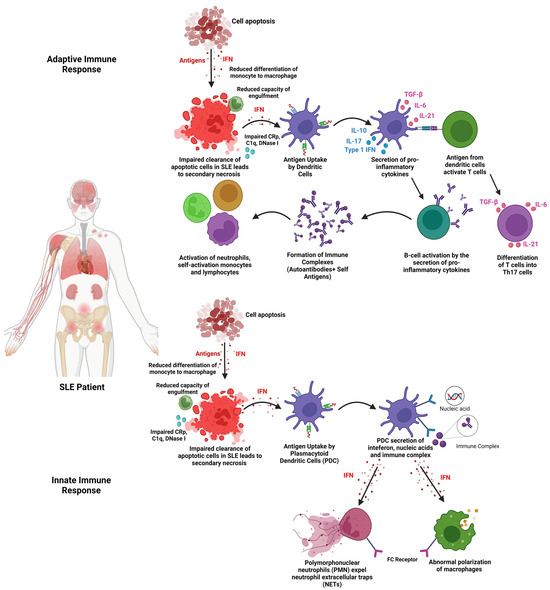

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic autoimmune disease that affects nearly 3.41 million people globally, with 90% of the cases affecting women of childbearing age. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) can reduce the pro-inflammatory cytokines and increase the anti-inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, EVs can increase the levels of regulatory T cells, thus reducing inflammation. EVs also have the potential to regulate B cells to alleviate SLE and reduce its adverse effects.

- extracellular vesicles (EVs)

- immunomodulation

- inflammation

- mesenchymal stromal cells

- systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- autoimmune

1. Introduction

2. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

3. Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

3.1. Isolation of EVs

The isolation method of EVs is crucial to obtain the possible highest purity of EVs to further enhance the specific mechanism of action required [22]. In all the studies, EVs were isolated from the supernatant only after reaching 80–90% confluency of MSCs. The supernatant derived from the conditioned media undergoes centrifugation between 10,000× g and 125,000× g and further undergoes ultracentrifugation at 140,000× g to isolate the EVs based on the size from the precipitate obtained [43][37]. Apart from that, some studies have included EVs that are also isolated from supernatants using super high-speed centrifugation of 175,000× g. There are other studies that have stated the use of only ultracentrifugation between 125,000× g and 140,000× g for the isolation of EVs [1,44,45,46,47][1][38][39][40][41].

3.2. Characterisation of EVs

The isolated EVs are required to be characterised based on their size and specific EV markers to identify the protein expressed by the EVs [43][37]. From the studies, the common characterisation method of EVs is the Western blot assay. The Western blot assay is used to determine specific protein markers related to EVs, which are commonly identified as CD9, CD36, and endoplasmic reticulum-oriented calnexin [43][37]. Other protein markers found in the selected studies that were used to identify and characterise EVs include CD63, Alix, CD81, CD63, GAPDH, and TSG101 [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]. Characterisation of EVs based on morphology was conducted using a transmission electron microscope and was recorded in a few of the studies. The morphology of EVs that were reported in the studies includes EVs shaped like a saucer, round, or sphere-shaped vesicles that include an entire capsule, bilayer-membrane structure, and a hollow globular vesicle [1,43,44,45,49,51][1][37][38][39][43][45]. Apart from that, most studies included the characterisation of EVs by size, using either a nanoparticle tracking analyser or a particle tracking assay [1,43,44,45,50][1][37][38][39][44]. However, some studies included a different characterisation method to understand the uptake of EVs using the ExoGlow-Protein EV labelling kit-(Green, System Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA, USA) that dyes EVs fluorescent green [51][45]. The study involving SHED-EVs reported a unique characterisation method based on the Ag expression on the surface of the EVs that were analysed using ExoAB Ab kit (System Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA) and R-PE-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG Ab (Cell Signalling Technology, Dancers, MA) using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) [50][44].3.3. Range of Dose of EVs Administered

To investigate the efficacy of EV treatment for SLE in in vivo models, the dose of EVs required is an important factor that can determine the immunomodulation effects in SLE. In the study of Chen et al. [43][37] and Chen et al. [46][40], the mice were injected with 100 μL of 0.2 mg/mL EVs derived from hUC-MSCs via intravenous injection through the tail vein every 2 days for 14 days. Instead of 2 days, the study carried out by Wei et al. [48][42] reported 2 × 105 cells per 10 g animal weight of ADSC/miR-20a per 150 μL PBS solution weekly for 14 days. Instead of multiple injections of EVs, a study by Sun et al. [47][41] recorded single doses of EVs of 200 μg based on the protein concentration that were administered.3.4. Mechanism of Action (EVs)

3.4.1. Effects of EVs on Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

The immunomodulatory characteristics of EVs have championed the role of EVs in downregulating disease progression of SLE through various pathways and mechanisms. In terms of macrophage polarisation, in the study by Chen et al. [43][37], EVs derived from hUC-MSCs are involved in decreasing the levels of NOTCH1, IL-1β, and iNOS which are markers indicating activation of the M1 phenotype (pro-inflammatory). Specifically, the iNOS marker was also downregulated when BM-MSC EVs were used [51][45]. The effect of EVs on macrophage polarisation is also proven in the study by Dou et al. [49][43], where EVs derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) decreased the polarisation of macrophage into the M1 phenotype. The expression of CD80, NOS2, and MCP-1, which are protein expression markers in M1 macrophages, was significantly decreased.3.4.2. Effects of EVs on Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

Moreover, the EVs played a pivotal role in increasing the CD206, CD86+, CD116+, Arginase-1, and IL-10, which are part of markers indicating M2 macrophage polarisation leading to anti-inflammatory effects [43,46][37][40]. CD206+ and CD163+ markers can also be seen to be upregulated in the study carried out by Sun et al. [47][41] using UC-MSCs to inhibit lupus via M2 macrophage polarisation. The upregulation of Arg-1 markers is also recorded in the study carried out by Zhang et al. [51][45] involving EVs derived from BM-MSCs. The study by Dou et al. [49][43] also recorded an upregulation of CD206, MRC-2, and ARG-1, which are M2 macrophage markers indicating an anti-inflammatory response. Different markers of M2 macrophage, such as CD14+ and CD163+, were alleviated and recorded in the study by Sun et al. [47][41].3.4.3. Effects of EVs on T Cell Lineage

Apart from the secretion of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines, EVs have proven to be involved in the regulation of Treg and T helper cells to suppress the disease progression of SLE. In the study by Tu et al. [44][38], Th17 subsets were significantly downregulated, showing a reduction in pro-inflammation effects. The cytokine level IL-17 co-relates to the production of Th17 cells. Lower levels of IL-17 indicate lower production of Th17 cells, as IL-17 acts as a biomarker to examine the disease activity in SLE patients [54][46].3.4.4. Effects of EVs on B Cells

Having said that, EVs also have the potential to regulate B cells, which was recorded in the study carried out by Zhao et al. [45][39], which further confirms immunomodulation effects via B cells. EVs have been shown to increase the levels of B cell apoptosis while inhibiting the excessive proliferation of B cells. Cytokine levels further confirmed that the hyperactivation of B cells reduced significantly after the treatment with EVs.3.4.5. Effects of EVs on Lupus Nephritis (c-Complements)

Furthermore, SLE can also lead to complications such as lupus nephritis, which is caused by kidney inflammation. EVs were also reported in various studies, proving to have positive effects by alleviating inflammation and its effects on the kidneys. In the study by Wei et al. [48][42] and Zhang et al. [51][45], levels of IgG and C3, which are immune complexes, were significantly downregulated in the glomerular mesangial and endocapillary of the kidney after the treatment with EVs.3.5. Role of miRNAs and tsRNAs in Extracellular Vesicles in Ameliorating the Disease Progression of SLE

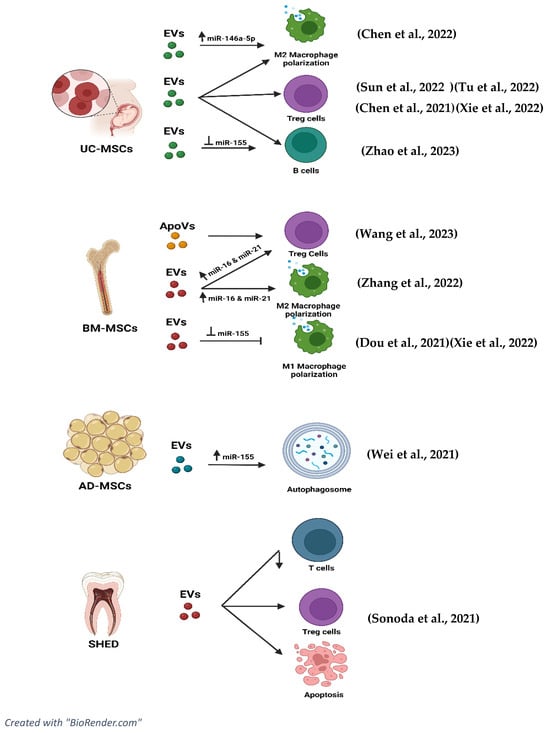

To further improve or understand the immunomodulatory effects of EVs, the effectiveness of inhibition and overexpression of miRNAs related to EVs are included in the studies and shown in Figure 32. The study by Chen et al. [43][37] indicated that the inhibition of miR-146a-5p resulted in adverse effects on lung injuries. NOTCH1, IL-1β, and iNOS were overexpressed while IL-10 and TGF-β levels were downregulated. The inhibition produced a negative effect, thus proving that expression of miR-146a-5p in EVs can upregulate IL-10, CD206, Arg-1, and TGF-β and decrease the expression of NOTCH1, IL-1β, and iNOS in patients diagnosed with SLE.

3.6. EVs and Signalling Pathways

It is important to understand the effects of EVs and their specific miRNA and tsRNA on the pathway that is involved in the disease progression of SLE. This is to ensure further understanding of the mechanism of action of EVs in immunomodulation. In the study by Chen et al. [43][37], the NOTCH 1 pathway was identified to play a crucial role in macrophage polarisation into the M1 phenotype. Apart from the NOTCH 1 pathway, inhibition of the MAPK/ERK signalling pathway plays an essential role in regulating B cells and inhibiting B cell overactivation in SLE patients. The SHIP-1 protein levels have a direct effect on the ERK signalling pathway. To prove the mechanism of action of EVs through this pathway, miR-155 was inhibited in B cells through EVs. The inhibition of miR-155 increased the expression of SHIP-1 proteins. Increased levels of SHIP-1 protein inhibit the ERK signalling pathway, thus reducing B cell proliferation and activation while increasing B cell apoptosis [45][39]. Other inflammatory-related pathways that were included in the studies include the T cell receptor signalling pathway. The TCR pathway is involved in the regulation of cytokines, survival of T cells, proliferation, and differentiation of T cells. Dysregulation of this pathway can increase the chances of developing SLE [57][48].References

- Xie, M.; Li, C.; She, Z.; Wu, F.; Mao, J.; Hun, M.; Luo, S.; Wan, W.; Tian, J.; Wen, C. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived extracellular vesicles regulate acquired immune response of lupus mouse in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13101.

- Justiz Vaillant, A.A.; Goyal, A.; Varacallo, M. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Kuhn, A.; Bonsmann, G.; Anders, H.-J.; Herzer, P.; Tenbrock, K.; Schneider, M. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 423–432.

- Kamen, D.L. Environmental influences on systemic lupus erythematosus expression. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 40, 401–412.

- Kernder, A.; Richter, J.G.; Fischer-Betz, R.; Winkler-Rohlfing, B.; Brinks, R.; Aringer, M.; Schneider, M.; Chehab, G. Delayed diagnosis adversely affects outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus: Cross sectional analysis of the LuLa cohort. Lupus 2021, 30, 431–438.

- Imran, S.; Thabah, M.M.; Azharudeen, M.; Ramesh, A.; Bobby, Z.; Negi, V.S. Liver Abnormalities in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Prospective Observational Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e15691.

- Chen, S.-L.; Zheng, H.-J.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Xu, Q.; Lin, C.-S. Case report: Joint deformity associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e717.

- Sequeira, J.F.; Cesic, D.; Keser, G.; Bukelica, M.; Karanagnostis, S.; Khamashta, M.A.; Hughes, G.R. Allergic disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 1993, 2, 187–191.

- Wuthisiri, W.; Lai, Y.H.; Capasso, J.; Blidner, M.; Salz, D.; Kruger, E.; Levin, A.V. Autoimmune retinopathy associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: A diagnostic dilemma. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 7, 172–176.

- Abu Bakar, F.; Sazliyana Shaharir, S.; Mohd, R.; Mohamed Said, M.S.; Rajalingham, S.; Wei Yen, K. Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on Work Productivity and Daily Living Activity: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Malaysian Multi-Ethnic Cohort. Arch. Rheumatol. 2020, 35, 205–213.

- Mohamed, M.H.; Gopal, S.; Idris, I.B.; Aizuddin, A.N.; Miskam, H.M. Mental Health Status Among Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients at Tertiary Hospital in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Work. J. 2020, 5, 30–39.

- Fava, A.; Petri, M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and clinical management. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 96, 1–13.

- Kaul, A.; Gordon, C.; Crow, M.K.; Touma, Z.; Urowitz, M.B.; van Vollenhoven, R.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Hughes, G. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16039.

- Pan, L.; Lu, M.-P.; Wang, J.-H.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.-R. Immunological pathogenesis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. World J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 19–30.

- McKeon, K.P.; Jiang, S.H. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Aust. Prescr. 2020, 43, 85–90.

- Sakthiswary, R.; Suresh, E. Methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review of its efficacy. Lupus 2014, 23, 225–235.

- Zhang, K.; Liu, L.; Shi, K.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, C.; Jin, Y. Extracellular Vesicles for Immunomodulation in Tissue Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2022, 28, 393–404.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, aau6977.

- Song, Y.; Kim, Y.; Ha, S.; Sheller-Miller, S.; Yoo, J.; Choi, C.; Park, C.H. The emerging role of exosomes as novel therapeutics: Biology, technologies, clinical applications, and the next. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13329.

- Battistelli, M.; Falcieri, E. Apoptotic Bodies: Particular Extracellular Vesicles Involved in Intercellular Communication. Biology 2020, 9, 21.

- Huldani, H.; Jasim, S.A.; Bokov, D.O.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Shalaby, M.N.; Thangavelu, L.; Margiana, R.; Qasim, M.T. Application of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells as potential therapeutic tools in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 106, 108634.

- Gurunathan, S.; Kang, M.-H.; Jeyaraj, M.; Qasim, M.; Kim, J.-H. Review of the Isolation, Characterization, Biological Function, and Multifarious Therapeutic Approaches of Exosomes. Cells 2019, 8, 307.

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chu, L.; Han, X.; Galons, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; et al. Exosomes from different cells: Characteristics, modifications, and therapeutic applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112784.

- Silva, T.A.; Smuczek, B.; Valadão, I.C.; Dzik, L.M.; Iglesia, R.P.; Cruz, M.C.; Zelanis, A.; de Siqueira, A.S.; Serrano, S.M.T.; Goldberg, G.S.; et al. AHNAK enables mammary carcinoma cells to produce extracellular vesicles that increase neighboring fibroblast cell motility. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 49998–50016.

- Ozawa, P.M.M.; Alkhilaiwi, F.; Cavalli, I.J.; Malheiros, D.; de Souza Fonseca Ribeiro, E.M.; Cavalli, L.R. Extracellular vesicles from triple-negative breast cancer cells promote proliferation and drug resistance in non-tumorigenic breast cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 172, 713–723.

- Stronati, E.; Conti, R.; Cacci, E.; Cardarelli, S.; Biagioni, S.; Poiana, G. Extracellular Vesicle-Induced Differentiation of Neural Stem Progenitor Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3691.

- Jiang, J.; Mei, J.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yi, S.; Feng, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Tumor hijacks macrophages and microbiota through extracellular vesicles. Exploration 2022, 2, 20210144.

- Pitt, J.M.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L. Extracellular vesicles: Masters of intercellular communication and potential clinical interventions. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1139–1143.

- Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, C. A review of the regulatory mechanisms of extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 77.

- Yekula, A.; Muralidharan, K.; Kang, K.M.; Wang, L.; Balaj, L.; Carter, B.S. From laboratory to clinic: Translation of extracellular vesicle based cancer biomarkers. Methods 2020, 177, 58–66.

- Reed, S.L.; Escayg, A. Extracellular vesicles in the treatment of neurological disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 157, 105445.

- Akbar, N.; Azzimato, V.; Choudhury, R.P.; Aouadi, M. Extracellular vesicles in metabolic disease. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2179–2187.

- Zhu, L.; Kalimuthu, S.; Oh, J.M.; Gangadaran, P.; Baek, S.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.; Ahn, B.-C. Enhancement of antitumor potency of extracellular vesicles derived from natural killer cells by IL-15 priming. Biomaterials 2019, 190–191, 38–50.

- Bruno, S.; Collino, F.; Deregibus, M.C.; Grange, C.; Tetta, C.; Camussi, G. Microvesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit tumor growth. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 758–771.

- Katsuda, T.; Oki, K.; Ochiya, T. Potential application of extracellular vesicles of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. In Renewal and Cell-Cell Communication; Turksen, K., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1212, pp. 171–181.

- Cosenza, S.; Toupet, K.; Maumus, M.; Luz-Crawford, P.; Blanc-Brude, O.; Jorgensen, C.; Noël, D. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes are more immunosuppressive than microparticles in inflammatory arthritis. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1399–1410.

- Chen, X.; Su, C.; Wei, Q.; Sun, H.; Xie, J.; Nong, G. Exosomes Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Mice by Promoting M2 Macrophage Polarization via the microRNA-146a-5p/NOTCH1 Axis. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 1975–1993.

- Tu, J.; Zheng, N.; Mao, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L. UC-BSCs Exosomes Regulate Th17/Treg Balance in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus via miR-19b/KLF13. Cells 2022, 11, 4123.

- Zhao, Y.; Song, W.; Yuan, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Diao, B. Exosome Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Cell Exerts Immunomodulatory Effects on B Cells from SLE Patients. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 3177584.

- Chen, X.; Wei, Q.; Sun, H.M.; Zhang, X.B.; Yang, C.R.; Tao, Y.; Nong, G.M. Exosomes Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulate Macrophage Polarization to Attenuate Systemic Lupus Erythematosus-Associated Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage in Mice. Int. J. Stem Cells 2021, 14, 331–340.

- Sun, W.; Yan, S.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, M.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells-derived Exosomes Ameliorate Lupus by Inducing M2 Macrophage Polarization and Regulatory T Cell Expansion in MRL/lpr Mice. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 1785–1803.

- Wei, S.S.; Zhang, Z.W.; Yan, L.; Mo, Y.J.; Qiu, X.W.; Mi, X.B.; Lai, K. miR-20a Overexpression in Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes Therapeutic Efficacy in Murine Lupus Nephritis by Regulating Autophagy. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 3746335.

- Dou, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, P.; Yan, B. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomal tsRNA-21109 alleviate systemic lupus erythematosus by inhibiting macrophage M1 polarization. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 139, 106–114.

- Sonoda, S.; Murata, S.; Kato, H.; Zakaria, F.; Kyumoto-Nakamura, Y.; Uehara, N.; Yamaza, H.; Kukita, T.; Yamaza, T. Targeting of Deciduous Tooth Pulp Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on Telomerase-Mediated Stem Cell Niche and Immune Regulation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 3053–3063.

- Zhang, M.; Johnson-Stephenson, T.K.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Zen, K.; Chen, X.; Zhu, D. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome-educated macrophages alleviate systemic lupus erythematosus by promoting efferocytosis and recruitment of IL-17+ regulatory T cell. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 484.

- Nordin, F.; Shaharir, S.S.; Abdul Wahab, A.; Mustafar, R.; Abdul Gafor, A.H.; Mohamed Said, M.S.; Rajalingham, S.; Shah, S.A. Serum and urine interleukin-17A levels as biomarkers of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 22, 1419–1426.

- Wang, R.; Hao, M.; Kou, X.; Sui, B.; Sanmillan, M.L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Tian, J.; Yu, W.; Chen, C.; et al. Apoptotic vesicles ameliorate lupus and arthritis via phosphatidylserine-mediated modulation of T cell receptor signaling. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 25, 472–484.

- Shah, K.; Al-Haidari, A.; Sun, J.; Kazi, J.U. T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 412.