Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Kaitano Dube.

Oceans play a vital role in socioeconomic and environmental development by supporting activities such as tourism, recreation, and food provision while providing important ecosystem services. However, concerns have been raised about the threat that climate change poses to the functions of oceans.

- marine biodiversity

- climate change adaptation

- marine protected areas (MPAs)

- habitat restoration

1. Introduction

Oceans play a central role in the socioeconomic development of many countries worldwide [1,2,3][1][2][3]. They provide numerous ecosystem services [4]. As a result, a significant portion of the population (about 40%) resides near the coastline [5]. Oceans also serve as recreational and tourist destinations [6]. Many coastal areas have multiple beaches, attracting millions of people who come to enjoy these tourism offerings [7,8,9][7][8][9]. In addition to beaches, oceans are utilised by tourists and recreation enthusiasts for activities such as snorkelling, water sports, and other recreational pursuits that are crucial for human well-being and development in the context of marine tourism [10]. These tourism activities support millions of jobs, livelihoods, and communities [11].

Oceans are home to numerous species of plants and animals [12,13][12][13]. These marine animals and plant species are crucial for maintaining a vibrant marine ecosystem and biodiversity. Some of these animals and plants are harvested and utilised by humans daily. Marine fish, for example, are consumed by people from all social classes and are an important source of nutrition [14]. In many impoverished communities, fish species effectively address issues of malnutrition and food insecurity [15]. Ocean fish also play a central role in poverty alleviation efforts in fish-dependent communities [16,17][16][17].

Oceans are central in weather and climate, as they determine weather systems [18,19][18][19]. They also act as carbon sinks, making them crucial in the fight against climate change [20]. Additionally, oceans trap a significant amount of heat [21,22][21][22], helping to regulate global temperatures, which are increasing because of global warming. Because of these factors, oceans are considered essential in driving several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [23]. Through various mechanisms, oceans can contribute to addressing the global challenges society faces today.

Oceans have faced multiple challenges and threats from anthropogenic activities despite their importance. The current challenges of climate change have not spared them [24,25,26][24][25][26]. The growth in the global human population has burdened the oceans [27[27][28],28], leading to immense pollution. Plastic from various human activities is an ocean eyesore and a threat to marine life [29]. Additionally, the oceans have suffered greatly from devastating oil spills that have harmed marine life [30], threatening their sustainability. From a climate perspective, the oceans have borne the brunt of rising sea levels [31[31][32],32], ocean acidification [33], and global warming, resulting in ocean warming [34].

In recognition of the threats faced by the oceans, the United Nations has declared the period from 2021 to 2030 as the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. This initiative aims to celebrate the role of oceans while also addressing and tackling the various threats they face. The Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development calls for increased ocean research to better understand these threats and find solutions, including climate change [35].

2. Publication Trends in Climate Change and Marine Biodiversity

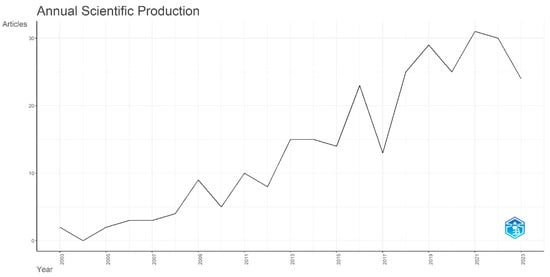

This examined materials published in Scopus Index journal outlets from 2003 to 2023 (Figure 21). It found that the number of articles studying climate change, marine biodiversity, and adaptation increased from about 2 publications to over 25 publications by the end of 2023. Overall, there has been a consistent rise in the number of publications addressing these topics. This increase can be attributed to the growing challenges faced by marine biodiversity due to the escalating impact of climate change.

Figure 21.

Trend in the number of publications on climate change and marine biodiversity adaptation.

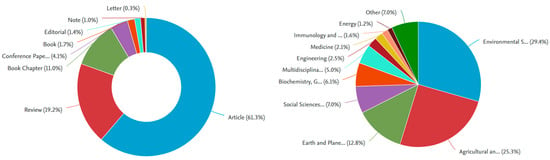

Figure 32.

Marine biodiversity adaptation and climate change publication outlets and research areas.

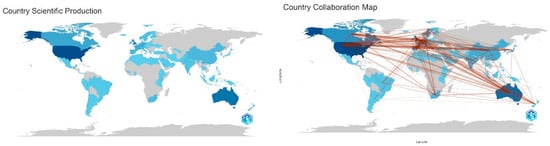

Figure 43.

Publishing countries and collaborations between countries.

3. Research Focus Area in Climate Change and Marine Biodiversity

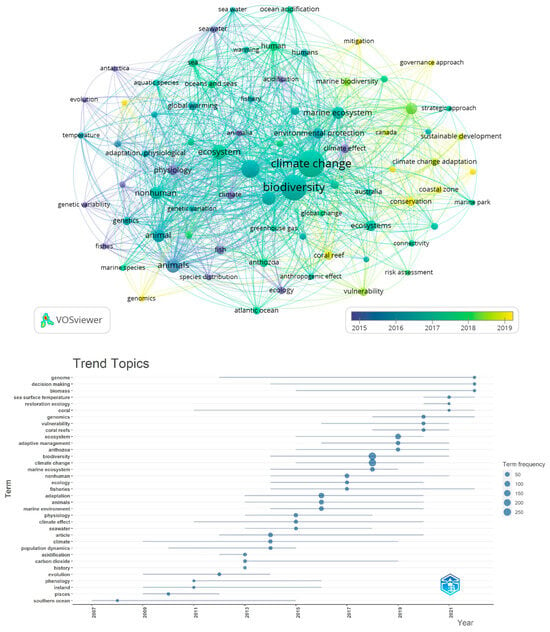

Over time, there has been an evolution in the discussions about climate change, marine biodiversity, and climate change, as shown in Figure 54. Climate change has been a central issue. There has been an acknowledgement that anthropogenic climate change has been responsible for multiple challenges affecting marine biodiversity. The work conducted thus far covers a range of issues that have transformed over time, given the evolving development within the climate change space.

Figure 54.

Trend in marine biodiversity and climate change, 2003–2023.

4. Impact of Climate Change on Marine Biodiversity

Chaudhary et al. [37][36], one of the most cited scholars in the field of climate change and marine biodiversity, cite global warming as a key driver of climate change, which poses a challenge to marine biodiversity. The increase in sea surface temperatures, a topic that has been extensively researched in the field of climate change and marine biodiversity (Figure 54), is believed to be responsible for latitudinal shifts in marine species. as temperatures rise, there has been a decline in species and species richness along the equator, with species moving towards the poles in search of more suitable habitats. These findings are supported by other scholars, such as Lin et al. [38][37], who studied marine fish at various taxonomic levels and observed decreased species diversity at the equator, with the Northern Hemisphere having greater species diversity. In another study, Lin et al. [39][38] found that the number of fish species with higher taxon and phylogenetic similarity decreases with latitude and ocean depth because of climate change. Lin and Costello [40][39] also found that fish body size and trophic level increase with latitude because of climate change, likely because of changes in temperature and oxygen levels. On the other hand, Manes et al. [41][40] noted that the projected increase in temperature could lead to the extinction of endemic marine and island species. These changes concern ecologists and the general population that relies on fish species, as they can limit access to critical protein sources, particularly in developing countries. The increase in water temperature is blamed for altering water’s physical and chemical quality by causing changes in its oxygen levels. An increase in water temperature reduces the solubility of oxygen in ocean water. This has resulted in declining oxygen levels in ocean water and coastal waters, with serious adverse effects on biogeochemical cycles and global food security [42][41]. According to Santos [43][42], the decline in oxygen in sandy beaches has resulted in changes in pH, which have been linked to declines in species richness and the extinction of certain species. Kim et al. [44][43] conducted a comprehensive study of 741 scleractinian coral species from various parts of the world. They found that coral reefs are under immense pressure and vulnerability worldwide. The highest vulnerabilities were noted in the tropics, specifically in areas close to the equator in America; the Southwest African tropics; and areas around Australasia’s tropics, particularly in areas surrounding Australia. Coral in high latitudes was found to be less vulnerable than in the tropics. The extreme weather events unleashed by climate change and anthropogenic activities have contributed to this vulnerability. The tropics have witnessed several extreme weather events that threaten coral reefs, such as increased heatwaves. Holbrook et al. [45][44] found that the occurrence of marine heatwaves is a challenge, causing the destruction of marine life and biodiversity and requiring adaptive measures to be put in place. This notion was supported by Welch et al. [46][45], who argued that observed marine heatwave episodes have resulted in shifts in various marine species, including marine predators. The Southern Hemisphere and coastal species have been particularly affected, and the highest impact has been felt in areas that have experienced the highest intensity of marine heatwaves. The fisheries were equally affected by marine heatwaves between 2015 and 2018, raising societal concerns. Marine heatwaves resulted in a drastic decline in fish stocks at a rapid rate and a decrease in other biodiversity [47][46]. Consequently, it is easy to see that climate change has implications for the physiology of flora and fauna, ultimately affecting species richness and diversity. Apart from suffering the harsh realities of global warming caused by anthropogenic-driven climate change, tropical species must also battle other extreme weather events that adversely impact coral reefs. Extreme weather events, such as tropical cyclones in some coral-reef-rich regions, like the Southwest Indian Ocean [48][47], have faced tremendous tropical cyclones in the recent past, which could have damaged mangroves and coral reefs. High tides and high winds that often characterise tropical cyclones can physically damage coral reefs. Cheal et al. [49][48] found that tropical cyclones of higher intensity have severely damaged large swaths of coral reefs in the Great Barrier Reef, with the worst expected as tropical cyclones are expected to increase their intensity with increased global warming [50][49]. While Dixon et al. [51][50] acknowledged the risk to coral reefs from tropical cyclones, they also noted the complexity of this risk as some downscaled data point to mixed results depending on the characteristics of cyclones in Western Australia. In Madagascar, a study of the relationship between tropical cyclones and coral reefs found that tropical cyclones have decreased coral cover by 1.4% to 45.8% because of the damaging effect of wind and sea surges. Nevertheless, evidence shows that these corals have recovered and exceeded pre-cyclone periods after these tropical cyclones. Of concern are the adverse changes in the taxonomic structure of corals that emerge after a tropical cyclone, which could alter the aquatic ecosystem of coral reefs. In Taiwan, Lin et al. [52][51] found the impact of tropical cyclones to be damaging in marine protected areas. This pattern is more or less the same in other areas with coral reefs, such as the Philippines [53][52] and other areas in the Americas that are prone to tropical cyclones. Changes in rainfall patterns also have an effect on ocean biodiversity. Changes in precipitation patterns can increase freshwater runoff and sediments in coastal waters. This can smother corals and disrupt their delicate balance with surrounding marine life. This is supported by Adam et al. [54][53], who argued that rainfall patterns on land impact coral communities and their biodiversity. Haapkylä et al. [55][54] argued that increased rainfall results in diseases for corals near the shore, which leads to biodiversity loss. Undoubtedly, the increased incidence of drought would affect biodiversity in coastal communities, as it will alter sea–land water interactions, resulting in changes in the chemical composition of the water. This could be compounded by the rise in sea levels, resulting in changes to the ocean ecosystem [56][55]. Other land activities, such as global warming, can affect the productivity of sea turtles and their food chain in the ocean [57][56]. Sea level rise, one of the global community’s challenges, is also challenging for marine biodiversity in many respects [58][57]. Rising sea levels can significantly impact coastal ecosystems, including algal rims and plant communities in salt marshes. Part of the observed evidence of the destructive effects of rising sea levels is the destruction of mangroves, critical habitats for marine species [59][58]. Mangroves have suffered the worst of various aspects of climate change, including rising sea levels, destruction from coastal erosion due to rising sea levels, and coastal flooding [60,61,62][59][60][61].References

- Nash, K.L.; van Putten, I.; Alexander, K.A.; Bettiol, S.; Cvitanovic, C.; Farmery, A.K.; Flies, E.J.; Ison, S.; Kelly, R.; Mackay, M.; et al. Oceans and society: Feedbacks between ocean and human health. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 161–187.

- Fleming, L.E.; Rabbottini, L.; Depledge, M.H.; Alcantara-Creencia, L.; Gerwick, W.H.; Goh, H.C.; Bennett, B. Overview of Oceans and Human Health. In Oceans and Human Health; Lora, L.B.-G., Fleming, E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–20.

- Baker, S.; Constant, N.; Nicol, P. Oceans justice: Trade-offs between Sustainable Development Goals in the Seychelles. Mar. Policy 2023, 147, 105357.

- Cordero-Penín, V.; Abramic, A.; García-Mendoza, A.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Haroun, R. Mapping marine ecosystem services potential across an oceanic archipelago: Applicability and limitations for decision-making. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 60, 101517.

- Barros-Platiau, A.F.; Câmara, P.E.; de Oliveira, C.C.; Granja e Barros, F.H. Ocean Governance in the Anthropocene: A New Approach in the Era of Climate Emergency. In Eco-Politics and Global Climate Change; Tripathi, S.B., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 59–72.

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G.; Mearns, K. Beyond’s response to the twin challenges of pollution and climate change in the context of SDGs. In Scaling up SDGs Implementation: Emerging Cases from State, Development and Private Sectors; Nhamo, G.O., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 87–98.

- Papageorgiou, M. Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 129, 44–48.

- Yustika, B.P.; Goni, J.I.C. Network Structure in Coastal and Marine Tourism: Diving into the Three Clusters. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 515–536.

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Townsel, A.; Gonzales, C.M.; Haas, A.R.; Navarro-Holm, E.E.; Salorio-Zuñiga, T.; Johnson, A.F. Nature-based marine tourism in the Gulf of California and Baja California Peninsula: Economic benefits and key species. Nat. Resour. Forum 2020, 44, 111–128.

- Morse, M.; McCauley, D.; Orofino, S.; Stears, K.; Mladjov, S.; Caselle, J.; Clavelle, T.; Freedman, R. Preferential selection of marine protected areas by the recreational scuba diving industry. Mar. Policy 2024, 159, 105908.

- Farjami, H.; Azizpour, J.; Andi, S. Manifestation of internal waves in the Southern Caspian Sea using satellite imagery. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 69, 103294.

- Christensen, V.; Coll, M.; Buszowski, J.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Frölicher, T.; Steenbeek, J.; Stock, C.A.; Watson, R.A.; Walters, C.J. The global ocean is an ecosystem: Simulating marine life and fisheries. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015, 24, 507–517.

- Davenport, T. Singapore and the Protection of the Marine Environment. In Peace with Nature: 50 Inspiring Essays on Nature and the Environment; Koh, T., Lye, H., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2024; pp. 63–68.

- Pradhan, S.K.; Nayak, P.K.; Haque, C.E. Mapping Social-Ecological-Oriented Dried Fish Value Chain: Evidence from Coastal Communities of Odisha and West Bengal in India. Coasts 2023, 3, 45–73.

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Ferrari, M.; Gonzalez, A.; Yusubova, L. Could Deep-Sea Fisheries Contribute to the Food Security of Our Planet? Pros and Cons. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14778.

- Robles-Zavala, E. Coastal livelihoods, poverty and well-being in Mexico. A case study of institutional and social constraints. J. Coast. Conserv. 2014, 18, 431–448.

- Damasio, L.M.A.; Pennino, M.G.; Villasante, S.; Carvalho, A.R.; Lopes, P.F.M. Adaptive factors and strategies in small-scale fisheries economies. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 739–750.

- Zhang, D.; Chiodi, A.; Zhang, C.; Foltz, G.; Cronin, M.; Mordy, C.; Cross, J.; Cokelet, E.; Zhang, J.; Meinig, C.; et al. Observing Extreme Ocean and Weather Events Using Innovative Saildrone Uncrewed Surface Vehicles. Oceanography 2023, 36, 70–77.

- Alsayed, A.Y.; Alsaafani, M.A.; Al-Subhi, A.M.; Alraddadi, T.M.; Taqi, A.M. Seasonal Variability in Ocean Heat Content and Heat Flux in the Arabian Gulf. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 532.

- Gruber, N.; Bakker, D.C.; DeVries, T.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Müller, J.D. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 119–134.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M. Interannual variations of heat budget in the lower layer of the eastern Ross Sea shelf and the forcing mechanisms in the Southern Ocean State Estimate. Int. J. Clim. 2023, 43, 5055–5076.

- SO-CHIC Consortium; Sallée, J.B.; Abrahamsen, E.P.; Allaigre, C.; Auger, M.; Ayres, H.; Zhou, S. Southern ocean carbon and heat impact on climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2023, 381, 20220056.

- Pandey, U.C.; Nayak, S.R.; Roka, K.; Jain, T.K. Oceans and Sustainable Development. In SDG14–Life Below Water: Towards Sustainable Management of Our Oceans; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 17–42.

- Laubenstein, T.; Smith, T.F.; Hobday, A.J.; Pecl, G.T.; Evans, K.; Fulton, E.A.; O’Donnell, T. Threats to Australia’s oceans and coasts: A systematic review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 231, 106331.

- Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Smith, T.F.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. Analyzing the impact and evolution of ocean & coastal management: 30 years in retrospect. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 242, 106697.

- Armoudian, M.; Stevens, G.; Stephenson, F.; Ellis, J. New Zealand’s media and the crisis in the ocean: News norms and scientific urgency. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2023, 33, 606–619.

- Halpern, B.S.; Walbridge, S.; Selkoe, K.A.; Kappel, C.V.; Micheli, F.; d’Agrosa, C.; Watson, R. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 2008, 319, 948–952.

- Mai, L.; He, H.; Sun, X.F.; Zeng, E.Y. Riverine inputs of land-based microplastics and affiliated hydrophobic organic contaminants to the global oceans. In Microplastic Contamination in Aquatic Environments; Zeng, E.Y., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 311–329.

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Ben-Haddad, M.; Nicoll, K.; Galgani, F.; Neal, W.J. Marine plastic pollution in the Anthropocene: A linguistic toolkit for holistic understanding and action. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 248, 106967.

- Samra, R.M.A.; Ali, R. Tracking the behavior of an accidental oil spill and its impacts on the marine environment in the Eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115887.

- Dube, K.; Chapungu, L.; Fitchett, J. Meteorological and Climatic Aspects of Cyclone Idai and Kenneth. In Cyclones in Southern Africa; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Nhamo, G., Dube, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–36.

- Mgadle, A.; Dube, K.; Lekaota, L. Conservation and Sustainability of Coastal City Tourism in the Advent of Seal Level Rise in Durban, South Africa. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2022, 17, 179–196.

- Figuerola, B.; Hancock, A.M.; Bax, N.; Cummings, V.J.; Downey, R.; Griffiths, H.J.; Stark, J.S. A review and meta-analysis of potential impacts of ocean acidification on marine calcifiers from the Southern Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 584445.

- Baag, S.; Mandal, S. Combined effects of ocean warming and acidification on marine fish and shellfish: A molecule to ecosystem perspective. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 802, 149807.

- Pearlman, J.; Buttigieg, P.L.; Bushnell, M.; Delgado, C.; Hermes, J.; Heslop, E.; Hörstmann, C.; Isensee, K.; Karstensen, J.; Lambert, A.; et al. Evolving and Sustaining Ocean Best Practices to Enable Interoperability in the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 619685.

- Chaudhary, C.; Richardson, A.J.; Schoeman, D.S.; Costello, M.J. Global warming is causing a more pronounced dip in marine species richness around the equator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2015094118.

- Lin, H.; Corkrey, R.; Kaschner, K.; Garilao, C.; Costello, M.J. Latitudinal diversity gradients for five taxonomic levels of marine fish in depth zones. Ecol. Res. 2021, 36, 266–280.

- Lin, H.-Y.; Wright, S.; Costello, M.J. Numbers of fish species, higher taxa, and phylogenetic similarity decrease with latitude and depth, and deep-sea assemblages are unique. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16116.

- Lin, H.-Y.; Costello, M.J. Body size and trophic level increase with latitude, and decrease in the deep-sea and Antarctica, for marine fish species. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15880.

- Manes, S.; Costello, M.J.; Beckett, H.; Debnath, A.; Devenish-Nelson, E.; Grey, K.-A.; Jenkins, R.; Khan, T.M.; Kiessling, W.; Krause, C.; et al. Endemism increases species’ climate change risk in areas of global biodiversity importance. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 257, 109070.

- Breitburg, D.; Levin, L.A.; Oschlies, A.; Grégoire, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Conley, D.J.; Garçon, V.; Gilbert, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Isensee, K.; et al. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 2018, 359, eaam7240.

- Santos, D. Offshore extinctions: Ocean acidification impacting interstitial fauna. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 6859–6864.

- Kim, S.W.; Sommer, B.; Beger, M.; Pandolfi, J.M. Regional and global climate risks for reef corals: Incorporating species-specific vulnerability and exposure to climate hazards. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 4140–4151.

- Holbrook, N.J.; Gupta, A.S.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Hobday, A.J.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Scannell, H.A.; Smale, D.A.; Wernberg, T. Keeping pace with marine heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 482–493.

- Welch, H.; Savoca, M.S.; Brodie, S.; Jacox, M.G.; Muhling, B.A.; Clay, T.A.; Cimino, M.A.; Benson, S.R.; Block, B.A.; Conners, M.G.; et al. Impacts of marine heatwaves on top predator distributions are variable but predictable. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5188.

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Frölicher, T.L. Marine heatwaves exacerbate climate change impacts for fisheries in the northeast Pacific. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6678.

- Dube, K. Tourism and climate change vulnerabilities: A focus on African destinations. In Handbook on Tourism and Conservation; Mbaiwa, J.E., Kolawole, O.D., Hambira, W.L., Mogende, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 86–100.

- Cheal, A.J.; MacNeil, M.A.; Emslie, M.J.; Sweatman, H. The threat to coral reefs from more intense cyclones under climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 1511–1524.

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G.; Chikodzi, D. Rising sea level and its implications on coastal tourism development in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100346.

- Dixon, A.M.; Puotinen, M.; Ramsay, H.A.; Beger, M. Coral Reef Exposure to Damaging Tropical Cyclone Waves in a Warming Climate. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002600.

- Lin, Y.-C.; Feng, S.-N.; Lai, C.-Y.; Tseng, H.-T.; Huang, C.-W. Applying deep learning to predict SST variation and tropical cyclone patterns that influence coral bleaching. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102261.

- Price, B.A.; Harvey, E.S.; Mangubhai, S.; Saunders, B.J.; Puotinen, M.; Goetze, J.S. Responses of benthic habitat and fish to severe tropical cyclone Winston in Fiji. Coral Reefs 2021, 40, 807–819.

- Adam, T.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Holbrook, S.J.; Carpenter, R.C.; Claudet, J.; Loiseau, C.; Thiault, L.; Brooks, A.J.; Washburn, L.; Schmitt, R.J. Landscape-scale patterns of nutrient enrichment in a coral reef ecosystem: Implications for coral to algae phase shifts. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2227.

- Haapkylä, J.; Unsworth, R.K.; Flavell, M.; Bourne, D.G.; Schaffelke, B.; Willis, B.L. Seasonal rainfall and runoff promote coral disease on an inshore reef. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16893.

- Dube, K.; Chikodzi, D. Examining current and future challenges of sea level rise on coastal national parks. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 50, 1573–1580.

- Sibitane, Z.E.; Dube, K.; Lekaota, L. Global Warming and Its Implications on Nature Tourism at Phinda Private Game Reserve, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5487.

- Prakash, S. Impact of climate change on aquatic ecosystem and its biodiversity: An overview. Int. J. Biol. Innov. 2021, 3, 312–317.

- Befus, K.M.; Barnard, P.L.; Hoover, D.J.; Hart, J.A.F.; Voss, C.I. Increasing threat of coastal groundwater hazards from sea-level rise in California. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 946–952.

- Ellison, J.C. Vulnerability assessment of mangroves to climate change and sea-level rise impacts. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 23, 115–137.

- Cohen, M.C.; Figueiredo, B.L.; Oliveira, N.N.; Fontes, N.A.; França, M.C.; Pessenda, L.C.; de Souza, A.V.; Macario, K.; Giannini, P.C.; Bendassolli, J.A.; et al. Impacts of Holocene and modern sea-level changes on estuarine mangroves from northeastern Brazil. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2020, 45, 375–392.

- Xiao, H.; Su, F.; Fu, D.; Wang, Q.; Huang, C. Coastal Mangrove Response to Marine Erosion: Evaluating the Impacts of Spatial Distribution and Vegetation Growth in Bangkok Bay from 1987 to 2017. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 220.

More