Le Urinfezioni del tratto urinario (UTI) sono infezioni batteriche prevalenti sia in ambito comunitario che sanitario. Rappresentano circa il 40% di tutte le infezioni batteriche e richiedono circa il 15% di tutte leary tract infections (UTIs) are prevalent bacterial infections in both community and healthcare settings. They account for approximately 40% of all bacterial infections and require around 15% of all antibiotic prescrizioni di antibiotici. Sebbene gliptions. Although antibiotici siano statis have tradizionalmente utilizzati per trattare le infezioni del tratto urinario da diversi decenni, il tionally been used to treat UTIs for several decades, the significativo aumento della resistenza aglint increase in antibiotici negli ultimi anni ha reso inefficaci molti trattamenti precedentemente efficaci. Il b resistance in recent years has made many previously effective treatments ineffective. Biofilm sulle apparecchiature mediche negli ambienti sanitari crea un serbatoio di agenti patogeni che possono essere facilmente trasmessi ai pazienti. Le infezioni dei cateteri urinari si osservanoon medical equipment in healthcare settings creates a reservoir of pathogens that can easily be transmitted to patients. Urinary catheter infections are frequentemente negli ospedali e sono causate daly observed in hospitals and are caused by microbi che formano unes that form a biofilm dopo l'inserimento di un catetere nella vescica. La gestione delle infezioni causate daiafter a catheter is inserted into the bladder. Managing infections caused by biofilm è complessa a causa dell’s is challenging due to the emergere della resistenza agli ance of antibiotici resistance.

- urinary tract infection

- nanoparticles

- multidrug resistance

- alternative strategies

1. Introduzctione

2. Classificazione e pattion and Pathogenesi delle IVUs of UTIs

2.1. Tipi di infezioni del tratto urinario

2.1. Types of UTIs

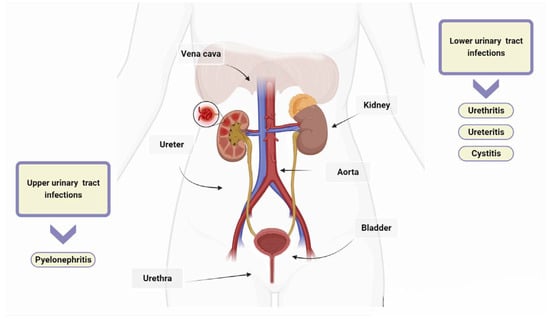

There are several classification systems for UTIs [20]. However, the most widely used systems are those developed by the CDC, which distinguish between uncomplicated and complicated UTIs on the basis of the presence of risk factors such as anatomical or functional abnormalities in the urinary tract [5,6,21][5][6][21]. UTIs are also classified according to the location of the infection and the clinical presentation of the UTI [6]. The urinary tract consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The kidneys filter waste products from the blood and produce urine, which then passes through the ureters to the bladder. UTIs are typically categorized as upper or lower depending on their location within the urinary tract. Urethritis is an inflammation of the urethra, and ureteritis is an inflammation of the ureter [22]. Lower UTIs, including cystitis, which refers to a bladder infection, and upper UTIs, such as pyelonephritis involving the kidney, are classified based on the affected area [23]. In healthy, pre-menopausal, non-pregnant women with no history of an abnormal urinary tract, acute cystitis and pyelonephritis are the classifications for uncomplicated UTIs, with women being more commonly affected than men [24]. Complicated UTIs involve functional or metabolic abnormalities, such as obstruction, urolithiasis, pregnancy, diabetes, neurogenic bladder, renal, or other immunocompromising conditions [25]. Recurrence, catheter association, and urosepsis are also included in the classification of UTIs [26]. UTIs are classified as recurrent if two or more episodes occur within six months or three or more episodes occur within 12 months [27,28][27][28]. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) account for around 75% of all hospital-acquired UTIs [29]. The risk of contracting these infections increases with prolonged use of a urinary catheter, which is a tube inserted into the bladder through the urethra to drain urine. Urosepsis is a systemic inflammatory response to UTIs such as cystitis, bladder infection, and pyelonephritis, and it can lead to multiple organ dysfunction, failure, and even death [30].2.2. Clinical Syndromes

Diagnosing UTIs can be challenging, especially in patients with non-specific symptoms [31]. However, it is crucial to differentiate between UTIs and asymptomatic bacteriuria to determine the necessity of antibiotic treatment [6]. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the presence of one or more bacterial species in urine, as indicated by a positive urine culture, in a patient who does not exhibit any signs or symptoms of a UTI (see below) [32]. In contrast, UTIs are infections that can affect the urethra, bladder, ureters, and/or kidneys. The symptoms experienced depend on which part of the urinary tract is affected [4,32][4][32]. Table 1 shows the signs and symptoms of UTIs depending on the location of the bacterial infection.| Organs of Urinary Tract | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Bladder | Dysuria *, blood in urine, frequency *, suprapubic pain |

| Urethra | Burning with urination, discharge |

| Kidneys | Nausea, vomiting, high fever, back or side pain |

| Urethritis | Dysuria *, itching, frequency * |

2.3. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Bacteria

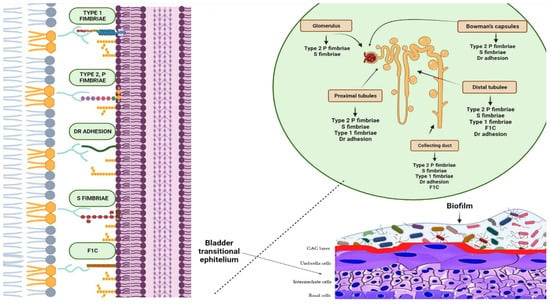

UTIs are caused by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [42]. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli is the most common pathogen found in both uncomplicated and complicated UTIs. This bacterium is responsible for at least 80% and 65% of community- and hospital-acquired UTIs, respectively [6]. For several decades, it was believed that the bladder and urethra of healthy individuals were sterile or contained too few bacteria to cause infections [43]. However, recent studies have shown evidence of numerous microorganisms in the bladder of adult humans without clinical infections. The relevance and contribution of these microorganisms to health and disease are still under investigation [43,44][43][44]. Common pathogens causing UTIs include Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Group B Streptococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and S. aureus [6]. Uropathogens express fimbrial adhesins that bind to glycolipids and glycoproteins on the mucosal–epithelial surface of the host (Figure 2) [45]. Adhesins are used by uropathogens to create biofilms on both biotic and abiotic surfaces, enabling them to colonise the mucosa of the urinary tract and indwelling devices such as urinary catheters [46]. Furthermore, some pathogens secrete substances, such as hemolysin, capsule, proteases, and phospholipases, which aid bacterial invasion by disrupting epithelial integrity [45,47,48,49,50][45][47][48][49][50]. Additionally, certain uropathogens, such as UPEC, can invade the host’s epithelial cells and replicate within them, creating a reservoir for recurrent infections [51]. This enables the bacteria to colonise and cause UTIs. Bacterial virulence factors, such as fimbriae, adhesins, P and type 1 pili, and others that facilitate bacterial invasion, have been described in detail in previous comprehensive reviews (Figure 2) [4,6,45,52][4][6][45][52].

3. The Role of Biofilm in the Persistence and Recurrence of UTIs

4. Resistance of Bacteria in Biofilm

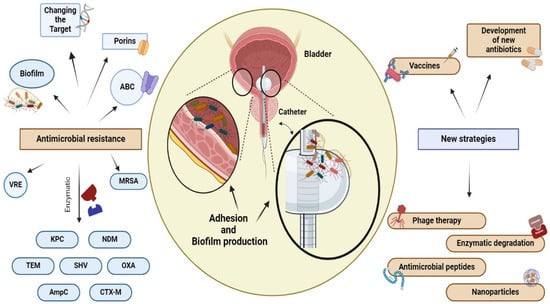

Antibiotic resistance may be significantly higher in uropathogens that reside in biofilms, up to 1000 times higher than in planktonic bacteria [83][65]. Biofilms produced by uropathogens play a crucial role in antibiotic resistance through several mechanisms (Figure 3). (1) Antibiotics diffuse inadequately within the biofilm due to the extracellular matrix, causing delayed penetration and reduced effectiveness; (2) bacteria within biofilms exhibit increased expression of efflux pumps compared to that of planktonic cells, which contributes to their resilient resistance to antibiotics; (3) the close cell-to-cell contact within biofilms facilitates the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes through HGT [16,83][16][65]. HGT facilitates the transfer of transposons and other mobile genetic elements between biofilm-forming cells, leading to the dissemination of resistance markers [75][56]. These markers encode the secretion of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes and other virulence factors. (4) The presence of slow-growing persister cells that are intrinsically resistant to antibiotics represents a reservoir of surviving cells capable of rebuilding the biofilm population [84][66]. The effectiveness of antibiotics is often limited by various mechanisms within a biofilm, which, in turn, drives antibiotic resistance, a topic that has been extensively investigated in many previous studies [6,16,46][6][16][46].

References

- Maddali, N.; Cantin, A.; Koshy, S.; Eiting, E.; Fedorenko, M. Antibiotic prescribing patterns for adult urinary tract infections within emergency department and urgent care settings. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 464–471.

- Brodie, A.; El-Taji, O.; Jour, I.; Foley, C.; Hanbury, D. A Retrospective Study of Immunotherapy Treatment with Uro-Vaxom (OM-89(R)) for Prophylaxis of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Curr. Urol. 2020, 14, 130–134.

- Medina, M.; Castillo-Pino, E. An introduction to the epidemiology and burden of urinary tract infections. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2019, 11, 1756287219832172.

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284.

- Biondo, C. New Insights into the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1213.

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Marra, M.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. Urinary Tract Infections: The Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Pathogens 2023, 12, 623.

- Goebel, M.C.; Trautner, B.W.; Grigoryan, L. The Five Ds of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship for Urinary Tract Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e0000320.

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910.

- Paul, R. State of the Globe: Rising Antimicrobial Resistance of Pathogens in Urinary Tract Infection. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2018, 10, 117–118.

- Walsh, T.R.; Gales, A.C.; Laxminarayan, R.; Dodd, P.C. Antimicrobial Resistance: Addressing a Global Threat to Humanity. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004264.

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Zummo, S.; Gerace, E.; Scappatura, G.; Biondo, C. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase & carbapenemase-producing fermentative Gram-negative bacilli in clinical isolates from a University Hospital in Southern Italy. New Microbiol. 2021, 44, 227–233.

- Li, X.; Fan, H.; Zi, H.; Hu, H.; Li, B.; Huang, J.; Luo, P.; Zeng, X. Global and Regional Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections in 2019. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2817.

- Antimicrobial Resistance, C. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655.

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310.

- Mlugu, E.M.; Mohamedi, J.A.; Sangeda, R.Z.; Mwambete, K.D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of uropathogens with biofilm forming capacity among outpatients in morogoro, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 660.

- Uruen, C.; Chopo-Escuin, G.; Tommassen, J.; Mainar-Jaime, R.C.; Arenas, J. Biofilms as Promoters of Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance and Tolerance. Antibiotics 2020, 10, 3.

- Vestby, L.K.; Gronseth, T.; Simm, R.; Nesse, L.L. Bacterial Biofilm and its Role in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 59.

- Lila, A.S.A.; Rajab, A.A.H.; Abdallah, M.H.; Rizvi, S.M.D.; Moin, A.; Khafagy, E.S.; Tabrez, S.; Hegazy, W.A.H. Biofilm Lifestyle in Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Life 2023, 13, 148.

- Hola, V.; Opazo-Capurro, A.; Scavone, P. Editorial: The Biofilm Lifestyle of Uropathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 763415.

- Tan, C.W.; Chlebicki, M.P. Urinary tract infections in adults. Singap. Med. J. 2016, 57, 485–490.

- Sihra, N.; Goodman, A.; Zakri, R.; Sahai, A.; Malde, S. Nonantibiotic prevention and management of recurrent urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 750–776.

- Li, J.; Yu, Y.F.; Qi, X.W.; Du, Y.; Li, C.Q. Immune-related ureteritis and cystitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Case report and literature review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1051577.

- Mahyar, A.; Ayazi, P.; Farzadmanesh, S.; Sahmani, M.; Oveisi, S.; Chegini, V.; Esmaeily, S. The role of zinc in acute pyelonephritis. Infez. Med. 2015, 23, 238–242.

- Van Eyssen, S.R.; Samarkina, A.; Isbilen, O.; Zeden, M.S.; Volkan, E. FimH and Type 1 Pili Mediated Tumor Cell Cytotoxicity by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli In Vitro. Pathogens 2023, 12, 751.

- Alelign, T.; Petros, B. Kidney Stone Disease: An Update on Current Concepts. Adv. Urol. 2018, 2018, 3068365.

- Werneburg, G.T. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Res. Rep. Urol. 2022, 14, 109–133.

- Ingram, A.; Posid, T.; Pandit, A.; Rose, J.; Amin, S.; Bellows, F. Risk factors, demographic profiles, and management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections: A single institution study. Menopause 2021, 28, 943–948.

- Zare, M.; Vehreschild, M.; Wagenlehner, F. Management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections. BJU Int. 2022, 129, 668–678.

- Mekonnen, S.A.; El Husseini, N.; Turdiev, A.; Carter, J.A.; Belew, A.T.; El-Sayed, N.M.; Lee, V.T. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa progresses through acute and chronic phases of infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2209383119.

- Guliciuc, M.; Porav-Hodade, D.; Mihailov, R.; Rebegea, L.F.; Voidazan, S.T.; Ghirca, V.M.; Maier, A.C.; Marinescu, M.; Firescu, D. Exploring the Dynamic Role of Bacterial Etiology in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Medicina 2023, 59, 1686.

- Woodford, H.J.; George, J. Diagnosis and management of urinary infections in older people. Clin. Med. 2011, 11, 80–83.

- Geerlings, S.E. Clinical Presentations and Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 4–5.

- Ebell, M.H.; Gagyor, I. Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection in Women. Am. Fam. Physician 2022, 106, 335–336.

- Kwok, M.; McGeorge, S.; Mayer-Coverdale, J.; Graves, B.; Paterson, D.L.; Harris, P.N.A.; Esler, R.; Dowling, C.; Britton, S.; Roberts, M.J. Guideline of guidelines: Management of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. BJU Int. 2022, 130 (Suppl. S3), 11–22.

- Caretto, M.; Giannini, A.; Russo, E.; Simoncini, T. Preventing urinary tract infections after menopause without antibiotics. Maturitas 2017, 99, 43–46.

- Alperin, M.; Burnett, L.; Lukacz, E.; Brubaker, L. The mysteries of menopause and urogynecologic health: Clinical and scientific gaps. Menopause 2019, 26, 103–111.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Byren, I.; Hoey, C.T. Treatment of bacterial prostatitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1641–1652.

- Le, B.; Schaeffer, A.J. Chronic prostatitis. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2011, 2011, 1802.

- Sell, J.; Nasir, M.; Courchesne, C. Urethritis: Rapid Evidence Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 553–558.

- Sadoghi, B.; Kranke, B.; Komericki, P.; Hutterer, G. Sexually transmitted pathogens causing urethritis: A mini-review and proposal of a clinically based diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 931765.

- Herness, J.; Buttolph, A.; Hammer, N.C. Acute Pyelonephritis in Adults: Rapid Evidence Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 173–180.

- Kline, K.A.; Lewis, A.L. Gram-Positive Uropathogens, Polymicrobial Urinary Tract Infection, and the Emerging Microbiota of the Urinary Tract. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 459–502.

- Roth, R.S.; Liden, M.; Huttner, A. The urobiome in men and women: A clinical review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 1242–1248.

- Colella, M.; Topi, S.; Palmirotta, R.; D’Agostino, D.; Charitos, I.A.; Lovero, R.; Santacroce, L. An Overview of the Microbiota of the Human Urinary Tract in Health and Disease: Current Issues and Perspectives. Life 2023, 13, 1486.

- Govindarajan, D.K.; Kandaswamy, K. Virulence factors of uropathogens and their role in host pathogen interactions. Cell Surf. 2022, 8, 100075.

- Sharma, S.; Mohler, J.; Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1614.

- Qin, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, C.; Pu, Q.; Deng, X.; Lan, L.; Liang, H.; Song, X.; Wu, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 199.

- Flores-Diaz, M.; Monturiol-Gross, L.; Naylor, C.; Alape-Giron, A.; Flieger, A. Bacterial Sphingomyelinases and Phospholipases as Virulence Factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 597–628.

- Singh, V.; Phukan, U.J. Interaction of host and Staphylococcus aureus protease-system regulates virulence and pathogenicity. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 585–607.

- Ramirez-Larrota, J.S.; Eckhard, U. An Introduction to Bacterial Biofilms and Their Proteases, and Their Roles in Host Infection and Immune Evasion. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 306.

- Whelan, S.; Lucey, B.; Finn, K. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)-Associated Urinary Tract Infections: The Molecular Basis for Challenges to Effective Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2169.

- Sarshar, M.; Behzadi, P.; Ambrosi, C.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Scribano, D. FimH and Anti-Adhesive Therapeutics: A Disarming Strategy against Uropathogens. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 397.

- Khan, J.; Tarar, S.M.; Gul, I.; Nawaz, U.; Arshad, M. Challenges of antibiotic resistance biofilms and potential combating strategies: A review. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 169.

- Abdelhamid, A.G.; Yousef, A.E. Combating Bacterial Biofilms: Current and Emerging Antibiofilm Strategies for Treating Persistent Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1005.

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Microbial biofilm: Formation, architecture, antibiotic resistance, and control strategies. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1701–1718.

- Michaelis, C.; Grohmann, E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 328.

- Tao, S.; Chen, H.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Liang, W. The Spread of Antibiotic Resistance Genes In Vivo Model. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 3348695.

- Rubi, H.; Mudey, G.; Kunjalwar, R. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI). Cureus 2022, 14, e30385.

- Palusiak, A. Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae as pathogens capable of causing co-infections and exhibiting similarities in their virulence factors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 991657.

- Cortese, Y.J.; Wagner, V.E.; Tierney, M.; Devine, D.; Fogarty, A. Review of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections and In Vitro Urinary Tract Models. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 2986742.

- Kanti, S.P.Y.; Csoka, I.; Jojart-Laczkovich, O.; Adalbert, L. Recent Advances in Antimicrobial Coatings and Material Modification Strategies for Preventing Urinary Catheter-Associated Complications. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2580.

- Stahlhut, S.G.; Struve, C.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Reisner, A. Biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae on urethral catheters requires either type 1 or type 3 fimbriae. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 350–359.

- Taha, H.; Raji, S.J.; Khallaf, A.; Abu Hija, S.; Mathew, R.; Rashed, H.; Du Plessis, C.; Allie, Z.; Ellahham, S. Improving Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection Rates in the Medical Units. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 2017, 6, u209593-w7966.

- Van Decker, S.G.; Bosch, N.; Murphy, J. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection reduction in critical care units: A bundled care model. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001534.

- Shrestha, L.B.; Baral, R.; Khanal, B. Comparative study of antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation among Gram-positive uropathogens isolated from community-acquired urinary tract infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 957–963.

- Verderosa, A.D.; Totsika, M.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E. Bacterial Biofilm Eradication Agents: A Current Review. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 824.