2. Pathogenesis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Abbreviated Summary)

The primary pathogens in VVC are

Candida species, likely originating from the gastrointestinal tract and achieving initial asymptomatic vaginal colonization as commensals.

Candida microorganisms enjoy a saprophytic existence in a moderated non-adversarial environment created by vagino-protective microbiota. In particular, organic acids, both acetic and lactic acid, contribute to vaginal tolerance of

Candida spp.

[5]. The presence of a tolerant cytokine atmosphere emphasizes the critical role of the vaginal mucosa and its expressed defensive function

[2][3][4][2,3,4]. The local effect of estrogen plays a dominant role in the healthy lower genital tract microbiome in allowing

Candida commensalism. Vaginal yeast colonization can be long term and is influenced by host genetic influences together with acquired colonizing promoting factors, both behavioral and biologic

[3][4][3,4]. The outcome of benign asymptomatic colonization as well as

Candida vaginitis reflects the interplay of three factors: yeast, vaginal microbiota, and host mucosal immune factors. A detailed description of human vaginal mucosa, host immunity, and the role of vaginal microbiota in the pathogenesis of VVC has been reviewed by several investigators

[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. A critical role of host local innate immunity, in both defense and pathogenesis of VVC, is widely proposed with resultant symptoms and signs the consequence of host no-longer protective inflammatory response

[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Acute symptomatic

Candida vulvovaginitis represents a dramatic change triggered by multiple factors but always requiring prior vaginal yeast colonization and characterized by proliferation of yeast blastospores and hyphae formation with expression of multiple fungal virulence factors, and these microbiome changes result in superficial vaginal epithelial surface invasion and consequent vaginal epithelial cell proinflammatory reaction. The accompanying myriad signs and symptoms evident in acute vulvovaginitis soon follow. Both IL-1β and IL-6 are increased as part of the proinflammatory mucosal response

[3][4][7][8][3,4,7,8]. Risk factors for acute VVC include vaginal dysbiosis after antimicrobials, increased estrogen, and uncontrolled diabetes, all superimposed upon genetic susceptibility consisting largely of single nucleotide polymorphisms

[3][15][3,15]. All members of the triad contribute to the risk and expression of disease. VVC may be acute, short-lived, chronic, or recurrent. Unlike oral candidiasis, immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for VVC.

3. Pathogenesis of Bacterial Vaginosis (Abbreviated Summary)

Unlike VVC, with a single or mono-pathogen pathogenesis, BV represents a severe polymicrobial vaginal dysbiosis with loss or disappearance of what is considered “healthy” protective

Lactobacillus species and overgrowth of multiple largely strict anaerobic and facultative species, creating a more diverse bacterial abundance. This includes multiple

G. vaginalis species,

Fannyhessea vaginae,

Mobiluncus spp., and BVAB (BV-associated bacteria 1–3) and

Bacteroides spp.,

Clostridiale spp.,

Prevotella spp.,

Zozaya spp., and others

[16][17][16,17]. Whether the overgrowth of these pathogenic species contributes to the reduction or elimination of

Lactobacillus species or alternatively follows their disappearance has not been conclusively established. Many investigators favor the introduction or emergence of the pathologic consortium of anaerobes as the primary process, possibly related to sexual transmission from a male or female partner

[18]. Some virulent

Gardnerella spp. are thought to be a key factor in BV pathogenesis, displacing vaginal

Lactobacillus spp. and adhering to vaginal epithelial cells. Considerable evidence indicates the role of sexual transmission to explain multiple recurring BV episodes in women followed longitudinally, although sexual transmission or pathogen reintroduction is clearly not the only mechanism of frequent recurrence or relapses

[19].

More recently, the recognition and appreciation of the BV biofilm coating the surface of the vaginal mucosa has contributed to understanding the pathogenesis of BV, especially RBV, and has improved treatment of BV. Virulent strains of

Gardnerella spp. are thought to initiate biofilm production and are often the predominant species present in the biofilm

[19]. It is hypothesized that certain

Gardnerella species act to lower the oxidation reduction potential of the vaginal micro-environment as well as elaborating essential substrates (NH

3), allowing growth of strict anaerobic bacteria. The microbiome of BV has undergone extensive investigation in the last decade, significantly enhanced by the availability of PCR and next-generation sequencing, leading to advances in diagnosis, but it has not, to date, contributed to treatment advantage

[20][21][22][23][20,21,22,23]. A conceptual model of BV pathogenesis including initial invasion with

G. vaginalis and

Prevotella bivia, followed by a second wave of colonizers including

Atopobium vaginae and

Sneathia spp., has been proposed

[23].

Turning to the third component of the causal triad, the role of the host immune system in the pathogenesis of BV and expressed in the vaginal mucosa has been extensively investigated. BV has long been considered a “non-inflammatory” condition, hence the term “vaginosis” and not “vaginitis”

[24]. This early definition or designation was largely driven by lack of typical clinical signs of vaginal and vulvar inflammation including pain, soreness, or dyspareunia. This decision was reinforced by the striking absence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in the vaginal exudate or discharge on saline microscopy. However, this assumption did not match later immunologic scrutiny. The vaginal environment in BV is profoundly proinflammatory, as confirmed in multiple studies

[20][25][26][27][20,25,26,27]. Cytokine and chemokine increase are evident with increase in IL-2, type 1 interferon. The lack of PMNs appropriately reflects the effect of chemokine or chemotaxic inhibitors preventing their accumulation. The role of vaginal inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of BV is largely unknown and is perhaps crucial to the loss of protective

Lactobacillus species as well as to explaining clinical BV recurrence and resistance to probiotic therapy.

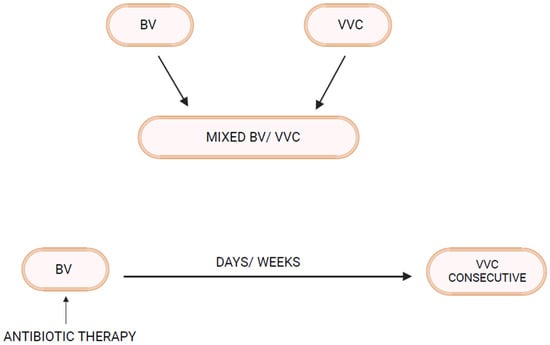

4. Linking BV and VVC

As mentioned above, not all women with RVVC have associated BV or RBV. In fact, many women with RVVC have no such association. On the other hand, in some women prone to RBV, clinical experience reveals that RVVC is an enormous and predictable additional problem

[28]. Invariably, it is BV that precedes and appears to trigger RVVC episodes. The first question to be addressed is whether vaginal

Candida colonization rates are increased in women with BV. In fact, several vaginal microbiota studies in women with BV reveal increased rates of

Candida vaginal colonization

[28]. Similarly,

Candida colonization rates in

theour clinic in women with acute BV, even in the absence of positive microscopy for yeast elements, are approximately 30–35%, significantly higher than in matched women serving as normal controls (12–15%). This is not surprising given the higher vaginal pH characteristic of BV reflecting loss of lactic acid and bacteriocin-producing protective

Lactobacillus species. This is particularly evident in

L. iners-dominant communities characteristic of BV, both during acute attacks of symptomatic BV as well as following successful treatment of BV with metronidazole

[29][30][29,30]. As a general principle, therefore, vaginal dysbiosis facilitates

Candida colonization

[2][6][2,6].