Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Kevin Wu and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Eating disorders are a group of psychiatric conditions that involve pathological relationships between patients and food. The most prolific of these disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.

- eating disorders

- anorexia nervosa

- bulimia nervosa

1. Introduction

Eating disorders are psychiatric conditions primarily characterized by disturbances in eating behaviors as well as in thoughts and emotions related to eating. Individuals suffering from these disorders experience disordered beliefs related to weight and body image, which can lead to severe psychological and physical harm [1]. The most common of these disorders, and the primary focus of this paper, are anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED).

AN is a disorder related to an extreme fear of weight gain and a distorted view of one’s own body, often leading an individual to take extreme measures to maintain or lose weight [2]. The pathologic behaviors exhibited by patients with AN include excessive physical activity, extreme dietary restriction, and purging [2]. Additionally, this disorder can impact an individual’s cognitive and emotional functioning and is often accompanied by medical and psychiatric comorbidities [2], such as bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders, as well as life-threatening conditions, including amenorrhea, vital sign abnormalities, malnutrition, the loss of bone mineral density, and abnormal lab findings [1]. AN has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 0.3% [3].

BN involves recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by subsequent inappropriate actions to avoid weight gain from the binge eating episode [4]. These compensatory methods can be harmful and may include self-induced vomiting, laxatives, or prolonged periods of starvation [5]. The psychiatrist Gerald Russell differentiated patients suffering from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa by describing those with BN as normal weight or overweight, while individuals with anorexia nervosa are severely underweight [5]. Sequelae of the disorder due to purging can be fatal and include esophageal tears, gastric rupture, and cardiac arrhythmias [1]. Up to 3% of females and 1% of males will experience BN within their lifetimes [3].

BED is the most common eating disorder [6]. In contrast to bulimia nervosa, BED involves an individual experiencing recurrent episodes of binge eating without subsequent actions to compensate for overeating [4]. The disorder, naturally, is often associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome due to binging and the subsequent high caloric intake without the compensatory measures central to AN and BN [7]. The prevalence of BED worldwide for 2018–2020 is between 0.6 and 1.8% in adult women and 0.3 and0.7% in adult men [8].

2. Current Neuromodulatory Options and Their Target Networks/Nodes

2.1. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation

Non-invasive brain stimulation refers to methods of modulating brain and network activity via non-surgical procedures. These methods commonly include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). In the context of eating disorders, both methods have been thoroughly studied in vivo, with rTMS representing a larger share of the studies. Currently, neuromodulatory techniques are neither considered first-line nor approved therapies for eating disorders [9][39]. This is true for both rTMS and tDCS, the two most commonly investigated non-invasive methods discussed in this research; however, there is substantial evidence to suggest these methods are both safe and beneficial in the treatment of AN, BN, and BED [10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. In the articles discussed below, the application of rTMS (summarized in Table 1) and tDCS (summarized in Table 2) often followed a prolonged eating disorder course, many times refractory to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, which is suggestive of neuromodulation being indicated in cases of resistant eating disorders. As previously discussed, there are numerous aberrant brain networks involved in disordered eating. Most of the studies of non-invasive brain stimulation have targeted the dlPFC, and several have targeted the dmPFC [19][20][32,49]. Likewise, the dmPFC has been shown to have differential activity in AN, BN, and BED when compared to healthy controls [21][50]. As mentioned prior, the PFC and its partitions play a role in both executive inhibitory control and reward processing, the dysfunction of which is contributory to all of the eating disorders discussed here [22][51]. Naturally, the targeting of these regions aims to override the aberrancy of the various frontal–striatal networks. To date, no other targets have been investigated, but this is certainly a potential area of study in this nascent field.Table 1.

TMS studies included, sorted by disease type followed by year of publication.

| Disorder | First Author, Year | Country of Study | Sample Size | TMS Pattern | Number of Sessions | TMS Target | Duration of ED | Initial BMI | BMI Outcome | Disease Severity Outcome | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Study | Sample Size | tDCS Parameters | Number of Sessions | Intervention Target | Duration of ED | Initial BMI | BMI Outcome | Disease Severity Outcome | |||||||||||||

| AN with comorbid MDD | Kamolz, 2008 [23][52] | Germany | 1 | 100 cycles of 10 Hz for 2 s on/10 s off | 3 series for 26 total sessions | dlPFC | |||||||||||||||

| AN | Khedr, 2014 [37] | 4 years | [66] | 12.4 kg/m | 2 | Egypt | Increased to 16 kg/m | 2 | 7 | Initial HAMD value of 28 decreased to 11. | |||||||||||

| Anodal 2 mA for 25 min with 15 s ramp in and ramp out | 10 sessions | Left dlPFC along parasagittal line | Mean of 3.4 years | Mean 14.85 kg/m | 2 | (12–17 kg/m | 2 | ) | N/A | AN (restricting and binge–purge type) | Van den Eynde, 2013 [24][53] | UK | 10 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 1 session | Left dlPFC | 10 (3–30) years | 15.7 kg/m2 (13.8–17.8 kg/m2) | N/A | Sensations of “feeling fat” and “feeling full” decreased along with “urge to exercise.” Reduced feelings of anxiety. |

|

| Significant decreases in body dissatisfaction, interpersonal distrust, interoceptive awareness, and ineffectiveness scores of the EDI. | Significant improvement in BDI from 22.4 to 13.3. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AN | Costanzo, 2018 [15][45] | Italy | 23 | 1 mA anodal stimulation | 18 sessions | Anode over left dlPFC and cathode over right dlPFC | N/A | Mean 14.7 kg/m2 for tDCS group, 15.5 kg/m2 for sham group. | tDCS with “treatment as usual” resulted in significant improvements in BMI. No significant change in family-based therapy with “treatment as usual” group. | Significant improvement in multiple eating disorder subscales, but not significant between groups. | AN (restrictive with comorbid MDD; binge–purge) | McClelland, 2013 [25][54] | UK | 2 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 20 sessions; 19 sessions | Left dlPFC | 12 years; 35 years | 15.7 kg/m2, 16.4 kg/m2 | BMI decreased at 1 month follow-up in both patients (average decrease of ~0.7 kg/m2) | EDE and DASS scores decreased in both patients. Patient 1 reported increase in purging frequency. Patient 2 reported decreased purging and laxative use. |

| AN (binge–purge subtype) or BN | Dunlop, 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AN | Phillipou, 2019 [38][67] | Australia | 20 | Anodal stimulation for 20 min at 2 mA | 10 sessions | Anode over left inferior parietal lobe | Currently underway | [26][55] | Canada | 28 (16 responders) | 60 cycles of 10 Hz, 5 s on/10 s off | 20 sessions; 30 for responders with residual symptoms | Bilateral dmPFC | 14.75 years | |||||||

| AN | Mares, 2020 [39][ | 19.03 kg/m | 2 | N/A | 68] | No significant difference at baseline between responders and non-responders. | Among responders, binge and purge frequency decreased. No change in non-responders. | ||||||||||||||

| Czechia | 1 | 30 min of 2 mA anodal stimulation | 7 sessions | Left dlPFC anode with cathode over the right orbitofrontal region | 11 years | 17.4 kg/m | 2 | N/A | During tDCS, the patient developed hyperglycemia and, subsequently, diabetes mellitus. | AN | McClelland, 2016 [27][56] | UK | 60 (49 completed study) | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 1 session | Left dlPFC | 9.05 years for TMS group, 11.27 years for sham | ||||

| AN | Ursumando, 2023 [40][69] | 16.73 kg/m | 2 | Italy | for TMS group, 16.38 kg/m | 80 | 20 min of 1 mA stimulation | 2 | 1 session for sham | N/A | Single session of TMS resulted in lower core AN symptoms of feeling full, urge to restrict, and feeling fat. | ||||||||||

| F3 (anode) and F4 (cathode) of dlPFC | Currently underway | AN | |||||||||||||||||||

rTMS for BN

Second to AN, BN is the most studied eating disorder with respect to rTMS. In regard to the binge–purge behavior characteristic of BN, RCTs exploring rTMS for the treatment of BN were more limited and have conflicting reports of efficacy. Van den Eynde et al. performed a randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind study with 38 patients to investigate rTMS to the left dlPFC [12][42], finding self-reported food cravings and the frequency of binging episodes to be significantly decreased. However, both Walpoth et al. [33][62] and Gay et al. [36][65] conducted RCTs with 14 and 47 participants, respectively. Neither of these two groups were able to find significant differences in binge–purge behaviors between the treatment and sham groups. When examining psychometrics, the results were equally variable. Walpoth et al. [33][62] were not able to find significant improvements in the measures of depression or obsessive-compulsive behavior between groups. Conversely, Guillaume et al. investigated the effects of the rTMS treatment on decision making and impulse control [57][86], finding a statistically significant improvement in impulse control, as well as decision making when assessed using the Iowa gambling task. There also exist studies of smaller sample sizes that explore rTMS in BN, finding more consistent therapeutic results. In another study by the Van den Eynde group—a case series of rTMS applied to the left dlPFC in seven left-handed patients [34][63]—the group found decreases in BN core symptomatology with variable changes in mood depending on hand dominance. Hausmann and colleagues’ case study presented a patient with BN and comorbid MDD who underwent left dlPFC rTMS [32][61], resulting in the complete remission of binging behavior and a 50% decrease in depressive symptoms. Targeting the bilateral dmPFC, Downar and colleagues reported the case of a patient with BN and comorbid MDD [35][64]. The patient experienced a complete remission of binging–purging behaviors up until their 2-month follow up. In a subsequent study by the same group, Dunlop and colleagues reported a case series involving 28 patients [26][55], in which 16 of the 28 patients experienced a >50% reduction in weekly binges at their 4-week follow-ups. fMRI imaging was obtained before and after treatment, showing lower baseline functional connectivity between the dmPFC, and the structures of the lateral OFC and right posterior insula. Responders additionally exhibited lower baseline functional connectivity between the dACC, the right posterior insula, and the right hippocampus, which is consistent with the aforementioned dysfunctional reward pathways. Dunlop and colleagues also identified lower baseline functional connectivity between the dACC and the ventral striatum as well as the anterior insula in responders and found that such connectivity increased with treatment. Conversely, non-responders were found to have high baseline frontostriatal functional connectivity, which was decreased by rTMS and correlated to a worsening of symptoms [26][55]. Despite promising case studies and case series, multiple sham-controlled, double-blind RCTs failed to observe any difference between rTMS and a sham for patients with BN [33][36][62,65]. As such, further RCTs would prove beneficial in characterizing the target, the parameters, and the patient selection that are optimal for rTMS to be effective in BN studies.rTMS for BED

There are few studies addressing rTMS for BED. There is a clear need for more studies to define the role of non-invasive brain stimulation in the treatment of this disorder. Sciortino and colleagues published one of the few studies on the topic, presenting two patients with BED and comorbid treatment-resistant bipolar disorder type II who were treated with iTBS to the left dlPFC [13][43]. Both patients experienced complete remission in their binge eating symptoms that lasted until their 12-week follow-up visits with only a minor improvement in their depressive symptoms; manic symptoms were absent throughout.3.1.2. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

tDCS is another form of non-invasive brain stimulation that has been studied in a variety of psychiatric and neurologic disorders, including MDD [58][87], schizophrenia [59][88], substance use disorder [60][89], OCD [61][90], GAD [62][91], and eating disorders. Although there are currently no FDA-approved protocols for tDCS, it has shown promise in numerous clinical studies [63][92]. In tDCS, electrodes are placed on the scalp, and a weak current is passed through the brain between the two electrodes. Anodal stimulation is thought to be excitatory, while cathodal stimulation is thought to be inhibitory [64][93]. Most tDCS protocols deliver a current of 1–2 mA in 10–20 min treatment sessions, and patients undergo 10–20 treatments [63][92].tDCS for AN

There have been several studies investigating the effects of tDCS on AN, as well as a few ongoing RCTs that are not yet concluded. The largest of the completed studies is a single-blind trial consisting of 23 patients by Costanzo and colleagues. They applied tDCS to the left dlPFC and compared the effects to those of standard therapy [15][45]. They identified increases in BMI in the tDCS group only at a one-month follow-up. Khedr and colleagues performed an open-label, single-arm study consisting of seven patients who received tDCS to the left dlPFC [37][66]. In the study, the group found a statistically significant improvement in the core AN and depressive symptomatology at the 1-month follow-up visits. It is worth mentioning a case report published by Mares et al. [39][68] whereby a patient with comorbid PTSD was discovered to have type I diabetes mellitus (DM) during tDCS to the left dlPFC. It is unclear whether the onset of the patient’s DM was a direct consequence of stimulation. The currently ongoing studies include a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial of tDCS to the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and is being conducted by Phillipou and colleagues [38][67] and Ursumando et al. [40][69]. Phillipou et al. chose the IPL given the decreased functional connectivity between midbrain structures and the IPL that they previously observed in patients with AN [65][94]. Ursumando et al. [40][69] are conducting a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial of tDCS to the left dlPFC in the pediatric population.tDCS for BN

The literature surrounding the tDCS of BN is relatively sparse, with only one primary research article having been identified. That study, conducted by Kekic and colleagues, consisted of a double-blind, sham-controlled proof-of-principle trial utilizing tDCS applied to the right and left dlPFC for 39 patients with BN [16][46]. In their study, patients received three sessions of tDCS—anode right/cathode left, cathode right/anode right, and sham—in a counterbalanced, randomized order. A variety of binge eating and psychologic tests were performed after each session and at 24 h. Binge eating symptoms and the ability to value delayed rewards improved with both the right and left anodal montages. Interestingly, mood symptoms improved only with the right anodal montage. Such results signify the importance of further exploration of tDCS’s role in the treatment of BN [16][46].tDCS for BED

The literature regarding tDCS for the treatment of BED is more numerous. Overall, the results have been consistently promising. In a case series involving 30 patients with BED, Burgess and colleagues performed 2 mA tDCS to the dlPFC or a sham in a counterbalanced study paradigm [41][70]. They found tDCS to be associated with decreased food cravings and intake, as well as binge eating desire (with a larger effect size in the male cohort). In a double-blind RCT, Max et al. investigated the effect of tDCS to the dlPFC in a counterbalanced order in 31 patients [43][72]. They performed a food-modified antisaccade learning task and found that the 2 mA tDCS protocol decreased latencies and binge eating episodes, whereas the 1 mA tDCS increased latencies and had no effect on binge eating episodes. These results suggest that tDCS monotherapy at 2 mA may improve eating disorder symptoms, possibly as a result of improved inhibition functions regarding rewarding food stimuli, while 1 mA stimulation may have a detrimental effect. Additionally, there is considerable interest in studying tDCS as an adjunct therapy for BED. In a phase-II sham-controlled, double-blind randomized control trial, Giel and colleagues assessed the effect of combining inhibitory control training with right-anodal 2 mA tDCS to the dlPFC vs. a sham in 41 patients with BED [8]. They found a significant reduction in binge eating frequency in both the treatment and the sham groups at 4 weeks and 12 weeks, with a statistically significant difference between the treatment and sham groups only at the 12-week timepoint. Gordon et al. are currently conducting a sham-controlled crossover RCT that examines the effect of a combined approach bias modification (ABM) training co-administered with either anodal tDCS to the right dlPFC or a sham in 66 patients with BED [42][71]. ABM is a learning method that reinforces avoidance behavior in response to food cues. The authors of the study have thus far published on the patients’ experience with ABM, and overall, patients have found ABM to be a worthwhile activity [66][95]. Full results from the work by the group are pending. The TANDEM trial by Flynn and colleagues is another exciting single-blind, sham-controlled randomized trial that will look at self-administered at-home anodal tDCS to the right dlPFC with concurrent ABM training [45][74].2.1.3. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

ECT is the oldest form of non-invasive brain stimulation that has shown some efficacy in a variety of psychiatric disorders, including treatment-refractory depression [67][96], bipolar disorder [68][97], and schizophrenia [69][98]. ECT induces a brief, generalized tonic-clonic seizure through an external current [70][99]. It is generally a well-tolerated procedure with a low risk profile, and its use is mostly restricted to the acute inpatient treatment of severe, refractory psychiatric disorders (e.g., mania, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and suicidality) [68][71][97,100]. Despite its well-established use in multiple psychiatric conditions, there have been few studies investigating the efficacy of ECT in the context of eating disorders. Given its restricted use to acute psychiatric crises and the need for general anesthesia, ECT is unlikely to find significant use in the outpatient management of disordered eating when compared to other non-invasive brain stimulation methods.2.2. Invasive Neuromodulation

As opposed to non-invasive brain stimulation, invasive neuromodulation involves surgical intervention and the placement of deeper-reaching stimulation devices. While these methods include both deep brain stimulation (DBS) and Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS), the vast majority of invasive neuromodulation for eating disorders involve DBS. The curation of potential targets for DBS largely stems from attempts to treat comorbid conditions, namely MDD [72][101] and OCD [73][102]. Today, studies primarily target the subcallosal cingulate (SCC) target [72][74][101,103] and the nucleus accumbens (Nacc) [75][76][77][104,105,106], the exploration of which have been largely led by Canadian and Chinese groups, respectively. Alternatively, Israël et al. reported one of the earliest cases of SCC DBS in a 52-year-old woman with comorbid depression [72][101] as the SCC is a target that was previously explored for the treatment of depression as well as OCD. Furthermore, studies of OCD patients who underwent Nacc DBS also reported improvement in anorexia symptoms [73][102].2.2.1. Deep Brain Stimulation

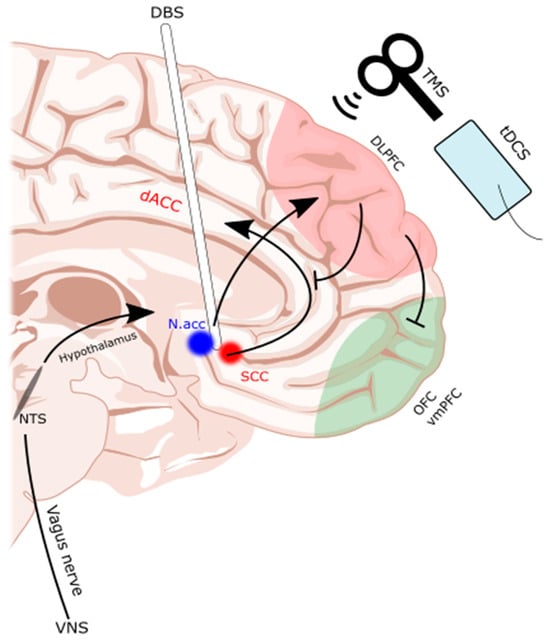

DBS involves the implantation of an electrode into a deep brain structure [75][104]. Given this degree of invasiveness, DBS is generally an escalatory treatment option, usually reserved for those that are refractory to less invasive methods [74][75][78][103,104,107]. The Nacc and subcallosal cingulate (SCC) are the most common targets for DBS (Figure 1). The evidence is largely limited to a handful of case series and reports, which are summarized in Table 3. Many studies argued that DBS is warranted if patients are in a life-threatening situation due to a medically refractory disease [75][104] with no other reasonable treatment options, as the potential benefits would then outweigh the risks of surgery.

Figure 1. Subcallosal cingulate and nucleus accumbens as common DBS targets. TMS, tDCS, and DBS interventions are illustrated on a midline sagittal brain with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)/ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) of the frontostriatal networks highlighted. Additionally, the reward pathways of the deep brain are highlighted as they were targeted by the DBS electrode. dACC: dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. DBS: deep brain stimulation. Nacc: nucleus accumbens. NTS: nucleus tractus solitarius. SCC: subcallosal cingulate. tDCS: transcranial direct current stimulation. TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation. VNS: vagal nerve stimulator. Illustration based on brain atlas by Schaltenbrand and Wahren, 1977 [79][108].

Table 3.

Summary of included DBS cases, arranged by chronological order of study dates.

| First Author, Year | Country of Study | Sample Size | Intervention Target | Stimulation Parameters | Disorder | Inclusion Criteria | BMI Criteria | BMI Outcome | Disease Severity Outcome | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israël, 2010 [72][101] | Canada | 1 | Bilateral SCC | Unilateral stimulation on right side at 130 Hz, 5 mA for 2 min on, 1 min off | Restrictive AN | N/A. Patient has a disease duration of 35 years | N/A | Stable BMI at 2 years (19.1) | EAT-26 was 1.04 and 1 at 2 and 3 years. Low EDE score at 3 years “comparable to normal population”. No QoL score. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Barbier, 2011 [80][109] | Belgium | 1 | Bilateral ALIC, BNST | N/A | AN with comorbid OCD | N/A. Patient has a disease duration of 24 years | N/A | From an initial BMI of 13.1 kg/m2, BMI increased to 13.7 kg/m2 and 23.0 kg/m2 at 2-week and 3 month follow-up, respectively | The patient exhibited reduction in YBOCS, EDE, EDI, food phobia survey, MADRS, and an increase in global function scores. | |||||||||||||||||

| Lipsman, 2013 [74][103] | Canada | 6 | Bilateral SCC | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz and 5–7 volts with a pulse width of 90 μs |

Restricting or binge–purge AN | Inclusion criteria: >2 years if increasingly medically unstable >3 years if relentless unresponsive >10 years if stable Actual: 4–37 years duration |

≥13 kg/m2 | 50% (3 of 6) patients had higher BMI at 9 months than baseline | YBC-EDS (preoccupations) changed from 23.7 preoperation to 17.7 at 6 months. YBC-EDS (rituals) changed from 29.3 to 19.0. Decreases in HAMD, BDI, YBOCS, and BAI. QoL score increased in those who gained weight. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Lipsman, 2017 [81][110] | Canada | 16 | Bilateral SCC | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz and 5–7 volts with a pulse width of 90 μs |

Restricting or binge–purge AN | Inclusion criteria: >2 years if increasingly medically unstable >3 years if relentless unresponsive >10 years if stable Actual: 4–37 years duration |

≥13 kg/m2 | BMI improved from 13.83 kg/m2 at baseline to 17.34 kg/m2 | Significant improvement in HAMD, BAI, and DERS at 12-month follow-up. No QoL measures reported. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Wu, 2013 [76][105] | China | 4 | Bilateral Nacc | N/A | AN (subtype not specified) | >12 months duration of illness (range: 13–28 months) | None specified (range: 10–13.3) | Average 65% increase in BMI at 38-month follow-up | No AN-specific assessments reported. YBOCS and HAMA scores were reduced on average. No QoL measures were reported. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Choudhary, 2017 | [ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BN | 28][57] | Kekic, 2017 [16India | ][461 | ] | UK1000 pulses of 10 Hz stimulation | 21 sessions | 39 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Wang, 2013 [77][106 | 20 min of 2 mA with 10 s ramp on/off | ] | China | 2 (6 more underwent RF ablation) | 3 sessions | Bilateral NaccLeft dlPFC | 9 years | Bilateral stimulation at 135–185 Hz and 2.5 to 3.8 volts with a pulse width of 120–210 μs | AN | >2 years duration of illness10.94 kg/m2 | F4 (anode) and F3 (cathode) of dlPFC in one group; F3 (anode) and F4 (cathode) of dlPFC in the other group | Not specified | Both DBS patients experienced increases in BMI from 13.1 kg/m2 to 18.0 kg/m2 and 12.9 kg/m2 to 20.8 kg/m2, respectively, at 1-year follow-up17.98 kg/m2 at end of 3-week treatment, 18.55 kg/m2 at 8-week follow-up | Laxative and diuretic abuse decreased significantly. | ||||||||||||

| Mean 9.25 years | Mean of 21.65 kg/m | 2 | N/A | No ED-specific scale. | QoL: SF-36 improved in physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, social functioning, and role-emotional 1 year post-operation. General health, vitality, and mental health were improved at 6 months and 1 year post-operation. | Both stimulatory groups exhibited decreased self-reported urge to binge eat and increased self-regulatory control. Anode right/cathode left stimulation reduced global MEDCQ-R compared to the other groups. |

Social functioning: SDSS scores improved. | AN (comorbid depression and anxiety) | Jaššová, 2018 [29][58] | Czech Republic | ||||||||||||||||

| BED | Burgess, 2016 [41 | 1 | ] | 10 Hz, 15 trains/day, 100 pulses/train, intertrain interval of 107 s | 10 sessions | [Left dlPFC | 1.5 years | 12.21 kg/m2 | 70]13.15 kg/m2 at discharge, 22.9 kg/m2 at 2-year follow-up | USANo change in Zung self-rating scale (score = 70). | ||||||||||||||||

| 30 | 20 min of 2 mA | 1 session | Anode on right dlPFC, cathode on left dlPFC | N/A | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blomstedt, 2017 [82][111] | Sweden | Mean of 36.1 kg/m | 1 | 2 | Bilateral medial forebrain bundle, followed by bilateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis | Bilateral medial forebrain bundle stimulation at 130 Hz and 2.8 to 3.0 volts with a pulse width of 60 μs Bilaterally bed nucleus stimulation at 130 Hz and 4.3 volts with a pulse width of 120 μs |

AN and comorbid MDD | N/A. Duration of disease not specified. Originated during childhood for this 60-year-old patient | N/A | BMI marginally increased at 12 months from 16.2 kg/m2 to 16.5 kg/m2N/A | under medial forebrain bundle stimulation. BMI marginally decreased from 14.5 kg/m2Significant fewer total calories consumed by the tDCS group. Additionally, mean decrease in consumption of preferred foods by 70.28 kcals. tDCS decreased cravings for desserts more than sham. No effect on binge frequency. |

to 14.3 kg/m2 under bed nucleus stimulation | Medial forebrain bundle stimulation improved MADRS, HAMA, and GAF scales, but worsened HAMD. Bed nucleus stimulation resulted in improvement in HAMD and GAF, with marginal improvement in MADRS, and worsening of HAMA. |

AN | Dalton, 2018 [30][59] | UK | ||||||||||

| BED | Gordon, 2019 [42 | 34 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 20 sessions | Left dlPFC | Average 14.07 years | Average 16.00 kg/m | 2 | Small but non-significant increases in BMI at end of stimulation and 4-month follow-up | Significant decreases in DASS global score, favoring TMS. | ||||||||||||||||

| Manuelli, 2019 | ][71] | UK | [66 | 2 mA with 10 s fade-out and fade-in | 836 sessions over 3 weeks | Anode on right dlPFC, cathode on left dlPFC | ] | Currently underway | [112] | Italy | 1 | Bilateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz and 4 volts with a pulse width of 60 μs | AN | N/A. Patient has a disease duration of 18 years | N/A | BMI steadily increased monthly from an initial 16.31 kg/m2 to 18.98 kg/m2 at 6 months | Consistent improvement in BUT subscores, except for “depersonalization”, which showed variable changes. BITE, EAT-26, and YBOCS scores also consistently improved. QoL: SF-36 showed consistent monthly improvement. |

AN | |||||||

| Liu, 2020 [75][104 | Dalton, 2020 (18-month follow-up from Dalton, 2018) [31][60] | UK | 30 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 20 sessions | Left dlPFC | Average 14.07 years | Average 16.00 kg/m2 | Non-significant increase in BMI at 18-month follow-up | |||||||||||||||||

| BED | ]Max, 2021 [43][72] | China | Higher rate of weight recovery in TMS group (46% vs. 9%). | Non-significant improvements in EDE-Q global in both groups and improvements in DASS-21 were maintained in both groups. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 31 | 20 min of 1 mA (n = 15) or 2 mA (n = 16) | 1 session | Anode over F4, cathode over left deltoid muscle | N/A | Mean 32.1 kg/m | 2 | in 1 mA group, mean 33.8 kg/m2 in 2 mA group | N/A | 2 mA group showed significantly fewer binge episodes with 1 mA group showing no changes. 2 mA group demonstrated improved food inhibition in UPPS. |

28 | Bilateral Nacc | Bilateral stimulation at 160–180 Hz and 2.5–4.0 V with a pulse width of 120–150 μs | AN | >3 year duration of illness, resistance to medical treatment for at least 3 months | Not specified | BMI significantly improved from baseline of 13.01 kg/m2 to 15.29 kg/m2 and 17.73 kg/m2 at 6-month and 2-year follow-ups, respectively | No ED-specific scale. Significant decreases in YBOCS, HAMA, and HAMD at 6 months and 2 years. Significant increase in MMSE at 6 months and 2 years. Social functioning: SDSS improved from 11.14 to 8.64 at 6 months and 4.22 at 2 years after surgery. No QoL measures reported. |

AN | Woodside, 2021 [11][41] | Canada | 19 | 10 Hz | 22.6 average (20–30) sessions | Bilateral dmPFC | N/A |

| BED | Giel, 2023 [ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arroteia, 2020 [84][113] | 44][73] | Luxembourg | 1 | Bilateral Nacc | Bilateral stimulation at 204 Hz and 4.5 to 5.5 mA with a pulse width of 350 μs | 16.4 kg/m | Bulimic AN | Not specified | Not specified. Patient’s BMI 12.8 kg/m22 (14.5–18.5 kg/m2) | Germany | 41 | 15 min of 2 mAAverage BMI declined to 16.3 kg/m2 at end of treatments | 46.9% increase in weight at 12-month follow-up. At 14 months, binge eating and purging frequency increased, which persisted until 19 months. DBS explanted at 24 months due to infection | No ED-specific scale. No QoL or social functioning outcomes. Significant improvements in shape concerns and weight concerns in EDE. Additionally, improvement in BAI and BDI. |

||||||||||||

| 6 sessions | Anode over F4, cathode over left deltoid muscle | Patient subjectively reported no change in behavior (anorexia/bulimia) but reported improvements in mood and energy. | BN with comorbid MDD | Hausmann, 2004 [32][61] | Austria | 1 | 10 trains of 10 s 20 Hz pulses with a train interval of 60 s | 10 sessions, twice daily for 5 days | Left dlPFC | 9 years | 18 kg/m2 | N/A | ||||||||||||||

| Villalba Martínez, 2020 [85][114] | Spain | 8 | Bilateral Nacc or SCC | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz with a pulse width of 90 µs Amplitude started at 3.5 mA and increased per patient tolerance | Absence of binge–purge behavior following stimulation treatment. | AN | HAMD decreased 50%. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Age of 18–60 years, >10 years duration of illness, and refractory to treatment (no response to ≥3 voluntary intensive treatments or clinical deterioration and rejection of further treatment with ≥2 involuntary hospital for nutritional rehabilitation) | ≥13 kg/m | 2 | . One patient presented with a lower BMI and received preoperative admission for optimization of BMI | No change in mean BMI at 6 months. However, when adjusting for need for preoperative optimization, there was revealed to be a ≥10% increase in BMI in 5 patients | Mean increases in SF-36 scores (QoL measure). | BN | Walpoth, 2008 [33][62] | Austria | 14 | 10 trains of 10 s 20 Hz pulses with a train interval of 60 s | 15 sessions | Left dlPFC | Average 8.4 years for TMS group, average 8.0 years for sham group. | |||||||||||||

| De Vloo, 2021 [86][ | Average 19.6 kg/m | 2 | in TMS group, average 19.7 kg/m | 2 | in sham group. | N/A | Significant improvement in BDI, frequency of binging, and YBOCS at end of treatment, but no significant change between groups. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 115] | Canada | 15 | Bilateral SCC | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz and 5.0–7.0 V with a pulse width of 90 µs | Restricting or binge–purge AN | Inclusion criteria: >2 years if increasingly medically unstable >3 years if relentless unresponsive >10 years if stable |

BN | Van den Eynde, 2010 [12][42] | UK | 38 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 1 session | Left dlPFC | Median 5–10 years in TMS group, median 0–5 years in sham group. | Average 25.8 kg/m2 in TMS group, average 25.0 kg/m2 in sham group. | N/A | Significant decrease in urge-to-eat VAS in the TMS group. No significant changes in hunger, urge to binge, mood, tension, or FCQ-S between groups. |

|||||||||

| BN | Van den Eynde, 2012 [34][63] | UK | 7 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 1 session | Left dlPFC | Median 0–5 years in the left-handed group, median 5–10 years in the right-handed group. | Average 22.9 kg/m2 in left-handed group, average 28.5 kg/m2 in right-handed group. | N/A | No significant differences in urge to eat, mood, tension, hunger, urge to binge eat, and FCQ-S between left- and right-handed groups. Mood differed significantly between groups, with the left-handed group experiencing a worsening in mood and the right-handed group experiencing an improvement in mood. |

||||||||||||||||

| BN with comorbid MDD | Downar, 2012 [35][64] | Canada | 1 | 60 trains of 10 Hz for 5 s on/10 s off | 20 sessions | Bilateral dmPFC | 28 years | 20.3 kg/m2 | N/A | Initial HAMD of 26 and 28 on the BDI; decreased to 0 at the end of treatment and 7 after 11 sessions, respectively. Binge–purge behavior disappeared completely after session 11 (originally twice-daily 5 h binges with subsequent purging). Single binge–purge episodes on days 65, 70, and 71 post-treatment. |

||||||||||||||||

| BN | Gay, 2016 [36][65] | France | 47 | 20 cycles of 10 Hz for 5 s on/55 s off | 10 sessions | Left dlPFC | Average 8.0 years in TMS group, average 10.5 years in sham group. | N/A | N/A | No significant changes in binging, purging, craving, MADRS, or duration of binging. | ||||||||||||||||

| BED with comorbid bipolar II disorder | Sciortino, 2021 [13][43] | Italy | 2 | 30 Hz bursts at 5 Hz intervals; 2 s on/12.3 s off; 600 pulses per session | 18 sessions across 3 weeks | Left dlPFC | 32 years, 10 years | N/A | Weight reduction of 4 kg and 2 kg at 12-week follow-up. | HAMD and MADRS improved marginally in both patients. YMRS remained at 0 throughout for both. Complete remission of binging episodes at the end of 2 weeks of treatment. |

||||||||||||||||

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress scale; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination; FCQ-S, Food Craving Questionnaire-State; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Table 2.

tDCS studies included, sorted by disease type followed by year of publication.

| Disorder | First Author, Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | ||||||||||

| Mean 31.9 kg/m | ||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||

| for tDCS + FRIC group, 36.0 kg/m | ||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||

| for sham + FRIC group. | ||||||||||

| Both groups experienced significant reduction in BMI | ||||||||||

| Both groups experienced significant improvement in EDE and QoL scales. | Greater reduction in binge eating frequency in the tDCS + FRIC group vs. sham + FRIC group. | |||||||||

| BED | Flynn, 2023 [45][74] | UK | 80 | 2 mA | 10 sessions over 2–3 weeks | Bilateral dlPFC | Currently underway | |||

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; EDI, Eating Disorders Inventory; FRIC; Food-related inhibitory control training; MEDCQ-R, Mizes Eating Disorder Cognition Questionnaire-Revised; UPPS, UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale.

2.1.1. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

rTMS is non-invasive form of neuromodulation that has demonstrated efficacy in numerous neurologic and psychiatric disorders and is FDA-approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), migraine with aura, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), smoking cessation, and anxiety with comorbid MDD [46][75]. In rTMS, local magnetic fields are generated by passing a current through several coils in different orientations around the patient’s head. These magnetic fields can be targeted to regions of interest and induce electrical currents in the brain to modulate neural networks of interest [47][76]. It is a well-tolerated modality, associated only with simulation site discomfort and headache with rarely reported suicidal ideation and the worsening of psychiatric symptomatology [48][77]. There are essentially three protocols with which rTMS therapy is delivered: low frequency, high frequency, and theta-burst frequencies. High-frequency stimulation (5–20 Hz) increases cortical excitability and is thought to act through long-term potentiation (LTP), while low-frequency (1 Hz) stimulation is thought to decrease cortical excitability and act instead through long-term depression (LTD) [49][50][78,79]. More recently, theta-burst stimulation (TBS) (three pulses of 50 Hz repeated at a 5 Hz frequency) has emerged as a mimic of endogenous brain rhythms [51][80]. It can be delivered intermittently (iTBS) or continuously (cTBS), whereby iTBS produces excitatory effects, and cTBS produces inhibitory effects [52][81]. One classical limitation of rTMS is the superficial depth of its effect. To attempt to address this shortcoming, deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS) was developed as a means of generating magnetic fields that are capable of reaching and influencing deeper brain structures (such as the hippocampus and nucleus accumbens) than that of standard rTMS [53][82].rTMS for AN

Of all the eating disorders, TMS for AN is the most well-established, with the most common target being the dlPFC [54][55][83,84]. The most significant RCT to date is the TIARA study, a double-blind clinical trial of rTMS to the left dlPFC by Dalton and colleagues [30][31][59,60]. Thirty-four participants with an illness duration of 3 years or more were randomized to receive either rTMS or a sham [30][59]. In the TIARA study, not only did participants’ BMI improve, but so did eating disorder symptoms (i.e., feelings of fullness, fatness, and anxiety). Additionally, mood symptoms and quality of life (QoL) were found to be moderately improved. rTMS also demonstrates long-term benefits as the rTMS group demonstrated continued improvement in BMI, mood, and core AN symptomatology at 18 months. In an adjunct study of the same participants, the authors found rTMS resulted in a significant decrease in restrictive, self-controlled food choice behavior [31][60]. The authors also assessed cerebral blood flow (CBF) via arterial spin label fMRI [56][85]. Interestingly, while the dlPFC is a critical region in the frontal–striatal regions, the authors found a significant decrease in amygdala CBF in the rTMS group relative to the sham group, with amygdala CBF inversely correlating to BMI. The change in amygdala CBF was proposed to be the result of indirect projections from the dlPFC and suggestive of a reduced fear response regarding weight gain| Actual: 4–37 years duration | |||||||||

| ≥13 kg/m | |||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| Mean BMI increased significantly from 14.kg/m | |||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| to 17.5 kg/m | |||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| and 16.3 kg/m | |||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| at 1- and 3-year follow-ups, respectively | |||||||||

| Significant improvements in YBOCS, YBC-EDS, HAMD, BDI, and BAI. | No improvement in QoL. | ||||||||

| Scaife, 2022 [87][116] | UK | 7 | Bilateral Nacc | Bilateral stimulation at 130 Hz and 3.5 to 4.5 volts | AN | >7 years duration of illness. Mean of 21 years (range 12–40 years) | BMI 13–16 kg/m2 | No significant change in BMI (15.2 kg/m2 to 15.3 kg/m2) at 12 months. 3/7 patients responded (defined as >35% increase in EDE) |

At 12 months, mean EDE reduced from 4.2 to 3.4, (19.0% reduction), mean YBC-EDS reduced from 21.9 to 19.7 (10.0% reduction), and mean CIA reduced from 39.0 to 31.1 (20.3% reduction). HAMD and HAMA also decreased with an increase in SHAPS. QoL: WHO-QoL-Psych improved from 7.9 to 9.4 (18.9% increase). |

| Shivacharan, 2022 [78][107] | USA | 2 | Bilateral Nacc | Responsive pulses delivered bilaterally at 125 Hz in two 5 s bursts; charge density of 0.5 μC cm−2 | BED and severe obesity | Failure of either 6 months of pharmacotherapy, 6 months of behavioral therapy, or gastric bypass therapy | BMI 45 to 60 | BMI loss of −2.2 kg/m2 (−4.5%) in Subject 1, −2.9 kg/m2 (−5.8%) in Subject 2 at 6-month follow-up | Reduced loss-of-control eating frequency (Subject 1: 80% decrease; Subject 2: 87% decrease). No QoL or social functioning scales reported. |

ALIC, anterior limbs of the internal capsule; AN, anorexia nervosa; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BED, binge eating disorder; BITE, Bulimic Investigation Test Edinburgh; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; BUT, Body Uneasiness Test; DERS, Dysfunction in Emotional Regulation Scale; EAT-26, Eating Attitudes Test, 26-item; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination; GAF, Global Assessment of Function scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; Nacc, nucleus accumbens; SCC, subcallosal cingulate; SHAPS, Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale; SF-36, Short-form Health Survey; WHO-QoL-Psych, World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Assessment; YBC-EDS, Yale–Brown–Cornell Eating Disorders Scale; YBOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

Most studies defined surgical candidacy through a combination of severity and duration, although the threshold for intervention varied widely between studies. Generally, there should be a balance between allowing adequate time for natural history and/or response to medications, and the enabling treatment for patients who remain medically unstable with just non-surgical treatment alone. Earlier studies by Wu et al. [76][105] and Wang et al. [77][106], on the other hand, required disease durations of 1 to 2 years prior to the implantation of DBS electrodes.

Investigating the SCC, Lipsman et al. reported their experience with DBS implanted into the SCC for AN, with three out of six participants achieving an increase in BMI from the baseline at a nine-month follow-up [74][81][103,110]. For the initial three months post-surgery, there was a reported decrease in BMI, which the authors attributed to a regression to the baseline, as these patients all underwent a period of inpatient treatment for preoperative optimization prior to DBS implantation. This was followed by a gradual increase in weight that was sustained for more than nine months post-DBS implantation. A separate study by the same group followed 16 patients under the same protocol with a follow-up after up to one year. Again, Lipsman et al. found that patients who underwent bilateral SCC DBS experienced significant increases in BMI and significant improvements in various psychometric measures (full battery of measures in Table 3) [81][110]. Finally, recruiting from the patients in these previous studies, the group was able to follow 15 patients over the course of 3 years. Once again, the group was able to demonstrate an increase in the mean BMI (from 14.0 kg/m2 to 16.3 kg/m2), although the mean monthly binging/purging frequency was unchanged compared to the baseline [86][115]. Importantly, with regard to non-primary measures, the mean QoL did not improve, but the employment rate increased.

Regarding the Nacc, evidence consistently reports improvements in BMI. Wu et al. contemporarily implanted bilateral DBS into the Nacc of four patients with refractory AN, a subcomponent of the ventral striatum and, as mentioned prior, a crucial part of the reward circuitry. Here, the team found significant increases in BMI [76][105]. Importantly, in comparison to Lipsman et al.’s study, Wu et al. reported on a patient population with a significantly shorter duration of disease (13 to 28 months, versus 4 to 37 years in the Lipsman et al. study [74][103]). It is possible the BMI increase could be the result of secondary pharmacotherapy, as these patients also received concurrent SSRIs and olanzapine. The same group, Liu et al., published results from a larger cohort in 2020, with similar DBS parameters, resulting in 12 out of 28 (43%) patients achieving a BMI of >18.5 kg/m2 at 2 years [75][104]. The group also discovered via post hoc analysis that the restrictive AN subtype responded better than the binge eating subtype. In a case series conducted by Wang et al. in 2013, the team recruited a combined cohort of six patients who underwent bilateral Nacc RF ablation and two patients who underwent bilateral Nacc-DBS; in both groups of patients, a significant BMI increase was observed by one year, as well as significant improvements in QoL, anxiety, OCD, and depression measures [77][106]. In the only study to report no improvement from DBS to the Nacc, the Oxford group of Scaife et al. (2022) implanted DBS electrodes in seven patients [87][116].

Martínez et al. examined both targets by implanting DBS electrodes in either the SCC or Nacc, depending upon comorbidities (affective or anxiety disorder, respectively), in eight patients with refractory AN [85][88][114,117]. For those without a predominant comorbidity, the binge–purge subtype of AN received DBS to the Nacc, and the restrictive subtype of AN received DBS to the SCC. At 6 months, five of the eight participants experienced a ≥10% increase in BMI compared to the baseline with significant improvements in QoL measures.

DBS targeting the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST)—a target typically studied in the context of OCD—is far less common, and results from published studies have been conflicting [82][83][111,112]. It is believed that the BNST forms a network with the lateral hypothalamus and Nacc—regions involved in feeding and reward processing [89][118]. Blomstedt et al. first reported on the case of a 60-year-old patient with AN and comorbid MDD who received medial forebrain bundle (MFB) stimulation followed by bed nucleus of the stria terminalis stimulation (BNSF). Under the MFB condition, the greatest improvements were seen in the MADRS, Hamilton Anxiety Index, and the Global Assessment of Function Scale. The patient, however, experienced blurred vision as a complication of MFB stimulation, and was re-operated on to implant BNSF DBS electrodes. Under her new condition, depression ratings improved, as did anxiety and global function ratings. However, under both conditions, BMI changes were marginal (<0.3 kg/m2) [82][111]. Two years later, Manuelli et al. published their experience with a 37-year-old female patient diagnosed with severe restricting-type AN. Bilateral DBS was applied to the BNST, resulting in an improvement in bulimic, body uneasiness, and QoL scores. Importantly, the patient’s BMI increased at nearly every monthly follow-up for the duration of the study (6 months) [83][112].

The current body of evidence suggests that the SCC and Nacc may be effective DBS targets in the treatment of AN. Conversely, the evidence for the targeting of the BNST and the treatment of BED is less convincing due to conflicting results and a lack of studies, respectively. Moreover, there is a notable lack of evidence regarding DBS in the treatment of BN. Additionally, it should be noted that while most studies reported significant weight restoration and improvement in ratings of comorbid symptoms (i.e., depression, OCD, and anxiety), QoL improvement is less certain. Most studies did not provide strict metrics for QoL, although it is worth noting that among those that did [74][77][87][88][103,106,116,117], all but De Vloo et al. found improvements in such measures [86][115]. In reference to their findings, De Vloo et al. suggested that an early post-operative placebo effect and expectation bias could contribute to more positive short-term results which diminish in the long term [86][115]. Importantly, there is no guarantee that weight recovery implies improvement from the underlying psychological cause of anorexia nervosa. Future investigations can aid in this research by including QoL measures in their battery of tests and surveys.