Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Xinwei Ming and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Titanium (Ti) and its alloys are widely recognized as preferred materials for bone implants due to their superior mechanical properties. However, their natural surface bio-inertness can hinder effective tissue integration. To address this challenge, micro-arc oxidation (MAO) has emerged as an innovative electrochemical surface modification technique. Its benefits range from operational simplicity and cost-effectiveness to environmental compatibility and scalability. Furthermore, the distinctive MAO process yields a porous topography that bestows versatile functionalities for biological applications, encompassing osteogenesis, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties.

- titanium (Ti)

- micro-arc oxidation

- surface modification

1. Introduction

The latest statistics show that by mid-century, the global population aged 65 or over is expected to more than double to a staggering 1.6 billion people [1]. An aging population means a larger population base of chronic diseases, and bone and joint diseases. In dentistry and orthopedics, implants, with titanium (Ti) and its alloys as the preferred choice among various materials, have become a common approach for treating conditions due to their exceptional biocompatibility and mechanical properties [2]. Despite the vast potential for Ti and its alloys, there are still limitations to surface bioactivity. They often exhibit biological inertness, limiting the close integration of implants with surrounding tissues. Furthermore, Ti alloys are susceptible to microorganisms, increasing the risk of postoperative infections, and threatening the prognosis of patients. To tackle these issues, apart from alloying [3][4][5][3,4,5], surface treatment proves to be an effective approach as well. Common methodologies encompass atmospheric plasma spraying [6], laser treatment [7], anodizing [8], micro-arc oxidation (MAO), and biomimetic deposition of apatite [9] or other biomaterials [10]. Among the various surface modifications available, MAO has garnered significant attention due to its simplicity of operation, cost-effectiveness, and applicability to complex devices. Through MAO, the surface of Ti-based implants can undergo alterations in microstructural features and chemical composition, rendering them more suitable for tissue adhesion and effectively reducing the risk of infections [11].

2. Applications

MAO coatings, particularly with specific functional additives, possess remarkable biological functionalities including bone promotion, antimicrobial properties, and anti-inflammatory effects. Though clinical applications of Ti-based implants with MAO-modified functional coatings are limited, animal experiments have validated several implants with such coatings (Table 13). Presently, surface modification techniques like sandblasting, acid etching, and anodization, along with the introduction of bioactive materials such as calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, and calcium nanoparticles, are widely employed to optimize implant surface microstructure and topography. These modifications primarily aim to enhance biocompatibility and promote osseointegration. For example, MAO techniques have been utilized to create rough and porous surfaces on dental implants and femoral stems, facilitating improved tissue bonding [12][119].Table 13.

Coatings contain different components with different biological functions and are validated in vitro and in vivo.

| Number | Biologic Function | Adding Substances | Technique | In Vitro | In Vivo | Conclusion/Remark | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell | Bacterium | Animal Parts | ||||||

| 1 | Osteogenesis | Ca, Sr | MAO | hBMSCs | Simultaneously incorporating Ca and Sr demonstrated superior promotion of hBMSC proliferation. | [13][97] | ||

| 2 | Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis | Zn | MAO | HUVECs and BMSCs | In the Zn2+ environment, angiogenesis and osteogenesis mutually promote each other. | [14][106] | ||

| 3 | Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis | Hydroxyapatite nanotubes (HNTs) | MAO | HUVECs and MC3T3-E1 cells | HNT specimens promote both angiogenesis and osteogenesis on cellular and molecular levels. | [15][101] | ||

| 4 | Osteogenesis | B | MAO, hydrothermal treatment, and heat treatment | SaOS-2 cells | Nanorods inhibit SaOS-2 cell activity, whereas nanoparticles promote it. | [16][143] | ||

| 5 | Osteogenesis | Hierarchical coatings | MAO, electrochemical reduction | BMSCs | Beagle dogs, the shaft of the canine femur | The hierarchical coatings show higher osteogenesis rates compared to the ordinary MAO group. | [17][113] | |

| 6 | Osteogenesis | HA, BMP-2 | MAO, dip coating | MC3T3-E1 cells | Beagle femur | The interface bonding strength between HA/BMP-2 coating and surrounding new bone tissue is higher than that of Ca/PMAO coating. | [18][109] | |

| 7 | Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis | Ca, P, BMP-2 | 3D printing, sandblasting etching, MAO, electrochemical deposition | BMSCs | New Zealand White Rabbit Skull | MAO-CaP-BMP-2 is superior to the MAO and MAO-CaP groups in new bone formation. | [19][117] | |

| 8 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ca, P | MAO | hFOBs | E. coli and S. aureus | Volcanic-crater-like and needle-like CaP structures form at 350 V and 450 V, respectively. The former exhibits superior antibacterial performance and biocompatibility. | [20][121] | |

| 9 | Bioactivity/Antibacterial | Ca, P | MAO, UV catalysis | HGFs | S. sanguinis | Photofunctionalization reduces hydrocarbons and enhances surface protein adsorption. | [21][125] | |

| 10 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Zn | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli | Incubation with salt solution converts Zn ions into zinc oxide, which helps with long-lasting antibacterial activity. | [22][134] | |

| 11 | Antibacterial/Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis | Sr, Zn | MAO | HUVECs, BMSC | MRSA and P. gingivalis | Rat femoral model | The surface osteogenesis of samples doped with Sr and Zn is superior to other groups. (No in vivo antibacterial test conducted.) | [23][104] |

| 12 | Antibacterial | Ag, Cu NPs | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | MRSA | Mouse femur ex vivo experiment | Ag and Cu ions synergistically kill bacteria, allowing a 10-fold reduction in Ag ion concentration with consistent antibacterial efficacy. | [24][124] |

| 13 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ag, Zn | 3D printing, MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | MRSA | Mouse femur ex vivo experiment | The synergistic effect of Ag and Zn reduces the concentration of Ag+ by 120 times. | [25][128] |

| 14 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ag, Zn | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | S. aureus | Ag and ZnO synergy enhances antibacterial performance and promotes CaP phase formation. | [26][129] | |

| 15 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ag, Zn | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | S. aureus | Ag and Zn ion release is above the antibacterial threshold yet well below cytotoxic levels. | [27][130] | |

| 16 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ag, Zn | MAO | S. aureus | Ag and Zn have good synergistic antibacterial effects. | [28][131] | ||

| 17 | Osteogenesis, Antibacterial | Cu, Zn | MAO | MG63 | E. coli, S. aureus, and MRSA | Orthogonal experiments explore electrolyte effects on coatings, with phytic acid supplying the P element. | [29][132] | |

| 18 | Skin-integration/Antibacterial | Cu, Zn | MAO | Fibroblasts (L-929) | S. aureus | The synergistic effect of Cu and Zn facilitates skin integration and antibacterial activity. | [30][133] | |

| 19 | Osteogenesis, Anti-tumor/Antibacterial | Se | MAO | BMSCs, cancerous osteoblasts | S. aureus and E. coli | Se doping enhances osteogenic, anti-tumor, and antibacterial properties. | [31][103] | |

| 20 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Mn | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli | Rabbit femur | The coating induces osteogenesis and promotes osseointegration. | [32][137] |

| 21 | Antibacterial | Bi | MAO | MG63 cells | A. actinomycetemcomitans, MRSA | Bismuth nitrate has excellent antibacterial activity compared to bismuth acetate, bismuth gallate, and silver nitrate. | [33][138] | |

| 22 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ce | MAO | BMSCs | P. gingivalis, S. aureus | Osteoporotic rat hind legs | Ce-TiO2 coating has excellent antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. | [34][139] |

| 23 | Antibacterial | I | MAO, HT, photocatalysis | BMSCs | S. aureus | Tibial Intramedullary Infection Model of Rats | Under NIR, the coating has good antibacterial and osteogenic properties. | [35][140] |

| 24 | Antibacterial | I | MAO, electrophoresis | BMSCs | S. aureus and E. coli | The rat osteomyelitis intramedullary nail model | Thirty days after implantation, excellent antimicrobial ability was verified. | [36][141] |

| 25 | Bioactivity/Antibacterial | B | MAO | ADSCs | S. aureus and P. aeruginosa | Add a small amount of sodium tetraborate to the Ca, P electrolyte system. | [37][142] | |

| 26 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | F | MAO | BMSCs | S. aureus and E. coli | Rabbit femur | Coatings with high F addition showed improved antibacterial and osteogenic abilities. | [38][144] |

| 27 | Antibacterial/Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis | Sr, Co, and F | MAO | BMSCs | S. aureus and E. coli | Rabbit femur | Sr, Co, and F co-doped coatings induce osteogenesis. | [39][145] |

| 28 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Mn, F | MAO | BMSCs | S. aureus | Mn and F co-doped coatings show excellent wear and corrosion resistance, along with strong antibacterial properties. | [40][146] | |

| 29 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Cu, BMP-2 | MAO, dip coating | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli, MRSA, Neurospora crassa, and Candida albicans | Mouse craniotomy model | The coating significantly promotes osseointegration. | [41][110] |

| 30 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Ag, HA | MAO, RF-MS | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli | This coating exhibits strong biological activity and antibacterial properties. | [42][111] | |

| 31 | Bioactivity/Antibacterial | Ag NPs, polylactic acid (PLA) | MAO, electrospinning | MC3T3-E1 cells | S. aureus | PLA ultrafine fibers produced by electrospinning can control the release of silver ions. | [43][149] | |

| 32 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | AgNPs, polydopamine | MAO, dip coating | MG63 cells | S. aureus | New Zealand rabbit subdermal implantation | This coating exhibits strong biological activity and antibacterial properties. | [44][122] |

| 33 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Polydopamine, cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-3, phospholipid | MAO, dip coating | BMSCs and OBs | S. aureus and E. coli | The coating exhibits good osteogenesis and antibacterial properties. | [45][147] | |

| 34 | Antibacterial | GO | MAO, EPD | S. aureus and E. coli | Achieves ~80% antibacterial activity against E. coli and 100% against S. aureus. | [46][151] | ||

| 35 | Antibacterial | rGO, Ag NPs | MAO | MC3T3-E1 cells | MRSA | The coating exhibits good osseogenesis and antibacterial properties. | [47][152] | |

| 36 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | HA, chitosan (CS) | MAO, dip coating | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli | Higher usage of CS results in decreased biological performance but improved antimicrobial performance. | [48][153] | |

| 37 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | HA, CS hydrogel containing ciprofloxacin | MAO, HT, chemical grafting | hBMSCs | S. aureus and E. coli | The coating exhibits good osseogenesis and antibacterial properties. | [49][154] | |

| 38 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | BMP-2/CS/HA | MAO, dip coating | MC3T3-E1 cells | E. coli | CS encapsulation sustains BMP-2 release with added antibacterial properties. | [50][115] | |

| 39 | Antibacterial | Vancomycin | MAO, dip coating | The rabbit osteomyelitis model (infection with MRSA) | In vivo studies demonstrate the potential of this coating to prevent MRSA infection. | [51][148] | ||

| 40 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | Vancomycin | MAO, dip coating, chemical grafting | BMSCs | S. aureus | Rat femur | Functional coatings prevent prosthesis infection and promote bone integration at the interface. | [52][155] |

| 41 | Antibacterial | Mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs), octenidine (OCT) | Electrophoretic-enhanced MAO | OBs | S. aureus and E. coli | The coating exhibits good osseogenesis and antibacterial properties. | [53][156] | |

| 42 | Bioactivity/Antibacterial | N, Bi | MAO, photocatalysis | HGFs | Streptococcus sanguinis and Actinomyces nasseri | The coating has bactericidal properties under visible light. | [54][123] | |

| 43 | Osteogenesis/Antibacterial | MoSe2, CS | MAO, electrospinning, photocatalysis | MC3T3-E1 cells | S. mutans | Rat tibia | Adding MoSe2 significantly enhances TiO2 coating photothermal and photodynamic capabilities. | [55][161] |

| 44 | Skin-integration/Antibacterial | β-FeOOH, Fe-TiO2 | MAO, HT, photocatalysis | Mouse fibroblasts (L-929) | S. aureus | Mouse skin infection model | The β-FeOOH/FeTiO2 heterojunction prevents bacterial infection under light irradiation. | [56][108] |

| 45 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | Ca, Si | MAO | SaOS-2 cells | The coating inhibits inflammation and induces M2 macrophage polarization. | [57][167] | ||

| 46 | Antibacterial/Immunoregulation | Cu | MAO | RAW 264.7 macrophages, SaOS-2 cells | S. aureus | Cu boosts macrophage-driven osteogenesis and antibacterial activity in biomaterials. | [58][168] | |

| 47 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | Zn | MAO | RAW264.7 macrophages, BMSCs | The coating shows good osteogenic and anti-inflammatory properties. | [59][169] | ||

| 48 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | Mg | MAO | RAW 264.7 macrophages | Mg acts as an anti-inflammatory agent, inhibiting inflammation and promoting osteogenesis. | [60][170] | ||

| 49 | Anti-inflammatory | Co | MAO | RAW 264.7 macrophages | Mouse air chamber model | Cobalt-loaded Ti exhibits immune-regulatory effects on macrophages. | [61][171] | |

| 50 | Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | Li | MAO | BMDMs, mouse embryonic cell line (C3H10T1/2), HUVEC | Mouse air-pouch model | Low Li doses effectively regulate immunity, and promote osteogenesis. | [62][102] | |

| 51 | Osteogenesis/Angiogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | HA | MAO, SHT | MC3T3-E1 cells, human umbilical vein fusion cells, RAW 264.7 cells | Rabbit femur | This coating promotes osteogenesis and angiogenesis, and induces M2 macrophage phenotype. | [63][172] | |

| 52 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | HA | MAO, SHT | MC3T3-E1 cells, endothelial cells, RAW 264.7 cells | Rabbit femur | Nanoparticle-shaped HA is beneficial for osteogenesis, angiogenesis, and immune regulation, whereas nanorod-shaped HA is the opposite. | [64][173] | |

| 53 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | SiO2, ZnPs | MAO, sol-gel | MC3T3-E1 cells | The coating shows good osteogenic and anti-inflammatory properties. | [65][175] | ||

| 54 | Osteogenesis/Anti-inflammatory | Sr, silk fibroin-based wogonin NPs | MAO, electrochemical deposition, LBL | RAW 264.7 cells, OBs | Osteoporotic rat femur | The coating shows good osteogenic and anti-inflammatory properties. | [66][176] | |

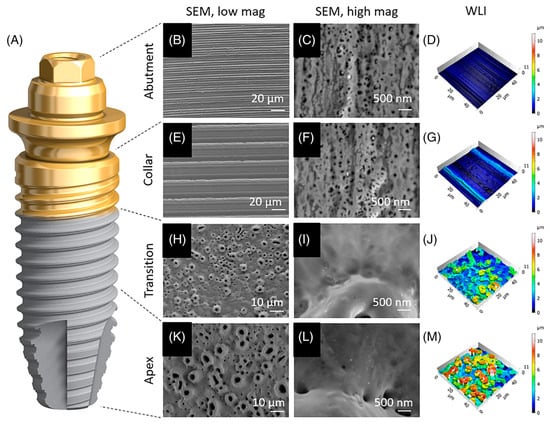

Figure 19. Implants with TiUltra surfaces [68][180]. (A) Microscopic analysis of the implant system’s four regions: abutment (B–D), implant collar (E–G), transition zone (H–J), and apex (K–M). This includes an overview (B,E,H,K), high-magnification scanning electron micrographs of each region (C,F,I,L), and 3D surface profile reconstructions using white-light interferometry (D,G,J,M).

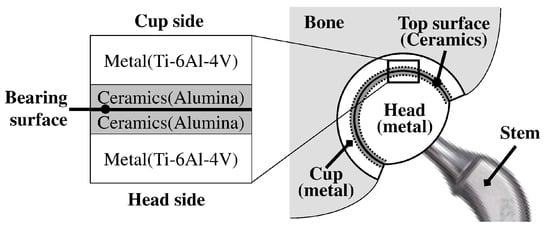

Figure 210.

The Bencox

TM stem is a collarless cementless bi-tapered rectangular Ti stem with an MAO-coated sandblasted surface [71].

stem is a collarless cementless bi-tapered rectangular Ti stem with an MAO-coated sandblasted surface [183].

3. Challenges

Although MAO coatings have undergone extensive research and led to the emergence of related products, there are still challenges and limitations in the production and application:-

In the coating manufacturing process, establishing the electrolyte composition and electrical parameters still necessitates multiple experiments. Defining the optimal parameters remains challenging. Minor losses of electrolytes during usage and the settling of particulate or colloidal electrolytes can also impact coating performance [75][76][44,54].

-

The impact of coating morphology on cell bioactivity remains inconclusive. While some studies suggest that moderate roughness aids in cell adhesion and proliferation, and porous surfaces facilitate cell osteogenic differentiation, there is still debate about the optimal pore size. Different cell types may have varied requirements for morphology [77][78][90,91]. Additionally, due to cracks and interconnected pores, their durability and wear resistance require attention [79][20].