Drastic climate changes over the years have triggered environmental challenges for wild plants and crops due to fluctuating weather patterns worldwide. This has caused different types of stressors, responsible for a decrease in plant life and biological productivity, with consequent food shortages, especially in areas under threat of desertification. Nanotechnology-based approaches have great potential in mitigating environmental stressors, thus fostering a sustainable agriculture. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have demonstrated to be biostimulants as well as remedies to both environmental and biotic stresses. Their administration in the early sowing stages, i.e., seed priming, proved to be effective in improving germination rate, seedling and plant growth and in ameliorating the indicators of plants’ well-being. Seed nano-priming acts through several mechanisms such as enhanced nutrients uptake, improved antioxidant properties, ROS accumulation and lipid peroxidation. The target for seed priming by ZnO NPs is mostly crops of large consumption or staple food, in order to meet the increased needs of a growing population and the net drop of global crop frequency, due to climate changes and soil contaminations.

- seed priming

- ZnO NPS

- crops

- stress alleviation

1. Introduction

2. Seed Nano-Priming Mechanism NPs Entry

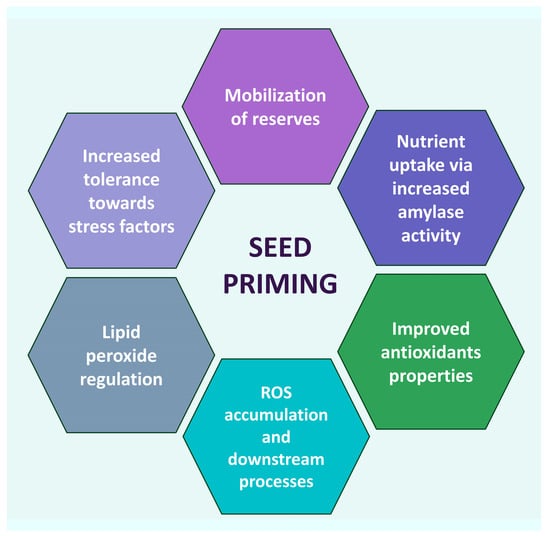

Seed priming by ZnO NPs may alleviate plants’ abiotic and biotic stress, act as a biostimulant causing an increase in germination rate, seedling and plant growth and overall fresh weight, and improve the biomass and photosynthetic machinery. The effects of seed priming are implemented through several mechanisms. NPs affect the germination and vigor of plants by the stimulation and improvement of seed metabolic rate, vigor index and seedling characteristics [48], especially in the case of ZnO NPs priming [49]. Furthermore, seed nano-priming plays a role in nutrient uptake. This is particularly important, since poor nutrient uptake negatively affects the whole growth process, including root formation, seedling growth, flowering, and fruit formation [50][51][50,51]. Implementing nutrient delivery by conventional management systems may not be efficient, thus opening the way to nano-priming technology [52][53][52,53]. In fact, NPs may improve nutrient uptake by altering the metabolism of seeds, for instance, by a steep rise in α-amylase activity via gibberellic acid [54], the breakdown of stored starch, and stimulation of the release of growth regulators, ultimately fostering the growth and productivity of plants. This can also be monitored by the activity of enzymes like α-amylase, which has a steep increase upon seeding. Management of the antioxidant system is crucial to a plant’s well-being, since it prevents potential cellular molecule damage by maintaining ROS homeostasis [55]. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant enzymes participate in the ROS management system: catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POX), ascorbate-peroxidase (APX), superoxide-dismutase (SOD), phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), glutathione, and glutathione reductase. Seed priming affects the antioxidant enzyme system of plants at several levels. It was observed that the activity of antioxidant enzymes increased at various degrees, depending on the type of plant and on the specific priming, though the exact action pathway was not quite fully disclosed. Some correlations were hypothesized, though. For instance, H2O2 radicals were significantly reduced in tomato, cucumber, and pea nano-primed seeds due to increased SOD and CAT activity [56][57][58][56,57,58]. On the other hand, H2O2 is responsible for carbonylating proteins, initiating and changing kinase transduction pathways; therefore, it can interfere with the expression of multiple genes in the germination process [59]. Seed nano-priming plays a role in ROS and lipid peroxide regulation. Seeds accumulated in the seed coat induce ROS accumulation and activate a number of downstream processes [60]. ROS are produced in plants’ chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes as a by-product during aerobic metabolism [61][62][61,62]. They may irreversibly damage DNA, but they also act as signaling molecules that allow plants to grow normally and mitigate abiotic stresses [63][64][63,64]. Increased ROS accumulation in plant cells upon seed nano-priming helps to break the bonds among the polysaccharides in the cell wall of seed endosperm, thus facilitating quick and healthy seed germination [65]. It triggers processes of breaking seed dormancy and stimulating seed germination [66] through the activation of the synthesis of gibberellic and abscisic acid [67][68][67,68]. The lowering of ROS by NPs may result in a large rise in antioxidant enzyme levels. This may help increasing tolerance towards stress factors, such as salinity and drought [69][70][69,70]. Heavy metals affect crop growth development and production, hampering plant growth progressions. However, in general, NPs regulate plant physiological and biochemical parameters to reduce their detrimental effects [71]. Several studies indicate a connection between NPs priming and decreases in toxic metal accumulations by stimulating antioxidant enzyme activities and decreasing ROS and lipid peroxidation [72]. A scheme of many nano-priming mechanisms is summarized in Figure 1.

3. Application to Different Crops

Nano-priming techniques are deemed beneficial for improving crop yields, frequencies and seedling and plant well-being. In this framework, great effort has been devoted to promote and support nanotechnologies in agriculture under different flagships such as the Nano Mission [78] of the Indian government to encourage private-sector investment and support the growth and commercial application of nanotechnology. Broad, systematic and low-cost applications of NPs on fields are general requirements for sustainable agricultural stimulation. The success of seed nano-priming as a form of biostimulation and an agent of contrast against abiotic and stresses varies based on the species of plants and the characteristics of treating agents. However, ZnO NPs appear to be very efficient and versatile among nanoparticles, for seed nano-priming purposes, since they are suitable for targeting different types of crops worldwide. Besides this, their production is low cost and can be achieved with environmentally friendly methods [79]. Crops which were successfully tested for ZnO NPs nano-priming include produce grown in localized areas, as well as global harvests. Large consumption cereals are a primary target for improved production, in dry, salty and contaminated soils, especially since cereal crops play an important role in satisfying daily calorie intake in the developing world. However, the Zn concentration in grain is inherently very low, particularly when grown on Zn-deficient soils. Rice alone (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the major staples, feeding more than half of the world’s population. It is grown in more than 100 countries, predominantly in Asia [80]. Hence, rice, wheat, maize, sorghum, chickpeas and several varieties of faba beans (lupine, vigna mungo, vigna radiata and vicia faba) were recently probed for seed priming with ZnO NPs. However, tests are also being performed on different types of edibles, such as spinach (basella alba) and tomatoes. Finally, textile fibers (cotton) and vegetables for animal feed and industrial oil production (rapeseed, Brassica napus L.) were also investigated for ZnO NPs seed priming.4. ZnO NPs Seed Priming against Abiotic Stresses

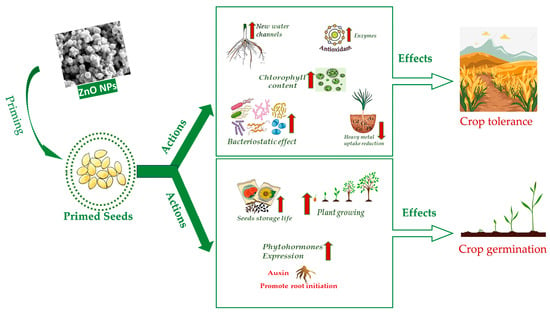

The efficacy of seed priming is dose dependent, and investigations may be carried out in vitro, in pot or in field. In the following sections, a summary of the latest research is reported on the effects of ZnO NPs priming on the most widespread crops worldwide. Drought, soil salinity and heavy metal and arsenic accumulation are listed among abiotic stresses as well as improper seed storage. In addition, action against biotic stresses is considered in association with biotic remedies. The sheer biostimulating effect of ZnO NPs is also reported. Details are mentioned for the major effects, doses and mechanisms when specified in the original papers. The ZnO NPs used in the experiments were of two types, commercial or purposely synthetized. Information on ZnO NPs preparation and characterization methods was reported where available. Figure 2 summarizes the main actions of ZnO NPs seed priming and the consequent effects on crops. The type of stress, ZnO NPs doses, target plants and major benefits of seed priming are reported in Table 1, whereas the type of ZnO NPs and the synthesis and characterization methods (if available) are reported in Table 2.

|

Application |

Type of Seed |

|---|

|

ZnO NPs Source | Doses |

Reagents and Conditions Effects |

Ref. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Characterization |

Size and Purity |

Refs. |

|||||||

|

Drought stress alleviation |

Rice |

0; 5; 10; 15; 25; 50 ppm |

Agronomic profile yield |

||||||

|

Purchased |

Not Reported |

20–30 nm 98% purity level |

[81] |

||||||

[ | ] |

Wheat |

40; 80; 120; 160 ppm |

||||||

|

Purchased | Chlorophyll content and plant nutrients |

[82 |

] |

||||||

UV–Vis, TEM, XRD * |

Not reported—99,99%purity level |

[82] |

Wheat |

10 mg/L |

Reduced DNA damage |

[83] |

|||

|

Purchased |

Not Reported |

Not Reported |

Salt stress alleviation |

Sorghum bicolor |

Zn(NO3)2 ·6H2O, Agathosma betulina, 80 °C, calcination 600 °C |

5; 10 mg/L |

UV–Vis, TEM, XRD, FTIR, SEM | ||

50 mg/L |

Improved germination |

[86] |

|||||||

|

Rapeseed |

|||||||||

] | |||||||||

[ | ] |

20–30 nm |

[84] |

25; 50; 100 mg/L |

Increased vigor indexes |

[87] |

|||

|

Purchased |

36 nm |

[90] |

|||||||

|

Phyto-Synthesis |

Zn(ac)2 ·2H2O V. mungo extract, 70 °C |

UV–Vis, SEM, XRD |

30–80 nm |

[91] |

|||||

|

Biogenic synthesis |

Zn(ac)2 ·2H2O, T. Harzanium, 40 °C, calcination 500 °C |

UV–Vis, FTIR, TEM, SEM, EDX, XRD |

5–27 nm, agglomerated |

[92 | |||||

Wheat | |||||||||

10 mgL−1 |

Increased germination, vigor index and chlorophyll content |

[100] |

|||||||

|

Phyto-Synthesis | Increased Fresh weights |

[84] |

|||||||

|

Wheat |

50 mg/L |

Increased plant growth, grain yield and macronutrients |

Not reported [85] |

||||||

<50 nm | [85] |

Wheat |

|||||||

|

Purchased |

Not reported |

<100 nm |

[86] |

||||||

|

Precipitation |

ZnSO4·7H2O, NaOH, drying 100 °C |

XRD, IR, SEM, TEM |

~20 nm |

[87] |

Cu stress alleviation |

||||

|

Purchased |

Wheat |

20 ppm |

Improved growth |

XRD, EDX, TEM, SEM [ |

~20 nm-99% purity 86] |

||||

[ | ] |

Co stress alleviation |

|||||||

|

“Chemical” |

Maize |

ZnSO4, citrate, 70 °C 500 mg/L |

DLS, TEM Improved plant growth, biomass and photosynthetic machinery |

spherical shape ~ 193 nm High purity [88] |

|||||

[ | ] ** |

Pb stress alleviation |

Basella alba |

200 mg/L |

Increased seed germination, seedling and roots growth, seed vigor; reduced Pb uptake |

[89] |

|||

|

Purchased |

SEM, TEM * |

Cd stress alleviation |

Rice |

0; 25; 50; 100 mg/L |

Improved early growth and related physio-biochemical attributes |

[90] |

|||

|

Arsenic stress alleviation |

V. mungo (bean) |

50; 100; 150; 200 mg/L |

Increased germination by modulation of metabolic pathways |

[91] |

|||||

] |

Biotic stress counteraction |

Chickpea |

|||||||

|

Purchased | 0.25; 0.50; 0.75; 1.0 µg/mL 1000 mg/kg |

XRD Antifungal Activity |

15–25 nm [92] |

||||||

[ | ] |

Reduction in disease indices |

|||||||

|

Precipitation |

[93] |

||||||||

|

Zn(NO3)2 ·6H2O, NaOH, 55 °C, vacuum 60 °C |

SEM, EDAX, TEM, Raman |

Narrow rods— 80–150 nm |

[94] |

Seed storage |

|||||

|

Wet chemical synthesis | V. radiata (bean) |

Trichoderm asperellum |

1000 ppm |

UV–Vis, SEM, TEM, FTIRIncreased germination percentage |

[ |

spherical shape, 33.4 nm 94] |

|||

[ | ] | ** |

Chickpea |

100 ppm |

increased seed storage life; decreased disease incidence |

||||

|

Precipitation |

Zn(ac)2 ·2H2O, KOH, 60 °C, dried at 60 °C |

UV-Vis, XRD, SEM, FTIR |

[95] |

||||||

Hexagonal shape | 20 nm |

[96] |

Crop improvement |

Wheat |

5; 10; 15; 20 ppm |

Increased plant growth |

|||

|

Biogenic synthesis |

Zn(NO3)2, ZnSO4, ZnCl2 fungi, from arid field | [ | 96] |

||||||

DLS, TEM-EDX, zeta potential |

10 nm |

[97] ** |

Oryza sativa (rice) |

10 µmol |

|||||

|

Phyto-Synthesis | Seedling vigor; increased plant chlorophyll content; nutrients uptake |

Zn(ac)2 ·2H2O, Coriandrum sativum, 70 °C, calcination 500 °C |

[97] |

||||||

UV–Vis, FTIR, TEM, SEM, XRD |

spherical shape 30 nm |

[98] |

Tomato |

||||||

|

Precipitation | 100 ppm |

Zn(NO3)2 ·6H2O, NaOH, 55 °C, Dried at 60 °C |

Improved germination process |

[98] |

|||||

UV –Vis, FTIR, TEM, SEM |

spherical shape 36 nm |

[99] |

Cotton |

400 ppm |

Increased germination and seed parameters |

||||

|

Purchased |

UV –Vis, XRD, TEM |

[99 |

spherical shape 20–30 nm |

[100] |

|||||

|

Precipitation |

Zn(NO3)2 ·6H2O, NaOH 40 °C–60 °C |

XRD, FTIR, SEM, TGA |

58–60 nm |

[101] |

V. faba (bean) |

50, 100 mgL−1 |

Increased biometric parameters, chlorophyll content |

[101] |

* data provided by the manufacturer; ** and references therein.