Prenatal alcohol exposure is one of the major avoidable causes of developmental disruption and health abnormalities in children. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), a significant consequence of prenatal alcohol exposure, have gained more attention. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are an umbrella term used to describe a pattern of disabilities and abnormalities that result from fetal exposure to ethanol during pregnancy and are the most common non-heritable causes of intellectual disability. The effects on the fetus may include physical, mental, behavioral, and/or learning disabilities, with possible lifelong implications, and encompass a phenotypic range that can greatly vary between individuals but reliably include one or more of the following: facial dysmorphism, fetal growth deficiency, central nervous system dysfunction, and neurobehavioral impairment.

- fetal alcohol syndrome

- fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- prenatal alcohol exposure

- alcohol consumption

- pregnancy

1. The Concept of FASD

2. Epidemiology

Despite many public education programs regarding alcohol consumption during pregnancy, the percentage of pregnant women consuming alcohol is increasing. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, alcohol consumption in pregnant women increased from 7.6% in 2012 to 10.2% in 2015 [10][1]. Furthermore, the number of pregnant women reporting binge drinking (four or more alcoholic beverages at once) increased from 1.4% to 3.1% [10][1]. In addition, data from the 2009 National Birth Defects Prevention Study of over 4000 women indicate that 30% of pregnant women use alcohol and 8% engage in binge drinking on at least one occasion [4]. High rates of alcohol consumption during pregnancy allow us to suspect a high prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. The global prevalence of FASDs in children and youth in the general population is 7.7 per 1000 people. The highest prevalence ratio is in the European Region (19.8 per 1000 people) [14][5]. One study in the US indicated that 1.1 to 5% (depending on the community) of first-graders have FASDs, and the weighted prevalence estimates for FASDs in this population ranged from 31.1 to 98.5 per 1000 children [15][6].3. Burden of FASDs

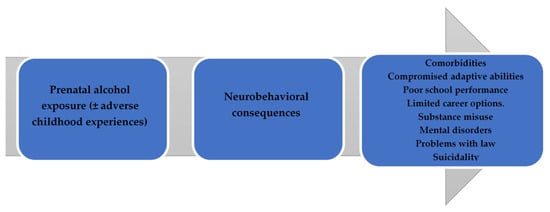

FASDs have an impact on various individual and social aspects. The outcomes caused by FASDs can be divided into primary and secondary disabilities. Primary disabilities comprise congenital conditions caused by the teratogenic effects of alcohol on the fetus’s brain and differences in behavior and cognition [16][7]. Delayed growth and craniofacial anomalies, including palpebral fissures, a smooth philtrum, and a thin upper lip vermilion, though infrequent, can help in terms of differential diagnoses [17][8]. In addition, FASDs have an increased risk of comorbidities, with ADHD, depression, anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and receptive as well as expressive language disorders being commonly reported [18][9]. FASDs have been associated with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which begin with prenatal alcohol exposure and tend to continue across the lifespan. In one systematic review, it was estimated that ADHD had the highest prevalence of 50% among individuals diagnosed with FASDs [19][10]. The impairments described above as well as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can increase the risk of comorbidities. FASDs and subsequent exposure to ACEs, with neglect, parental substance abuse, parental separation or divorce, and physical abuse being the most prevalent, can lead to the development of additional neurobehavioral disorders. Moreover, children with FASDs living in foster care exhibited higher ACE scores than non-FASD subjects (RR = 9.05). Children diagnosed with FASDs were 9 times more likely to be placed in foster care and 6.7 times more likely to be placed in residential care compared with controls [20,21][11][12]. Secondary disabilities may include poorer school performance, unemployment, needing support from social welfare, an increase in psychiatric and medical comorbidities, problems with the law, and victimization [16,22][7][13]. Problems with the justice system, victimization, and incarceration may also be relevant to FASDs [22][13]. Disruptions in adaptive functioning, including poor communication and social and daily living skills, as well as an inability to properly regulate behavior and emotions, can lead to daily challenges at school, home, and community environments, increasing the risk of disrupted school experiences, alcohol or drug addictions, inappropriate sexual behavior, and a reduced capacity to live independently [16][7]. Primary and secondary disabilities make significant demands of foster parents, birth parents, schools, mental health care systems, and legal institutions [22][13]. The biopsychosocial burden of FASDs is summarized in Figure 1.

4. Assessing Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

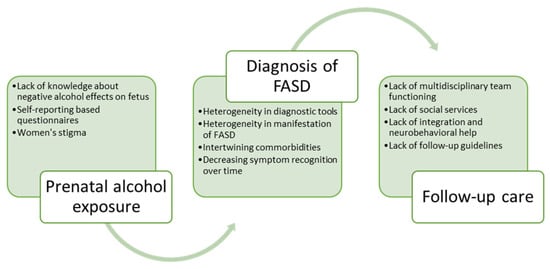

Documented prenatal alcohol exposure is a core component in making an FASD diagnosis. To effectively address alcohol consumption during pregnancy, an appropriate assessment of alcohol use as a routine component of prenatal care is essential. Many alcohol assessment tools in reproductive-age women and during pregnancy have been proposed (for example, CAGE, TWEAK, AUDIT-C, T-ACE, and T-ACER3) [23][14]. The biggest concern regarding such tools is their reliance on direct questioning and self-reporting, thus being prone to under-detection due to women’s unwillingness to admit to acts of alcohol consumption. Women who use substances during their pregnancies feel fear and stigma and, thus, are less willing to cooperate with physicians and more likely to avoid treatment [24][15]. The situation can be even more complicated in cases of maternal polysubstance abuse. There are efforts to create biomarkers that may be more valid than maternal self-reports. For example, one systematic review found that the detection of fatty acid ethyl esters in meconium indicated a more than four times higher prevalence of prenatal alcohol exposure compared with maternal self-reporting [25][16]. The latter findings indicate that maternal self-reports regarding PAE may not be sufficient as a sole information source [3,7][17][18].5. Recognition of Signs over Time

Children with dysmorphic features of FASDs can be identified as early as 9 months of age, with a peak of identification at 18 months of age compared with an unaffected group of children. However, children with severe impairment of dysmorphic features can be identified at birth. The literature notes that although early behavioral and development impairment is usually noted between 18 and 42 months of age, CNS impairment may not be apparent until the child is in school [26][19]. Thus, early childhood assessment appears the most sensitive, as well as providing sometimes the only evidence of FASD phenotypes. Children with FASD phenotypes can be missed if they do not have an assessment of the disorder in time, primarily due to the diminishing prevalence of short palpebral features and a small head circumference, as well as the physical features of prenatal alcohol exposure being absent in as many as 75% of affected children [27][20]. This statement is supported by a US study highlighting that without early childhood screening, only one in seven children will be identified later in their lifetime. Therefore, this confirms the importance of early screening before children start pre- or primary school as early interventions are the most effective in improving children’s future quality of life [28][21].6. Challenges in Follow-Up Care

Neurocognitive habilitation therapy and social skills improvement programs are especially recommended for patients with an FASD diagnosis. An effective neurocognitive habilitation program is “Alert” [29][22]. During the program, patients are encouraged to work in groups and introduced to learning concepts, creative activities, and the acknowledgment of sensory functions. Therefore, children learn to adapt to the community. If needed, medications can be administered (e.g., in the case of ADHD, depression, and anxiety disorders). Parents should also be educated on communicating with their children. Other interventions that aim to help patients to adapt may also be effective. For example, an analysis of one intervention, “MILE” (The Math Interactive Learning Experience), showed a significant gain in the patient’s math skills and behavior; another intervention, called “CFT” (Child Friendship Training), improves social skills, whereas “CPAT” (Computerized Progressive Attention Training) decreases reaction times and improves attention spans [30][23]. Cognitive control therapy significantly changes a child’s behavior. It teaches self-regulation, self-observation, and different thinking. The management of other comorbidities is chosen by a multidisciplinary team depending on the specific patient. Usually, a multidisciplinary team combines an audiologist, cardiologist, developmental pediatrician, developmental therapies, family therapist, nephrologist, neurologist, occupational therapist, ophthalmologist, physical therapist, primary care physician, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, sensory integration therapist, social worker, special education teachers, and speech-language pathologist. The literature shows that the lack of a functioning multidisciplinary team arises from the absence of FASD follow-up guidelines and neuropsychological help, and patients are left without proper care [2,3,10][1][17][24]. A summary of the challenges in evaluating prenatal alcohol exposure, diagnosing FASDs, and providing adequate care afterward is presented in Figure 2.

References

- Denny, L.; Coles, S.; Blitz, R. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 515–522.

- Children and Young People Exposed Prenatally to Alcohol: A National Clinical Guideline—Digital Collections—National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://digirepo.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101772266-pdf (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Hoyme, H.E.; May, P.A.; Kalberg, W.O.; Kodituwakku, P.; Gossage, J.P.; Trujillo, P.M.; Buckley, D.G.; Miller, J.H.; Aragon, A.S.; Khaole, N.; et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 39–47.

- Ethen, M.K.; Ramadhani, T.A.; Scheuerle, A.E.; Canfield, M.A.; Wyszynski, D.F.; Druschel, C.M.; Romitti, P.A.; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Alcohol Consumption by Women Before and During Pregnancy. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 274–285.

- Lange, S.; Probst, C.; Gmel, G.; Rehm, J.; Burd, L.; Popova, S. Global Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder among Children and Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. Pediatr. 2017, 171, 948–956.

- May, P.A.; Chambers, C.D.; Kalberg, W.O.; Zellner, J.; Feldman, H.; Buckley, D.; Kopald, D.; Hasken, J.M.; Xu, R.; Honerkamp-Smith, G.; et al. Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in 4 US Communities. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 319, 474–482.

- Rangmar, J.; Hjern, A.; Vinnerljung, B.; Strömland, K.; Aronson, M.; Fahlke, C. Psychosocial outcomes of fetal alcohol syndrome in adulthood. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e52–e58.

- Wozniak, J.R.; Riley, E.P.; Charness, M.E. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 760–770.

- Mattson, S.N.; Bernes, G.A.; Doyle, L.R. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A Review of the Neurobehavioral Deficits Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 1046–1062.

- Weyrauch, D.; Schwartz, M.; Hart, B.; Klug, M.G.; Burd, L. Comorbid Mental Disorders in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2017, 38, 283–291.

- Willoughby, K.A.; Sheard, E.D.; Nash, K.; Rovet, J. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on hippocampal volume, verbal learning, and verbal and spatial recall in late childhood. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2008, 14, 1022–1033.

- Kambeitz, C.; Klug, M.G.; Greenmyer, J.; Popova, S.; Burd, L. Association of adverse childhood experiences and neurodevelopmental disorders in people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and non-FASD controls. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 498.

- Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Esposito, M.; Di Nunno, N.; Rosi, G.L.; Roccuzzo, S.; Pomara, C. Understanding the Relationship between Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) and Criminal Justice: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 84.

- Jones, T.B.; Bailey, B.A.; Sokol, R.J. Alcohol use in pregnancy: Insights in screening and intervention for the clinician. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 56, 114–123.

- Stone, R. Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health Justice 2015, 3, 2.

- Lange, S.; Shield, K.; Koren, G.; Rehm, J.; Popova, S. A comparison of the prevalence of prenatal alcohol exposure obtained via maternal self-reports versus meconium testing: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 127.

- Gupta, K.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Shirasaka, T. An Update on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome-Pathogenesis, Risks, and Treatment. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 1594–1602.

- Popova, S.; Dozet, D.; Shield, K.; Rehm, J.; Burd, L. Alcohol’s Impact on the Fetus. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3452.

- Kalberg, W.O.; May, P.A.; Buckley, D.; Hasken, J.M.; Marais, A.-S.; De Vries, M.M.; Bezuidenhout, H.; Manning, M.A.; Robinson, L.K.; Adam, M.P.; et al. Early-Life Predictors of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics 2019, 14, e20182141.

- Jacobson, S.W.; Hoyme, H.E.; Carter, R.C.; Dodge, N.C.; Molteno, C.D.; Meintjes, E.M.; Jacobson, J.L. Evolution of the Physical Phenotype of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders from Childhood through Adolescence. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 395–408.

- Clarren, S.K.; Randels, S.P.; Sanderson, M.; Fineman, R.M. Screening for fetal alcohol syndrome in primary schools: A feasibility study. Teratology 2001, 63, 3–10.

- Wells, A.M.; Chasnoff, I.J.; Schmidt, C.A.; Telford, E.; Schwartz, L.D. Neurocognitive Habilitation Therapy for Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: An Adaptation of the Alert Program®. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 24–34.

- Reid, N.; Dawe, S.; Shelton, D.; Harnett, P.; Warner, J.; Armstrong, E.; LeGros, K.; O’Callaghan, F. Systematic Review of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Interventions across the Life Span. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 2283–2295.

- Pruett, D.; Waterman, E.H.; Caughey, A.B. Fetal alcohol exposure: Consequences, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2013, 68, 62–69.