Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 1 by Md. Aminul Islam.

Bangladesh derives one-half of its agricultural GDP and one-sixth of its national income from paddy. It is crucial to the farmers’ ability to survive. The majority of farmers in Bangladesh are classified as middle- or low-income. They must frequently take out loans to cultivate paddy. Moreover, they are compelled to sell their paddy at a lower price immediately after harvesting for primarily two reasons: the lack of storage facilities; and the immediate need for money to pay back loans taken out to buy labour, seeds, fertiliser, insecticides, and other necessities, and to fund daily costs.

- paddy

- sustainable paddy procurement system

- Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Agriculture is regarded as one of Bangladesh’s most important economic pillars. Agriculture’s contribution to the GDP is anticipated to reach 13.37 percent in 2018. It is diminishing daily. Bangladesh’s economy relies heavily on agriculture, which supports the majority of its population. According to BBS, the agriculture sector utilizes country’s 47% total labour force [1]. Primary macroeconomic objectives, such as poverty alleviation, employment generation, food security, and human resources development, impact this sector’s irresistible performance. Most farmers and their families wait eagerly for paddy harvesting all year round because all the family’s expenses depend on the paddy sale. Paddy is Bangladesh’s principal crop and the farmers’ financial lifeline. This country produces three varieties of rice: Aus, which is available during March to August; Aman, available between June to January; and Boro, available between November to May [2]. However, the current rice production narrative is only sometimes encouraging. Due to low prices, the experience of farmers engaged in paddy production can sometimes be depressing. Today, paddy production relies heavily on fertilisers, irrigation, and insecticides.

The majority of farmers in Bangladesh are classified as middle- or low-income. They must frequently take out loans to cultivate paddy. Moreover, they are compelled to sell their paddy at a lower price immediately after harvesting for primarily two reasons: the lack of storage facilities; and the immediate need for money to pay back loans taken out to buy labour, seeds, fertiliser, insecticides, and other necessities, and to fund daily costs. Wholesalers and millers in Faria, Bepari, Paiker, and Aratdar-cum regularly try to take advantage of farmers. Therefore, farmers are compelled to sell paddy at a relatively lower price during harvest. Paddy prices are usually unstable, and ironically, seasonal fluctuations have been common since the independence [2]. Due to paddy production in Bangladesh, the farmers suffer a lot. The sufferings of farmers who produce paddy are indeed numerous. Significantly, the government has launched many programs to boost the agricultural sectors, primarily to support the farmer [3,4][3][4].

To solve the issue of low paddy prices during harvest season, the government has adopted a highly effective step to buy paddy from farmers at a fair price. This procurement serves the dual aims of providing financial help to farmers and ensuring rice stockpiles for the Public Food Grain Distribution System (PFDS), especially when they are in a rush to sell it after harvest [3,5][3][5]. The government announces the procurement price at crop harvest, also known as the minimum support price, taking into account all elements relevant to paddy production in order for the producer to obtain the right price. Farmers generally anticipate that the purchase price will be higher than the cost of production. If the procurement price exceeds the production cost, farmers realise a profit and are motivated to cultivate paddy the following year [6]. Since the government declares the procurement price at harvest time each year, taking into account all factors relevant to the production of paddy, it is expected that the producers will receive a reasonable price for their paddy, which may be the minimum support price. Nevertheless, the middlemen, not the farmers, are getting accurate prices and taking the benefits. Its causes include a proper paddy procurement system, illiteracy, poor communication knowledge, poor communication system, insufficient communication infrastructure, and other farmer facilities.

Despite the government’s best efforts, the current paddy procurement system does not exist, real farmers are deprived of getting benefited instead, the benefits of support price go to the middlemen [7]. Not only are farmers deprived of the just price, but it also leads to an unstable food market, food price hiking, and ultimately food insecurity.

However, direct purchases of Aman, Boro, and Aus paddy from farmers grow daily, worsening farmers’ suffering. Lack of real-time information results in significant losses for farmers. Farmers in Bangladesh need a proper paddy procurement system, while intermediaries and other influential individuals involved in the paddy procurement system receive government benefits. As a result, paddy cultivation is discouraged among farmers. The situation is alarming for the nation’s food security and unemployment. This deficiency in paddy procurement system communication is extremely upsetting. Still, there is room for improvement in every aspect of procurement. There are few studies or research on farmers’ perceptions and levels of contentment with the current paddy procurement system in Bangladesh. Consequently, it is essential to understand the farmers’ mindsets to contribute to the actual development of Bangladesh.

Food is one of the most fundamental rights of the citizen of a country. The government should ensure food availability in the market all year round for its citizens. Market forces often consciously wait to exploit the food market and create artificial food crises. The consequences are widespread: price hiking, extra profit earning, and sometimes insufficient food supply. Thus, most of the time, similar in other countries, the government of Bangladesh faces the terrible need to buy and store paddy to ensure the available food supply in the market for its population for the whole year. Sometimes the government is bound to procure paddy or rice from the intermediary force of the market. The farmers and the government become hostage to the malevolent force. Even the blacklisted millers are so influential in their areas that the government sometimes has to depend on them. The millers purchase each kilogram of paddy at a reduced rate, pointing out the moisture percentage of the paddy.

Food is one of the most fundamental rights of the citizen of a country. The government should ensure food availability in the market all year round for its citizens. Market forces often consciously wait to exploit the food market and create artificial food crises. The consequences are widespread: price hiking, extra profit earning, and sometimes insufficient food supply. Thus, most of the time, similar in other countries, the government of Bangladesh faces the terrible need to buy and store paddy to ensure the available food supply in the market for its population for the whole year. Sometimes the government is bound to procure paddy or rice from the intermediary force of the market. The farmers and the government become hostage to the malevolent force. Even the blacklisted millers are so influential in their areas that the government sometimes has to depend on them. The millers purchase each kilogram of paddy at a reduced rate, pointing out the moisture percentage of the paddy.

2. Problems in Paddy Procurement System in Bangladesh

Rice is the most significant food crop in the world, feeding people more than any other crop. Nearly half the world’s population, more than 3 billion people, rely on rice daily. It is also the staple food across Asia, where around half of the world’s poorest people live, and is becoming increasingly important in Africa and Latin America. Rice has also fed people for longer than any other crop. It is spectacularly diverse, both in the way rice is grown and used by human beings. After harvesting, the rice grain undergoes several processes depending on how it will be used. These include drying, storing, milling, processing, and packaging—all before they are sold to markets. Rice has grown more abundantly than any other crop in the world. There are over 144 million rice farms worldwide, with a harvested area of about 158 million hectares [4]. About fifty percent of the world’s population subsists on rice. The Bangladeshi people eat this as their main food source. Rice provides a variety of dishes and culinary products, including Khai, Chira, Muri, various cakes, and many more. People can also enjoy Polao and Biryani, among many other rice-based dishes. Paddy is the primary source of nutrition for humans and animals, such as cows, and the paddy straw is also used to produce fertilisers. Therefore, numerous factors demonstrate that paddy cultivation is extremely important. According to Monthly Technology Today, paddy (rice) represents 35% of household expenditures in Bangladesh, making it the most significant staple food. Just the crop sector accounts for roughly 80% of Bangladesh’s agricultural output, with rice making up about 82%. Contribution of Rice to GDP, Guaranteeing Food Security and Generating Income The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics estimates that the contribution of agriculture to the GDP in 2018 will be 13.37 percent. Bangladesh’s economy is almost entirely dependent on agriculture, which employs 46% of the country’s total labour force and sustains the majority of its population [1]. According to rice millers, when they purchase paddy from farmers, its moisture content remains excessively high, increasing its weight. As a result, the paddy must be dried multiple times before husking. Last year, the government blacklisted 16,000 rice mills for purchasing paddy at a discount and hoarding vast paddy. Food Minister Qamrul Islam began purchasing rice and paddy from blacklisted millers on 15 April to meet the persistent rice shortage’s procurement demand [8]. Alam et al. [3] state, “The goals of local rice procurement are due to two factors: to grow rice stocks for the public food grain distribution system (PFDS) and to supply farmers with income support that is greater than the cost of production so that farmers do not produce at a loss and to achieve income support objectives”. However, researchers have demonstrated that the middlemen, not the farmers, reap the benefits due to the absence of a paddy procurement system. According to Sabur and others, the Bangladeshi government is persistently pursuing policies to achieve food self-sufficiency and improve the economic conditions of farmers [9]. According to Alam et al., Bangladesh’s food grain production meets domestic demand. The National Food Policy Plan of Action (2008–2015) is also responsible for PFDS’s efficacy. The paddy production and sales process in Bangladesh, the role of middlemen, the government’s policy, and how farmers can reap the actual benefits of paddy production are all described in detail. Distribution of paddy involves an excessive number of intermediaries, including commission agents, wholesalers, millers cum wholesalers, and retailers. Therefore, the price rises abnormally as a result of numerous middlemen taking the lion’s share of the profit [10]. In the current paddy procurement system, farmers are coerced into selling paddy by organised middlemen. To reach the goal, the government must eliminate the inherent flaws prevalent in agricultural marketing, including the presence of unnecessary middle city of market charges, a multiplicity of weights and measures, and market fraud [7]. In Bangladesh, the millers are the actual regulators of the rice market. Farmers Frias and Bepeparis sell paddy to packers, who then sell it to millers [11]. The millers are satisfied with the current paddy procurement system, but farmers feel that the paddy market needs to meet their needs [6]. The farmers, particularly the small- and medium-sized farmers, were insignificant, and it appeared that political elites primarily controlled procurement [9]. As a result of the farmers’ difficulties in selling their paddy, the government has taken effective measures to purchase paddy from the farmers at a price that supports them. As a result of the absence of a paddy procurement system, however, a number of researchers have demonstrated that it is the middlemen, not the farmers, who reap the benefits. Local rice procurement serves two purposes: constructing rice stocks for the public food grain distribution system (PFDS) and providing income support to farmers. As a result, production costs are increased to prevent farmers from incurring losses and meet income support objectives. It also supports producer prices effectively [3]. In earlier studies, several researchers worked on measuring the farmers’ satisfaction and awareness. Luo and Timothy investigated the farmers’ satisfaction towards land consolidation performance in China [12]. In addition, Kalyani tested the farmers’ awareness towards organic farming and found that 67% of the farmers have good perception towards organic farming [13].2.1. Government Paddy Procurement Procedure

The government buys paddy from farmers and rice from millers through its procurement centres throughout Bangladesh. There is an Officer in Charge (OC) and additional staff at each procurement centre. Each Upazila’s food procurement system is overseen by an Upazila Controller of Food (UCF), and each district’s food procurement system is under the control of a District Controller of Food (DCF). Based on the capacity of each procurement centre and the overall procurement target, the government sets the procurement target for each. A farmer can deliver paddy to the procurement centre for a base level of 70 kg and a maximum of 5 tonnes [4]. The government has made several changes to the procurement programme over the years to make it more practical, including listing farmers, increasing the targeted procurement quantity, and using a mobile app for procurement [14,15,16][14][15][16]. However, due to a need for more information and communication, farmers still require this program’s benefits, and intermediaries seize this opportunity [17].2.2. Private Sale-Open Market/Public Market

Paddy sale is necessary for the farmers immediately after harvesting, and the government procurement system commonly works later than harvesting time. The farmers are usually interested in selling their paddy to private sale centres or open markets rather than the government procurement system. Additionally, there are many other reasons for the farmers’ going to the private sale centres. First, there is a system of prompt cash transactions in the private market, and sometimes, it is in advanced payment; saving the transportation cost is one of the main reasons. Farmers can sell their paddy from a yard in a private sale system. In addition, in some cases, from the paddy field. During harvesting time, due to hurry and rough weather, it may be challenging to ensure the saleable quality of paddy, but in the procurement system, quality maintenance is necessary. Farmers can often sell their lower-quality paddy through a private sale system. In a private sale system, moisture and foreign particles are irrelevant to the paddy. “Farmers sell their paddy mostly to middlemen during the post-harvest period for practical reasons,” [9]. Paddy is traded via a number of middlemen, such as Kutial, Barkiwala, Faria, Bepari, and Miller. Kutial and Barkiwala need to have taken part in the purchasing process. The suppliers to the procurement centre are farmers and millers.2.3. Problems in Paddy Procurement System in Bangladesh

The current system for paddy procurement must be improved. Although most farmers and many individuals involved with the current paddy procurement system held divergent views, they all agreed that it must be revised. The current paddy procurement system still has room for improvement. According to some, the current procurement programme could provide incentives to farmers more effectively. There are many causes for this. The government purchases paddy from farmers and rice from millers in Bangladesh via paddy procurement centres. After harvest, farmers sell their rice primarily to middlemen for practical reasons. There are numerous types of middlemen involved in the rice trade. Kutial, Barkiwala, Faria, Bepari, and Miller are their names. Kutial and Barkiwala were both cut off from the purchasing process. The sole members of the procurement channel were Faria, Bepari, and Miller. The suppliers to the procurement centre are farmers or millers [9]. While the government has yet to start its procurement process, rice and paddy are being sold for less than the prices specified by the government. In the domestic food procurement programme, which the government had high hopes for when it declared at the beginning of harvest season that it would buy a larger amount of paddy directly from farmers. Yet, thousands of Boro farmers are still at the mercy of private buyers and middlemen two weeks after the official opening of the paddy and rice procurement campaign on 5 May [8]. In comparison to what the government provided through the public procurement programme, the farmers provide substantially less to the middlemen. Farmers are suffering since the government’s drive to purchase rice has not yet started [8]. Organised middlemen push farmers into selling paddy under the current paddy procurement system. Hence, in order to achieve the goal, the government should do away with the fundamental problems that currently exist in agricultural marketing, such as the use of pointless middlemen, a proliferation of market fees, a proliferation of weights and measures, and market fraud. To ensure a fair pricing process, the government must also be aware of the effects of a strong marketing system [7]. Farmer Afsar Ali lives in the Aditmari village in Lalmonirhat. He believes that his price of Tk 12 per kilogramme for harvested Boro is below the cost of production. When the government announced that it would buy paddy for Tk 23 per kilogramme, farmers in the same district, such as Abdul Gafur, were overjoyed. However, they do not know when to sell rice in government silos [8]. The millers are the ones that control the paddy market in Bangladesh, according to Robel’s research. He gives an example of the channels being preserved. Faria, Bepari, Paiker, and Aratdar-cum are the middlemen or intermediaries in marketing networks [11]. Millers are given as much paddy as they need, but farmers must still be paid fairly. Thus, millers are satisfied with the current paddy procurement system, but from the farmers’ point of view, the paddy market needs to fulfil its purpose [6]. As the farmers have to sell the paddy during harvesting time, they have to face means. Different intermediary groups or agencies try to exploit the farmers. Throughout distribution, the paddy sales go via far too many middlemen, including commission agents, wholesalers, millers, and cum wholesalers. When so many intermediaries are taking the lion’s share of the profit, the price increases excessively. The government should maintain a sound food policy that keeps the price consistently under control and keeps good food stock in order to ensure that the public distribution system has enough rice and to prevent middlemen from making a profit. Bangladesh farmers’ experience significant losses with their produce each year as a result of a lack of storage facilities and a government that cannot effectively regulate the market. Governmental initiatives were unsuccessful. The millers pay farmers far less for paddy than the set price set by the government [18]. The standard procurement system and current procurement system are given below in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

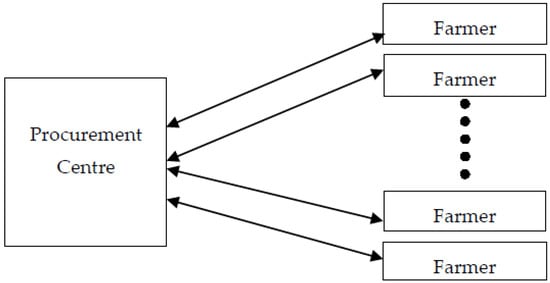

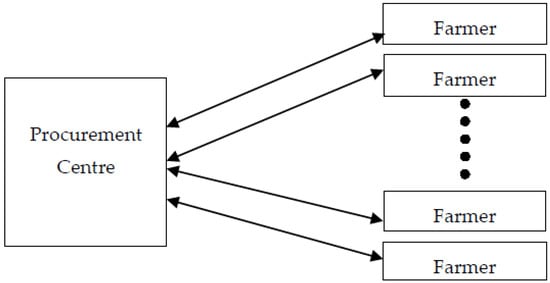

Figure 1.

Standard Paddy Procurement System.

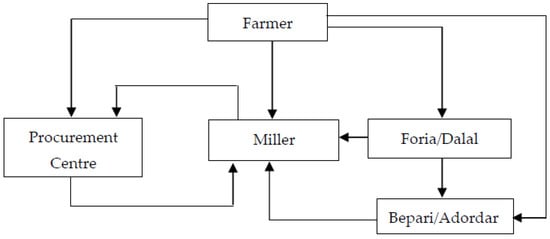

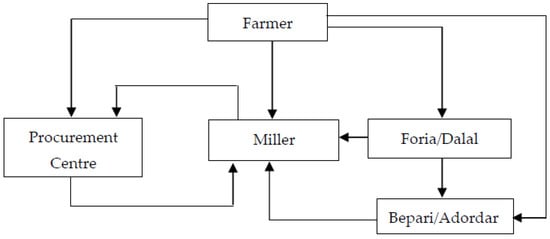

Figure 2.

Current paddy Procurement System.

References

- BBS. Statistical Pocketbook Bangladesh 2018; Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018.

- Chowdhury, N. Seasonality of food grain price and procurement program in Bangladesh science liberation: An exploratory study. Bangladesh Dev. Stud. 1987, 15, 105–128.

- Alam, M.J.; Akter, S.; Begum, I.A. Bangladesh’s Rice Procurement System and Possible Alternatives in Supporting Farmers’ Income and Sustaining Production Incentives; A Study Report; Department of Agribusiness and Marketing, Bangladesh Agriculture University: Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2014.

- Islam, M.A. Review of Literature and Development of Models Relating to the Application of ICT in Paddy Procurement System in Bangladesh. Int. J. Ethics Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 43–57.

- Islam, M.A. Current Paddy Procurement System and Supporting Farmers in Selective Areas of Bangladesh: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Ethics Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 55–73.

- Raha, S.K.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Alam, M.M.; Awal, M.A. Structure, Conduct, and Performance of the Rice Market and the Impact of Technological Changes in Milling; Research Report; Institute of Agribusiness and Development Studies, Bangladesh Agriculture University: Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2013.

- Dewan, M.F.A. A Study on Rice Marketing System in Bangladesh with Time Series and Cross-Sectional Data. Master’s Thesis, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2011.

- Ahmad, R. Boro farmers at the mercy of middlemen: Buyers offer prices lower than govt-fixed rates for paddy, and rice; procurement by govt yet to start. The Daily Star, 1 May 2016; p. 2.

- Sabur, S.A.; Jahan, H.; Reza, M.S. An evaluation of the government rice procurement program in selected areas of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 26, 111–126.

- Prakash, C. Problems and expectations of the farmers in marketing paddy in Tiruvarur district, Tamilnadu. Asian J. Manag. Res. 2012, 3, 253–262.

- Robel, M. Marketing of Boro Paddy in a Selected Area of Netrakona District. Master’s Thesis, Bangladesh Agriculture University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2013.

- Luo, W.; Timothy, D.J. An assessment of farmers’ satisfaction with land consolidation performance in China. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 501–510.

- Kalyani, V. Perception of Farmers towards Organic Farming: A Glace of Agricultural Perspective. SSRN 2021, 3879917. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3879917 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Roy, A.C.; Rahman, M.A.; Khan, M.A. Yield gap, profitability, and inefficiency of Aman rice in coastal areas of Bangladesh. Progress. Agric. 2020, 30, 395–404.

- Amin, M.A. Government Procurement of Rice through App Delayed, Limited. Dhaka Tribune. 2020. Available online: https://www.dhakatribune.com/Bangladesh/government-affairs/2020/04/29/government-procurement-of-rice-through-app-delayed-limited (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Parvez, S. Govt to Buy 50pc More Paddy to Feed the Poor. The Daily Star. 2020. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/govt-buy-50pcmore-paddy-feed-the-poor-1890667 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Zahid, S.H. Paddy Procurement: Intention and Outcome. 2020. The Financial Express. Available online: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/paddy-procurement-intention-and-outcome-158402999 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Rubaiyat, M.Q.I.; Roy, S.D.; Shakil, M. A country of famished farmers. The Daily Star Weekend, 4 May 2018; p. 35.

More