Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Olli Pekka Suomalainen and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrythmia and one of the strongest risk factors and causal mechanisms of ischemic stroke (IS). Acute IS due to AF tends to be more severe than with other etiology of IS and patients with treated AF have reported to experience worse outcomes after endovascular treatment compared with patients without AF. As cardioembolism accounts for more than a fifth of ISs and the risk of future stroke can be mitigated with effective anticoagulation, which has been shown to be effective and safe in patients with paroxysmal or sustained AF, the screening of patients with cryptogenic IS (CIS) for AF is paramount.

- atrial fibrillation

- hemorrhagic stroke

- ischemic stroke

1. Introduction

Stroke remains among the leading causes of mortality and long-term disability globally [1][2][1,2]. Atrial fibrillation (AF), in turn, is the most common sustained arrhythmia and one of the strongest risk factors and causal mechanisms for ischemic stroke (IS) [3][4][5][6][7][3,4,5,6,7]. Cardioembolic causes account for 20–25% of all IS patients, with known AF being by far the most frequently documented source for cardioembolism [4][8][9][10][11][4,8,9,10,11]. The incidence of AF increases strongly with age, leading to a prevalence of almost 20% in a population aged more than 85 years [9][12][9,12]. As AF can account for at least a fifth of cases with IS and the strokes caused by AF tend to be more severe than other types of IS, AF is a major modifiable risk factor for IS, including disabling stroke [4][8][9][4,8,9]. Anticoagulation in patients with IS and AF has shown to be effective and safe [4][13][4,13]. The flipside of the coin is that anticoagulation can also lead to both hemorrhagic stroke and hemorrhagic transformation (HT) of IS in patients with AF [4].

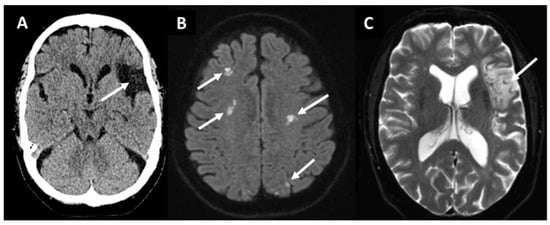

In one third of IS patients, the etiology of stroke remains cryptogenic despite standard diagnostic evaluations and, in such circumstances, screening for occult paroxysmal AF is recommended [4][10][14][4,10,14]. Brain imaging findings of IS patients raising a suspicion of cardioembolism include an acute or chronic ischemic cortical, but not lacunar lesions, multi-territorial (cortical) lesions with a high prevalence in posterior circulation and with possible HT [11][15][16][11,15,16]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to reveal the embolic pattern of IS which is not shown in non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) scans (Figure 1B) [16].

Figure 1. Non-contrast computed tomography (A) showing a chronic embolic stroke of undetermined source (arrow) in a 66-year-old woman in the left middle cerebral artery territory. Magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging (B) revealing ischemic lesions (bright spots indicated by arrows) in multiple territories in a 78-year-old man with chronic atrial fibrillation. T2*-weighted imaging (C) showing a subacute lesion (arrow) in the left middle cerebral artery territory in a patient with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

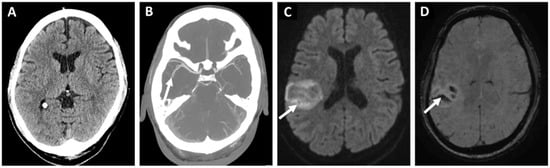

The embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) concept defines a subclass of cryptogenic IS (CIS) with a higher likelihood of detecting occult AF through prolonged monitoring (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [11][17][11,17]. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Stroke Organization (ESO) guidelines recommend that patients with CIS or transient ischemic attack (TIA) should undergo at least 72 h of ECG monitoring, with further prolonged screening after initially negative screening being recommended [13][18][13,18]. It is well documented that longer screening leads to an increased rate of positive AF paroxysms [4][13][18][19][20][4,13,18,19,20].

Figure 2. 76-year-old woman with hypertension and dyslipidemia presented with a sudden onset left hemiparesis and dysarthria. Initial non-contrast computed tomography (A) showed no acute hypodensity. The patient received immediate intravenous thrombolysis after which computed tomography angiography (B) revealed a right-sided middle-cerebral artery occlusion in the M2 segment too distal to be treated with endovascular treatment. Despite thrombolysis, the next day magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging (C) showed a cortical infarction (arrow) with a moderate hemorrhagic transformation in the susceptibility weighted imaging (D). Etiologic classification for the stroke was embolic stroke of undetermined source (arrow) after initial diagnostic work-up. And implantable loop monitor inserted 11 weeks later revealed a paroxysmal atrial fibrillation as the probable source of the embolism.

Oral anticoagulation (OAC), either with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) in valvular AF or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in non-valvular AF effectively mitigates the risk of recurrent IS in patients with AF. Recent data suggest that early initiation of DOAC after TIA or IS due to AF is safe compared to later initiation. However, OAC may predispose some patients for intracranial bleeding, including intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), subarachnoid hemorrhage, and traumatic intracranial hemorrhage [3][5][3,5]. The association of silent cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) with occult AF and the role of anticoagulation in AF patients with CMBs is still unclear [8]. Left atrial appendix closure (LAAC) offers an option for anticoagulation treatment as the primary or secondary prevention of thromboembolism in AF patients with anticoagulation-related spontaneous intracranial bleeding or other contraindication for anticoagulation or in breakthrough IS, i.e., despite proper anticoagulation treatment. However, it is still unclear whether these patients should be left untreated or treated with aspirin, VKA/DOAC, or with LAAC [8].

2. Primary and Secondary Prevention of IS in Patients with AF

Earlier studies have shown that, compared to non-AF IS, IS associated with AF is likely to be more severe and cause greater disability, fatality, and costs [7][21][22][7,104,105]. These patients are usually older and AF-associated IS most commonly causes larger tissue damage and tends to present in the middle cerebral artery territory. However, research thus far has mostly assessed short-term recovery and mortality after AF-associated stroke, and contemporary data on the long-term outcomes is scarce. Older follow-up studies from almost 30 years ago have reported up to a two-fold mortality in stroke patients with AF compared to patients with no AF. For example, in the Copenhagen Stroke Study, the odds ratio for 30-day mortality was 1.7 (95% CI 1.2–2.5), and in the Framingham Study 1.8 (95% CI 1.1–3.3) [23][24][36,37]. Furthermore, some studies reported an increased risk of death being highest within the first weeks after AF-associated IS [25][106]. The risk of annual recurrence has been suggested to be up 10%, even in anticoagulated AF patients, and the mortality up to 50% within 2 years after the index stroke [26][27][107,108]. The risk of IS in AF patients can be reduced with appropriate selection of OAC, either with warfarin or DOACs (i.e., rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, or dabigatran). Based on indirect estimates, anticoagulation reduces the risk by approximately two thirds (60–70%) compared to placebo, regardless of the baseline risk [28][109]. Notably, OAC use also reduces the severity of IS, results in lower rates of large vessel occlusion and in a better 3-month functional outcome after IS, compared to patients with AF and no OAC at the time of the stroke [29][110]. Current guidelines recommend DOACs over vitamin K antagonists as the first-line stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular AF [13][30][13,111]. In a meta-analysis of four pivotal randomized controlled landmark trials (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY), Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF), Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE), and Edoxaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (ENGAGE AF)) investigating DOACs, DOACs were associated with a significant 19% reduction in stroke/systemic embolism, a favorable risk–benefit profile, and a similar IS risk reduction compared with warfarin, although with increased gastrointestinal bleeding [31][112]. The relative efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants was consistent across a wide range of patients. Moreover, DOACs possessed a 52% reduction in intracranial hemorrhage compared with warfarin, and a 10% reduction in all-cause mortality [32][44]. However, DOACs are not recommended in patients with mechanical heart valves—for instance, the randomized phase II study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of oral dabigatran etexilate in patients after heart valve replacement (RE-ALIGN) trial compared dabigatran versus warfarin in valvular AF but was prematurely stopped due to a high rate of adverse events, both thromboembolic and bleeding, in the dabigatran arm [33][113]. Finally, a newer class of OACs, factor XIa inhibitors, is under investigation. These include asundexian, which in the safety of the oral factor Xia inhibitor asundexian compared with apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation (PACIFIC-AF) phase 2 trial, was shown to be well tolerated and had a lower risk of bleeding compared with apixaban [34][114]. Phase 3 trials of factor XIa are currently running. There are no randomized trials assessing the safety and efficacy of different anticoagulation regiments specifically in the setting of secondary prevention in AF patients who have experienced a prior IS or TIA. Nevertheless, a pooled analysis of randomized trials in the ESO guidelines on AT treatment for secondary prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic events in patients with IS or TIA and non-valvular AF concluded that DOACs are superior in safety and at least as efficacious as warfarin in secondary prevention [35][115]. Many patients with AF also have concomitant coronary artery disease and AT therapy is often administered in conjunction with OAC therapy or as substitution. The Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field-Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF) trial, studying AF patients with or without acute coronary disease, showed that previous acute coronary syndromes were associated with worse 2-year outcomes, major bleeding, and a greater likelihood of undertreatment with OAC, while two thirds of patients received AP therapy [36][116].2.1. Timing of OAC Initiation after IS and Its Impact on Short-Term Outcomes

Data on the optimal timing for OAC initiation after IS is still relatively limited. Traditionally, initiation of OAC has usually been delayed, reducing the risk of HT. However, the risk of HT must be balanced with the increasing risk of recurrent thromboembolism, especially within the first days to weeks after the index stroke. In 2013, the European Heart Rhythm Association suggested a 1–6–12-day rule, i.e., the number of days from the occurrence of IS to OAC initiation based on the stroke severity measured with the NIH stroke scale [37][117]. Similar recommendations have been published by ESO and the American Heart/Stroke Association (AHA/ASA). Until recently there has been no high-quality RCT on this topic and each recommendation was based on expert opinions. However, two very recent trials, the Early Versus Delayed Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant Therapy After Acute Ischemic Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation (TIMING) trial and the Early Versus Late Initiation of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Post-Ischaemic Stroke Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (ELAN) trial, reported that early initiation of DOAC was non-inferior to a delayed start with no safety concerns [38][39][118,119]. In the ELAN trial, the 30-day recurrent IS rate was 1.4% in the early treatment vs. 2.5% in the late treatment group (OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.29–1.07). In the ELAN trial, the early initiation of OAC after IS ranged from 48 h to 6–7 days, depending on stroke severity (minor, moderate, and large IS). Neither the ELAN nor the TIMING trial included patients with such parenchymal hemorrhage or other cause that the treating clinician did not permit randomization. These results implied that early initiation of DOAC should be considered in patients eligible for DOAC treatment. Notably, bridging with low-molecular weight heparins cannot be recommended before starting OAC [40][120].2.2. LAA

A recent prospective multicenter observational study showed that patients with AF suffering from IS despite being on DOAC (“breakthrough IS”) have a high risk of recurrent stroke and bleeding during a mean follow-up time of almost 16 years [41][121]. The rates did not differ in patients who changed or did not change from one DOAC to another. Patients with IS while using OACs are shown to have an increased risk of all-cause death and further stroke recurrences (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) [29][110]. Breakthrough strokes are not uncommon in clinical practice, and they are associated with poor prognosis, while the mechanism of underlying OAC failure is still not completely understood, making the prevention of recurrent events a challenge without proper guidelines [42][122]. In these patients, there is no evidence to support switching from one DOAC to another or between a good-quality vitamin K antagonist and DOAC (or vice versa), regarding the risk of recurrent IS [43][44][123,124]. In such cases, LAAC, also with lower bleeding risks, might be considered as an alternative treatment strategy, but the overall benefit still remains unclear. An ongoing Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Versus Novel Oral Anticoagulation for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (Occlusion-AF) compares DOACs with LAAC in patients with a recent (less than 6 months) ischemic stroke. In addition, other studies on the breakthrough IS population are on the way (Table 1) [42][122].Table 1. Ongoing and planned trials on secondary prevention after ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, and intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation.

| Early vs. Late Initiation of Anticoagulation after Ischemic Stroke | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Time Frame | Study Sites | Sample Size |

| OPTIMAS (NCT03759938) |

Early (within 4 days) vs. standard (7 to 14 days) initiation of DOAC | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or systemic embolism. | 3 months | United Kingdom | 3478 |

| Left atrial appendage closure after ischemic stroke | |||||

| Occlusion-AF (NCT03642509) |

LAAC vs. DOAC within 180 after ischemic stroke | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality. | 5 years | Scandinavia | 750 |

| ELAPSE | LAAC and DOAC vs. DOAC alone | Ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death. | 4 years | Not yet provided | 482 |

| LAAOS-4 (NCT05963698) |

LAAC and OAC vs. OAC alone | Ischemic stroke or systemic embolism. | 4 years | Not yet provided | 4000 |

| Other secondary prevention after ischemic stroke | |||||

| INTERCEPT (NCT05723926) |

Bilateral carotid filter implants and OAC vs. OAC alone | Ischemic stroke. | UNK | Not yet provided | 200 |

| STABLED (NCT03777631) |

Catheter ablation and OAC vs. OAC alone 1 to 6 months after ischemic stroke | Ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, all-cause death, and hospitalization for heart failure. | 3 years | Japan | 250 |

| OCEANIC-AF (NCT05643573) |

FXIa inhibitor (asundexian) vs. apixaban mainly as primary prevention but also includes patients with prior ischemic stroke or TIA | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or systemic embolism. | 3 years | America, Europe, Asia, Australia | 18,000 |

| LIBREXIA-AF (NCT05757869) |

FXIa inhibitor (milvexian) vs. apixaban mainly as primary prevention but also includes patients with prior ischemic stroke or TIA | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or systemic embolism. | 4 years | America, Europe, Asia, Australasia, Africa | 15,500 |

| Oral anticoagulation resumption intracerebral hemorrhage | |||||

| ASPIRE (NCT03907046) |

Apixaban vs. aspirin 15 to 180 days after ICH | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or all-cause mortality. Time frame 3 years. |

3 years | United States | 700 |

| ENRICH-AF (NCT03950076) |

Edoxaban vs. either no antithrombotic therapy or antiplatelet monotherapy | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or major hemorrhage. | 2 years | America, Europe, Asia, Africa | 1200 |

| PRESTIGE-AF (NCT03996772) |

DOAC vs. no anticoagulation 15 to 180 days after ICH | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic). | 3 years | Europe | 350 |

| STATICH (NCT03186729) |

Anticoagulant treatment vs. no anticoagulant treatment 1 to 180 days after ICH | Fatal or non-fatal symptomatic recurrent ICH. | 2 years | Scandinavia | 500 |

| Left atrial appendage closure after intracerebral hemorrhage | |||||

| A3ICH (NCT03243175) |

Apixaban vs. LAAC vs. no intervention at least 14 days from ICH | Fatal or non-fatal major cardiovascular/cerebrovascular ischemic or hemorrhagic events. | 2 years | France | 300 |

| STROKECLOSE (NCT02830152) |

LAAO vs. medical therapy after 4 to 52 weeks after ICH | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), systemic embolism, life-threatening or major bleeding, or all-cause mortality. | 5 years | Europe | 750 |