You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Adam de Smith and Version 3 by Lindsay Dong.

Acute leukemias, mainly consisting of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), comprise a major diagnostic group among hematologic cancers. Due to the early age at onset of ALL, particularly, it has long been suspected that acute leukemias of childhood may have an in utero origin.

- leukemia

- prenatal risk factors

- newborn screening

- twins

1. Introduction

Circumstantial evidence for an in utero origin for childhood acute leukemias is threefold. In pediatric acute leukemias, the young age at onset alone, especially for ALL during the early-life peak, suggests prenatal leukemogenesis; since most cancers are thought to require the sequential acquisition of two or more somatic “hits” over time, in children with cancer diagnosed under five years of age, the process is thought to extend into the prenatal period of necessity. However, this presumption of in utero origins diminishes with older age at diagnosis. Acute leukemias occur in developing hematopoietic cells, which are present across the age span, but some populations of cells vulnerable to transformation are known to comprise a much larger proportion of total hematopoietic cells in fetal versus adult life [1][8]. Lastly, these patterns have focused the epidemiology of childhood on pregnancy as a critical window of risk. The fact that many pathologies of pregnancy, maternal exposures during gestation, and perinatal characteristics have been consistently associated with acute leukemias also circumstantially supports their in utero origin.

There are three lines of direct evidence for an in utero origin for acute leukemias. First, there are a small number (<20) of case reports of prenatal diagnosis of leukemia in the literature [2][9]. While these reports do not establish the frequency with which acute leukemia develops in utero, they provide definitive proof of the principle that it can happen. Twins, particularly the study of twins concordant for acute leukemia, provide a second line of evidence. Finally, there is a small but robust literature on “backtracking” acute leukemia patients’ somatic alterations to samples taken at birth (i.e., dried blood spots or umbilical cord blood).

2. Twin Studies

The occurrence of concordant childhood leukemia arising in twins was first recorded in the medical literature in 1882 in Germany [3][10]. By the middle of the 20th century, several case reports of concordant leukemia in twins had been noted, and based on these findings, review papers published in the 1960s and 1970s proposed the prenatal origins of childhood leukemia [3][4][5][10,11,12]. By the beginning of the 21st century, over 70 twin pairs with concordant childhood leukemia were reported in the literature, including at least 37 ALL and 17 AML twin diagnoses [3][10]. The majority of the reported concordant leukemias in twins were diagnosed in children younger than 5 years of age, with approximately half of the concordant pairs being diagnosed with infant leukemia (i.e., <1 year of age), a proportion of total childhood leukemias much higher than that found in singleton cases. The concordance rate for acute leukemia in monozygotic (MZ) twins, reported to be between 5% and 25%, is vastly higher than the concordance rate of leukemia in dizygotic, or fraternal, twins, in whom concordant leukemias are exceedingly rare. Such a large difference was unlikely to be due to a shared genetic predisposition in MZ twins, and instead, a proposed mechanism that could plausibly explain the high concordance rate of leukemia in MZ twins was their shared placental vasculature [3][5][6][10,12,13]. Approximately 60% of MZ twins develop in a single monochorionic placenta, which leads to vascular anastomoses that facilitate the passage of blood cells between the circulation of each twin [7][14]. Thus, it was proposed that an initiating leukemogenic lesion could develop in one twin and then be transferred to the other through the shared placental vasculature [5][12]. This hypothesized mechanism of twin-to-twin transfusion of preleukemic clones was subsequently confirmed by molecular genetic analyses of acute leukemias in concordant twin pairs. In particular, the detection of identical fusion events in MZ twins concordant for leukemia supports a common clonal origin, given that the independent generation of leukemia-forming translocations with identical breakpoints in both twins is highly unlikely. Ford and colleagues first demonstrated this in three pairs of MZ twins concordant for KMT2A-rearranged infant ALL, whereby each twin pair shared the same-sized restriction fragments of KMT2A [8][15]. Studies of leukemia in twins have also been informative regarding the timing of mutational events that initiate or drive the progression to overt leukemia in children. In twins concordant for infant leukemia, the latency period between the diagnosis of leukemia in both twins is relatively short. However, a wide variation in age of leukemia diagnosis has been observed in twins concordant for childhood ALL, with latency periods of up to 14 years reported in one twin pair [3][9][10,17]. This supports a two-hit mechanism of leukemogenesis, whereby the initiating lesion develops prenatally, and then secondary somatic mutations arise in the postnatal period, resulting in progression to acute leukemia. Genetic studies in twins concordant for ALL have provided strong evidence for this two-hit model, with several reported instances of distinct secondary somatic mutations and copy-number alterations in twins that share the same gene fusion or other initiating events [10][11][12][22,24,25]. Further support is provided by twins discordant for childhood ALL, in which preleukemic clones harboring the initiating lesion, such as ETV6-RUNX1 fusion, have been found to persist for several years in the healthy co-twin without leading to the development of leukemia, supporting the supposition that additional mutations are required for overt leukemia development [11][13][14][15][19,24,26,27]. The timing of mutational events that drive the development of childhood AML is less clear, as fewer twin pairs with AML have been investigated, although a protracted latency period between the onset of AML in at least one concordant twin pair has been reported [16][28].3. Prenatal Risk Factors for Acute Leukemia in Childhood

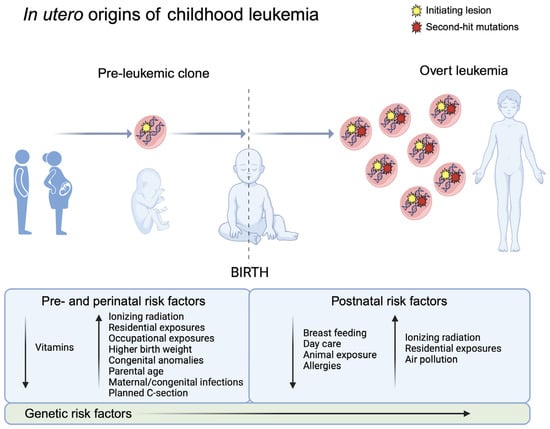

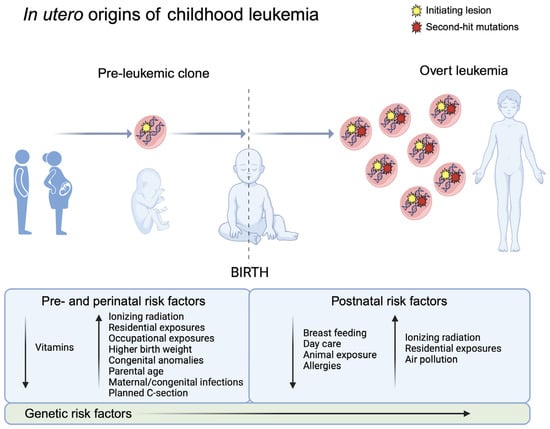

Twin and backtracking studies have clearly focused epidemiologic investigations of childhood acute leukemia on pregnancy (Figure 14). The prenatal period appears to be susceptible to translocations as well as chromosomal aneuploidies that can lead to childhood leukemia—whether this is because of the vulnerabilities of specific cell types in early hematopoiesis or due to particular exposures during pregnancy that may drive the formation of these genetic lesions remains to be determined.

Figure 14. Natural history of childhood leukemia development supports in utero origins. Evidence from monozygotic twins concordant for childhood leukemia and the backtracking of somatic alterations to newborn blood samples support the prenatal development of initiating lesions in childhood leukemia (left), e.g., ETV6-RUNX1 fusions in childhood ALL. In the two-hit model of childhood leukemia development, the postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations is followed by clonal expansion, leading to the development of overt acute leukemia (right). Created with Biorender.com.

3.1. Pathologies of Pregnancy

The association of childhood leukemia with maternal diabetes, both pre-existing and gestational, as well as with the correlated trait of body mass index, was the subject of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Marley et al. [17][61]. Through the aggregation of the results of 34 studies, the authors found that any maternal diabetes during pregnancy raised the risk of ALL (odds ratio (OR) = 1.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.28 to 1.67), even after including only analyses adjusted for birth weight (OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.29 to 2.34). Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index was positively associated with any leukemia in childhood (OR per five-unit increase in body max index = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.11). There were no associations of maternal diabetes or body mass index with AML, specifically.

3.2. Maternal Exposures

Diagnostic irradiation in pregnant women has long been suspected of contributing to leukemia risk in their offspring. Wakeford and Bithell reviewed studies conducted over 65 years [18][64]. A meta-analysis of case–control and case–cohort studies found a significantly higher risk of any childhood leukemia among the offspring of mothers who were exposed to diagnostic irradiation during pregnancy (relative risk (RR) = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.16 to 1.41) and in particular those who were exposed to diagnostic irradiation to the abdomen (RR = 1.82, 95% CI = 0.90 to 3.66). These associations are generally taken to be causal, resulting in successful efforts to reduce the use of diagnostic irradiation with pregnant women [19][65]. The Childhood Cancer and Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC) has conducted several large, pooled analyses of maternal occupational and residential exposures during pregnancy. Maternal occupational exposure to pesticides was not associated with ALL (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.78 to 1.30) but was strongly and significantly associated with AML (OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.19 to 3.18) [20][66]. Neither ALL nor AML was significantly associated with maternal occupational paint exposure during pregnancy [21][67]. Home pesticide exposure during pregnancy was significantly associated with both childhood ALL (OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.32 to 1.54) and AML (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.21 to 1.99) [22][68]. Home paint exposure during pregnancy was significantly associated with ALL, albeit to a lesser degree than pesticides (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.25).3.3. Perinatal Characteristics

The association of birth weight with childhood acute leukemia has been apparent for decades [23][75]. The latest meta-analysis of the topic included 28 studies published through 2021 [24][76]. As has long been known, high birth weight (>4000 g) was associated with a higher risk of ALL (OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.20 to 1.35) compared to normal birth weight (2500–4000 g), while low birth weight (<2500 g) was associated with lower risk (OR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.92). There was a null association of high and low birth weight with AML, although the association with high birth weight was suggestive (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.97–1.56). Others have refined this analysis to examine size for gestational age [25][77] or percent of optimal birth weight [26][78], but the overall findings that larger babies have a somewhat higher risk of ALL remains the case. Interestingly, the degree of association between birth weight and ALL seems to differ by molecularly defined subtype [27][79]. Higher parental age at birth of offspring is consistently associated with both ALL and AML. CLIC has produced the most comprehensive analyses of parental age and ALL [28][80] and AML [29][81] to date. Focusing on the population-based studies created by record linkage, which would not suffer from selection bias, there was a significant association of maternal age with ALL (OR per 5-year increase = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.08). Similarly, there was an increased risk of AML among children of mothers > 40 years of age at delivery (OR = 6.87, 95% CI: 2.12–22.25). Neither study identified associations with paternal age, although since maternal and paternal age are highly correlated, it is difficult to disentangle them. Paternal age and, to a lesser extent, maternal age are both associated with a higher burden of de novo mutations in offspring [30][82], which is a plausible but as-yet unexamined [31][83] explanation for the epidemiologic association of childhood acute leukemia with parental age. There are, however, many demographic, obstetric, and behavioral correlates of maternal age [32][84] which raise the question of the extent to which confounding affects maternal age associations with childhood acute leukemias.4. Opportunities for Prevention

Natural history studies of childhood acute leukemias in twins and backtracking studies have clearly revealed that most disease has an initiating somatic event in utero and a secondary event postnatally. Consequently, a fair number of maternal exposures during gestation and pregnancy characteristics appear to modify the risk of acute leukemia in offspring. The aggregate data are sufficient to suggest several potential routes for screening and prevention of childhood acute leukemia. Promoting behaviors or exposures that confer lower risk would thus be a form of primary prevention. There also could be efforts to create prenatal risk indices based on the known risk factors for offspring leukemia, modifiable or not. These could be enhanced with the addition of maternal genetics that influence offspring risk of leukemia, an almost entirely unexamined area of research. To date, there has been very little epidemiology of pre-leukemia, owing in large part to the cumbersome assays for detecting it. The development of more robust, scalable assays for pre-leukemia at birth—in DBSs since they are the most abundant newborn sample—would enable widespread studies evaluating the association of prenatal risk indices with the detection of pre-leukemia. Screening for pre-leukemia at birth seems potentially feasible from a technical standpoint but will face ethical and practical challenges. Most notably, any test is likely to be probabilistic rather than deterministic, and many leukemias occur past infancy; both these facts would seem to disqualify acute leukemia from inclusion in newborn screening programs, although norms are changing. If newborn screening for childhood acute leukemia were enabled, the end goal would be prevention. One could envision attempting early detection by periodic sampling of blood to detect any change in translocation prevalence. However, this faces hurdles with compliance since sampling blood from babies and small children is generally avoided. More importantly, it may not be possible to sample often enough to capture the clonal expansion of fully transformed acute leukemia cells, which is generally thought to occur in a matter of days to a few weeks. Consequently, it is considerably more feasible to target children at higher risk of acute leukemias with efforts to either reduce their prevalence of pre-leukemia or reduce their likelihood of acquiring a secondary mutation that would tip them into progression to overt leukemia. Postnatal risk factors are coming into focus [33][60], many of which are modifiable and may suggest interventions.The identification of potentially modifiable risk factors in the prenatal period presents a window of opportunity for the primary prevention of childhood acute leukemia. Additional work is needed to determine the timing of the development of childhood leukemia subtypes that have not yet been examined, which will inform the extent to which we may be able to screen for and potentially prevent all childhood leukemias.