The microbial cell–cell chemical communication systems include QS and host–pathogen communication systems. In 1994, Fuqua et al., coined the term of “quorum sensing” to describe an environmental sensing system that monitors the population density to coordinate the social behaviors of microorganisms. QS regulatory systems are characterized by the fact that microorganisms produce and release to the surrounding environment a diffffusible autoinducer or QS signal, which accumulates along with bacterial growth and induces target gene transcriptional expression when reaching a threshold concentration. Typically, a QS system contains a signal synthase, which produces QS signals, and a signal receptor that detect and response to QS signal in a population-dependent manner. In addition, microbial pathogens can also exploit the chemical molecules produced by host organisms as cross-kingdom signals to regulate virulence gene expression.

- Microbial Cell-Cell Chemical Communication Systems

- microbial communication systems

- quorum sensing

1. AHL-Type QS System

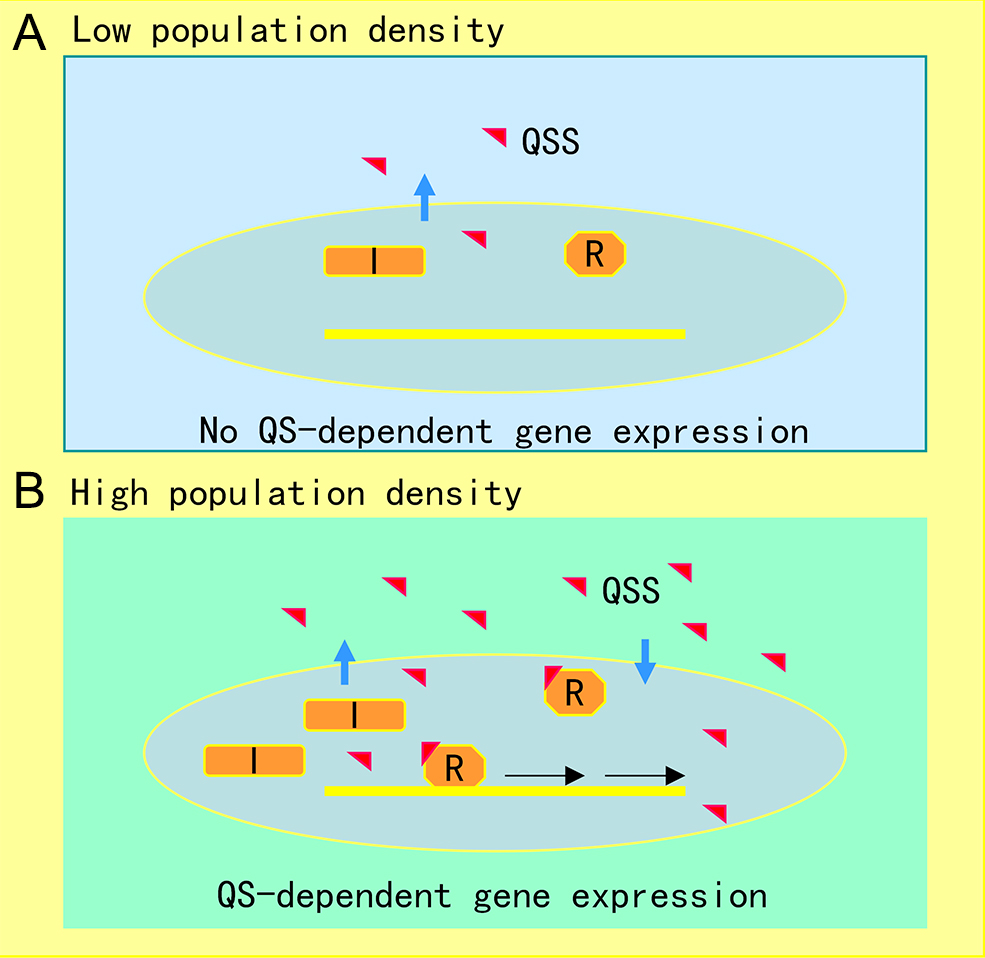

The AHL-mediated QS system is one of the most studied cell-to-cell communication systems, with over 200 bacterial species known to produce AHL family signals. Different bacterial species produce similar AHL signaling molecules with a conserved N-acyl homoserine lactone, but the fatty acid side chain lengths and substituents are in general variable, which may account for their signaling specificity in different microorganisms [1]. A wide range of microbial biological functions are known to be regulated by the AHL QS system, including bioluminescence, plasmid DNA transfer, production of pathogenic factors, biofilm formation, and antibiotic production [2]. The core of the AHL QS system consists of the AHL synthase (LuxI homologue) and the AHL signal receptor (LuxR homologue). In the bioluminescent bacterium A. fischeri, where the AHL QS system was first identified, at low cell density, the LuxI protein produces a basal level of few diffusible AHL molecules, and little bioluminescence could be detected. In contrast, with an increase in bacterial population density, the AHL signal molecules that accumulated around the bacterial cells enter the cell and bind and activate the LuxR protein, which then initiates LuxI overexpression and activates transcription of luminescence genes [3]. The generic mechanism of AHL-mediated QS is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of quorum sensing (QS) mechanism in microorganisms. (A) At low cell population density, bacterial cells produce limited QS signal (QSS) which cannot trigger QS-dependent gene expression. (B) Along with bacterial growth, accumulated QSS interacts with and hence activates its cognate receptor to induce virulence factor production, biofilm formation, and generation of efflux pumps, which aid the pathogen survival in the host by counteracting various possible stresses, including immune responses and antibiotics. Symbols: I represents the QS signal synthase, R is the receptor, and the red triangle indicates QS signal.

2. DSF-type QS system

DSF represents another class of QS systems that are widespread in Gram-negative bacteria. In 1997, the Daniels Laboratory in the UK discovered that plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv.campesitris (Xcc) could produce a diffusible signaling factor (DSF) and regulate production of a number of virulence factors, including proteases, cellulases and extracellular polysaccharides [4][5][4,5]. A subsequent study showed that three genes are associated with the DSF QS system, in which the rpfF gene may encode a DSF synthase, and the products of rpfC and rpfG genes could be involved in DSF signaling [5]. In 2004, Wang et al. isolated and identified DSF as cis-11-methyl-2-dodecenoic acid [6]. To date, more than 10 structurally similar DSF family signals have been isolated and identified from Gram-negative bacteria, and over 100 bacterial species were predicted to use DSF to regulate various biological functions [7][8][7,8]. The biological functions and signaling mechanisms of the DSF systems have been well studied in Xcc and Burkholderia cenocepacia [9][10][9,10]. In Xcc, response to DSF signals leads to activation of the protein kinase RpfC by self-phosphorylation, which activates the phosphodiesterase activity of its cognate response regulator RpfG through phosphorelay; the activated RpfG degrades c-di-GMP molecules and activates the global regulator Clp; Clp directly regulates the transcription of a number of pathogenic genes and indirectly regulates the expression of other pathogenic genes through the downstream transcription factors FhrR and Zur [9]. In B. cenocepacia, another DSF family signal, cis-2-dodecenoic acid (BDSF), binds to its major receptor RpfR to reduce the intracellular c-di-GMP to a sufficient level, which stimulate the RpfR-GtrR protein complex to bind to the promoter region of target DNA, thus modulating the production of virulence factors and biofilm mass [11][12][13][11-13].

3. Polyamine-Mediated Host–Pathogen Communication Systems

Spermidine (Spd), spermine (Spm), and putrescine (Put) represent a widespread group of cationic aliphatic compounds with multiple biological activities in living cells, collectively referred to as polyamines. In recent years, increasing evidence indicates that polyamines are capable of performing regulatory functions as signals in intraspecies cell–cell communication or are involved in host–pathogen trans-kingdom cell-cell communication [14][15][14,15]. The precursors for synthesis of Put, Spd and Spm in bacterial cells are l-arginine, l-ornithine and l-methionine, respectively [16]. l-arginine decarboxylase decarboxylates arginine to produce adamantane, which is then converted to Put and urea by agmatine ureohydrolase. l-ornithine is decarboxylated by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) to produce Put, then Put undergoes a transfer reaction with a propylamine group by the action of arginine synthetase to produce Spd, and then undergoes another transfer reaction with a propylamine group by the action of Spm synthetase to produce Spm [17]. l-methionine is catalyzed by l-methionine adenosyltransferase to produce S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which is then decarboxylated by S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SAMDC) to produce S-adenosylmethionine (dcSAM), which provides the propylamine group for the synthesis of Spd and Spm [17]. In bacteria, polyamines are mainly involved in the regulation of important physiological processes such as transcription and translation of bacterial virulence factors, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, acidic and oxidative stresses [16][18][16,18].

References

- Blevins, S.M.; Bronze, M.S. Robert Koch and the ‘golden age’ of bacteriology. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e744–e751.Dong, Y.H.; Wang, L.Y.; Zhang, L.H. Quorum-quenching microbial infections: mechanisms and implications. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2007, 362, 1201-1211, doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2045.

- Berche, P. Louis Pasteur, from crystals of life to vaccination. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18 (Suppl. 5), 1–6.Fuqua, C.; Greenberg, E.P. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002, 3, 685-695, doi:10.1038/nrm907.

- Schwartz, R.S. Paul Ehrlich’s magic bullets. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1079–1080.Dunlap, P.V.; Kuo, A. Cell density-dependent modulation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence system in the absence of autoinducer and LuxR protein. J Bacteriol 1992, 174, 2440-2448, doi:10.1128/jb.174.8.2440-2448.1992.

- Hugh, T.B. Howard Florey, Alexander Fleming and the fairy tale of penicillin. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 177, 52–53.Barber, C.E.; Tang, J.L.; Feng, J.X.; Pan, M.Q.; Wilson, T.J.; Slater, H.; Dow, J.M.; Williams, P.; Daniels, M.J. A novel regulatory system required for pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris is mediated by a small diffusible signal molecule. Mol Microbiol 1997, 24, 555-566, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3721736.x.

- Mohr, K.I. History of Antibiotics Research. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 398, 237–272.Slater, H.; Alvarez-Morales, A.; Barber, C.E.; Daniels, M.J.; Dow, J.M. A two-component system involving an HD-GYP domain protein links cell-cell signalling to pathogenicity gene expression in Xanthomonas campestris. Mol Microbiol 2000, 38, 986-1003, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02196.x.

- Waglechner, N.; McArthur, A.G.; Wright, G.D. Phylogenetic reconciliation reveals the natural history of glycopeptide antibiotic biosynthesis and resistance. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1862–1871.Wang, L.H.; He, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, J.E.; Dong, Y.H.; He, C.; Wang, S.X.; Weng, L.X.; Xu, J.L.; Tay, L., et al. A bacterial cell-cell communication signal with cross-kingdom structural analogues. Mol Microbiol 2004, 51, 903-912, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03883.x.

- Gould, K. Antibiotics: From prehistory to the present day. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 572–575.Deng, Y.; Wu, J.; Tao, F.; Zhang, L.H. Listening to a new language: DSF-based quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Chem Rev 2011, 111, 160-173, doi:10.1021/cr100354f.

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281.Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.H.; Camara, M.; He, Y.W. The DSF Family of Quorum Sensing Signals: Diversity, Biosynthesis, and Turnover. Trends Microbiol 2017, 25, 293-303, doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.013.

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910.He, Y.W.; Zhang, L.H. Quorum sensing and virulence regulation in Xanthomonas campestris. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008, 32, 842-857, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00120.x.

- Spellberg, B.; Guidos, R.; Gilbert, D.; Bradley, J.; Boucher, H.W.; Scheld, W.M.; Bartlett, J.G.; Edwards, J., Jr.; Infectious Diseases Society of, A. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: A call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 155–164.Deng, Y.; Schmid, N.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Pessi, G.; Wu, D.; Lee, J.; Aguilar, C.; Ahrens, C.H.; Chang, C., et al. Cis-2-dodecenoic acid receptor RpfR links quorum-sensing signal perception with regulation of virulence through cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 15479-15484, doi:10.1073/pnas.1205037109.

- D’Costa, V.M.; King, C.E.; Kalan, L.; Morar, M.; Sung, W.W.; Schwarz, C.; Froese, D.; Zazula, G.; Calmels, F.; Debruyne, R.; et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 2011, 477, 457–461.Deng, Y.; Lim, A.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Chen, S.; Lee, J.; Dong, Y.H.; Zhang, L.H. Cis-2-dodecenoic acid quorum sensing system modulates N-acyl homoserine lactone production through RpfR and cyclic di-GMP turnover in Burkholderia cenocepacia. BMC Microbiol 2013, 13, 148, doi:10.1186/1471-2180-13-148.

- von Wintersdorff, C.J.; Penders, J.; van Niekerk, J.M.; Mills, N.D.; Majumder, S.; van Alphen, L.B.; Savelkoul, P.H.; Wolffs, P.F. Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbial Ecosystems through Horizontal Gene Transfer. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 173.Yang, C.; Cui, C.; Ye, Q.; Kan, J.; Fu, S.; Song, S.; Huang, Y.; He, F.; Zhang, L.H.; Jia, Y., et al. Burkholderia cenocepacia integrates cis-2-dodecenoic acid and cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate signals to control virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 13006-13011, doi:10.1073/pnas.1709048114.

- Dickey, S.W.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Otto, M. Different drugs for bad bugs: Antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 457–471.Boon, C.; Deng, Y.; Wang, L.H.; He, Y.; Xu, J.L.; Fan, Y.; Pan, S.Q.; Zhang, L.H. A novel DSF-like signal from Burkholderia cenocepacia interferes with Candida albicans morphological transition. ISME J 2008, 2, 27-36, doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.76.

- Anes, J.; McCusker, M.P.; Fanning, S.; Martins, M. The ins and outs of RND efflux pumps in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 587.Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.H. Modulation of bacterial Type III secretion system by a spermidine transporter dependent signaling pathway. PLoS One 2007, 2, e1291, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001291.

- Sun, J.; Deng, Z.; Yan, A. Bacterial multidrug efflux pumps: Mechanisms, physiology and pharmacological exploitations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 254–267.Shi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhou, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, L.H. Putrescine Is an Intraspecies and Interkingdom Cell-Cell Communication Signal Modulating the Virulence of Dickeya zeae. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1950, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01950.

- Deng, Z.; Shan, Y.; Pan, Q.; Gao, X.; Yan, A. Anaerobic expression of the gadE-mdtEF multidrug efflux operon is primarily regulated by the two-component system ArcBA through antagonizing the H-NS mediated repression. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 194.Shah, P.; Swiatlo, E. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol 2008, 68, 4-16, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06126.x.

- Borlee, B.R.; Goldman, A.D.; Murakami, K.; Samudrala, R.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 75, 827–842.Tabor, C.W.; Tabor, H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev 1985, 49, 81-99.

- Chambers, J.R.; Sauer, K. Small RNAs and their role in biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 39–49.Gevrekci, A.O. The roles of polyamines in microorganisms. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2017, 33, 204, doi:10.1007/s11274-017-2370-y.