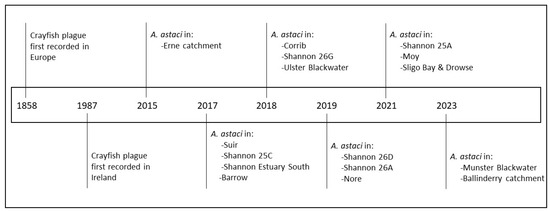

Crayfish plague is a devastating disease of European freshwater crayfish and is caused by the oomycete Aphanomyces astaci (A. astaci), believed to have been introduced to Europe around 1860. All European species of freshwater crayfish are susceptible to the disease, including the white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes. A. astaci is primarily spread by North American crayfish species and can also disperse rapidly through contaminated wet gear moved between water bodies. This spread, coupled with competition from non-indigenous crayfish, has drastically reduced and fragmented native crayfish populations across Europe. Remarkably, the island of Ireland remained free from the crayfish plague pathogen for over 100 years, providing a refuge for A. pallipes. However, this changed in 1987 when a mass mortality event was linked to the pathogen, marking its introduction to the region.

- crayfish plague

- Aphanomyces astaci

- Austropotamobius pallipes

- invasive species

- Ireland

1. Introduction

2. Aphanomyces astaci in Ireland

2.1. Historical Incidence of Crayfish Plague in Ireland

2.2. Recent Cases of Crayfish Plague in Ireland

2.3. Reservoir Species and Alternative Host of Aphanomyces astaci

Aphanomyces astaci is primarily known as a pathogen of freshwater crayfish but has been observed to infect other freshwater decapods. Some freshwater-inhabiting crabs such as the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) are known carriers of A. astaci, likely obtained from coexisting crayfish populations, and can transmit the pathogen to susceptible crayfish species [19][20][21][22][23,24,25,26]. Although E. sinensis was reported in Ireland in 2006, its limited sightings and proximity in Waterford harbour suggest a minimal role in A. astaci’s current distribution in Ireland [23][27]. Therefore, Chinese mitten crabs are unlikely to be involved in the current distribution of A. astaci in Ireland. Ornamental freshwater shrimps like Macrobrachium dayanum and Neocaridina davidi, established in thermally polluted German streams [24][28], show resistance to A. astaci and may facilitate its transmission [20][24]. However, those freshwater shrimp species have not been recorded in the wild in Ireland. The presence of invasive freshwater decapods such as E. sinensis in the south of Ireland, and their potential to transmit A. astaci, underscores the need for research to determine if common freshwater organisms in Ireland can also act as vectors for the pathogen.2.4. The Genetic Lineages of Aphanomyces astaci in Ireland

The attempts to determine the genetic lineages of A. astaci in Ireland are provided here with the caveat that those data have not been assessed by peer review and the raw data to assess the validity of those assays have not yet been provided by the NCPSP. Determining the genetic lineages of the pathogen at sites of infection can provide insights into the introduction and spread of A. astaci and could inform future conservation measures. Five genotypes of A. astaci were previously defined (A-E) from pure isolates using the random amplification of polymorphic DNA-PCR [25][30]. A PCR assay was later designed to determine the same genotypes following the whole genome sequencing of the isolates [26][31]. A more sensitive qPCR assay was later designed to identify the same genotypes [27][32] and was utilised by the NCPSP in the 2020–2021 NCPSP report. The majority of genetic sampling was completed using tissue samples. Genotyping from eDNA using qPCR alone is not yet a standard method due to variable DNA concentrations at sites and is not routinely used. However, genotyping would be possible where the A. astaci DNA concentration is sufficient in the environment. Given the varying results presented in the two NCPSP reports, the lack of peer review and accountability for those data, and the lack of data from NI, genotyping of all samples should be outsourced to expert labs. This would validate the NCPSP’s results but also help ascertain the genetic lineages in Northern Ireland.3. The Distribution of Aphanomyces astaci across Ireland

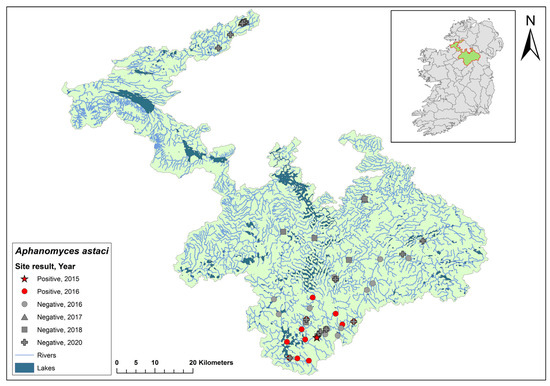

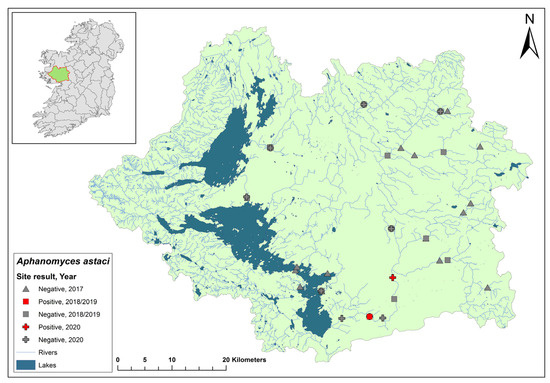

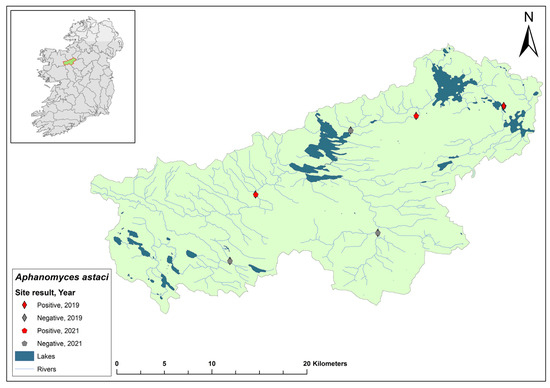

3.1. The Erne Catchment

The Erne catchment (ID 36) spans an area of 4415 km2 across Ireland (2512 km2) and Northern Ireland (1903 km2), and fresh water from the catchment enters the sea in Co. Donegal (Figure 3). The catchment contains 129 rivers, 130 lakes, and 66 groundwater bodies. Following the initial crayfish plague outbreak in July 2015, the NPWS commissioned a study of the Erne catchment to evaluate local crayfish populations and to gauge the persistence of A. astaci in the area. One year later, the investigation was undertaken by a research team from Atlantic Technological University in August 2016. The team employed hand searching, netting, or overnight trapping to determine the presence of A. pallipes and NICS, if possible, throughout the Erne catchment (Figure 3).

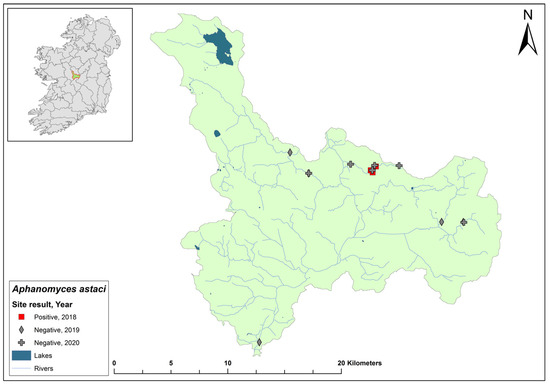

3.2. Barrow Catchment

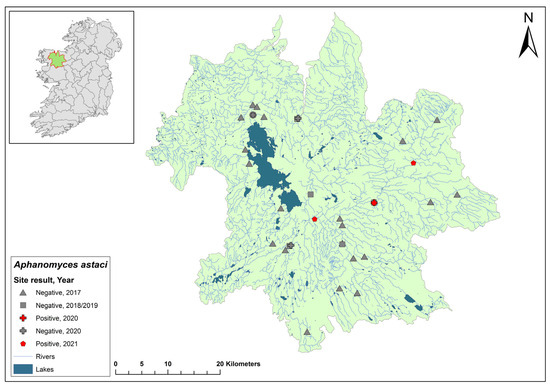

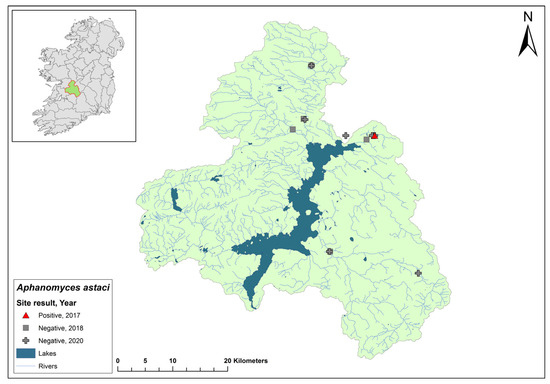

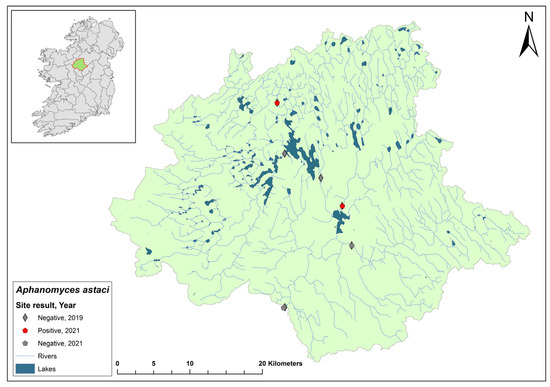

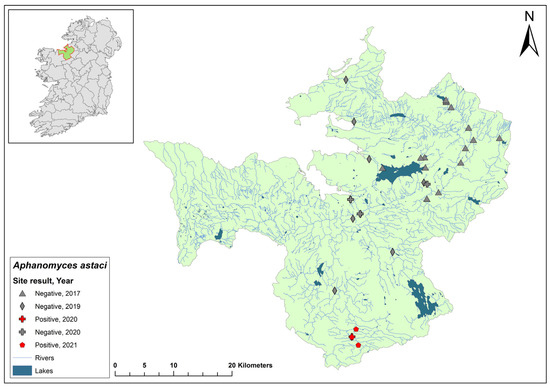

3.3. Corrib Catchment

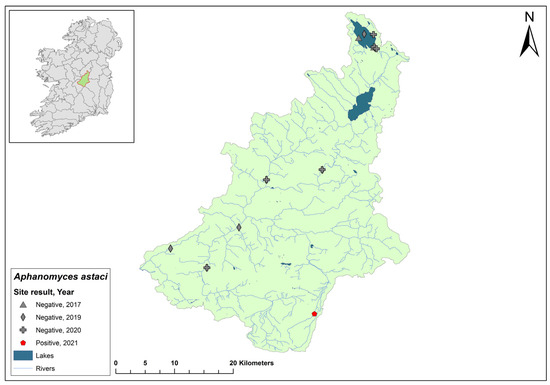

3.4. Moy & Killala Bay Catchment

3.5. Nore Catchment

3.6. Shannon Estuary South Catchment

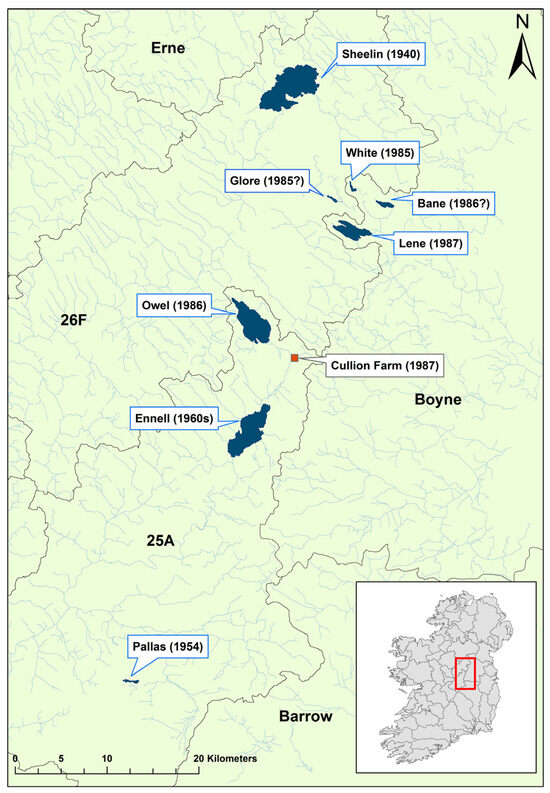

3.7. Lower Shannon (Brosna) 25A Catchment

3.8. Lower Shannon (Lough Derg) 25C Catchment

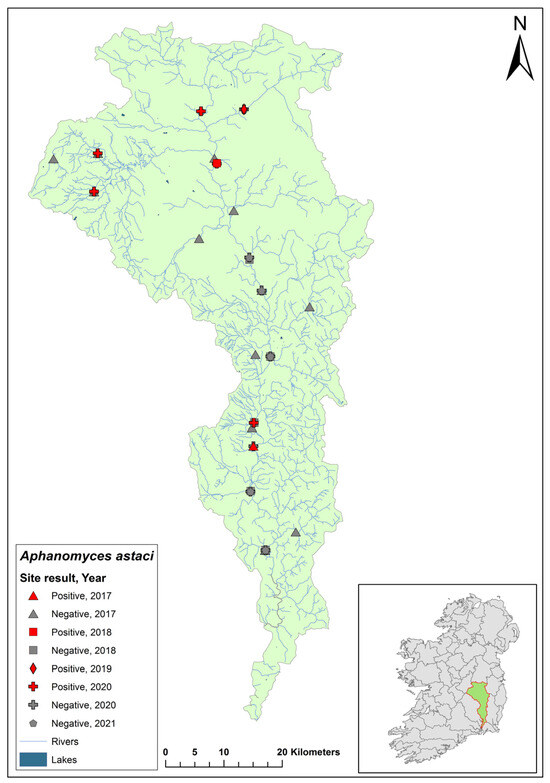

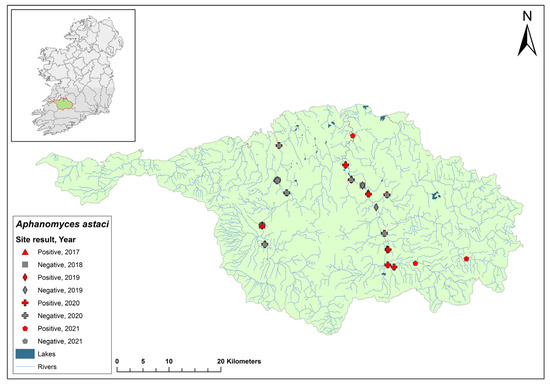

3.9. Ulster Blackwater Catchment

3.10. Upper Shannon (Lough Allen) 26A Catchment

3.11. Upper Shannon (Boyle) 26B Catchment

3.12. Upper Shannon 26C

3.13. Upper Shannon (Suck) 26D Catchment

3.14. Shannon 26G Catchment

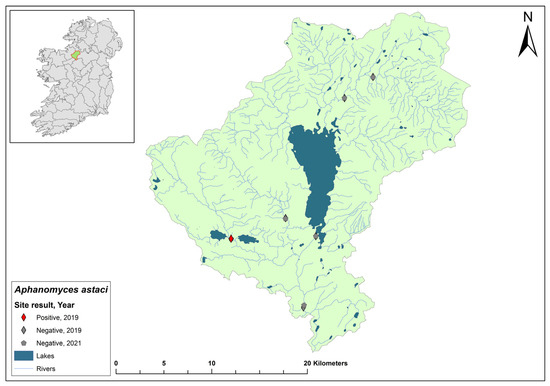

3.15. Sligo Bay & Drowse Catchment

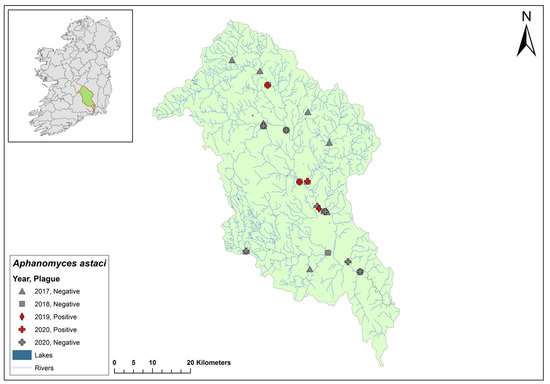

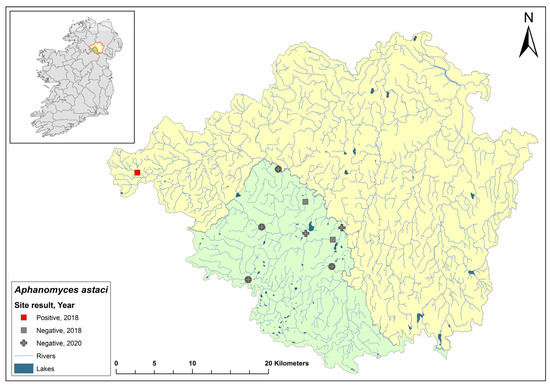

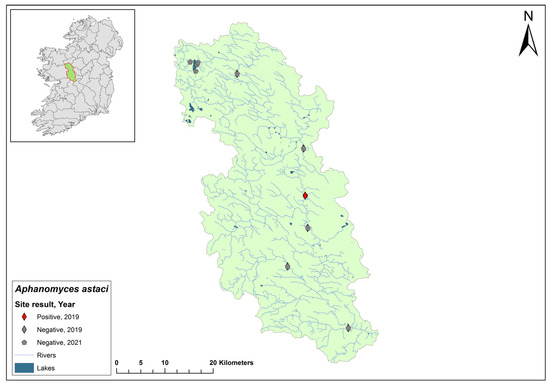

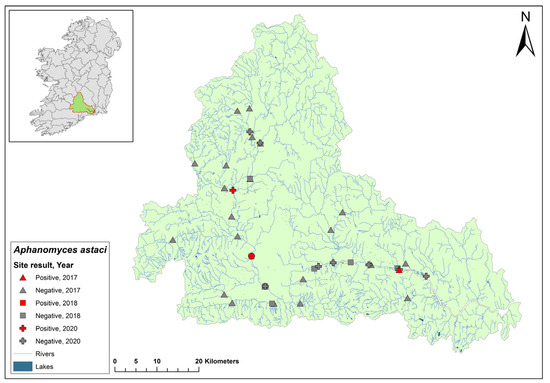

3.16. Suir Catchment

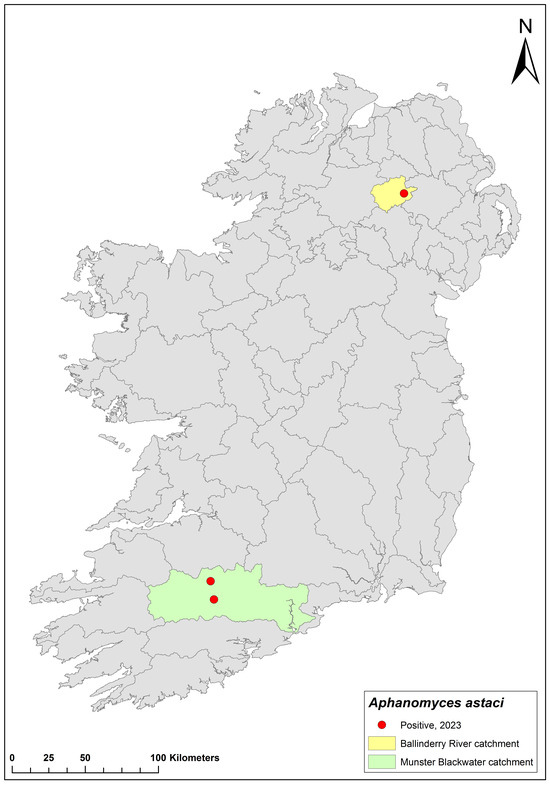

3.17. Outbreaks between 2021 and 2023

4. Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species

4.1. Legislative Changes Regarding Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species

4.2. Wild, Established Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species in Ireland

The first record of established wild NICS in Ireland was reported in 2019 with the presence of a strong population of Common Yabby (Cherax destructor) in Ballyhass Lake, a former quarry in Co. Cork [29][40]. The species typically requires higher temperatures to survive than are present in Ireland year-round, and Ballyhass Lake is fed by a thermal spring [29][40]. The stock is estimated to have been present at the site for ten years, while no records of C. destructor have been reported elsewhere in the local area. In experimental trials, C. destructor was shown to be generally susceptible to A. astaci infection [30][41], but some survival was observed after infection with the least virulent A. astaci strain [31][42]. Therefore, under favourable conditions, C. destructor could transmit A. astaci in Ireland [31][42]. It has not been reported whether the Ballyhass lake population of C. destructor have been tested for A. astaci.4.3. No Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species Found during the 2016–2021 Surveys

The 2016 Erne catchment survey assessed the presence of NICS via conventional hand searching, netting, or overnight trapping methods and no NICS were found. Likewise, during the 2017 national crayfish survey, no NICS were found using hand searching, netting, or overnight traps. Subsequently, the NCPSP developed a multiplex qPCR assay (one reaction detecting two or three species of NICS each) to test for eight species of NICS, including the following species: signal crayfish (P. leniusculus), noble crayfish (A. astacus), spiny-cheek crayfish (F. limosus), marbled crayfish (P. virginalis), red-swamp crayfish (P. clarkii), common yabby (C. destructor), narrow-clawed crayfish (A. leptodactylus), and virile crayfish (F. virilis). However, parameters and validation data of this multiplex assay developed by the Marine Institute have not been published [32][21]. During the NCPSP monitoring programs, no evidence for NICS was found.4.4. The Sale of Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species in Ireland through the Pet Trade

Ornamental crayfish from the pet trade have been confirmed as carriers of A. astaci previously and represent a threat physically and by their contaminated water being released into the environment [33][34][43,44]. In Ireland, NICS have been available for purchase online through the pet trade. P. virginalis, P. clarkii, C. quadricarinatus, and Cambarellus patzcuarensis have been reported for sale in 2015 and 2017 [35][36][45,46].5. Management and Mitigation Strategies

Authorities in both Ireland and Northern Ireland appear to have taken a laissez-faire non-intervention approach to the management of NICS and A. astaci. Research funding related to A. astaci in Ireland has primarily focused on monitoring and determining the spread of the plague pathogen across water catchments; a surveillance programme was established without a mitigation or management programme. Yet, surprisingly, proactive restrictions have not been imposed, such as limiting the movement of wet gear and watercrafts between waterbodies during active mass mortality events. While efforts were taken to publicise the initial plague event and subsequent outbreaks, including a detailed press release by Inland Fisheries Ireland [17], the emphasis has largely been on passive voluntary preventative measures. “Voluntary bans’’ were placed, extended, and lifted on several waterbodies.

The data indicate that the voluntary bans were ineffective at curbing the spread of A. astaci, and this measure was criticised by stakeholders, including the angling community, for not adequately protecting A. pallipes [37][38][48,49]. Stakeholders received advice on the “Check, Clean, Dry” protocol when transitioning between watercourses, and similar literature and videos were disseminated online [39][40][50,51]. Signs informing the public about crayfish plague and detailing the protocol were prominently placed at high-traffic watercourses. Yet, the continued spread of A. astaci to new catchments suggests these passive measures have been ineffective.

The legislative change made in 2018 to prohibit the trade of five NICS in the country is arguably the strongest effort made to protect the freshwater environment but is also lacking. Only five species of NICS were prohibited. Considering Ireland only has a single protected species of freshwater crayfish, the legislation could have been extended to all freshwater crayfish species, as interfering with A. pallipes was already prohibited. Neither the established population of C. destructor nor C. patzcuarensis, recently being sold online, are listed in the 2018 legislation. Regarding Northern Ireland, similar efforts to those by southern authorities were made online to advertise crayfish plague, with the same “Check, Clean, Dry” protocols [40][51]. However, there is little evidence of any effort to monitor the distribution of A. astaci in Northern Ireland and no scientific or grey literature can be found as of 1st of January 2024.