Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Maria de los Angeles Garavagno and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is a known and persistent pollutant in the environment. Although several direct anthropogenic sources exist, production from the atmospheric degradation of fluorocarbons such as some hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) has been a known source for some time. The current transition from HFCs to HFOs (hydrofluoroolefins) is beneficial from a global warming viewpoint because HFOs are much shorter-lived and pose a much smaller threat in terms of warming, but the fraction of HFOs converted into TFA is higher than seen for the corresponding HFCs and the region in which TFA is produced is close to the source. Therefore, it is timely to review the role of TFA in the Earth’s environment.

- TFA

- HFO

- sources and sinks

- lifetime

- toxicity

1. Introduction

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, CF3COOH) is the shortest-chain species of perfluorinated carboxylic acid (PFCA) and the broader family of perfluorinated carboxylates. It is one of thousands of compounds categorized as a per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS). PFCAs include all substances that have a carboxylic group and at least one perfluoroalkyl moiety, represented by CnF2n+1 (where n ≥ 1) [1]. Many long-chain PFASs have been found to potentially cause adverse effects on human and animal health in several in vitro and in vivo studies [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], to be ubiquitous and persistent in the environment, and to bio-magnify along food chains [2][10][11][12][13][14][15][2,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Over 9000 PFASs have been identified to date and many face regulations that restrict their use because of their toxicity to humans and animals [16][17][18][19][20][21][16,17,18,19,20,21]. In view of these regulations, studies have recently shifted their focus towards shorter-chain PFASs, which are set to replace those long-chain versions most used [22][23][22,23]. In fact, many of the short-chain PFASs that are replacing more traditional long-chain PFASs are already beginning to see widespread environmental occurrence and may present similar challenges [24][25][24,25].

Unlike many other PFASs, which are non-polar and largely insoluble in water, short-chain PFASs such as TFA are highly mobile in the environment and accumulate in environmental aqueous phases due to their high solubility [26]. Current research suggests that most short-chain PFASs, including TFA, do not bioaccumulate in food chains and are rapidly excreted from humans, although some reports state that TFA has the potential to bioaccumulate in plant material [27]. A 2012 study by Russell et al. [25], sponsored by DuPont, collected measurement data for TFA in aquatic systems across the world and then carried out a detailed modelling analysis of TFA levels in aquatic systems across the USA. Comparing measured and modelled data with ecotoxicity data for freshwater algae, marine algae, aquatic plants, crustacea, and fish, they concluded that, even with rising levels of TFA predicted from the use of HFOs, aquatic life would be ‘unaffected’ by these levels of TFA [28]. Most tests on microorganisms have found that high TFA concentrations cause no harm, although one species of algae did show inhibited growth when exposed to extremely high concentrations [27]. Biological and medical research is encouraging in its unanimous findings that TFA does not bioaccumulate and exhibits low-to-moderate toxicity in a range of organisms, even in instances of very high exposure [29][30][29,30]. Furthermore, anthropogenically generated TFA is not expected to contribute significantly to acid rain or further terrestrial acidification [31]. But caution must be taken not to underestimate the impacts of TFA as its anthropogenic sources increase.

Even in the absence of evidence that TFA presents a significant risk to humans or the environment, its persistence due to its environmental stability [29][32][33][29,32,33], combined with constant or increasing emissions, will likely result in significant accumulation in the environment. TFA contamination would then be widespread, long-lasting, and difficult to remove; this would present a huge challenge if future research were to discover any detrimental effects of TFA. Indeed, TFA is already being observed in significant and increasing quantities in surface water, rain, fog, sewage treatment plants, snow, the atmosphere, and sediments [30][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][30,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. TFA rapidly dissociates into its deprotonated form, trifluoroacetate, in an aquatic environment, particularly in aqueous phases [30]. Therefore, in the context of environmental contamination, TFA salts are the most important compounds to consider. As a result, TFA and subsequent trifluoroacetate contamination have been considered in a range of international regulatory assessments conducted by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) since 1998 [30][41][30,41]. Depending on their ecological or toxicological properties, persistent substances can pose a threat to the environment as they are irrecoverable and lead to environmental pollution lasting decades to centuries, and eventually longer.

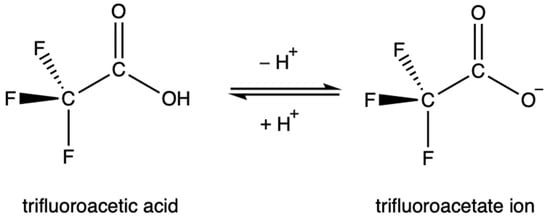

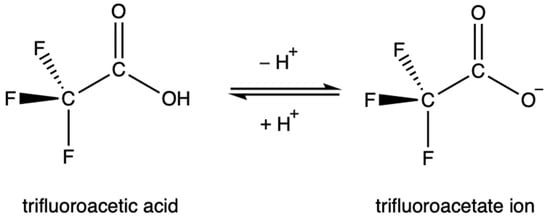

TFA is strongly acidic due to the inductive effect of the highly electronegative fluorine atoms, which draw electron density away from the carboxylate group and stabilize the anion. Similarly, the resonance of the C-F bond stabilizes the anion as electron density is distributed more evenly. The acid dissociation constant of TFA, the pKa, is contested in the literature, but is generally accepted to be between 0.2 and 0.5 [30][45][46][48][49][50][51][30,45,46,48,49,50,51]. This value is over 34,000 times more acidic than acetic acid. As a result, TFA is highly soluble in water. This rapid dissociation in aqueous solutions produces the TFA anion, known as trifluoroacetate, Figure 1. Environmentally, this means that TFA is expected to partition entirely into aqueous phases.

The trifluoroacetate anion persists in soil and environmental aqueous phases due to the high chemical and biological stability of the C-F bond [30]. TFA and its salts are highly soluble. As such, they are found in rain, fog, and water bodies, with large reservoirs present in the ocean. TFA has no known degradation pathways in environmental aqueous phases [53].

Henry’s Law describes the proportionality between the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid and the partial pressure above said liquid; this is a metric commonly used in atmospheric chemistry. The Henry’s Law constant of TFA was originally reported to be (9 ± 2) × 103 mol kg−1 atm−1 at 298 K [49]. More recently, Kutsuna et al. [46] proposed a Henry’s law constant 0.63 times smaller than that of Bowden et al. [49] when assuming pKa = 0.47, and equal to that determined by Bowden et al. [49] when assuming pKa = 0.2 [46]. The uncertainty in the pKa of TFA, arising as a result of significant variability in values reported depending on the measurement technique used, is suggested to be the main cause of discrepancies between calculated Henry’s Law constants [46]. Additionally, the solvation energy used is crucial in the calculation of pKa and reported values for this property vary significantly [46][49][46,49].

The behavior of TFA with respect to gas-to-aerosol partitioning around 298 K is likely to be similar to that discussed by Bowden et al. [49]. These authors reported that TFA in the atmosphere will partition entirely into fog and cloud water, but that partitioning into smaller amounts of liquid water, e.g., aerosol, is more complex. Here, TFA may partition into the liquid phase in alkaline aerosol, but less so as the aerosol becomes more acidic, and this idea has support in the wider literature [49][54][55][49,54,55]. Interestingly, Kazil et al. suggested that, upon cloud evaporation, dissolved TFA is released into the gas phase [54]. While the participation of TFA in aerosol formation and its ability to partition into existing aerosols is complicated, with dependencies on pH, temperature, and aerosol composition [49], research supports the contribution of TFA to aerosol formation [56]. However, a recent study demonstrated that quantifying the gas-particle-phase partitioning of TFA is particularly sensitive to predicted physical properties under atmospherically relevant conditions [55].

Using previous global model integrations as a basis for research [57] (see Supplementary Materials for more details about the integration carried out) and utilizing the global 3D chemical transport model STOCHEM-CRI, integrations have been carried out to assess the sensitivity of the global TFA burden to the choice of Henry’s Law constant. Specifically, the TFA Henry’s Law constant presented in Kutsana et al. [46] 5.7 × 101 mol m−3 Pa−1 has been used to determine the upper limits for dynamic and convective scavenging coefficients (2.2 cm−1 and 4.3 cm−1, respectively) that represent wet deposition [57]. The model used has been described elsewhere, and previously published work provides a STOCHEM-base scenario (which involves HFO-CI-HETFA, using dynamic and convective scavenging coefficients of 1.9 cm–1 and 3.8 cm–1 derived from the average of the Henry’s Law constants reported by Sander et al. [58]) for comparison [57].

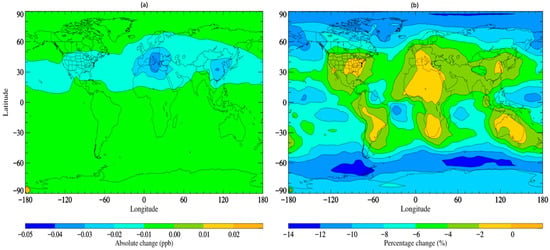

The updated simulation with altered scavenging coefficients, referred to as STOCHEM-USC, shows a small increase in the wet deposition flux of TFA by ~0.5% compared to the base scenario, with a corresponding decrease in TFA global burden of ~4.5%. Figure 2 depicts the absolute and percentage variations between the STOCHEM-base and STOCHEM-USC simulations. While a small shift is seen globally, the most significant absolute changes are found in a small section of the upper latitudes.

The trifluoroacetate anion persists in soil and environmental aqueous phases due to the high chemical and biological stability of the C-F bond [30]. TFA and its salts are highly soluble. As such, they are found in rain, fog, and water bodies, with large reservoirs present in the ocean. TFA has no known degradation pathways in environmental aqueous phases [53].

Henry’s Law describes the proportionality between the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid and the partial pressure above said liquid; this is a metric commonly used in atmospheric chemistry. The Henry’s Law constant of TFA was originally reported to be (9 ± 2) × 103 mol kg−1 atm−1 at 298 K [49]. More recently, Kutsuna et al. [46] proposed a Henry’s law constant 0.63 times smaller than that of Bowden et al. [49] when assuming pKa = 0.47, and equal to that determined by Bowden et al. [49] when assuming pKa = 0.2 [46]. The uncertainty in the pKa of TFA, arising as a result of significant variability in values reported depending on the measurement technique used, is suggested to be the main cause of discrepancies between calculated Henry’s Law constants [46]. Additionally, the solvation energy used is crucial in the calculation of pKa and reported values for this property vary significantly [46][49][46,49].

The behavior of TFA with respect to gas-to-aerosol partitioning around 298 K is likely to be similar to that discussed by Bowden et al. [49]. These authors reported that TFA in the atmosphere will partition entirely into fog and cloud water, but that partitioning into smaller amounts of liquid water, e.g., aerosol, is more complex. Here, TFA may partition into the liquid phase in alkaline aerosol, but less so as the aerosol becomes more acidic, and this idea has support in the wider literature [49][54][55][49,54,55]. Interestingly, Kazil et al. suggested that, upon cloud evaporation, dissolved TFA is released into the gas phase [54]. While the participation of TFA in aerosol formation and its ability to partition into existing aerosols is complicated, with dependencies on pH, temperature, and aerosol composition [49], research supports the contribution of TFA to aerosol formation [56]. However, a recent study demonstrated that quantifying the gas-particle-phase partitioning of TFA is particularly sensitive to predicted physical properties under atmospherically relevant conditions [55].

Using previous global model integrations as a basis for research [57] (see Supplementary Materials for more details about the integration carried out) and utilizing the global 3D chemical transport model STOCHEM-CRI, integrations have been carried out to assess the sensitivity of the global TFA burden to the choice of Henry’s Law constant. Specifically, the TFA Henry’s Law constant presented in Kutsana et al. [46] 5.7 × 101 mol m−3 Pa−1 has been used to determine the upper limits for dynamic and convective scavenging coefficients (2.2 cm−1 and 4.3 cm−1, respectively) that represent wet deposition [57]. The model used has been described elsewhere, and previously published work provides a STOCHEM-base scenario (which involves HFO-CI-HETFA, using dynamic and convective scavenging coefficients of 1.9 cm–1 and 3.8 cm–1 derived from the average of the Henry’s Law constants reported by Sander et al. [58]) for comparison [57].

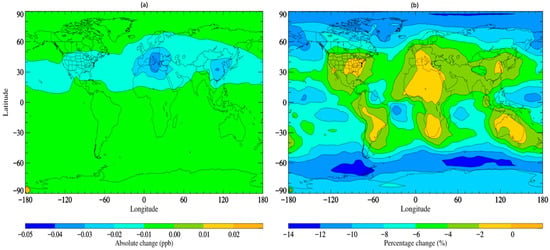

The updated simulation with altered scavenging coefficients, referred to as STOCHEM-USC, shows a small increase in the wet deposition flux of TFA by ~0.5% compared to the base scenario, with a corresponding decrease in TFA global burden of ~4.5%. Figure 2 depicts the absolute and percentage variations between the STOCHEM-base and STOCHEM-USC simulations. While a small shift is seen globally, the most significant absolute changes are found in a small section of the upper latitudes.

Areas of reduced atmospheric TFA concentrations represent areas of greater deposition and therefore higher environmental contamination.

Wet deposition is the dominant loss process for atmospheric TFA (being responsible for approximately 80% of total atmospheric TFA loss according to results published previously) [57]. Therefore, it is also the primary route to TFA environmental contamination. Given its high solubility, major concerns with TFA contamination center around environmental aqueous phases, e.g., rivers, lakes, and surface waters. As a result of pervasive TFA contamination, there have been some attempts to quantify the toxicity of TFA and its salts, particularly for species whose habitats are especially impacted.

Overall, Russell et al. reported that it is unlikely that increased TFA contamination will impair aquatic systems given the relative insensitivity of relevant organisms to TFA [28]. Similar results emerged from additional studies relating to rainwater and surface waters [37][39][84][85][37,39,87,88]; in all examples, modelled TFA proved to be below the ‘no observed effect concentration’ reported by Berends et al. [55].

Areas of reduced atmospheric TFA concentrations represent areas of greater deposition and therefore higher environmental contamination.

Wet deposition is the dominant loss process for atmospheric TFA (being responsible for approximately 80% of total atmospheric TFA loss according to results published previously) [57]. Therefore, it is also the primary route to TFA environmental contamination. Given its high solubility, major concerns with TFA contamination center around environmental aqueous phases, e.g., rivers, lakes, and surface waters. As a result of pervasive TFA contamination, there have been some attempts to quantify the toxicity of TFA and its salts, particularly for species whose habitats are especially impacted.

Overall, Russell et al. reported that it is unlikely that increased TFA contamination will impair aquatic systems given the relative insensitivity of relevant organisms to TFA [28]. Similar results emerged from additional studies relating to rainwater and surface waters [37][39][84][85][37,39,87,88]; in all examples, modelled TFA proved to be below the ‘no observed effect concentration’ reported by Berends et al. [55].

2. Physicochemical Properties

TFA (CAS: 76-05-1, MW = 114.02 g mol−1) is a colorless, volatile liquid with a distinctive odor and a density of about 1.49 g cm−3 at 25 °C. It has a melting point of approximately −15.4 °C and a boiling point between 72 and 74 °C [30][45][30,45]. It is soluble in water and various organic solvents such as methanol, ethanol, acetone, and chloroform [45]. The solubility of TFA in water has been shown to decrease with decreasing pH, as would be expected for an acidic species [46][47][46,47]. The physicochemical properties of TFA have been listed in Table 1.Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of TFA.

Figure 1.

The equilibrium between trifluoroacetic acid and its conjugate base.

Figure 2. Surface distribution plot depicting the (a) absolute and (b) percentage changes in. TFA concentrations from STOCHEM-base to STOCHEM-USC simulation.

3. Toxicity

The accumulation of TFA, or rather its deprotonated form trifluoroacetate, in environmental aqueous phases is well established; as a result, it is becoming increasingly important to consider the degree of its potential toxicity. To date, the toxicological and ecotoxicological properties of short-chain PFASs, including TFA, have arguably been only sparsely investigated [41]. Given that TFA is likely to partition in the environment into its deprotonated form, toxicity assessments are generally conducted with the anion, trifluoroacetate. Overall, the reported toxicity is low, with only one aquatic alga presenting a concerning sensitivity to TFA [59]. More generally, the resistance of aquatic plants to the effects of TFA contamination is demonstrated in several reports [60][61][60,61], with Berends et al. reporting a ‘safe’ TFA level of 0.10 mg L−1 for aquatic life [59]. While aquatic plant species are expected to be exposed to elevated TFA concentrations given its accumulation in water, terrestrial plants associated with these same water systems may also experience significant exposure [62][63][62,63]. For example, Zhang et al. reported the efficient absorption and uptake of TFA by wheat roots, with no tendency to reach a steady state [64]. Additionally, a number of studies reported that direct uptake from the atmosphere can contribute to high levels of TFA in terrestrial plant leaves [65][66][67][65,66,67]. Some terrestrial plants have been reported to bioaccumulate TFA [68], with bioconcentration factors reported to span from 4.9 to 1439 [29][65][69][70][29,65,69,70]. As a result, the toxicity they experience may be higher. The unreactive nature of TFA in the environment appears to translate into an inertness in organisms, thereby limiting its toxic effects [63]. TFA has been detected in a wide range of organisms [59][61][65][70][71][72][73][74][59,61,65,70,71,72,73,74], but a primary concern relates to its potential toxicity in humans and other mammals. A full review of the question of mammalian toxicity can be found in Dekant et al. [74], but can be summarized with the following: at the time of writing, the potential of TFA to induce toxicity in living organisms is considered to be very low. Additionally, TFA is reported to be easily excreted by mammals and so is unlikely to bioaccumulate [74][75][76][74,75,76]. Despite this, some bioaccumulation of TFA has been reported. For example, Lan et al. demonstrated the ability of TFA to bioaccumulate in a range of organisms and suggested the use of locusts as a biomonitoring tool for ecological risk assessment [70]. Additionally, a recent study reported a significant detection frequency of TFA (>90%) in the serum of 252 subjects in China [77]. The authors obtained a median concentration of 8.46 ng mL−1 across subjects and saw that TFA concentrations were correlated with age, which could suggest accumulation. However, another report suggested that the TFA concentrations measured by Duan et al. [77] might result from its metabolic generation from longer-chain PFASs, or from elevated local exposure [78]. Both the detection of metabolically generated TFA in mammals and elevated TFA exposure from certain occupational sources have been reported [79][80][81][79,80,81]. If this is the case, concentrations reported by Duan et al. [73] might not be representative of the general population. On the other hand, Zheng et al. [82] also detected TFA in human serum that was in good agreement with the values reported by Duan et al. [77]. Kim et al. have recently reported what they believe to be the first study detecting TFA in urine samples taken from the general population [83]. Later, Zheng et al. [82] reported the detection of TFA in 31% of urine samples taken, with some of the samples showing high concentrations. However, it has also been suggested that urine may not be a suitable matrix for long-term screening [83]. Overall, there is a clear need for development of a quantitative biomonitoring strategy for emerging contaminants such as TFA and further studies are urgently required.Much of the research on potential toxicity of TFA contamination has been conducted via modelling studies. Russell et al. [28] evaluated potential aquatic risk related to TFA accumulation in several modelling assessments, and predicted that after 50 years of precursor emissions, trifluoroacetate concentrations would reach 1–15 mg L−1 over most of the continental United States. Such values remain well below the nominal ecotoxicological endpoint [28]. They also modelled a ‘worst-case’ scenario of 50 years of continuous upper-bound emissions with no TFA loss in low-rainfall regions; in this instance, concentrations range between 50 and 200 mg L−1, resulting in reduced risk quotients of 5–20 [28]. This was conducted using toxicological data from Berends et al. [59] and Hanson et al. [61][73][61,73].