Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Azizur Rahman and Version 1 by Azizur Rahman.

Organic agriculture has gained more popularity, yet its approach to food production and its potential impact on consumers’ health and various environmental aspects remain to be fully discovered. The goal of organic farming practices is to maintain soil health, sustain ecological systems, maintain fairness in its relationship with the environment and protect the environment in its entirety. Various health benefits have been associated with higher consumption of organic foods.

- organic foods

- food safety

- obesity

- cancer

- food security

1. Introduction

Organic farming is designed to mitigate environmental pollution and prioritize animal welfare through protective management strategies that prevent exposure to harmful pesticides, industrial solvents and synthetic chemicals [1,2][1][2]. However, this system of management goes beyond avoiding the use of synthetic inputs by basing its practices on four principles: health, ecology, fairness and care [3,4][3][4]. The principle of health ensures that organic agriculture should sustain and strengthen the health of the soil, plants, animals, humans and the earth as a whole [3]. The principle of ecology focuses on living ecological systems and how organic agriculture should work with, sustain and emulate these systems [3,5][3][5]. The principle of fairness underscores the importance of relationships ensuring fairness in the common environment and life opportunities [3]. Finally, the principle of care advocates for safe and responsible agricultural management to protect current and future generations and the environment [3]. To adhere to these principles, organic farming employs practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, polyculture, covering crops, seeding timing and mulching [3]. Notably, the increasing awareness and demand for organic food in recent years are attributed to its perceived health benefits and positive impact on environmental biodiversity [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15].

The primary motivation for purchasing organic food is its perceived health benefits, followed by considerations for ecosystems and the environment [11,12,13,14,15,16,17][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]. Consequently, the global organic food market has experienced rapid growth, with an estimated 10% increase since 2000 [18]. Since then, the organic food production market was valued at CAD 7 billion in 2020 and organic packaged food sales are projected to reach USD 1.6 billion by 2025 [19]. Considering the rapidly growing demand for healthy, environmentally conscious foods, it is important to explain how public perception of the organic diet has influenced its surge in popularity.

Generally, several reports have uncovered that consumers who strictly follow an organic diet do so for one of several reasons: perceived health benefits, concern for the environment and the inherent value of buying local [11,15,16,17,19,20][11][15][16][17][19][20]. Health-conscious consumers are more likely to avoid mainstream products containing pesticides, hormones, and other additives, instead opting for organic alternatives that are marketed as natural and chemical-free [15,16][15][16]. Correspondingly, Rana and Paul discovered that Canadians placed a lot of value on the certification and labeling of the organic packaged goods they were buying [21]. Comparatively, concerns about accessibility, safety, and price were predominant in Slovenia, Portugal and China [21]. Some Canadian organic consumers even had preferences for particular organic certificates and commonly sought information about the product’s origins and the production methods used [21]. Thus, consumer trust in the product they are purchasing heavily influences their decision to buy organic [11,12,13,15,19,20,21][11][12][13][15][19][20][21].

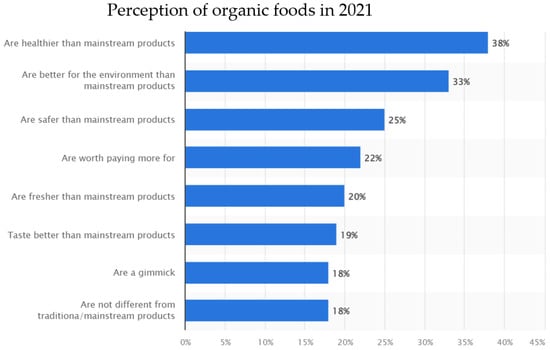

Conversely, the higher cost, lack of widespread availability and lack of perceived value were all reported to be factors that deterred consumers from purchasing organic foods [15,19,20,21][15][19][20][21]. Previous studies have discovered that organic foods are on average 10% to 40% more expensive than conventionally produced foods [22]. Further on, a 2021 online survey of up to 187,000 Canadians demonstrated that 18% of respondents believed organic foods were no different from mainstream products [19], possibly because the evidence surrounding their health benefits remains ambiguous.

Considering affordability and perceived value majorly influence purchasing decisions, higher income levels often correlate with an increased likelihood of purchasing organic foods [13,21,22][13][21][22]. In addition, higher levels of education are associated with greater awareness of health and environmental concerns related to food choices [13]. Educated consumers may be more informed about the benefits of organic farming practices and choose organic products accordingly. A recent study investigating the organic purchasing intentions of Bangladeshi consumers uncovered a significant positive correlation between the level of education and the intention to purchase sustainable organic food. Specifically, the study found a 3.27-fold increase in organic food purchasing among consumers with higher levels of education [13]. Other socio-economic factors that may influence organic purchasing decisions include age and gender, cultural dietary habits and health and wellness trends in the market [11,12,13,14,15,16,20,21][11][12][13][14][15][16][20][21]. For example, the same study demonstrated that Hungarians and Swiss people over the age of fifty are more price sensitive [13]. In addition, some cultural or ethnic groups may have traditions or preferences for specific types of organic produce or traditional farming methods, such that individuals with specific health concerns or dietary preferences may opt for organic options. Finally, growing health consciousness and a focus on wellness can drive the demand for organic foods perceived as healthier and free from synthetic chemicals [13,14,15][13][14][15]. Figure 1, taken from Statista 2021 [19], further breaks down the surveyed consumers’ attitudes toward organic products and provides further insights into how organic food is perceived in Canada.

Figure 1. Breakdown of opinions on organic food in Canada. Data collected from a 2021 online survey of up to 187,000 Canadians over 18 years of age.

2. Organic versus Conventional Food

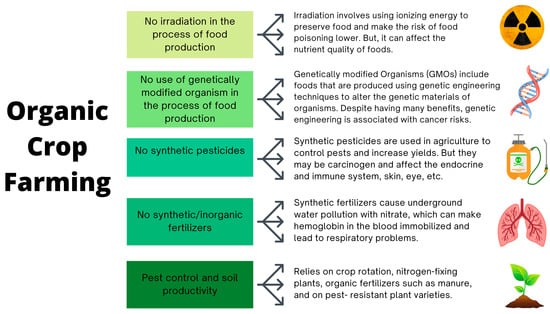

The production of organic food requires special considerations (Figure 2). Generally, organic farming is solely grounded in biological and ecological processes that mitigate the environmental impact of agricultural practices while preserving the natural qualities of food [10,24][10][23]. In this holistic approach, pest and disease control are achieved naturally, eliminating the need for synthetic chemicals utilized in conventional farming [24,25][23][24]. Additionally, organic food must not be sourced from genetically modified organisms (GMOs) [24,26][23][25]. Organic farming also relies on mechanical weeding as an alternative to traditional herbicide input, potentially leading to increased weed cover that benefits various organisms by promoting biodiversity [26][25]. Core principles of organic agriculture, such as the use of green manure, crop diversification, and small fields, further contribute to the production system’s sustainability [26][25]. Following these principles, organic farming is believed to enhance soil fertility and foster biodiversity. Studies indicate that local species richness and abundance can increase by approximately 34% and 50%, respectively, across various crops worldwide compared to conventional farming practices [26][25]. Thus, there has been a recent upsurge in both the production and purchasing of organic goods, driven by a heightened demand for natural products that undergo minimal processing and abstain from synthetic and artificial fertilizers or pesticides in their production processes [27,28][26][27].

Figure 2. Organic crop farming at a glance.

Unlike conventional farming, organic farming does not use genetic engineering or synthetic pesticides in the food production process, allowing for an assessment of their health effects. The use of genetic engineering and GMOs can pose various health risks, such as allergic reactions and unexpected interlinks between genes due to gene additions and modifications [31][28]. Moreover, pesticides utilized in agriculture can accumulate in soil and water, quickly entering the food chain and impacting human health [32][29]. These health effects span from allergic reactions to lung damage, causing breathing difficulties, nervous system problems, birth defects, and the risk of chronic diseases such as cancer [32][29]. For instance, the organochlorine insecticide (OCI) dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) functions by opening sodium channels in the human nervous system, leading to increased firing of action potentials that can result in spasms and, in severe cases, death [34,35][30][31]. Conversely, carbamate insecticides inhibit the acetylcholinesterase enzyme, interfering with cell replication and differentiation, proper synapse signaling, and other neurotoxic effects [34,36][30][32]. Furthermore, the growth regulator herbicide 2,4-D, used to eliminate weeds, has been linked to severe eye irritations and fertility problems in men [34][30]. Studies have also associated anilide/aniline herbicides with risks of colon and rectal cancer [34][30]. Glyphosate, a common ingredient in pesticides found in GM crops, has also been linked to cancer risks, especially non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [31][28]. Glyphosate was first used as a broad-spectrum pesticide in 1974 [37][33]. As genetically engineered glyphosate-tolerant crops were introduced, glyphosate quickly spread worldwide and has now become the most widely used pesticide in agricultural and residential sectors [37][33]. However, glyphosate is an organophosphorus compound which interferes with aromatic amino acid synthesis through a mechanism unique to plants [37][33]. Thus, concerns have arisen about glyphosate’s potential genotoxicity through the induction of oxidative stress for human cells in vitro and in animal experiments [37][33].

It is important to note that a majority of these experiments tested much higher doses than those permitted for agricultural use. Notably, esteemed institutions such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have affirmed glyphosate’s status as non-toxic and non-carcinogenic to human target organs as of 2022 [38][34]. In rabbit studies conducted by the EFSA, an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 0.5 mg/kg of body weight per day was defined, while the FAO and WHO established an acute toxicity measure (LD50) of 5600 mg/kg of body weight for the oral pathway and over 2000 mg/kg of body weight for the dermal pathway [38][34]. Consequently, the commercialization of glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) is subject to stringent regulations, including the establishment of maximum residue limits (MRLs) for glyphosate residues in various food items.

Considering the MRL for pesticides is typically determined through testing individual pesticides on rats for a relatively brief duration, there is a substantial lack of knowledge regarding the consequences of consuming potentially hundreds of different pesticides over one’s lifetime. The intricate interplay of these various pesticides remains largely unknown. Thus, further research is needed to uncover the cumulative long-term health effects of glyphosate and other pesticide residues, as many studies reveal a variety of toxic effects [38][34]. As a result, pesticide use may adversely affect human cells through mechanisms still unclear, and it may be possible to minimize these health risks by re-orienting agricultural practices toward more organic approaches.

2.1. Nutritional Benefits

The nutrient and mineral content of crops is affected by various agronomic factors including fertilization type, crop rotation designs and crop protection protocols [24,39][23][35]. For example, the addition of organic matter to soil helps provide food for beneficial plant microorganisms, and in return, these stimulated microorganisms produce valuable compounds (including citrate and lactate) that make soil minerals more available to organic plant roots [39][35]. In addition, organic farming allows for the slow release of soil minerals over time, causing essential nutrients to become available when needed, whereas chemical fertilizers quickly dissolve in irrigation water and deliver excess quantities of nutrients to crops, often past what is needed [39][35]. Thus, agronomic differences in organic versus conventional farming systems may impact the quantity and quality of beneficial compounds that can be obtained from each crop type [24,39][23][35]. However, studies comparing the nutrient content between organic and conventional crops have revealed inconsistent results [24][23]. Further on, many of these studies lack the necessary control factors to validate the results, such as failing to consider the different environmental and growing conditions that affect crop quality [24][23]. In 2012, Smith-Spangler et al. [29][36] reviewed the results of 223 studies examining the nutrient content of organic foods, including ascorbic acid, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, iron and various vitamins. The findings showed that organic fruits, vegetables, and grains do not exhibit significantly higher nutrient levels compared with their non-organic counterparts. However, organic produce did show higher levels of phosphorus when compared with non-organic produce [29][36]. All in all, the evidence was not strong enough to suggest that organic foods are more nutritious than non-organic foods. However, further recent experiments [40,41,42,43][37][38][39][40] have demonstrated that some organic foods, such as corn grain, wheat flour, broccoli, tomato, black sesame and leafy vegetables, contain more minerals and vitamins, which are discussed below.

2.2. Mineral Content

The most essential minerals are calcium, magnesium, potassium, iron, zinc, copper, manganese, selenium and iodine [40][37]. Studies have shown that the content of these minerals in fruits, especially apples, does not differ significantly between organically grown and conventional methods [40,41][37][38]. Studies on organic vegetables, however, revealed higher levels of iron and magnesium compared to conventionally grown vegetables. Overall, Worthington revealed that the iron and magnesium content in organic crops was higher by 21% and 29%, respectively [39][35]. Moreover, a study by Yu et al. [42][39] demonstrated 20% higher magnesium content and 30% higher phosphorus and potassium contents in organic compared to conventionally grown summer corn. However, the study did not provide details on methodologies or sample sizes, thereby limiting the credibility of the reported data. They also found higher levels of zinc and iron in organic corn, but this increase was not significant [42][39]. These findings were further compounded by Rembialkowska [43][40], where the results of many experiments demonstrated a higher level of iron, phosphorous and magnesium content in organically grown compared to non-organically grown products. These results may be attributed to the effects of traditional potassium fertilizers used in conventional agriculture, which can decrease the amount of magnesium—and consequently, phosphorus—absorbed from soils [39][35]. Further on, organic fertilizers tend to increase the number of soil microorganisms that affect various components of plant nutrient acquisition and metabolism, which may play an essential role in making iron more bioavailable to plant roots [39][35]. Confounding factors, including variations in soil fertility, pH levels and the presence of specific minerals across different plots and geographical regions, can significantly influence the absorption and availability of nutrients for plants [39][35]. Consequently, any observed differences in the nutritional content of organic and conventional produce may be attributed to variations in soil conditions and cultivation practices rather than the farming methods alone. To mitigate these potential confounding variables, researchers must meticulously control and monitor soil conditions, cultivation practices and climatic variations in their study to ensure that the comparison between organic and conventional crops is not influenced by any disparities in these factors.

2.3. Vitamin Content

Experiments on the various vitamin contents of different organic versus non-organic fruits and vegetables are limited. A 2010 review on the nutritional quality of organic food revealed higher vitamin C contents in organic potatoes, tomatoes, kale and celeriac as well as higher vitamin E content in organic olive oil [40][37]. Similarly, Worthington’s experiment revealed 27% higher vitamin C levels in organically grown lettuce, spinach, potatoes and cabbage [39][35]. On the other hand, some studies on beta-carotene (vitamin A precursor) have shown that the beta-carotene content of organic foods greatly depends on the type of fertilizer used, as nitrogen fertilizers have been shown to yield higher beta-carotene levels in carrots [40,41][37][38]. Other experiments have shown similar outcomes in conventional agriculture, such that increased fertilization changes the content of secondary plant metabolites [44][41]. For example, Mozafar [45][42] revealed that nitrogen fertilizer used in conventional fruits and vegetables could increase the amount of beta-carotene and reduce vitamin C levels. This phenomenon can be attributed to alterations in plant metabolism observed in response to the differences between organic and conventional fertilizers. For example, when exposed to a high influx of nitrogen, plants tend to increase protein production while diminishing carbohydrate production, ultimately leading to a reduction in vitamin C synthesis [39][35]. Consequently, the vitamin content in crops is significantly influenced by the specific agronomic factors associated with each farming system.

2.4. Other Compounds

Oxidation of phenolic compounds by the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzyme is part of the plant antioxidant defense mechanism (to repair injuries on their surface). Phenolic compounds act as a chemical barrier against invading pathogens. Intact antioxidant defense in plants has been shown to have important implications for human health, including playing an anticarcinogenic role [42][39]. Organic cultivation operations have been revealed to increase the polyphenol content of peaches and pears as compared with their conventional counterparts [9]. Moreover, increased activity of the PPO enzyme towards chlorogenic and caffeic acids (antioxidant agents) was observed to be notably higher in the organic samples of peaches and pears [9]. Overall, various studies on organic crops have observed between 18% and 69% increased antioxidant activity in these products [46][43]. Intake of antioxidants and phenolic compounds from food consumption is important because these compounds have been shown to effectively reduce the risk of chronic diseases, including some neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases and cancer [46][43].

Importantly, organic foods also demonstrated lower levels of toxic metabolites, such as cadmium and pesticide residues [49][44]. Cadmium is a heavy metal that is known to accumulate in the body and exert toxic effects on the kidneys and liver [49][44]. Importantly, eight meta-analyses conducted by Barański et al. revealed that organic crops contained on average 48% lower cadmium concentrations than conventional crops [49][44]. Further on, the frequency of detectable pesticide residues was four times lower in organic crops, whereas the frequency of phenolic (antioxidant) compounds was on average 20–40% and, in some cases, over 60% higher in organic crops [49][44]. The study analyzed a comprehensive dataset comprising 343 peer-reviewed publications, where notable discrepancies emerged across different crop types, crop species, and studies conducted in countries with different climates, soil types and agronomic backgrounds. Thus, potential limitations of these meta-analyses include variations in study methodologies and geographical locations that confound the observed results. However, by employing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessments, Development, and Evaluation) assessment to gauge the strength of evidence for a standard weighted meta-analysis, the overall strength of evidence was deemed moderate or high for the majority of parameters where significant differences were identified (i.e., many phenolic compounds, cadmium and pesticide residues) [49][44].

Accordingly, a French BioNutriNet case-control study investigated the difference in urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations between 150 high-organic-food consumers and 150 low-organic-food consumers, matched for dietary patterns and other relevant traits [50][45]. Notably, the authors saw significant reductions of organophosphrous pesticides (OPs), diethyl-thiophosphates, dimethylthiophosphase, dialkylphosphates (DAPs) and free 3-phenoxybenzoic acid in the high-organic-consumer group, ranging from –17% to –55% reductions compared to the low-consumption group [50][45]. These differences were attributed to fertilization techniques, crop protection regimens, and other agronomic factors between growing practices. For example, organic farming systems avoid the use of fertilizers produced from industrial waste, which are often the most contaminated by toxic heavy metals [39][35].

3. Impact on Human Health

The findings from clinical experiments assessing the health impact of organic food on humans are relatively limited compared to other nutritional epidemiological studies. Many of these experiments are short term and may be confounded by variations in dietary patterns and lifestyles that profoundly affect human health [51][46]. Notably, observational studies often lack a comprehensive examination of the various health factors that may differ between organic and non-organic food consumers, such as lifestyle choices, physical activity levels and overall dietary patterns [50,51][45][46]. These factors may be a source of confounding that significantly influence the health outcomes observed, precipitating the need for further longitudinal intervention studies. Nevertheless, the compounds found in organic fruits and vegetables are generally believed to promote human health and longevity [51][46]. Consequently, individuals who consistently consume organic food often opt for more fruits and vegetables and less meat, potentially reducing the risk of mortality and chronic diseases [52,53,54,55,56,57][47][48][49][50][51][52]. Additionally, research indicates that those who regularly choose organic food are more likely to be female, have higher education and income levels and maintain a healthier lifestyle by smoking less and engaging in more physical activity [50,51,58,59][45][46][53][54]. As a result, the dietary compositions of organic and non-organic consumers may significantly differ.

References

- Hsu, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, T.T. An Analysis of Purchase Intentions toward Organic Food on Health Consciousness and Food Safety with/under Structural Equation Modeling. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 200–216.

- Muneret, L.; Mitchell, M.; Seufert, V.; Aviron, S.; Djoudi, E.A.; Pétillon, J.; Plantegenest, M.; Thiéry, D.; Rusch, A. Evidence That Organic Farming Promotes Pest Control. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 361–368.

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental Impact of Different Agricultural Management Practices: Conventional vs. Organic Agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 95–124.

- Brantsæter, A.L.; Ydersbond, T.A.; Hoppin, J.A.; Haugen, M.; Meltzer, H.M. Organic Food in the Diet: Exposure and Health Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 295–313.

- Migliorini, P.; Wezel, A. Converging and Diverging Principles and Practices of Organic Agriculture Regulations and Agroecology. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 63.

- Hurtado-Barroso, S.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Organic Food and the Impact on Human Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 704–714.

- Brandt, K.; Mølgaard, J.P. Organic Agriculture: Does It Enhance or Reduce the Nutritional Value of Plant Foods?: Nutritional Value of Organic Plants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 924–931.

- Woese, K.; Lange, D.; Boess, C.; Bögl, K.W. A Comparison of Organically and Conventionally Grown Foods—Results of a Review of the Relevant Literature. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997, 74, 281–293.

- Carbonaro, M.; Mattera, M.; Nicoli, S.; Bergamo, P.; Cappelloni, M. Modulation of Antioxidant Compounds in Organic vs. Conventional Fruit (Peach, Prunus persica L., and Pear, Pyrus communis L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5458–5462.

- Giampieri, F.; Mazzoni, L.; Cianciosi, D.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Regolo, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Capocasa, F.; Xiao, J.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Organic vs. Conventional Plant-Based Foods: A Review. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132352.

- Curvelo, I.C.G.; Watanabe, E.A.d.M.; Alfinito, S. Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. REGE 2019, 26, 198–211.

- Singh, A.; Glińska-Neweś, A. Modeling the public attitude towards organic foods: A big data and text mining approach. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 2.

- Akter, S.; Ali, S.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Fogarassy, C.; Lakner, Z. Why Organic Food? Factors Influence the Organic Food Purchase Intension in an Emerging Country (Study from Northern Part of Bangladesh). Resources 2023, 12, 5.

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058.

- Gundala, R.R.; Singh, A. What motivates consumers to buy organic foods? Results of an empirical study in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257288.

- Hamzaoui Essoussi, L.; Zahaf, M. Exploring the Decision-making Process of Canadian Organic Food Consumers: Motivations and Trust Issues. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2009, 12, 443–459.

- Boobalan, K.; Nachimuthu, G.S. Organic Consumerism: A Comparison between India and the USA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101988.

- Załęcka, A.; Bügel, S.; Paoletti, F.; Kahl, J.; Bonanno, A.; Dostalova, A.; Rahmann, G. The Influence of Organic Production on Food Quality—Research Findings, Gaps and Future Challenges: Influence of Organic Production on Food Quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2600–2604.

- Shahbandeh, M. Consumer Perspective of Natural and Organic Food and Drink in Canada in 2021. Statista. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1281346/natural-and-organic-food-consumer-perspective-canada/ (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Shahbandeh, M. Organic Food Market in Canada—Statistics & Facts. Statista. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/4235/organic-food-market-in-canada/#topicOverview (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 44, 162–171.

- Forman, J.L.; Silverstein, J.; Committee on Nutrition; Council on Environmental Health; American Academy of Pediatrics. Organic foods: Health and environmental advantages and disadvantages. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1406–e1415.

- Suciu, N.A.; Ferrari, F.; Trevisan, M. Organic and Conventional Food: Comparison and Future Research. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 49–51.

- Glibowski, P. Organic Food and Health. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2020, 71, 131–136.

- Tscharntke, T.; Grass, I.; Wanger, T.C.; Westphal, C.; Batáry, P. Beyond Organic Farming—Harnessing Biodiversity-Friendly Landscapes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 919–930.

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Foodomics: A New Tool to Differentiate between Organic and Conventional Foods: General. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 1784–1794.

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Occurrence of Environmental Pollutants in Foodstuffs: A Review of Organic vs. Conventional Food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 370–375.

- Hug, K. Genetically Modified Organisms: Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks? Medicina 2008, 44, 87.

- Schrama, M.; de Haan, J.J.; Kroonen, M.; Verstegen, H.; Van der Putten, W.H. Crop Yield Gap and Stability in Organic and Conventional Farming Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 123–130.

- Matich, E.K.; Laryea, J.A.; Seely, K.A.; Stahr, S.; Su, L.J.; Hsu, P.-C. Association between Pesticide Exposure and Colorectal Cancer Risk and Incidence: A Systematic Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 219, 112327.

- Hatcher, J.M.; Delea, K.C.; Richardson, J.R.; Pennell, K.D.; Miller, G.W. Disruption of Dopamine Transport by DDT and Its Metabolites. Neurotoxicology 2008, 29, 682–690.

- Eskenazi, B.; Marks, A.R.; Bradman, A.; Harley, K.; Barr, D.B.; Johnson, C.; Morga, N.; Jewell, N.P. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 792–798.

- Andreotti, G.; Koutros, S.; Hofmann, J.N.; Sandler, D.P.; Lubin, J.H.; Lynch, C.F.; Lerro, C.C.; De Roos, A.J.; Parks, C.G.; Alavanja, M.C.; et al. Glyphosate Use and Cancer Incidence in the Agricultural Health Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 509–516.

- Soares, D.; Silva, L.; Duarte, S.; Pena, A.; Pereira, A. Glyphosate Use, Toxicity and Occurrence in Food. Foods 2021, 10, 2785.

- Worthington, V. Nutritional Quality of Organic versus Conventional Fruits, Vegetables, and Grains. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2001, 7, 161–173.

- Smith-Spangler, C.; Brandeau, M.L.; Hunter, G.E.; Bavinger, J.C.; Pearson, M.; Eschbach, P.J.; Sundaram, V.; Liu, H.; Schirmer, P.; Stave, C.; et al. Are Organic Foods Safer or Healthier Than Conventional Alternatives? A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 348.

- Lairon, D. Nutritional Quality and Safety of Organic Food. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 33–41.

- Crinnion, W.J. Organic Foods Contain Higher Levels of Certain Nutrients, Lower Levels of Pesticides, and May Provide Health Benefits for the Consumer. Altern. Med. Rev. J. Clin. Ther. 2010, 15, 4–12.

- Yu, X.; Guo, L.; Jiang, G.; Song, Y.; Muminov, M.A. Advances of Organic Products over Conventional Productions with Respect to Nutritional Quality and Food Security. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 53–60.

- Rembiałkowska, E. Quality of Plant Products from Organic Agriculture. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2757–2762.

- Brandt, K.; Leifert, C.; Sanderson, R.; Seal, C.J. Agroecosystem Management and Nutritional Quality of Plant Foods: The Case of Organic Fruits and Vegetables. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 177–197.

- Mozafar, A. Nitrogen Fertilizers and the Amount of Vitamins in Plants: A Review. J. Plant Nutr. 1993, 16, 2479–2506.

- Barański, M.; Rempelos, L.; Iversen, P.O.; Leifert, C. Effects of Organic Food Consumption on Human Health; the Jury Is Still Out! Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1287333.

- Barański, M.; Srednicka-Tober, D.; Volakakis, N.; Seal, C.; Sanderson, R.; Stewart, G.B.; Benbrook, C.; Biavati, B.; Markellou, E.; Giotis, C.; et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 794–811.

- Héroux, M.-È.; Adélaïde, L.; Allès, B.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Andreeva, V.A.; Assmann, K.E.; Balti, E.V.; Baudry, J.; Bénard, C.; Bertin, M. Key Findings of the French Bionutrinet Project on Organic Food-based Diets: Description, Determinants, and Relationships to Health and the Environment. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 208–224.

- Mie, A.; Andersen, H.R.; Gunnarsson, S.; Kahl, J.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Quaglio, G.; Grandjean, P. Human Health Implications of Organic Food and Organic Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 111.

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Mortality from All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g4490.

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Péneau, S.; Méjean, C.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D. Profiles of Organic Food Consumers in a Large Sample of French Adults: Results from the Nutrinet-Santé Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76998.

- Abete, I.; Romaguera, D.; Vieira, A.R.; de Munain, A.L.; Norat, T. Association between Total, Processed, Red and White Meat Consumption and All-Cause, CVD and IHD Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 762–775.

- Li, F.; Hou, L.; Chen, W.; Chen, P.; Lei, C.; Wei, Q.; Tan, W.; Zheng, S. Associations of Dietary Patterns with the Risk of All-Cause, CVD and Stroke Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 16–24.

- Baudry, J.; Pointereau, P.; Seconda, L.; Vidal, R.; Taupier-Letage, B.; Langevin, B.; Allès, B.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Amiot, M.-J.; et al. Improvement of Diet Sustainability with Increased Level of Organic Food in the Diet: Findings from the BioNutriNet Cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1173–1188.

- Guéguen, L.; Pascal, G. Organic Foods. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. B978012821848800158X. ISBN 978-0-08-100596-5.

- Vigar, V.; Myers, S.; Oliver, C.; Arellano, J.; Robinson, S.; Leifert, C. A Systematic Review of Organic Versus Conventional Food Consumption: Is There a Measurable Benefit on Human Health? Nutrients 2019, 12, 7.

- Eisinger-Watzl, M.; Wittig, F.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. Customers Purchasing Organic Food—Do They Live Healthier? Results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2015, 5, 59–71.

More