During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in the incidence of overweight and obesity in children was observed. It appears that unhealthy food choices, an unbalanced diet, and a sedentary lifestyle, as well as experiencing stress related to the pandemic, may be contributing to this disturbing trend. Chronic stress is a significant factor contributing to eating disorders and obesity in youngsters, involving medical, molecular, and psychological elements. Individuals under chronic stress often focus on appearance and weight, leading to negative body image and disrupted relationships with food, resulting in unhealthy eating behaviors. Chronic stress also impacts hormonal balance, reducing the satiety hormone leptin and elevating the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin, fostering increased hunger and uncontrolled snacking. Two systems, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the sympathetic system with the adrenal medulla, are activated in response to stress, causing impaired secretion of noradrenaline and cortisol. Stress-related obesity mechanisms encompass oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, insulin resistance, and neurohormonal and neurotransmission disorders. Stress induces insulin resistance, elevating obesity risk by disrupting blood sugar regulation and fat storage. Stress also affects the gut microbiome, potentially influencing chronic inflammation and metabolic processes linked to obesity.

1. Mental Health, Pandemic Environment, and Eating Disorders

Stress is an element that forms the mental sphere of every human being, regardless of age, gender, stage of mental development, or social status. It has a chronic, relatively strong, and prolonged effect on the health and biopsychospiritual status of the individual, although it can also have an individually positive effect. It such a case, stress is called eustress, which generates a positive psychological response to the interacting stressors; this effect mainly depends on personal reasoning and definition of stress and its impact on well-being

[1][2][3][4][24,25,26,27].

The perception of stress by the child and adolescent is related to many factors, various social exposures, the transition between phases of psychomotor development, changes in health, family, and school situations, imposed restrictions, and peer relationships. It should be noted that, according to recent studies, a child from the age of 2 is aware of the changes occurring in their environment. Such changes include the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) virus pandemic and the associated reorganization of the environment, such as isolation, homeschooling, restrictions on peer relationships, health problems for children and adolescents themselves, as well as their loved ones and others, including the topics of dying and death

[5][6][7][28,29,30].

During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the occurrence of disorders related to food intake was observed in both children and adolescents. These included problems with appetite, choice of unhealthy foods, and changing dynamics in the development of previously diagnosed eating disorders. Some of the main elements associated with abnormal relationships with food are psychological and psychiatric aspects

[8][9][31,32]. The pandemic period has led to increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in children and adolescents, which accompany the aforementioned problems

[8][9][10][31,32,33].

Appetite disorders include a decrease, increase, or loss of the urge to take food. A study by Paiva et al. in Brazil found a statistically significant (

p < 0.001) association between the presence of anxiety in children (related, among other things, to social isolation during a pandemic) and the occurrence of appetite problems. The presence of anxiety in children translated into a 3.12-fold increased risk of changes in appetite, which in the majority was manifested by increased food intake

[11][34]. A study conducted in Spain by Lavigne-Cerván et al. found that more than half of the children and adolescents studied had moderate to high levels of anxiety, which coincided with the results of a study by Jiao et al. conducted in China that showed reduced or no appetite

[12][13][35,36]. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s guide to parents, published in 2020, highlighted the possibility of appetite-related disorders in children of all ages, indicating the nature of the problem

[14][37]. Appetite is influenced, alongside increasing anxiety, by depressive symptoms, which are a challenge during pandemics

[15][16][38,39]. Among children and adolescents suffering from depression, the majority show decreased or increased appetite, as well as weight disturbances

[17][18][19][40,41,42].

Choosing the right food is the basis for a healthy diet. Children’s and adolescents’ dietary choices are influenced by parental eating habits, household habits, and the environment

[20][43]. During the pandemic, access to smartphones, social isolation, and increasing stress led to the occurrence of dietary disorders. Increased intake of high-calorie foods, inter-meal snacking, and less frequent choice of healthy, low-calorie foods are caused by increasing stress and prolonged screen time

[21][22][23][24][44,45,46,47].

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition, there are three specific eating disorders: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED)

[25][48]. The number of diagnoses of these disorders among children and adolescents increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with AN being the predominant one. A cross-sectional study conducted in Canada by Agostino et al. confirmed a significant increase in new diagnoses of AN, rapid evaluation of disease markers, and hospitalizations for this condition

[26][27][28][49,50,51]. Moreover, during the pandemic, there was also an increase in hospitalizations due to bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders

[29][52].

It has to be highlighted that there is a mutual relationship between obesity and eating disorders, particularly bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder

[30][53]. Individuals with BED have a three to six times increased risk of obesity compared with the general population

[31][54]. Although patients with BN may have normal weight, the lifetime prevalence of obesity in this group is about 33%

[32][55]. In a cohort of Canadian adolescents, the prevalence of eating disorders was 9.3% in obese boys and 20.2% in obese girls compared with 2.1% and 8.4% of normal-weight boys and girls, respectively

[33][56].

Obesity and eating disorders share a common pathophysiology that involves biological, environmental, behavioral, and cognitive determinants

[30][34][53,57]. Possible shared genetic susceptibility for both disorders may be associated with at-mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene polymorphisms

[30][53]. Moreover, dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) and gut dysbiosis play an important role in the pathophysiology of obesity and eating disorders

[30][53]. Environmental risk factors identified for both disorders are, among others, weight teasing, internalization of unattainable beauty ideals portrayed on social media and television, social pressure and frequent criticism, bullying, and unhealthy family eating patterns

[30][34][53,57]. Psychological determinants that may play a significant role in the development of obesity and eating disorders may include low self-esteem, negative self-evaluation, and high body dissatisfaction

[30][53]. Body dissatisfaction, compromised interpersonal functioning, aberrant emotional regulation, and inappropriate weight control behaviors are also common factors contributing to both disorders

[30][34][53,57].

Disordered eating symptomatology was exacerbatedduring the pandemic and were more pronounced in adolescents than in younger children. Individuals at increased risk for developing these conditions were also observed to exhibit their exponents. These conditions were also observed to be exhibited by individuals at an increased risk of developing them. Circumstances that may have a role in triggering eating disorders include increasing anxiety, social isolation, and more time spent on social media. This often resulted in disturbances in the perception of one’s own body; excessive physical activity, fear of gaining weight, and inappropriate food intake were often observed as a result. These circumstances not only influenced the occurrence of eating disorder symptoms but also the motivation to recover

[9][35][36][37][32,58,59,60]. Family members spending more time together at home as a result of social distancing and lockdown requirements reflected increased parental recognition of eating disorder symptoms in children, which may have had an impact on the increase in acute ED visits and hospital admissions. Some patients and their families linked the onset of lockdown as a trigger for hospital admission. The overall increase in hospital admissions for eating disorder exacerbations and prolonged stays has resulted in an increased demand for care related to the treatment of these disorders

[38][39][40][61,62,63].

Table 1 provides information on the psychological and pedagogical interventions that are used in the treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents.

2. Prevention of Eating Disorders

In the face of the numerous described problems associated with stress-related eating disorders and obesity (covibesity) in a group of children and adolescents, preventive measures to counteract the psychosocial aspects that promote the development of these disorders become important.

The first group of recipients of the above-described measures should be the primary support system of the child or adolescent, namely the family environment. During the pandemic, adhering to the principles of social isolation, caregivers spent significantly more time at home, working remotely, supervising the learning of their offspring, and fulfilling the duties of daily life in the online system. As a result, adults became distanced from mundane pleasures and, consequently, a sense of disorganization, frustration, and anger was aroused, which was often unloaded on the child or adolescent

[47][48][49][70,71,72]. Heightened emotional reactions from the parent, such as excessive criticism and hostility, can consequently lead to the child developing an eating disorder in the form of malnutrition or compulsive overeating

[49][72]. Eating meals as a family can be a difficult psychological experience for a young person, and as a result, young people may restrict eating

[48][49][71,72]. Available studies describe the relationship between the qualitative support of caregivers and the risk of eating disorders in their children

[49][72]. In 2014, a program to support caregivers of people with eating disorders called Peer-Led Resilience (PiLAR) was introduced in Ireland. It was followed by an evaluation of its effects, which showed increased knowledge, skills, and improved psychological well-being of parents, positively influencing the quality of treatment and mental health of their children. Studies confirm the great importance of psychoeducation, self-help, and skills training in telepsychiatry systems in developing supportive attitudes of caregivers toward children with eating disorders and obesity

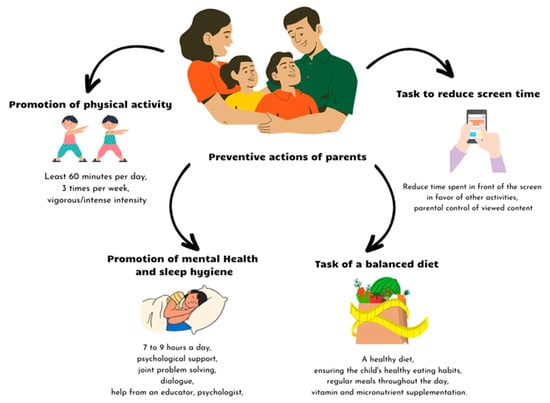

[49][50][72,73]. For obesity, possible preventive actions for parents are shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Possible covibesity prevention activities dedicated to parents [47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55]. Possible covibesity prevention activities dedicated to parents [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78].

Preventive actions aimed at children themselves are divided, according to the specialized literature, into two types: universal—carried out in all children regardless of the degree of assessed risk; selective—carried out in groups of high-risk children (e.g., dancers, athletes, and obese children)

[51][74]. A meta-analysis and systematic review conducted by Chua, Tam, and Shorey confirms the effectiveness of implementing eating disorder and obesity prevention activities in school settings. These interventions are primarily aimed at reducing the internalization of beauty ideals, and thereby increasing students’ self-esteem.

These interventions are based on psychoeducation, training in the use of social media, and interpersonal training with an emphasis on the phenomena of teasing by peers. The study also indicates that girls are more prone to these activities than boys, due to their greater susceptibility to generating the cognitive illusion of a bad body image

[52][75].

A major role in the prevention of eating disorders and obesity in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic is played by healthcare system workers, i.e., pediatricians, family physicians, and mental healthcare workers. Their roles and responsibilities are described in a narrative review by Singh et al.

[53][76]. Pediatricians and family physicians conducting a periodic examination of a child or adolescent can recognize physical symptoms of stress and the patient’s externalizing/internalizing emotional states. These professionals can then screen for mental disorders, including eating disorders and compulsive overeating, using brief, standardized screening tools such as the Children’s Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI-C); the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q); semi-structured interviews, such as the Children’s Eating Disorder Examination (ChEDE); and online measures, such as the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA)

[54][55][77,78]. The role of mental healthcare workers is to promote mental health (in the form of digital brochures, videos, etc., available online for caregivers, teachers, and children), increase mental health awareness and, most importantly, promote the practice of mental health hygiene

[15][53][38,76].