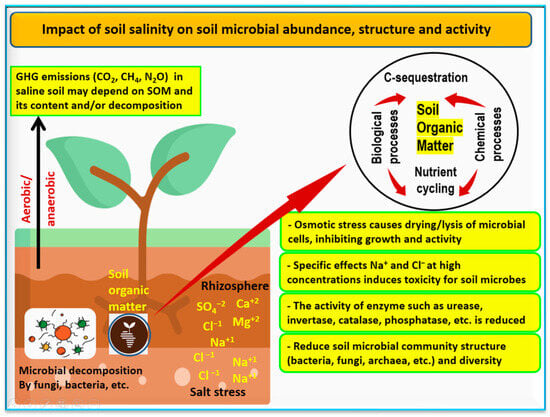

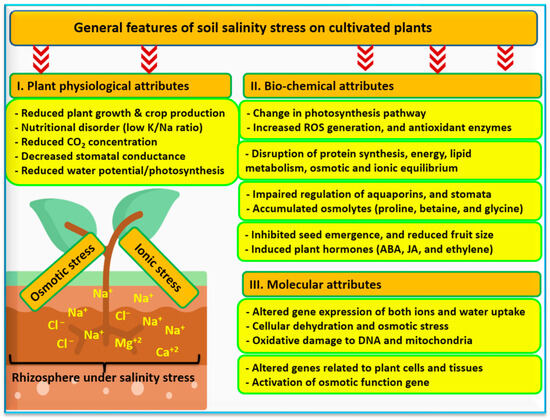

Soil salinity is a serious problem facing many countries globally, especially those with semi-arid and arid climates. Soil salinity can have negative influences on soil microbial activity as well as many chemical and physical soil processes, all of which are crucial for soil health, fertility, and productivity. Soil salinity can negatively affect physiological, biochemical, and genetic attributes of cultivated plants as well. Plants have a wide variety of responses to salinity stress and are classified as sensitive (e.g., carrot and strawberry), moderately sensitive (grapevine), moderately tolerant (wheat) and tolerant (barley and date palm) to soil salinity depending on the salt content required to cause crop production problems.

- salt stress

- salt-affected soil

- gypsum

- biochar

- compost

- PGPR

- mycorrhizae

1. Soil Salinity and Global Issues

2. Salt-Affected Soil Classification

| Soil Salinity Class | Electrical Conductivity (dS m | −1 | ) | Crop Response | Example Crop Tolerance Level (dS m | −1 | ) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Saline | 0–2 | No yield loss | Maize (1.7) | ||||

| Slightly Saline | 2–4 | Yield is reduced in sensitive crops | Peanut (3.2) | ||||

| Moderately Saline | 4–8 | Most crops experience reduced yields | Sorghum (6.8) | ||||

| Strongly Saline | 8–16 | Only tolerant crops produce viable yields | Rye (11.4) | ||||

| Very Strongly Saline | >16 | Only halophytes perform well | Halophytes |

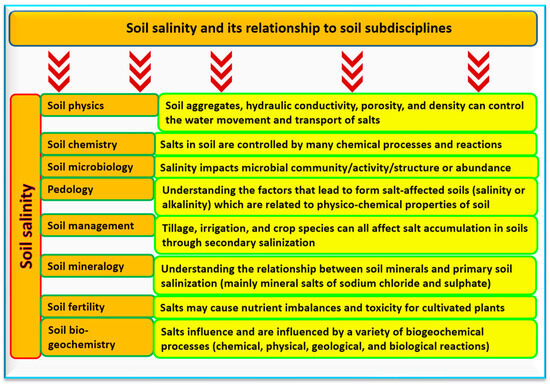

3. Soil Salinity from the Perspective of Different Soil Subdisciplines

3.1. Soil Biogeochemistry

3.2. Soil Microbiology

3.3. Soil Fertility and Plant Nutrition

4. Crop Response to Soil Salinity and Mechanisms

References

- Gupta, R.K.; Abrol, I.P.; Finkl, C.W.; Kirkham, M.B.; Arbestain, M.C. Soil salinity and salinization. In Encyclopedia of Soil Science; Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series; Chesworth, W., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008.

- Haj-Amor, Z.; Araya, T.; Kim, D.-G.; Bouri, S.; Lee, J.; Ghiloufi, W.; Yang, Y.; Kang, H.; Jhariya, M.K.; Banerjee, A.; et al. Soil salinity and its associated effects on soil microorganisms, greenhouse gas emissions, crop yield, biodiversity and desertification: A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 843, 156946.

- Talukder, B.; Salim, R.; Islam, S.T.; Mondal, K.P.; Hipel, K.W.; Vanloon, G.W.; Orbinski, J. Collective intelligence for addressing community planetary health resulting from salinity prompted by sea level rise. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2023, 10, 100203.

- Bannari, A.; Al-Ali, Z.A. Assessing climate change impact on soil salinity dynamics between 1987–2017 in arid landscape using Landsat TM, ETM+ and OLI data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2794.

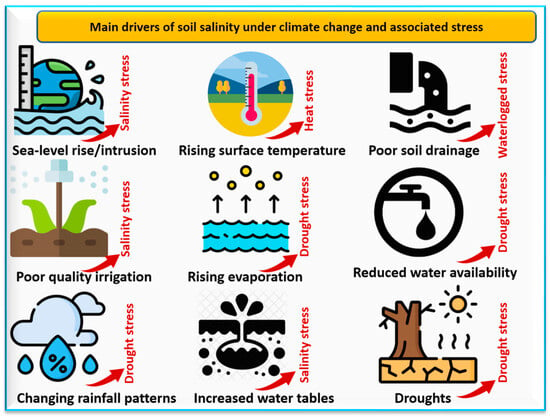

- Corwin, D.L. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 72, 842–862.

- Eswar, D.; Karuppusamy, R.; Chellamuthu, S. Drivers of soil salinity and their correlation with climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 310–318.

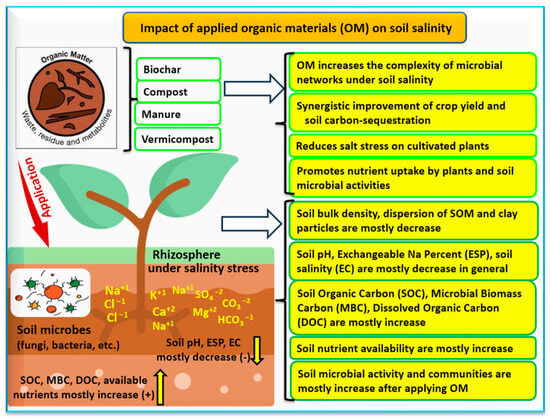

- Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, M. Synergistic improvement of carbon sequestration and crop yield by organic material addition in saline soil: A global meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 891, 164530.

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W. Drip irrigation in agricultural saline-alkali land controls soil salinity and improves crop yield: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 880, 163226.

- Navarro-Torre, S.; Garcia-Caparrós, P.; Nogales, A.; Abreu, M.M.; Santos, E.; Cortinhas, A.L.; Caperta, A.D. Sustainable agricultural management of saline soils in arid and semi-arid Mediterranean regions through halophytes, microbial and soil-based technologies. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 212, 105397.

- Khamidov, M.; Ishchanov, J.; Hamidov, A.; Donmez, C.; Djumaboev, K. Assessment of Soil Salinity Changes under the Climate Change in the Khorezm Region, Uzbekistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8794.

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712931.

- Liu, Y.; Xun, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R. Rhizosphere microbes enhance plant salt tolerance: Toward crop production in saline soil. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 6543–6551.

- Sundha, P.; Basak, N.; Rai, A.K.; Yadav, R.K.; Sharma, P.C. Irrigation water quality, gypsum, and city waste compost addition affect P dynamics in saline-sodic soils. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114559.

- Singh, A. Poor-drainage-induced salinization of agricultural lands: Management through structural measures. Land Use Policy 2018, 82, 457–463.

- Ullah, A.; Bano, A.; Khan, N. Climate Change and Salinity Effects on Crops and Chemical Communication Between Plants and Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms Under Stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 618092.

- Bhowmik, B.C.; Rima, N.N.; Gosh, K.; Hossain, A.; Murray, F.J.; Little, D.C.; Mamun, A.-A. Salinity extrusion and resilience of coastal aquaculture to the climatic changes in the southwest region of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13935.

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sarkar, B.; Jat, H.S.; Sharma, P.C.; Bolan, N.S. Soil salinity under climate change: Challenges for sustainable agriculture and food security. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111736.

- Schaetzl, R.; Thompson, M.L. Soils: Genesis and Geomorphology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Indorante, S.J.; Follmer, L.R.; Konen, M.E.; Bathgate, J.A.; D’Avello, T.P.; Rhanor, T.M. Sodium-Affected Soils in South-Central Illinois, USA: A Summary of Settings, Distribution, and Genesis Pathways. Soil Horiz. 2011, 52, 118–125.

- Richards, L. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; U.S. Department Agriculture Handbook 60; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954.

- Shahid, S.A.; Rahman, K. Soil salinity development, classification, assessment and management in irrigated agriculture. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 23–39.

- Soil Survey Staff. Soil Taxonomy: A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 436; Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- Soil Classification Working Group. The Canadian System of Soil Classification, 3rd ed.; Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Publication: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1998.

- Isbell, R.F. National Committee on Soil and Terrain. In The Australian Soil Classification., 3rd ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2021.

- Katerji, N.; van Hoorn, J.; Hamdy, A.; Mastrorilli, M. Salt tolerance classification of crops according to soil salinity and to water stress day index. Agric. Water Manag. 2000, 43, 99–109.

- FAO. Agricultural Drainage Water Management in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 61; Food and Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2002.

- Sahab, S.; Suhani, I.; Srivastava, V.; Chauhan, P.S.; Singh, R.P.; Prasad, V. Potential risk assessment of soil salinity to agroecosystem sustainability: Current status and management strategies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 764, 144164.

- Goswami, S.K.; Kashyap, A.S.; Kumar, R.; Gujjar, R.S.; Singh, A.; Manzar, N. Harnessing Rhizospheric Microbes for Eco-friendly and Sustainable Crop Production in Saline Environments. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 81, 14.

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.N.; Tiwari, R.K.; Sahu, P.K.; Yadav, J.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kumar, S. Salinity Alleviation and Reduction in Oxidative Stress by Endophytic and Rhizospheric Microbes in Two Rice Cultivars. Plants 2023, 12, 976.

- Ricks, K.D.; Ricks, N.J.; Yannarell, A.C. Patterns of Plant Salinity Adaptation Depend on Interactions with Soil Microbes. Am. Nat. 2023, 202, 276–287.

- Bouras, H.; Mamassi, A.; Devkota, K.P.; Choukr-Allah, R.; Bouazzama, B. Integrated effect of saline water irrigation and phosphorus fertilization practices on wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth, productivity, nutrient content and soil proprieties under dryland farming. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100295.

- Huang, K.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Rasul, F.; Shahzad, S.; Wu, C.; Shao, J.; Huang, G.; Li, R.; Almari, S.; et al. Soil acidification and salinity: The importance of biochar application to agricultural soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1206820.

- Islam, S.M.; Gaihre, Y.K.; Islam, M.N.; Jahan, A.; Sarkar, A.R.; Singh, U.; Islam, A.; Al Mahmud, A.; Akter, M.; Islam, R. Effects of integrated nutrient management and urea deep placement on rice yield, nitrogen use efficiency, farm profits and greenhouse gas emissions in saline soils of Bangladesh. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 909, 168660.

- Zhang, G.; Bai, J.; Zhai, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Hu, X. Microbial diversity and functions in saline soils: A review from a biogeochemical perspective. J. Adv. Res. 2023.

- Zheng, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.-S. Effect of planting salt-tolerant legumes on coastal saline soil nutrient availability and microbial communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118574.

- Sihi, D.; Dari, B. Soil Biogeochemistry. In The Soils of India; Mishra, B., Ed.; World Soils Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020.

- Zhen, Z.; Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Wei, T.; Li, H.; Huang, F.; Huang, Y.; Ren, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Accelerated nitrification and altered community structure of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in the saline-alkali tolerant rice rhizosphere of coastal solonchaks. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104978.

- Song, M.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Tian, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of effects of various carbon-rich amendments on overall soil quality and crop productivity in degraded soils. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116529.

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Fagodiya, R.K.; Narjary, B.; Barman, A.; Prajapat, K.; Kumar, S.; Bundela, D.S.; Sharma, P.C. Restoring soil quality and carbon sequestration potential of waterlogged saline land using subsurface drainage technology to achieve land degradation neutrality in India. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 885, 163959.

- Mao, X.; Yang, Y.; Guan, P.; Geng, L.; Ma, L.; Di, H.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Remediation of organic amendments on soil salinization: Focusing on the relationship between soil salts and microbial communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113616.

- Shaaban, M.; Wu, Y.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Peng, Q.A.; Lin, S.; Hu, R. Enzyme activities and organic matter mineralization in response to application of gypsum, manure and rice straw in saline and sodic soils. Environ. Res. 2023, 224, 115393.

- Cui, C.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Bioremediation of phenanthrene in saline-alkali soil by biochar- immobilized moderately halophilic bacteria combined with Suaeda salsa L. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 880, 163279.

- Alharbi, K.; Hafez, E.M.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Osman, H.S. Mitigating Osmotic Stress and Enhancing Developmental Productivity Processes in Cotton through Integrative Use of Vermicompost and Cyanobacteria. Plants 2023, 12, 1872.

- Song, X.; Li, H.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Shi, L. Biochar/vermicompost promotes Hybrid Pennisetum plant growth and soil enzyme activity in saline soils. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 183, 96–110.

- Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Cui, X.; Hou, D.; Jia, H.; Wang, S.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, A. Mitigating soil salinity stress with titanium gypsum and biochar composite materials: Improvement effects and mechanism. Chemosphere 2023, 321, 138127.

- Ran, C.; Gao, D.; Bai, T.; Geng, Y.; Shao, X.; Guo, L. Straw return alleviates the negative effects of saline sodic stress on rice by improving soil chemistry and reducing the accumulation of sodium ions in rice leaves. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108253.

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, F.; Chen, S.; Zhou, W. Integrated application of phosphorus-accumulating bacteria and phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria to achieve sustainable phosphorus management in saline soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163971.

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ryder, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Toh, R.; Yang, P.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Denton, M.D. Soil salinity determines the assembly of endophytic bacterial communities in the roots but not leaves of halophytes in a river delta ecosystem. Geoderma 2023, 433, 116447.

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, M.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Q.; Jin, S.; Huang, G. Lignite bioorganic fertilizer enhanced microbial co-occurrence network stability and plant–microbe interactions in saline-sodic soil. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 879, 163113.

- Somenahally, A.C.; McLawrence, J.; Chaganti, V.N.; Ganjegunte, G.K.; Obayomi, O.; Brady, J.A. Response of soil microbial Communities, inorganic and organic soil carbon pools in arid saline soils to alternative land use practices. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110227.

- Zhang, G.; Bai, J.; Jia, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C.; Chen, G. Soil microbial communities regulate the threshold effect of salinity stress on SOM decomposition in coastal salt marshes. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 868–879.

- Guangming, L.; Xuechen, Z.; Xiuping, W.; Hongbo, S.; Jingsong, Y.; Xiangping, W. Soil enzymes as indicators of saline soil fertility under various soil amendments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 237, 274–279.

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Miao, F.; Li, Z.; Tang, W.; Sun, J. Assessing the effect of soil salinization on soil microbial respiration and diversities under incubation conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 155, 103671.

- Heng, T.; Hermansen, C.; de Jonge, L.W.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Zhao, L.; He, X. Differential responses of soil nutrients to edaphic properties and microbial attributes following reclamation of abandoned salinized farmland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 347, 108373.

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, X.; Hao, B.; Guo, W. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi facilitate Astragalus adsurgens growth and stress tolerance in cadmium and lead contaminated saline soil by regulating rhizosphere bacterial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 187, 104842.

- Hu, M.; Sardans, J.; Le, Y.; Yan, R.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Tong, C. Biogeochemical behavior of P in the soil and porewater of a low-salinity estuarine wetland: Availability, diffusion kinetics, and mobilization mechanism. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118617.

- Wang, B.; Kuang, S.; Shao, H.; Cheng, F.; Wang, H. Improving soil fertility by driving microbial community changes in saline soils of Yellow River Delta under petroleum pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 304, 114265.

- Wu, L.; Yue, W.; Zheng, N.; Guo, M.; Teng, Y. Assessing the impact of different salinities on the desorption of Cd, Cu and Zn in soils with combined pollution. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 836, 155725.

- Atai, E.; Jumbo, R.B.; Cowley, T.; Azuazu, I.; Coulon, F.; Pawlett, M. Efficacy of bioadmendments in reducing the influence of salinity on the bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 892, 164720.

- Qian, S.; Zhou, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, B.; Yan, H.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Q.; Ye, H.; Qin, L.; Lai, C. Biochar-compost as a new option for soil improvement: Application in various problem soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 870, 162024.

- Bolan, N.; Sarmah, A.K.; Bordoloi, S.; Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Van Zwieten, L.; Sooriyakumar, P.; Khan, B.A.; Ahmad, M.; Solaiman, Z.M.; et al. Soil acidification and the liming potential of biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120632.

- Manzano, R.; Diquattro, S.; Roggero, P.P.; Pinna, M.V.; Garau, G.; Castaldi, P. Addition of softwood biochar to contaminated soils decreases the mobility, leachability and bioaccesibility of potentially toxic elements. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 739, 139946.

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar effects on soil biota—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836.

- Singh, B.P.; Cowie, A.L. Long-term influence of biochar on native organic carbon mineralisation in a low-carbon clayey soil. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3687.

- Mudare, S.; Li, M.; Kanomanyanga, J.; Lamichhane, J.R.; Lakshmanan, P.; Cong, W. Ecosystem services of organic versus inorganic ground cover in peach orchards: A meta-analysis. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e463.

- Wang, Y.; Long, Q.; Li, Y.; Kang, F.; Fan, Z.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, H.; Luo, Y.; Guo, R.; He, X.; et al. Mitigating magnesium deficiency for sustainable citrus production: A case study in Southwest China. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 295, 110832.

- Zhang, W.-W.; Wang, C.; Xue, R.; Wang, L.-J. Effects of salinity on the soil microbial community and soil fertility. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1360–1368.

- Rao, D.L.N. Microbiology of salt-affected soils. In Managing Salt-Affected Soils for Sustainable Agriculture; Minhas, P.S., Yadav, R.K., Sharma, P.C., Eds.; Indian Council of Agricultural Research: New Dehli, India, 2021; pp. 160–178.

- Kibria, M.G.; Hoque, A. A Review on Plant Responses to Soil Salinity and Amelioration Strategies. Open J. Soil Sci. 2019, 9, 219–231.

- Li, H.; Wang, B.; Siri, M.; Liu, C.; Feng, C.; Shao, X.; Liu, K. Calcium-modified biochar rather than original biochar decreases salinization indexes of saline-alkaline soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 74966–74976.

- Seesamut, T.; Ng, B.; Sutcharit, C.; Chanabun, R.; Panha, S. Responses to salinity in the littoral earthworm genus Pontodrilus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–10.

- Klouche, F.; Bendani, K.; Benamar, A.; Missoum, H.; Maliki, M.; Laredj, N. Electrokinetic restoration of local saline soil. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 22, 64–68.

- Li, X.; Zhang, C. Effect of natural and artificial afforestation reclamation on soil properties and vegetation in coastal saline silt soils. CATENA 2020, 198, 105066.

- Madani, A.; Hassanzadehdelouei, M.; Zrig, A.; Ul-Allah, S. Comparison of different priming methods of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) seeds in the early stages of growth in saline and sodic soils under irrigation with different water qualities. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 320, 112165.

- Mansour, M.M.F. Anthocyanins: Biotechnological targets for enhancing crop tolerance to salinity stress. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112182.

- Mishra, A.K.; Das, R.; Kerry, R.G.; Biswal, B.; Sinha, T.; Sharma, S.; Arora, P.; Kumar, M. Promising management strategies to improve crop sustainability and to amend soil salinity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 962581.

- Sagar, A.; Rai, S.; Ilyas, N.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Al-Turki, A.I.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Simarmata, T. Halotolerant Rhizobacteria for Salinity-Stress Mitigation: Diversity, Mechanisms and Molecular Approaches. Sustainability 2022, 14, 490.

- Fu, H.; Yang, Y. How Plants Tolerate Salt Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5914–5934.

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.-K.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of Plant Responses and Adaptation to Soil Salinity. Innovation 2020, 1, 100017.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant Responses and Tolerance to Salt Stress: Physiological and Molecular Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4810.

- Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants’ Response Mechanisms to Salinity Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2253.

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, P. Regulation of Plant Responses to Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4609.

- Ijaz, U.; Ahmed, T.; Rizwan, M.; Noman, M.; Shah, A.A.; Azeem, F.; Alharby, H.F.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Alharbi, B.M.; Ali, S. Rice straw based silicon nanoparticles improve morphological and nutrient profile of rice plants under salinity stress by triggering physiological and genetic repair mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107788.

- Ahmad, R.; Anjum, M.A. Physiological and molecular basis of salinity tolerance in fruit crops. In Fruit Crops, Diagnosis and Management of Nutrient Constraints; Srivastava, A.K., Hu, C., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 445–464.

- Wang, C.-F.; Han, G.-L.; Yang, Z.-R.; Li, Y.-X.; Wang, B.-S. Plant Salinity Sensors: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 859224.