You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Tao Lu.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States, with an estimated 52,000 deaths in 2023. Though significant progress has been made in both diagnosis and treatment of CRC in recent years, genetic heterogeneity of CRC—the culprit for possible CRC relapse and drug resistance, is still an insurmountable challenge. Thus, developing more effective therapeutics to overcome this challenge in new CRC treatment strategies is imperative. Genetic and epigenetic changes are well recognized to be responsible for the stepwise development of CRC malignancy.

- CRC

- genetic alteration

- NF-κB

1. Known NF-κB Genetic Mutations in CRC

1.1. Genetic Alterations

As summarized in Table 1 [31[1][2],32], different components of NF-κB family members have various gene alterations, like mutations, deletion, amplification, etc., in CRC.

Table 1. Mutations observed on NF-κB components among 348 colon cancer patients (Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics) [31,32][1][2].

| Gene Symbol | Gene Description | Protein | Protein Mutation | Mutation Type | Copy Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rel | C-Rel proto-oncogene, NF-κB subunit | Rel | R22C | Missense | Diploid |

| G288S | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R108Q | Missense | Diploid | |||

| G229D | Missense | Diploid | |||

| X285_splice | Splice | Diploid | |||

| RelA | RelA proto-oncogene, NF-κB subunit | RelA (p65) | R166W | Missense | Diploid |

| D446H | Missense | Diploid | |||

| N139del | IF del | Diploid | |||

| H487Pfs*4 | FS ins | Diploid | |||

| P521L | Missense | Diploid | |||

| T357A | Missense | Diploid | |||

| Q287* | Nonsense | ShallowDel | |||

| RelB | RELB Proto-Oncogene, NF-κB Subunit | RelB | A29V | Missense | Diploid |

| P314L | Missense | Gain | |||

| R434W | Missense | Diploid | |||

| T494M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| G530Afs*5 | FS del | Diploid | |||

| E53* | Nonsense | Diploid | |||

| P482L | Missense | Diploid | |||

| P482L | Missense | ShallowDel | |||

| V379I | Missense | Diploid | |||

| G522R | Missense | Diploid | |||

| Y539H | Missense | Diploid | |||

| V353M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| C306Y | Missense | Diploid | |||

| NF-κB1 | NF-κB subunit 1 | p105/p50 | R613C | Missense | Diploid |

| A901T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| G477V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| D436G | Missense | Diploid | |||

| NF-κB2 | NF-κB subunit 2 | p100/p52 | Y294Ifs*4 | FS del | Diploid |

| A514T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A867V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| K252N | Missense | Diploid | |||

| T806M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L474M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A121T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| K252M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| M1? | Nonstart | Diploid |

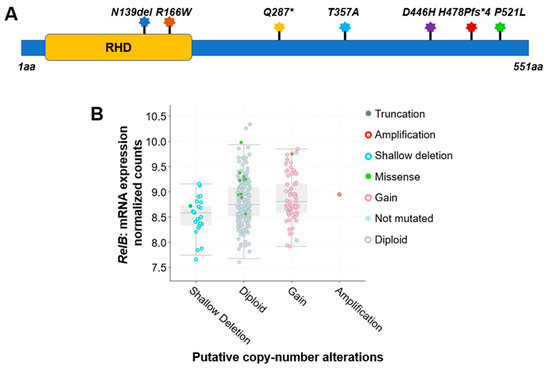

For instance, a comprehensive analysis of 348 colon cancer samples revealed that approximately 2.5% of the cases exhibited gene alterations in the RelA protein. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1A, seven different types of protein mutations have been identified on RelA, the large subunit of NF-κB, in 348 CRC patients. They are R166W (Arginine–Tryptophan mutation), D446H (Aspartic acid–Histidine mutation), N139del (Asparagine deletion), etc. These mutations include missense, deletion, insertion, or nonsense mutations. The copy number of gene is either diploid, or shallow deletion. Among these mutations, two are located in the rel homology domain (RHD) (Figure 3A), which mediates the crucial function of DNA contact and homo- and heterodimerization.

Figure 1. Genetic alterations on NF-κB family members RelA and RelB. (A) Schematic diagram of protein mutations on RelA identified in CRC patients. Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [31,32][1][2]. Note: RelA is 551 amino acids (aa) in length. Abbreviation: RHD: Rel homology domain. (B) Putative copy number alterations from Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer (GISTIC) for RelB. Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [31,32][1][2]. Symbol *: Nonsense mutations.

Interestingly, compared to the RelA protein, another NF-κB family member, RelB, exhibited more frequency of gene alterations. The analysis of 348 colon cancer samples revealed that approximately 5% of the cases exhibited gene alteration in the RelB protein. As shown in Table 1, more than a dozen various types of protein mutations have been identified on RelB in 348 CRC patients. They are P314L (Proline–Leucine mutation), T494M (Threonine–Methionine mutation), Y539H (Tyrosine–Histidine mutation), etc. These mutations include missense, deletion, or nonsense mutations. The copy number of gene is diploid, gain, shallow deletion, or amplification (Table 1, Figure 3B).

Other NF-κB family members, like Rel, NF-κB1, and NF-κB2, have been identified with various types of gene alterations. The overall mutation types identified among important NF-κB signaling components are listed in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 (Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics) [31,32][1][2]. For instance, the protein mutations types identified for Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-κB1, and NF-κB2 are 5, 7, 13, 4, and 9, with a total number of 38 protein mutation variants identified (Table 3). The gene alteration frequencies are in the same order, 2.5, 2.5, 5.0, 1.8, and 3.0%, respectively, with a total 14.8% alteration frequency among these 5 NF-κB family members. These data suggest the high genetic alteration rate of NF-κB family members in CRC patients, highlighting the genetic heterogeneity of NF-κB family members alterations in CRC, and suggesting potential implications for the proteins’ functional activities in CRC.

Table 2. Mutations observed on regulators of the NF-κB signaling pathway among 348 colon cancer patients (Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics) [31,32][1][2].

| Gene Symbol | Gene Description | Protein | Protein Mutation | Mutation Type | Copy Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuk (IKBKA) | Inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase subunit α | IKKα | E82* | Nonsense | Diploid |

| P700del | IF del | Diploid | |||

| X577_splice | Splice | Diploid | |||

| E513* | Nonsense | Diploid | |||

| L50P | Missense | ShallowDel | |||

| IKBKB | Inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase subunit β | IKKβ | R582Q | Missense | Diploid |

| P551L | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A454T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| N225Tfs*25 | FS del | Gain | |||

| Q438H | Missense | Gain | |||

| A481V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| X159_splice | Splice | Gain | |||

| IRAK1 | Interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 1 | IRAK1 | R51C | Missense | Diploid |

| T383A | Missense | Diploid | |||

| T234M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A78T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R61C | Missense | Diploid | |||

| E259D | Missense | Diploid | |||

| C43R | Missense | Diploid | |||

| KDM2A | Lysine demethylase 2A | KDM2A | P597Afs*34 | FS ins | Diploid |

| T162M | Missense | Diploid | |||

| N1083S | Missense | Diploid | |||

| H452R | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A576S | Missense | Diploid | |||

| P729L | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R733G | Missense | Diploid | |||

| S416G | Missense | Diploid | |||

| MAP3K7 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | MAP3K7 (TAK1) | R226W | Missense | Diploid |

| T169Dfs*7 | FS ins | Diploid | |||

| R238Q | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L255V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| D488V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R248Q | Missense | Diploid | |||

| P256S | Missense | Diploid | |||

| D343Y | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R463K | Missense | Diploid | |||

| NFKBIA | NF-κB inhibitor α | IκBα | E41A | Missense | Diploid |

| P147H | Missense | Diploid | |||

| ODAD2 | Outer dynein arm docking complex subunit 2 | ODAD2 | T9M | Missense | Diploid |

| R841C | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R1032C | Missense | Diploid | |||

| K304T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| I517T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L813I | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A29V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A556V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L298* | FS del | Gain | |||

| E626* | Nonsense | Diploid | |||

| I543T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A445E | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L154I | Missense | Diploid | |||

| G536D | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A820S | Missense | ShallowDel | |||

| S661A | Missense | Diploid | |||

| S743Y | Missense | Diploid | |||

| PRMT5 | Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 | PRMT5 | H47Y | Missense | Diploid |

| V413L | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R256Q | Missense | Diploid | |||

| Y535S | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L287V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| E57K | Missense | Gain | |||

| TAB1 | TGFβ activated kinase 1 (MAP3K7) binding protein 1 | TAB1 | Y293C | Missense | Diploid |

| E96D | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A310G | Missense | Diploid | |||

| L361Q | Missense | Diploid | |||

| TAB2 | TGF-β activated kinase 1 (MAP3K7) binding protein 2 | TAB2 | A672T | Missense | Diploid |

| R579I | Missense | Diploid | |||

| N211K | Missense | Diploid | |||

| R72C | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A182V | Missense | Diploid | |||

| TRAF2 | TNF receptor associated factor 2 | TRAF2 | P9Lfs*77 | FS del | Diploid |

| P9Lfs*77 | FS del | Amp | |||

| E122K | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A3T | Missense | Diploid | |||

| A494V | Missense | Diploid |

Table 3. Protein Mutation Rate of NF-κB family members or representative NF-κB pathway regulators among 348 CRC patients (Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics) [31,32][1][2].

| Classification | Protein | Protein Mutation Types | Alteration Frequency, % | Total Protein Mutation Types | Total Alteration Frequency, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB family members | Rel | 5 | 2.5 | 38 | 113 | 14.8 | 53.7 |

| RelA (p65) | 7 | 2.5 | |||||

| RelB | 13 | 5.0 | |||||

| P105/p50 | 4 | 1.8 | |||||

| P100/p52 | 9 | 3.0 | |||||

| NF-κB pathway regulators | IKKα | 5 | 1.4 | 75 | 38.9 | ||

| IKKβ | 7 | 6.0 | |||||

| IRAK1 | 7 | 4.0 | |||||

| KDM2A | 8 | 2.8 | |||||

| MAP3K7 | 9 | 4.0 | |||||

| NFKBIA | 2 | 1.1 | |||||

| ODAD2 | 17 | 7.0 | |||||

| PRMT5 | 6 | 5.0 | |||||

| TAB1 | 4 | 1.8 | |||||

| TAB2 | 5 | 3.0 | |||||

| TRAF2 | 5 | 2.8 | |||||

1.2. Polymorphism in the NF-κB1 Gene in CRC

In addition to protein mutations among NF-κB family members, other genetic changes, such as polymorphism have also been linked to CRC progression. Despite the fact that NF-κB can form various pairs of molecules, the prototypical one is the heterodimer of p65 (RelA)/p50. p50 is coded by the NF-κB1 gene on chromosome 4q23-q24. This p65/p50 heterodimer plays a key role in NF-κB function [33,34,35][3][4][5]. In several cancer types, including CRC, lung cancer, blood cancer, and pancreatic cancer, etc., researchers have observed constitutive activation of this particular family [36,37,38,39][6][7][8][9].

Importantly, a recent study has detected a genetic variation within the promoter segment of the NF-κB1 gene. This genetic variation entails a 4-base pair (bp) insertion/deletion (94ins/delATTG) positioned between two presumed critical regulatory components in the promoter, specifically AP-1 and κB [36][6]. Interestingly, the research found that people who have two copies of this deletion (94del/delATTG) are more likely to develop ulcerative colitis, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease predominantly affecting the colon. If left untreated, ulcerative colitis-related inflammation in the colon can result in an increased risk in developing CRC. The study observed that the deletion variant of the 94ins/delATTG polymorphism in the NF-κB1 gene’s promoter region, whether homozygous (DD) or heterozygous (WD), was linked to an increased risk in CRC among Swedish patients, including those with both unselected and sporadic forms of the disease [36,40][6][10].

Taken together, numerous evidences have demonstrated the high mutation rate of NF-κB family members in CRC. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the specific biological significance and clinical implications of these diverse NF-κB mutations and mRNA expression patterns in the context of CRC progression and treatment response. Such insights may provide valuable avenues for targeted therapies and personalized approaches in managing CRC patients with these specific molecular features.

2. Known Genetic Changes of NF-κB Signaling Regulators

2.1. Overall Genetic Alterations

In addition to the NF-κB family members mentioned above, there are many known NF-κB signaling pathway regulators that may harbor genetic alterations in CRC patients as well. It is worth noting that both negative regulators of NF-κB subject to loss-of-function mutations or positive regulators of NF-κB affected by gain-of-function mutations may lead to NF-κB constitutive activation.

As shown in Table 2, representative positive regulators such as Inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase subunit α (Chuk, also named IKBKA), Inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase subunit β (IKBKB), Interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 1 (IRAK1), Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 (MAP3K7), Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) [34[4][11][12][13],41,42,43], TGFβ activated kinase (MAP3K7) binding protein 1 (TAB1), TAB2, and Tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2 (TRAF2) have 5, 7, 7, 9, 6, 4, 5, and 5 different types of protein mutation variants, respectively. In the same order, their individual genetic alteration frequencies are 1.4, 6.0, 4.0, 4.0, 5.0, 1.8, 3.0, and 2.8% (Table 2 and Table 3) (Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics) [31[1][2],32], with IKBKB and PRMT5 having the top 2 gene alteration frequency.

In terms of negative regulators, such as Lysine demethylase 2A (KDM2A, also named F-box and leucine-rich repeat 11, FBXL11) [35[5][9],39], NF-κB inhibitor α (NFKBIA, also named IκBα), and Outer dynein arm docking complex subunit 2 (ODAD2, also named armadillo repeat-containing 4, ARMC4) [44][14], they have 8, 2, and 17 different types of mutant variants. Accordingly, their genetic alteration frequencies are 2.8, 1.1, and 7.0%, among which ODAD2 has the most diverse mutants and highest genetic alteration frequency (Table 2 and Table 3).

Together, there are total 75 protein mutation types and 38.9% of genetic alteration frequency in these representative NF-κB positive and negative regulators. With additional 38 mutation types, and 14.8% genetic alteration frequency of NF-κB family members, it consists of a strikingly high number of mutation types (113 types) and high frequency (~53.7%) of genetic alterations in these 348 CRC patients studied (Table 3). In addition to the representative NF-κB regulators listed in Table 2, there are more NF-κB pathway regulators that are not included in Table 2, like myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), IKKγ, TNFα induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, also named A20), TNF receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 1 (TRAF1), TRAF6, etc. Thus, the percentage of genetic alterations from factors that can affect NF-κB signaling shall be much more than the 53.7%. Therefore, the clinical data from these 348 CRC patients strongly suggest the pivotal role of genetic variations in both NF-κB family members and NF-κB pathway regulators may play in CRC initiation, progression, and prognosis [32][2].

2.2. Genetic Alterations of NF-κB Positive Regulator, PRMT5 in CRC

PRMT5, a type II PRMT enzyme, regulates gene expression, cell cycle, and protein function through arginine methylation [45][15]. PRMT5 is a critical player in various cancer types, including colorectal cancer, and its increased expression is common in these malignancies [34,41,42,43,46,47][4][11][12][13][16][17]. Overexpression in colorectal cancer suggests its role in oncogenesis via epigenetics and cell cycle, highlighting the potential for targeted therapy [43,45][13][15]. PRMT5 mutations are prevalent across a spectrum of cancer types, with a pronounced prevalence notably in CRC, pancreatic cancer, etc. This underscores their substantive role in the pathogenesis of these specific cancers, suggesting their potential as pivotal drivers [45][15]. Consequently, understanding the prevalence and significance of PRMT5 mutations holds promise for informing novel therapeutic interventions targeting the molecular underpinnings of skin and colorectal cancer. Notably, among the PRMT1-9 genes, PRMT5 gene is unique due to its higher occurrence of missense mutations. This suggests that changes in the coding sequence of PRMT5 are more frequent in cancers, implying a potential role in cancer development [48][18]. Based on an analysis employing the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC), a comprehensive collection indicates a total of 338 PRMT5 mutations across various cancer types. Among these, 239 mutations are positioned in coding regions, while 99 are located in non-coding regions [48][18].

Ongoing extensive research is dedicated to deciphering the intricate mechanisms by which PRMT5 influences tumor formation, offering promising avenues for developing targeted and effective cancer treatments. PRMT5 has been previously shown to be overexpressed in approximately 75% of CRC patient tumor samples and negatively correlated with CRC patient survival. PRMT5 catalyzes the methylations of some proteins including NF-κB and Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), both are key transcriptional and translational regulators widely recognized as oncogenic drivers in various solid tumors, including CRC [49,50][19][20]. A study has shown the impact of the Serine–Alanine mutant of PRMT5 (S15A) in HEK293 and CRC cells (HT29, DLD1, and HCT116) to understand its effect on NF-κB activation [49][19]. The results confirmed that S15 phosphorylation is crucial for PRMT5-mediated NF-κB activation. Overexpressing the S15A mutant significantly reduced NF-κB activation, indicating its inhibitory role. Moreover, the mutation disrupted the interaction between PRMT5 and p65 and led to decreased PRMT5 methyltransferase activity upon IL-1β stimulation.

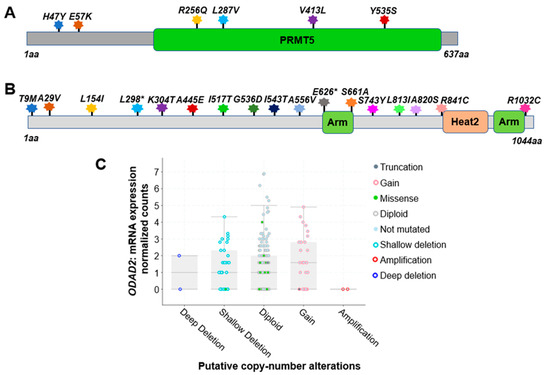

Based on the analysis of 348 colon cancer patient samples using data from the CBioPortal [31[1][2],32], approximately 5.0% were found to harbor genetic alterations on the PRMT5 gene. Among these, six notable missense mutations were identified. They are H47Y (Histidine–Tyrosine); E57K (Glutamate–Lysine); R256Q (Arginine–Glutamine); L287V (Leucine–Valine); V413L (Valine–Leucine), and Y535S (Tyrosine–Serine) (Figure 2A). All of these are missense mutations. Additionally, there are cases of gene copy number gain.

Figure 2. Genetic alterations on NF-κB signaling regulators PRMT5 and ODAD2. (A) Schematic diagram of protein mutations on PRMT5 identified in CRC patients. Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [31,32][1][2]. Note: PRMT5 is 637 amino acids (aa) in length. (B) Schematic diagram of protein mutations on ODAD2 identified in CRC patients. Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [31,32][1][2]. Note: ODAD2 is 1044aa in length. Note: Arm, Heat2 are domains on ODAD2. (C) Putative copy number alterations from GISTIC for ODAD2. Data resource: cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics [31,32][1][2]. Symbol *: Nonsense mutations.

This finding highlights the genetic heterogeneity within the studied population. The specific missense mutations at the residues listed above suggest potential functional implications that may contribute to the pathobiology of CRC. Further investigation into the consequences of this mutation and its role in tumorigenesis could offer valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying CRC, potentially paving the way for targeted therapeutic approaches in personalized treatment strategies for affected patients [31,32][1][2].

In fact, PRMT5 currently is viewed as a hot therapeutic target in cancer. Several pharmaceutical companies are developing inhibitors to target this enzyme [42,43][12][13].

2.3. Genetic Alterations of NF-κB Negative Regulator, ODAD2 in CRC

Recently, using the powerful validation-based insertional mutagenesis (VBIM) technique established by a laboratory previously [39,44][9][14], it is discovered outer dynein arm docking complex subunit 2 (ODAD2) (also named armadillo repeat-containing protein 4 (ARMC4), a rarely studied protein known to date, as a novel negative regulator of NF-κB in CRC. A high expression of ODAD2 downregulated the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes, dramatically reduced NF-κB activity, cellular proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, and migratory ability in vitro, and significantly decreased xenograft tumor growth in vivo. Importantly, the lower ODAD2 expression in patient tumors than normal tissues indicate its potential tumor suppressor function in CRC.

Impressively, based on the analysis of 348 colon cancer patient samples using data from the CBioPortal [31,32][1][2], approximately 7.0% of patients were found to harbor genetic alterations of ODAD2 (Table 3). Among these, 17 notable protein mutations were identified. For instance, mutations include L298* FS del (Leucine frame shift deletion), A556V (Alanine–Valine), and A820S (Alanine–Serine) missense mutation with ShallowDel (Shallow deletion), etc. (Figure 2B, Table 2). The types of gene alterations include missense mutation, deep deletion, amplification, etc. (Figure 2C). These data suggest that genetic alteration in ODAD2 could be an important factor contributing to CRC initiation and progression.

References

- CBioPortal for Cancer Genomics. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=coad_silu_2022 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Roelands, J.; Kuppen, P.J.K.; Ahmed, E.I.; Mall, R.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, P.; Monaco, G.; Raynaud, C.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C.; Ferraro, L.; et al. An Integrated Tumor, Immune and Microbiome Atlas of Colon Cancer. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1273–1286.

- Chen, F.; Castranova, V.; Shi, X.; Demers, L.M. New Insights into the Role of Nuclear Factor-KappaB, a Ubiquitous Transcription Factor in the Initiation of Diseases. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 7–17.

- Wei, H.; Wang, B.; Miyagi, M.; She, Y.; Gopalan, B.; Huang, D.B.; Ghosh, G.; Stark, G.R.; Lu, T. PRMT5 Dimethylates R30 of the p65 Subunit to Activate NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13516–13521.

- Lu, T.; Jackson, M.W.; Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Chance, M.R.; Miyagi, M.; Gudkov, A.V.; Stark, G.R. Regulation of NF-kappaB by NSD1/FBXL11-Dependent Reversible Lysine Methylation of p65. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 46–51.

- Alidoust, M.; Shamshiri, A.K.; Tajbakhsh, A.; Gheibihayat, S.M.; Mazloom, S.M.; Alizadeh, F.; Pasdar, A. The Significant Role of a Functional Polymorphism in the NF-κB1 Gene in Breast Cancer: Evidence from an Iranian Cohort. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 4895–4905.

- Weichert, W.; Boehm, M.; Gekeler, V.; Bahra, M.; Langrehr, J.; Neuhaus, P.; Denkert, C.; Imre, G.; Weller, C.; Hofmann, H.-P.; et al. High Expression of RelA/p65 is Associated with Activation of Nuclear Factor-κB-Dependent Signaling in Pancreatic Cancer and Marks a Patient Population with Poor Prognosis. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97, 523–530.

- Lu, T.; Sathe, S.S.; Swiatkowski, S.M.; Hampole, C.V.; Stark, G.R. Secretion of Cytokines and Growth Factors as a General Cause of Constitutive NFkappaB Activation in Cancer. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2138–2145.

- Nagel, D.; Vincendeau, M.; Eitelhuber, A.C.; Krappmann, D. Mechanisms and consequences of constitutive NF-κB activation in B-cell lymphoid malignancies. Oncogene 2014, 33, 5655–5665.

- Lewander, A.; Butchi, A.K.R.; Gao, J.; He, L.-J.; Lindblom, A.; Arbman, G.; Carstensen, J.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; The Swedish Low-Risk Colorectal Cancer Study Group; Sun, X.-F. Polymorphism in the Promoter Region of the NFKB1 Gene Increases the Risk of Sporadic Colorectal Cancer in Swedish but Not in Chinese Populations. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42, 1332–1338.

- Lu, T.; Stark, G.R. NF-κB: Regulation by Methylation. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3692–3695.

- Prabhu, L.; Martin, M.; Chen, L.; Demir, Ö.; Jin, J.; Huang, X.; Motolani, A.; Sun, M.; Jiang, G.; Nakshatri, H.; et al. Inhibition of PRMT5 by Market Drugs as a Novel Cancer Therapeutic Avenue. Genes Dis. 2022, 10, 267–283.

- Prabhu, L.; Wei, H.; Chen, L.; Demir, Ö.; Sandusky, G.; Sun, E.; Wang, J.; Mo, J.; Zeng, L.; Fishel, M.; et al. Adapting AlphaLISA High Throughput Screen to Discover a Novel Small-Molecule Inhibitor Targeting Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 in Pancreatic and Colorectal Cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 39963–39977.

- Martin, M.; Mundade, R.; Hartley, A.V.; Jiang, G.; Jin, J.; Sun, S.; Safa, A.; Sandusky, G.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T. Using VBIM Technique to Discover ARMC4/ODAD2 as a Novel Negative Regulator of NF-κB and a New Tumor Suppressor in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2732.

- Abumustafa, W.; Zamer, B.A.; Khalil, B.A.; Hamad, M.; Maghazachi, A.A.; Muhammad, J.S. Protein Arginine N-Methyltransferase 5 in Colorectal Carcinoma: Insights into Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112368.

- Shifteh, D.; Sapir, T.; Pahmer, M.; Haimowitz, A.; Goel, S.; Maitra, R. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 as a Therapeutic Target for KRAS Mutated Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2091.

- Wei, H.; Hartley, A.V.; Motolani, A.; Jiang, G.; Safa, A.; Prabhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T. A Complex Signature Network That Controls the Upregulation of PRMT5 in Colorectal Cancer. Genes Dis. 2021, 9, 285–287.

- Rasheed, S.; Bouley, R.A.; Yoder, R.J.; Petreaca, R.C. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) Mutations in Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6042.

- Hartley, A.V.; Wang, B.; Jiang, G.; Wei, H.; Sun, M.; Prabhu, L.; Safa, A.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T. Regulation of a PRMT5/NF-κB Axis by Phosphorylation of PRMT5 at Serine 15 in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3684.

- Hartley, A.V.; Wang, B.; Mundade, R.; Jiang, G.; Sun, M.; Wei, H.; Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T. PRMT5-Mediated Methylation of YBX1 Regulates NF-κB Activity in Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15934.

More