C for any of Co-SF samples. The first small degradation is mainly from the unstable part of silk proteins [32,33,34]. BaM-SF samples showed a higher T

) was observed around 600~700 °C for any of Co-SF samples. The first small degradation is mainly from the unstable part of silk proteins [32][33][34]. BaM-SF samples showed a higher T

d1

than that of the other two types of composites, suggesting that BaM particles were able to best protect silk materials. The third degradation for Fe

3

O

4

-SF and BaM-SF samples is probably from a stable phase that formed when the Fe combined with the silk protein.

Figure 4.

Thermogravimetric curves of (

a

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

c

) BaM-SF and (

e

) Co-SF composite films. The 1st derivative TG (DTG) curves of (

b

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

d

) BaM-SF and (

f

) Co-SF composite films.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of Fe

3

O

4

-SF, BaM-SF and Co-SF composite films *.

| Tw (°C) | Td1 (°C) | Td2 (°C) | Td3 (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF | 48 | 245 | 308 | - |

| 5% Fe3O4-SF | 49 | 219 | 303 | 657 |

| 10% Fe3O4-SF | 52 | 226 | 297 | 659 |

| 20% Fe3O4-SF | 46 | 209 | 296 | 641 |

| 30% Fe3O4-SF | 50 | 215 | 303 | 650 |

| 5% BaM-SF | 63 | 250 | 308 | - |

| 10% BaM-SF | 64 | 251 | 309 | 708 |

| 20% BaM-SF | 60 | 250 | 306 | 697 |

| 30% BaM-SF | 61 | 238 | 301 | 696 |

| 5% Co-SF | 52 | 233 | 300 | - |

| 10% Co-SF | 54 | 234 | 307 | - |

| 20% Co-SF | 50 | 223 | 307 | - |

| 30% Co-SF | 52 | 214 | 303 | - |

* Data was obtained from TGA. The weight derivative peak position was used as the degradation temperature. All temperature values have an error bar within ± 0.5 °C.

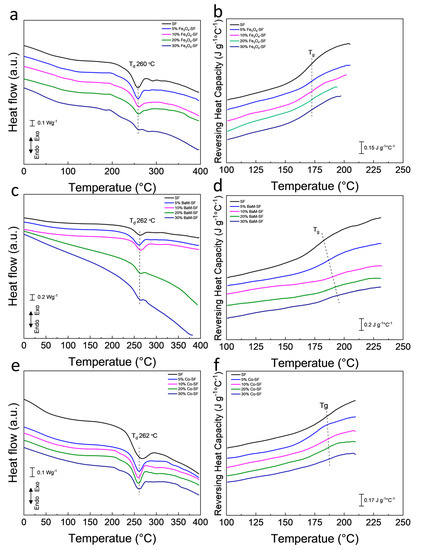

Heat flow and reversing heat capacity of magnetic silk composite films measured from DSC are shown in

. Heat flow analysis shows that all three type composite films have a major degradation about 260 °C, which is from the decomposition of silk proteins. The amorphous part of the polymer has a greater mobility with increasing temperature, which is defined as the glass transition. The glass transition is gradual and reversible, and the heat capacity of the polymer changes dramatically during this transition [35]. All Fe

3

O

4

-SF samples showed a similar glass transition temperature around 172 °C. The glass transition temperature of BaM-SF composite films increased from 172 °C for SF, to 192 °C for 30% BaM-SF, suggesting that the mobility of the amorphous structure in BaM-SF composites can be tuned by the BaM particles. All Co-SF composite films showed a glass transition temperature around 180 °C.

Figure 5.

Heat flow of (

a

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

c

) BaM-SF and (

e

) Co-SF composite films. Reversing heat capacity of (

b

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

d

) BaM-SF and (

f

) Co-SF.

2.4. Magnetization Analysis

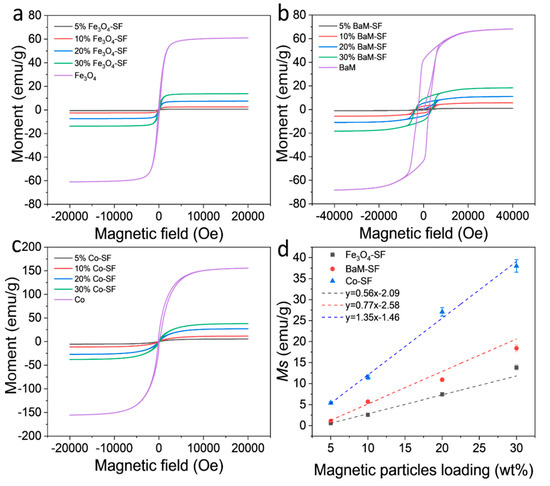

Magnetization of the three types of composite films showed typical ferromagnetic behavior with coercive field of about 128 Oe (Fe

3

O

4

), 3660 Oe (BaM) and 165 Oe (Co), respectively (

a–c). The dependence of the magnetization on weight fraction of magnetic particles are shown in

d. The saturation magnetization

Ms

of Fe

3

O

4

, BaM and Co nanoparticles is about 61 emu/g, 68 emu/g and 156 emu/g, respectively. Since silk protein matrix has magnetic susceptibility near zero, it can be assumed that the moment of the composite films depends only on the net weight of the magnetic particles. Therefore, one would anticipate that the

Ms

value of the composite should be about

xMs

, where

x

is the weight fraction of magnetic particles. All samples display a linear dependence of

Ms

on weight fraction; however, note that neither line intercepts the origin. Presumably, all three types of magnetic particles partially dissolved in the formic acid solution, saturating the solution at about 3.7 wt%, 3.4 wt% and 1.1 wt% (horizontal intercept of the graph) for Fe

3

O

4

, BaM and Co particles, respectively. These results are consistent with the study of the secondary structure of SF matrix. In any case, at sufficient loading, of three types of composite films maintain a sizable magnetization for potential use in MRI imaging or targeted drug delivery.

Figure 6.

Magnetization and hysteresis loops of (

a

) Fe

3

O

4

-SF, (

b

) BaM-SF and (

c

) Co-SF composite films at room temperature. (

d

) Saturation moment of Fe

3

O

4

-SF, BaM-SF and Co-SF composite films as a function of the magnetic particle content.

2.5. Self-Assembly Mechanism

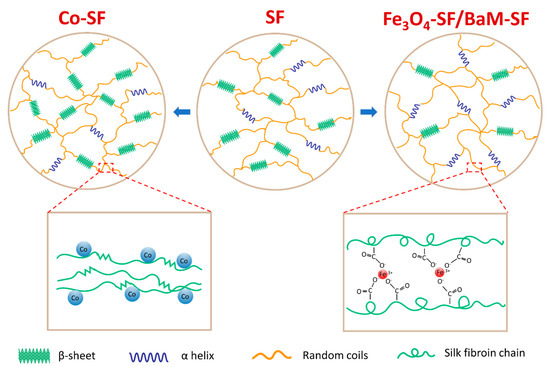

With the experimental evidence and analysis provided above, we can confirm that Fe

3

O

4

and BaM particles can slightly prevent the β-sheet crystal formation, suggesting that the Fe

3

O

4

-SF and BaM-SF composite films have more noncrystalline structures (

). This is probably caused by the strong coordination bonding between Fe

3+ ions and carboxylate ions on silk fibroin chains [36,37,38] due to the dissolved Fe found from the magnetization studies. Most β-sheet crystals usually formed during the water annealing and wet pressing process. However, when the Fe

ions and carboxylate ions on silk fibroin chains [36][37][38] due to the dissolved Fe found from the magnetization studies. Most β-sheet crystals usually formed during the water annealing and wet pressing process. However, when the Fe

3

O

4

and BaM particles were present, the strong coordination bonding limited the mobility of silk fibroin chain and further prohibited the β-sheet crystal formation (

). The unique high temperature degradation (T

d3

) of Fe

3

O

4

-SF and BaM-SF samples found in TG analysis may be another indicator of this stable phase, which is formed when Fe is combined with silk protein. On the other hand, the amount of dissolved Co is minimal as compared to that of the Fe, so the addition of Co nanoparticles has less effect on the secondary structure. Since a large amount of Co particles will occupy more space in the Co-SF film, the silk protein chains are able to be closer to each other, resulting in a slight increase in β-sheet crystals (

).

Figure 7. The effect of iron-based (Fe3O4 or BaM) and cobalt-based (Co) magnetic particles on the secondary structures of silk fibroin material.

References

- Fuchikami, N. Magnetic anisotropy of magnetoplumbite BaFe12O19. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1965, 20, 760–769.

- Anbarasu, V.; Gazzali, P.M.; Karthik, T.; Manigandan, A.; Sivakumar, K. Effect of divalent cation substitution in the magnetoplumbite structured BaFe12O19 system. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013, 24, 916–926.

- Xu, P.; Han, X.; Zhao, H.; Liang, Z.; Wang, J. Effect of stoichiometry on the phase formation and magnetic properties of BaFe12O19 nanoparticles by reverse micelle technique. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 1305–1308.

- Atwater, J.; Akse, J.; Jovanovic, G.; Sornchamni, T. Preparation of metallic cobalt and cobalt-barium titanate spheres as high temperature media for magnetically stabilized fluidized bed reactors. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2001, 20, 487–488.

- Lai, C.W.; Wang, Y.H.; Lai, C.H.; Yang, M.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Chou, P.T.; Chan, C.S.; Chi, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsiao, J.K. Iridium-complex-functionalized Fe3O4/SiO2 core/shell nanoparticles: A facile three-in-one system in magnetic resonance imaging, luminescence imaging, and photodynamic therapy. Small 2008, 4, 218–224.

- Xuan, S.; Wang, F.; Lai, J.M.; Sham, K.W.; Wang, Y.-X.J.; Lee, S.-F.; Yu, J.C.; Cheng, C.H.; Leung, K.C.-F. Synthesis of biocompatible, mesoporous Fe3O4 nano/microspheres with large surface area for magnetic resonance imaging and therapeutic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 237–244.

- Shen, J.-M.; Tang, W.-J.; Zhang, X.-L.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.-X. A novel carboxymethyl chitosan-based folate/Fe3O4/CdTe nanoparticle for targeted drug delivery and cell imaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 239–249.

- Xu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, W.; Xu, J.; Zuo, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, N. Magnetic hyperthermia ablation of tumors using injectable Fe3O4/calcium phosphate cement. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 13866–13875.

- Luo, K.-y.; Shao, Z.-z. A novel regenerated silk fibroin-based hydrogels with magnetic and catalytic activities. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 35, 515–523.

- Xue, Y.; Wang, F.; Torculas, M.; Lofland, S.; Hu, X. Formic acid regenerated mori, tussah, eri, thai, and muga silk materials: Mechanism of self-assembly. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 6361–6373.

- Hu, X.; Kaplan, D.; Cebe, P. Dynamic protein−water relationships during β-sheet formation. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3939–3948.

- Hu, X.; Cebe, P.; Weiss, A.S.; Omenetto, F.; Kaplan, D.L. Protein-based composite materials. Mater. Today 2012, 15, 208–215.

- Lamoolphak, W.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Shotipruk, A. Hydrothermal production and characterization of protein and amino acids from silk waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7678–7685.

- Kawakami, M.; Shimura, K. Fractionation of glycine, alanine, and serine transfer ribonucleic acids from the silk gland. J. Biochem. 1973, 74, 33–40.

- Vepari, C.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk as a biomaterial. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 991–1007.

- Hu, X.; Kaplan, D.; Cebe, P. Determining beta-sheet crystallinity in fibrous proteins by thermal analysis and infrared spectroscopy. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 6161–6170.

- McGill, M.; Holland, G.P.; Kaplan, D.L. Experimental methods for characterizing the secondary structure and thermal properties of silk proteins. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, 1800390.

- Choi, M.; Choi, D.; Hong, J. Multilayered controlled drug release silk fibroin nanofilm by manipulating secondary structure. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 3096–3103.

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tan, X.; Xie, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q. A strategy for improving the mechanical properties of silk fiber by directly injection of ferric ions into silkworm. Mater. Des. 2018, 146, 134–141.

- Guo, Z.; Xie, W.; Gao, Q.; Wang, D.; Gao, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, L. In situ biomineralization by silkworm feeding with ion precursors for the improved mechanical properties of silk fiber. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 21–26.

- Cebe, P.; Partlow, B.P.; Kaplan, D.L.; Wurm, A.; Zhuravlev, E.; Schick, C. Silk I and Silk II studied by fast scanning calorimetry. Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 323–332.

- Love, S.A.; Popov, E.; Rybacki, K.; Hu, X.; Salas-de la Cruz, D. Facile treatment to fine-tune cellulose crystals in cellulose-silk biocomposites through hydrogen peroxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 569–575.

- Crivelli, B.; Perteghella, S.; Bari, E.; Sorrenti, M.; Tripodo, G.; Chlapanidas, T.; Torre, M.L. Silk nanoparticles: From inert supports to bioactive natural carriers for drug delivery. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 546–557.

- Kumar, M.; Gupta, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Nandi, S.K.; Mandal, B.B. Immunomodulatory injectable silk hydrogels maintaining functional islets and promoting anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization. Biomaterials 2018, 187, 1–17.

- Floren, M.; Bonani, W.; Dharmarajan, A.; Motta, A.; Migliaresi, C.; Tan, W. Human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on silk hydrogels with variable stiffness and growth factor differentiate into mature smooth muscle cell phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2016, 31, 156–166.

- Xiao, L.; Lu, G.; Lu, Q.; Kaplan, D.L. Direct formation of silk nanoparticles for drug delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 2050–2057.

- Hu, X.; Shmelev, K.; Sun, L.; Gil, E.-S.; Park, S.-H.; Cebe, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Regulation of silk material structure by temperature-controlled water vapor annealing. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1686–1696.

- Dong, S.; Guo, P.; Chen, G.-y.; Jin, N.; Chen, Y. Study on the atmospheric cold plasma (ACP) treatment of zein film: Surface properties and cytocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 153, 1319–1327.

- Torculas, M.; Medina, J.; Xue, W.; Hu, X. Protein-based bioelectronics. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1211–1223.

- Jia, Z.; Zhou, W.; Yan, J.; Xiong, P.; Guo, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. Constructing multilayer silk protein/nanosilver biofunctionalized hierarchically structured 3D printed Ti6Al4 V scaffold for repair of infective bone defects. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 5, 244–261.

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yuan, Z.; You, B.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, F.; Qu, C.; Zhang, X. A novel 3D in vitro tumor model based on silk fibroin/chitosan scaffolds to mimic the tumor microenvironment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 36641–36651.

- Xue, Y.; Lofland, S.; Hu, X. Thermal conductivity of protein-based materials: A review. Polymers 2019, 11, 456.

- Guan, J.; Wang, Y.; Mortimer, B.; Holland, C.; Shao, Z.; Porter, D.; Vollrath, F. Glass transitions in native silk fibres studied by dynamic mechanical thermal analysis. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 5926–5936.

- Xue, Y.; Hu, W.; Hu, X. Thermal analysis of natural fibers. In Thermal Analysis of Textiles and Fibers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 105–132.

- DiBenedetto, A. Prediction of the glass transition temperature of polymers: A model based on the principle of corresponding states. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1987, 25, 1949–1969.

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tan, X.; Xie, X.; Dong, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q. Disruption of the metal ion environment by EDTA for silk formation affects the mechanical properties of silkworm silk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3026.

- Zong, X.-H.; Zhou, P.; Shao, Z.-Z.; Chen, S.-M.; Chen, X.; Hu, B.-W.; Deng, F.; Yao, W.-H. Effect of pH and copper (II) on the conformation transitions of silk fibroin based on EPR, NMR, and Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 11932–11941.

- Lin, G.; Zhong, Y.; Zhong, J.; Shao, Z. Effect of Fe3+ on the silk fibroin regulated direct growth of nacre-like aragonite hybrids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5774–5780.