Diwali, the Festival of Lights, is one of India's most celebrated festivals, marked by joy, light, and a spirit of togetherness. Originating in ancient India, Diwali has grown beyond its religious roots to become a global celebration symbolizing victory over darkness, ignorance, and evil. While traditionally associated with Hinduism and stories from the Ramayana, Diwali is also celebrated by Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists, each community attaching its own significance and narratives to the festivities. This article traces the historical evolution of Diwali from its origins in agrarian societies to its current standing as a multicultural and global festival. It examines the religious and cultural stories associated with Diwali, the rituals and customs observed across different communities, and the festival’s role in fostering social cohesion. As Diwali has spread globally, it has taken on new meanings and variations, demonstrating the enduring appeal of this ancient festival in modern times.

- diwali

- history of diwali

- origin of diwali

- history

- origin

- festival of lights

- article

1.

IIntroduction to Diwali

Diwali, also known as Deepavali, is one of the most prominent and eagerly awaited festivals in India and is widely celebrated by people of Indian descent worldwide. Often called the "Festival of Lights," Diwali symbolizes the triumph of light over darkness and good over evil. The festival involves vibrant rituals, including lighting oil lamps (diyas), fireworks displays, sharing sweets, and participating in family and community gatherings. While rooted in ancient religious traditions, Diwali has grown to encompass multiple layers of meaning across Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, and Buddhism, each tradition lending its unique narratives and rituals to the celebration.

2. Origins of Diwali in Ancient India

The roots of Diwali can be traced back thousands of years to the agricultural societies of ancient India. In those times, communities celebrated the changing seasons and the successful harvests, which were crucial for survival. The autumn harvest season, a time of abundance and gratitude, was marked with joyous ceremonies, which laid the groundwork for what would later become Diwali. These celebrations would coincide with the end of the summer harvest, celebrating prosperity and preparing for the colder months ahead.

3. Hindu Narratives and Myths Associated with Diwali

In Hinduism, Diwali’s significance is often connected to sacred texts like the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and other ancient scriptures:

-

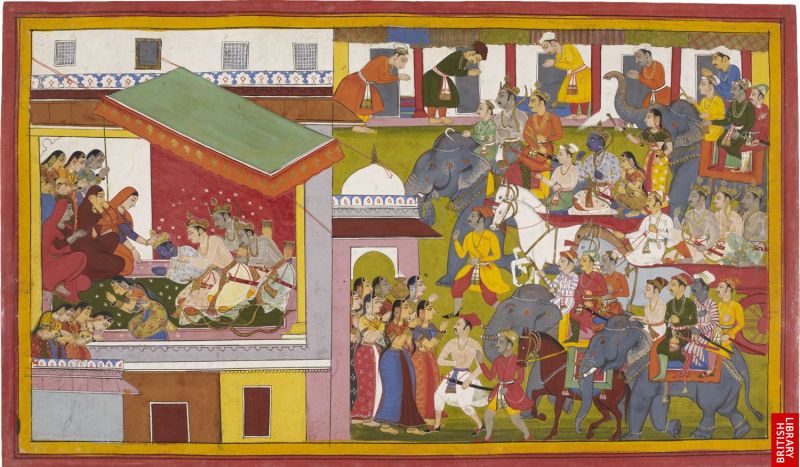

The Return of Rama: One of the most popular narratives is the return of Lord Rama to Ayodhya after a 14-year exile. According to the Ramayana, Rama, along with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana, returned to his kingdom after defeating the demon king Ravana. The people of Ayodhya welcomed him by illuminating the city with oil lamps, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil and light over darkness.

-

The Story of Krishna and Narakasura: In certain parts of India, particularly in the south, Diwali is associated with Lord Krishna’s victory over the demon Narakasura. This event, celebrated as Naraka Chaturdashi, marks the end of a tyrant and a celebration of freedom.

-

The Birth of Lakshmi: In other regions, Diwali is dedicated to Goddess Lakshmi, the deity of wealth and prosperity. According to mythology, Lakshmi was born from the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan) on the new moon day of Diwali, and she visited Earth, blessing people with prosperity. This is why many worship her during Diwali, seeking blessings for wealth and happiness.

-

Govardhan Puja and the Govardhan Hill: In certain parts of India, particularly in Gujarat and Maharashtra, the day after Diwali is celebrated as Govardhan Puja. This ritual commemorates Lord Krishna lifting Mount Govardhan to protect the villagers from torrential rains, symbolizing divine protection and humility.

4. Diwali in Other Religions

Diwali holds deep significance beyond Hinduism and is observed by Sikhs, Jains, and some Buddhists, each tradition attaching its own meanings to the festival.

-

Sikhism: For Sikhs, Diwali is celebrated as Bandi Chhor Divas, marking the release of the sixth Sikh Guru, Guru Hargobind, from imprisonment by the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1619. The Guru is said to have freed himself and 52 other princes, leading to the festival being remembered as the "Day of Liberation." The Golden Temple in Amritsar is particularly resplendent during Diwali, illuminated with thousands of lights.

-

Jainism: Jains celebrate Diwali as the day when Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara, attained Nirvana or liberation. According to Jain scriptures, Lord Mahavira achieved enlightenment on the day of Diwali. The Jain community observes this day with prayers and rituals, and many undertake a fast, reflecting on spiritual liberation and self-purification.

-

Buddhism: Diwali is celebrated by some Buddhists, particularly the Newar Buddhists in Nepal, who observe it as a festival of lights, similar to the Hindu tradition. They view it as a time to honor ancestors, light lamps, and pray for well-being and happiness.

5. Diwali Celebrations and Rituals Across India

Diwali celebrations vary across regions in India, incorporating local customs and traditions that reflect the diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

-

Northern India: In northern states, Diwali marks the return of Lord Rama to Ayodhya. The festival involves decorating homes with rangoli (colored powder designs), lighting oil lamps, and performing Lakshmi Puja. Fireworks and sweets are an integral part of the celebration, symbolizing the joy of Rama’s return and the victory of light over darkness.

-

Southern India: In southern states, Diwali often begins with the ritual of oil baths, a tradition believed to purify and rejuvenate the body. As in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, families celebrate Naraka Chaturdashi with early morning rituals, exchanging sweets, and bursting fireworks. Each ritual is associated with a specific mythological story and is meant to invoke prosperity and health.

-

Western India: In Gujarat and Maharashtra, Diwali is particularly auspicious for traders and merchants, as it coincides with the end of the financial year. On the festival day, business owners open new account books (Chopda Pujan) and seek blessings for prosperity in the coming year. The day after Diwali is celebrated as the Gujarati New Year, a day marked by traditional feasts and exchanges of good wishes.

-

Eastern India: In West Bengal, Odisha, and Assam, Diwali is celebrated as Kali Puja, dedicated to Goddess Kali, the fierce embodiment of Shakti (divine energy). Homes and temples are adorned with clay lamps and decorations to honor the goddess, invoking her protection and blessings.

6. Globalization and Diwali’s Modern Evolution

As the Indian diaspora has spread across the globe, so has the celebration of Diwali, turning it into an international festival observed by millions worldwide. In countries with large Indian populations, such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, Diwali is recognized and celebrated in public spaces, complete with parades, light displays, and community events. In recent years, several governments have officially recognized Diwali as a cultural holiday, underscoring its role in fostering multicultural inclusivity.

7. Significance of Diwali in Contemporary Society

In modern times, Diwali has grown to symbolize unity, happiness, and the spirit of giving. The festival fosters social bonding by bringing together families, communities, and friends. Amid its religious roots, Diwali also emphasizes humanitarian values like generosity, gratitude, and joy, with people donating to charities, helping those in need, and sharing food and gifts with neighbors.

8. Conclusion

Diwali, with its rich historical origins and multifaceted cultural significance, is not just a festival but a tradition deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of India and beyond. Over the centuries, Diwali has adapted to include various regional, religious, and community perspectives, making it a truly inclusive celebration. The festival’s core message—celebrating light, knowledge, and goodness—continues to resonate, drawing people from all walks of life into its luminous fold. As Diwali continues to spread globally, its universal message of triumph and togetherness remains as powerful and relevant as ever