Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an extremely devastating neurodegenerative disease, and there is no cure for it. AD is specified as the misfolding and aggregation of amyloid-β protein (Aβ) and abnormalities in hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Current approaches to treat Alzheimer’s disease have had some success in slowing down the disease’s progression. Chaperone proteins act as molecular caretakers to facilitate cellular homeostasis under standard conditions. Chaperone proteins like heat shock proteins (Hsps) serve a pivotal role in correctly folding amyloid peptides, inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction, and peptide aggregation. For instance, Hsp90 plays a significant role in maintaining cellular homeostasis through its protein folding mechanisms.

- Alzheimer’s disease

- amyloid-β protein

- Hsp90

- BRICHOS domain chaperone

- chemical chaperone

1. Introduction

2. Hsp90

2.1. Hsp90–LA1011 Complex

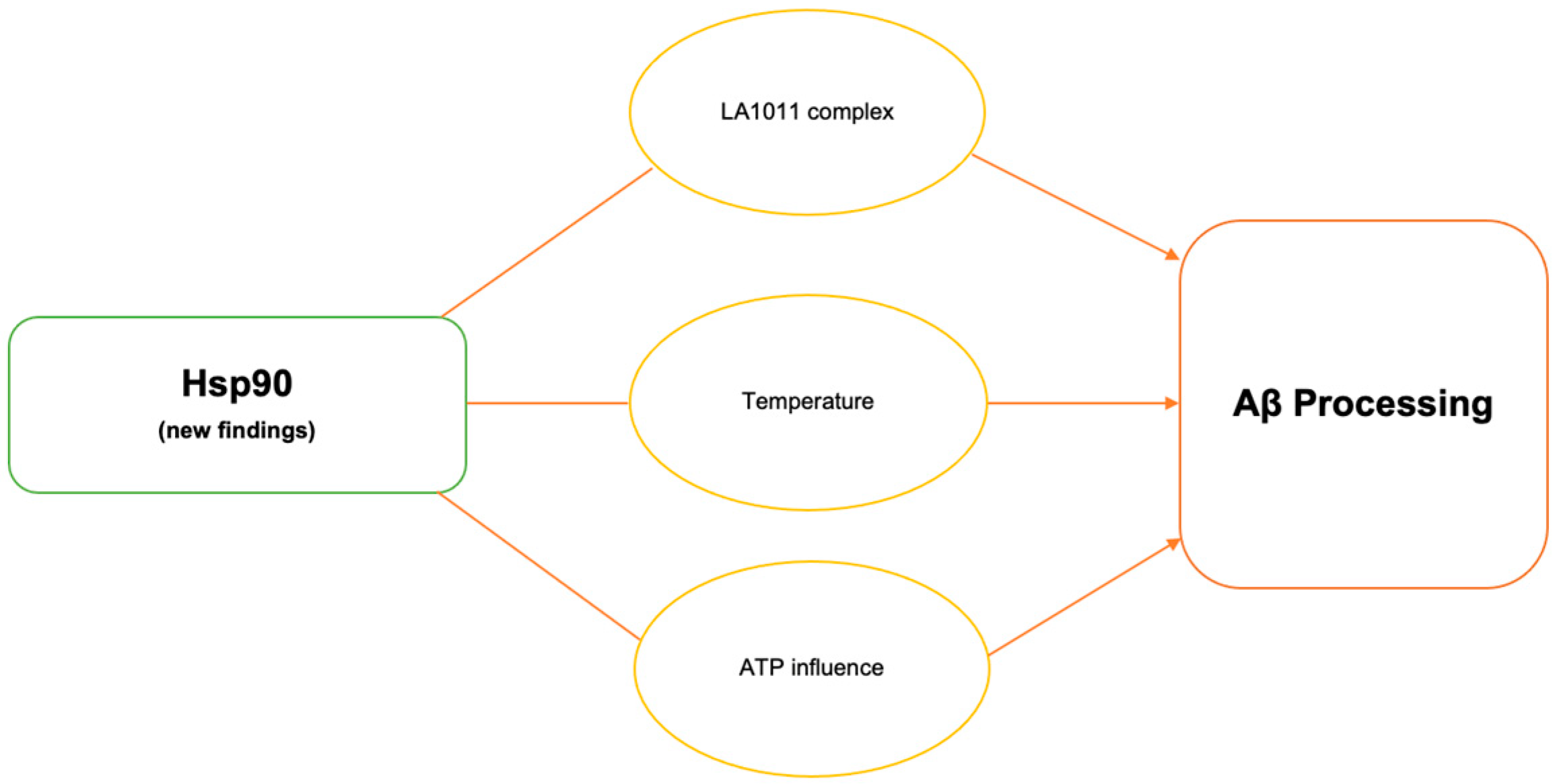

Hsp90 is capable of both solubilizing and suppressing protein aggregates and is also the most prevalent chaperone in mechanistic pathways. Several reports suggested that Hsp90-targeting compounds represent great potential for the development of AD therapy. Recently, Hsp co-inducer 1,4-dihydropyridine derivative LA1011 was shown to have a neuroprotective effect [17]. One of these major discoveries lies in LA1011 complex formation and explores how its structure works with various co-chaperones of Hsp90: FKBP51, FKBP52, PP5, and CHIP [19][25]. By forming complexes with Hsp90, FKBP51 can influence the responsiveness of these receptors to steroid hormones, which are pivotal in regulating immune responses, inflammation, and cellular stress [37][26]. FKBP51 modulates the conformation and activity of specific client proteins like the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and regulates various kinase cascades including insulin signaling [37][26]. Comorbidities like diabetes are recognized to exacerbate Aβ plaques in the context of age-related disorders. Inhibiting insulin binding impairs the brain’s synaptic plasticity, neuroinflammation, and the brain’s ability to metabolize glucose. A decrease in synaptic plasticity in AD individuals is one of the more noticeable ailments since it represents cognitive decline. Also, as a result of a decrease in synaptic plasticity, neuroinflammation activates and promotes tau accumulation [38][27]. Increased levels of FKBP51 in conjunction with age and stress are seen to rise in individuals with AD [19][25]. In transgenic mice models, LA1011 was shown to disturb the binding of FKBP51 to allow for Hsp90 to reduce disease-causing agents [19][25]. The results of the study indicate that there is competition for binding to the hydrophobic pocket at the C-terminal end of Hsp90 between the helical extension of FKBP51’s TPR domain and LA1011 [19][25] Figure 1. The dihydropyridine LA1011 complex was also shown to decrease tau protein aggregation and Aβ plaque aggregation possibly via Hsp90 interactions in AD mice [17,19][17][25].2.2. Temperature on Hsp90 Activity

Extremely high temperatures can induce cellular stress, which in turn can affect the expression and activity of HSP90 and other heat shock proteins. These proteins help cells cope with stress by preventing protein damage and aggregation. Observations revealed that sleep deprivation led to a rise in core body temperature, suggesting a connection between sleep deprivation and Aβ production in AD [39][28]. Inflammatory environments in individuals with AD create a domino effect in the Hsps’ response to antagonistic environments; inflammation downregulates Hsp production since the cell is incapable of managing the stress, increasing Aβ aggregates [38][27]. In disease conditions, Hsp90 has been shown to play a key role in aggregated protein processing and homeostasis. Slight changes in temperature from 37 °C to 39 °C led to enhanced Aβ40 and Aβ42 production in cell culture experiments [39][28]. Hsp90 knockdown experiments at higher temperatures showed increased γ-secretase complex formation and the abolishment of increased Aβ production. Mouse model studies conducted at standard and higher temperatures showed that higher temperatures resulted in increased Hsp90, PS1-CTF, NCT, and γ-secretase complex levels.2.3. Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP)-Mediated Changes in Hsp90 Activity

Neurons’ proper function relies on the efficient production of energy by the mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to reduced ATP generation, impairing neuronal activity and contributing to the cognitive decline observed in AD. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant contributor to the pathogenesis of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, producing higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and NO, leading to oxidative stress [40,41][29][30]. Elevated ROS levels can cause damage to mitochondrial components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, expediting impaired mitochondrial function. This damage can disrupt the electron transport chain, reduce ATP production, and compromise mitochondrial integrity, contributing to a vicious cycle of increasing ROS production and worsening mitochondrial dysfunction. Enhancing mitochondrial health could alleviate several aspects of AD progression and provide a multidimensional strategy to address the complex nature of the disease [42,43,44][31][32][33]. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery is an ATP-dependent process. Essentially, ATP prevents Hsp90 chaperones from performing their inhibitory mechanisms, indicating that chaperones can be manipulated [45,46][34][35]. Hsp90 undergoes conformational changes as it interacts with client proteins. These changes are fundamental for the proper folding and stabilization of client proteins [47,48][36][37]. ATP hydrolysis provides the energy needed to facilitate these conformational changes. According to a recent study, ATP reduces Hsp90′s inhibitory impact on Aβ40 fibrillation by decreasing the hydrophobic surface of Hsp90 [45][34]. When Hsp90 proteins are present, there is no indication of secondary β-sheet structure conformation, and the signal associated with the initial secondary Aβ40 random coil structure gradually diminishes over time, ultimately disappearing as incubation continues possibly due to Hsp90 and Aβ40 large aggregates forming (Figure 1) [45][34]. These findings suggest that Hsp90′s presence keeps Aβ mostly in a monomeric form. Further studies are needed to confirm the effect Hsp90 and ATP have on Aβ fibrillization in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

3. BRICHOS Chaperone Domain

3.1. BRICHOS Interactions

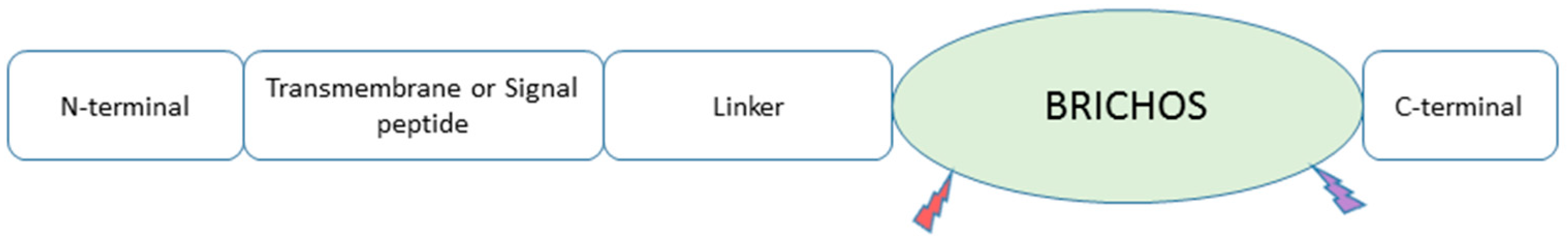

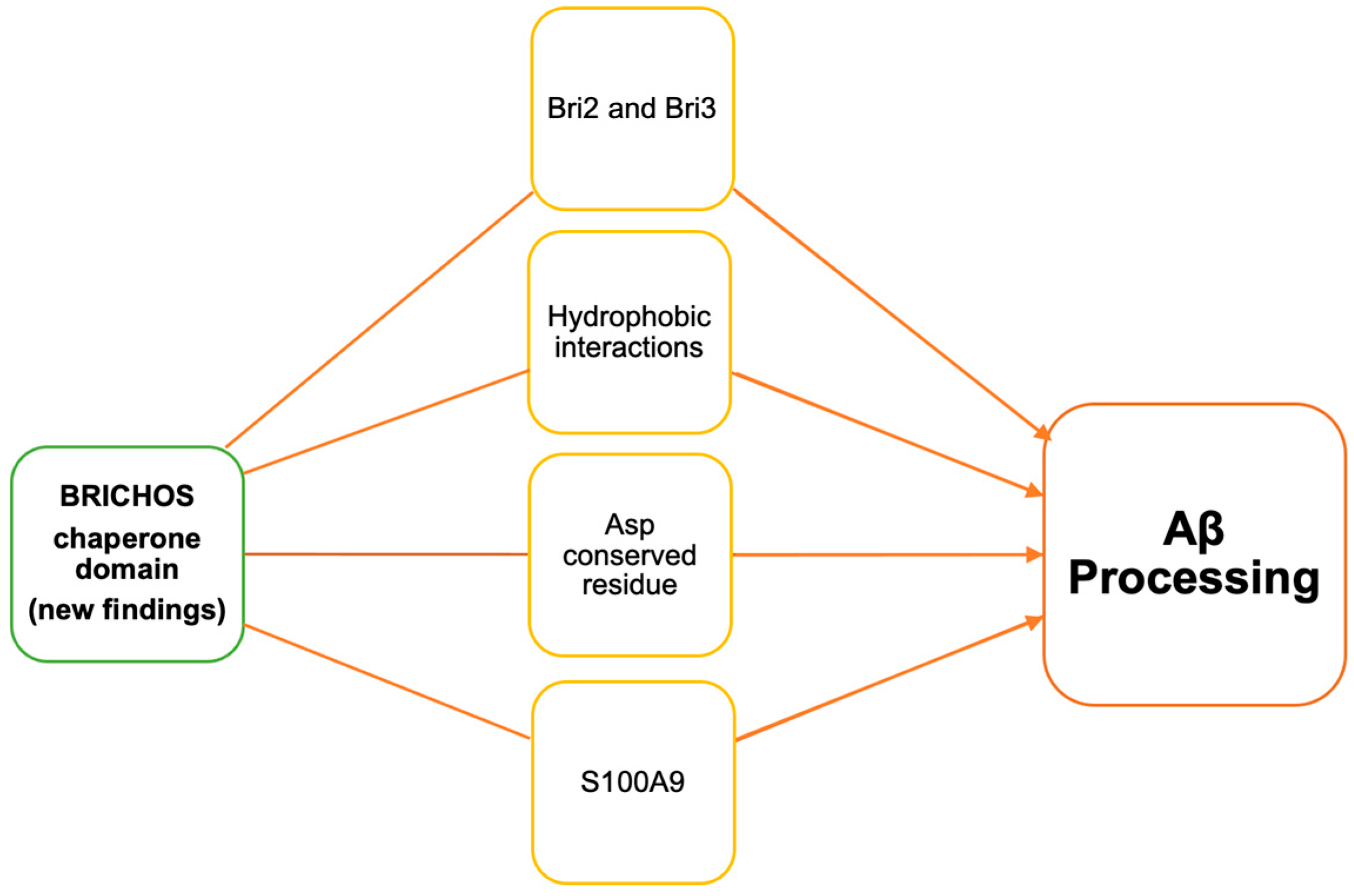

A chaperone that is due for major discussion is the BRICHOS chaperone domain. As shown in Figure 2, all BRICHOS-containing proteins have an N-terminal cytosolic segment, a hydrophobic transmembrane or a signal peptide region, a linker segment, and the BRICHOS domain. The C-terminal segment is present in all BRICHOS except proSP-C [21][20]. Recent studies have shown this chaperone’s involvement in Aβ processing in various ways (Figure 3). Österlund et al. (2022) used the structure prediction algorithm AlphaFold2 and mass spectrometry (MS) to define the BRICHOS domain’s interaction with Aβ. They used the BRICHOS-domain containing proform of lung surfactant protein C (proSP-C) for X-ray crystallography [49][38]. This proSP-C protein is reported to inhibit AB fibrilization [50][39]. Furthermore, Shimozawa et al. showed that BRICHOS interacts with multiple proteins [51][40]. They used mice brain slice cultures incubated with recombinant BRICHOS Bri2 to perform proteomic analysis. They detected the binding of the Spectrin alpha chain, Spectrin beta chain, Myosin-10, unconventional Myosin-Va, Drebrin, Tubulin beta-2A chain, and Actin cytoplasmic 1 to BRICHOS Bri2.

3.2. S100A9 and Bri2 BRICHOS

Another recent study by Manchanda et al. (2023) generated a mutant form of recombinant human Bri2 BRICHOS R221E and tested it in AD animal models [52][41]. Their findings suggest that the mutant form is more efficient than the wild-type form in preventing Aβ42-mediated toxicity in mouse slice culture. Furthermore, using the mouse model, they also showed that the mutated recombinant form is BBB-permeable. They also performed behavioral testing after treating an AD mouse model with the mutated Bri2 BRICHOS when AD pathology began to be observable through symptoms. The behavioral testing data showed that mutated Bri2 BRICHOS helped in boosting recognition and working memory, as was observed through an object recognition test. It is important to note that these positive results were only seen if the treatment started as soon as AD pathology began because this treatment did not show any improved symptoms if it was delayed by 4 months. To confirm these results, the amount of mutated Bri2 BRICHOS found in the brain correlated with the improvement and regaining of recognition and memory [52][41]. Andrade-Talavera et al. investigated the effect of human recombinant Bri2 BRICHOS on S100A9 amyloid kinetics [53][42]. S100A9 was reported to contribute to amyloid processing and neuroinflammation in AD, Parkinson’s disease, and traumatic brain injury. It forms an intracellular amyloid oligomer and Aβ co-aggregates in AD [54,55,56][43][44][45]. S100A9 is an amyloidogenic polypeptide that is inhibited by recombinant Bri2 BRICHOS. The BRICHOS chaperone is seen to cap amyloid fibrils, which not only reduces aggregation but also decreases the inflammatory response (Figure 3) [53][42].3.3. BRICHOS Domain Dependent on Conserved Asp Residue

While all of these recent developments are noteworthy and important, Chen et al.’s data on the conserved aspartate (D) residue in the BRICHOS domain provides further evidence of the potential of this chaperone [57][46]. This particular residue has been consistent across most BRICHOS domain-containing proteins. A few BRICHOS domain-containing proteins have an aspartate to asparagine (N) mutation. Human Bri2 BRICHOS D148N mutation promotes dimerization without affecting function. Their findings suggest that the conserved aspartate residue’s pKa value ranges from pH 6.0 to 7.0, and due to its ionized state, aspartate promotes the domain’s structural flexibility (Figure 3) [57][46]. This chaperone’s role in the context of Hsp90 in Aβ processing is yet to be defined. Hence, future studies will help understand the role of the Bri2 BRICHOS chaperone in AD and its therapeutic potential.3.4. Bri3 BRICHOS Domain Chaperone’s Efficiency

Poska et al. compared the efficiency of BRICHOS Bri2 and Bri3 against Aβ fibrillar and non-fibrillar aggregation [23][22]. Bri2 and Bri3 BRICHOS domains have approximately 60% identical sequences, which indicates similarities in their structure and functions. Bri2 and Bri3 involvement in Aβ has been previously reported [58,59][47][48]. A recent report from Poska et al. suggests that Bri2 and Bri3 BRICHOS have differences in regulating Aβ. Bri2 was found to be more potent against Aβ fibrillar aggregation whereas Bri3 was more potent against non-fibrillar aggregation (Figure 3). Bri3 is only expressed in the CNS whereas Bri2 is expressed in the CNS as well as peripheral tissues [60,61][49][50]. Overall, Bri2 and Bri3 have different tissue distributions and capacities as molecular chaperones. Future studies using mutants and AD models will help in fully understanding their involvement in AD pathogenesis.References

- Wilson, D.M.; Cookson, M.R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 693–714.

- Stelzmann, R.A.; Norman Schnitzlein, H.; Reed Murtagh, F. An english translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “über eine eigenartige erkankung der hirnrinde”. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 429–431.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Facts and Figures. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimer_s_dementia (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Gupta, A.; Goyal, R. Amyloid beta plaque: A culprit for neurodegeneration. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2016, 116, 445–450.

- Nelson, R.; Sawaya, M.R.; Balbirnie, M.; Madsen, A.Ø.; Riekel, C.; Grothe, R.; Eisenberg, D. Structure of the cross-β spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 2005, 435, 773–778.

- Hazenberg, B.P.C. Amyloidosis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 39, 323–345.

- Chen, G.-F.; Xu, T.-H.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.-R.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Amyloid beta: Structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1205–1235.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: Challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 248.

- Wentink, A.; Nussbaum-Krammer, C.; Bukau, B. Modulation of Amyloid States by Molecular Chaperones. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a033969.

- Bukau, B.; Weissman, J.; Horwich, A. Molecular Chaperones and Protein Quality Control. Cell 2006, 125, 443–451.

- Kampinga, H.H.; Craig, E.A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 579–592.

- Li, Z.; Srivastava, P. Heat-shock proteins. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2004, 58, A-1T.

- Fink, A.L. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 425–449.

- Malik, J.A.; Lone, R. Heat shock proteins with an emphasis on HSP 60. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6959–6969.

- Yoo, B.C.; Kim, S.H.; Cairns, N.; Fountoulakis, M.; Lubec, G. Deranged Expression of Molecular Chaperones in Brains of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 280, 249–258.

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Li, J.J.; Xue, Y.; Sakata, K.; Zhu, L.-Q.; Heldt, S.A.; Xu, H.; Liao, F.-F. Hsp90 Chaperone Inhibitor 17-AAG Attenuates Aβ-Induced Synaptic Toxicity and Memory Impairment. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 2464–2470.

- Kasza, Á.; Hunya, Á.; Frank, Z.; Fülöp, F.; Török, Z.; Balogh, G.; Sántha, M.; Bálind, Á.; Bernáth, S.; Blundell, K.L.; et al. Dihydropyridine Derivatives Modulate Heat Shock Responses and have a Neuroprotective Effect in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 53, 557–571.

- Roe, M.S.; Wahab, B.; Török, Z.; Horváth, I.; Vigh, L.; Prodromou, C. Dihydropyridines Allosterically Modulate Hsp90 Providing a Novel Mechanism for Heat Shock Protein Co-induction and Neuroprotection. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 51.

- Sánchez-Pulido, L.; Devos, D.; Valencia, A. BRICHOS: A conserved domain in proteins associated with dementia, respiratory distress and cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 329–332.

- Buxbaum, J.N.; Johansson, J. Transthyretin and BRICHOS: The Paradox of Amyloidogenic Proteins with Anti-Amyloidogenic Activity for Aβ in the Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 119.

- Willander, H.; Hermansson, E.; Johansson, J.; Presto, J. BRICHOS domain associated with lung fibrosis, dementia and cancer—A chaperone that prevents amyloid fibril formation? FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3893–3904.

- Poska, H.; Leppert, A.; Tigro, H.; Zhong, X.; Kaldmäe, M.; Nilsson, H.E.; Hebert, H.; Chen, G.; Johansson, J. Recombinant Bri3 BRICHOS domain is a molecular chaperone with effect against amyloid formation and non-fibrillar protein aggregation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9817.

- Leppert, A.; Poska, H.; Landreh, M.; Abelein, A.; Chen, G.; Johansson, J. A new kid in the folding funnel: Molecular chaperone activities of the BRICHOS domain. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4645.

- Nishimura, T.; Akiyoshi, K. Artificial Molecular Chaperone Systems for Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Synthetic Molecules. Bioconj. Chem. 2020, 31, 1259–1267.

- Roe, S.M.; Török, Z.; McGown, A.; Horváth, I.; Spencer, J.; Pázmány, T.; Vigh, L.; Prodromou, C. The Crystal Structure of the Hsp90-LA1011 Complex and the Mechanism by Which LA1011 May Improve the Prognosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1051.

- Smedlund, K.B.; Sanchez, E.R.; Hinds, T.D., Jr. FKBP51 and the molecular chaperoning of metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 862–874.

- Rowles, J.E.; Keane, K.N.; Gomes Heck, T.; Cruzat, V.; Verdile, G.; Newsholme, P. Are Heat Shock Proteins an Important Link between Type 2 Diabetes and Alzheimer Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8204.

- Noorani, A.A.; Yamashita, H.; Gao, Y.; Islam, S.; Sun, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Enomoto, H.; Zou, K.; Michikawa, M. High temperature promotes amyloid β-protein production and γ-secretase complex formation via Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 18010–18022.

- Priyanka; Seth, P. Insights into the Role of Mortalin in Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and HIV-1-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 903031.

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Belinchón-deMiguel, P.; Martinez-Guardado, I.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Mitochondria and Brain Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2488.

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583.

- Hoye, A.T.; Davoren, J.E.; Wipf, P.; Fink, M.P.; Kagan, V.E. Targeting mitochondria. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 87–97.

- Picone, P.; Nuzzo, D.; Giacomazza, D.; Di Carlo, M. β-Amyloid Peptide: The Cell Compartment Multi-faceted Interaction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 37, 250–263.

- Wang, H.; Lallemang, M.; Hermann, B.; Wallin, C.; Loch, R.; Blanc, A.; Balzer, B.N.; Hugel, T.; Luo, J. ATP Impedes the Inhibitory Effect of Hsp90 on Aβ(40) Fibrillation. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166717.

- Ali, M.M.U.; Roe, S.M.; Vaughan, C.K.; Meyer, P.; Panaretou, B.; Piper, P.W.; Prodromou, C.; Pearl, L.H. Crystal structure of an Hsp90–nucleotide–p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nature 2006, 440, 1013–1017.

- Picard, D. Heat-shock protein 90, a chaperone for folding and regulation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1640–1648.

- McClellan, A.J.; Xia, Y.; Deutschbauer, A.M.; Davis, R.W.; Gerstein, M.; Frydman, J. Diverse Cellular Functions of the Hsp90 Molecular Chaperone Uncovered Using Systems Approaches. Cell 2007, 131, 121–135.

- Österlund, N.; Vosselman, T.; Leppert, A.; Gräslund, A.; Jörnvall, H.; Ilag, L.L.; Marklund, E.G.; Elofsson, A.; Johansson, J.; Sahin, C.; et al. Mass Spectrometry and Machine Learning Reveal Determinants of Client Recognition by Antiamyloid Chaperones. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2022, 21, 100413.

- Knight, S.D.; Presto, J.; Linse, S.; Johansson, J. The BRICHOS Domain, Amyloid Fibril Formation, and Their Relationship. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 7523–7531.

- Shimozawa, M.; Tigro, H.; Biverstål, H.; Shevchenko, G.; Bergquist, J.; Moaddel, R.; Johansson, J.; Nilsson, P. Identification of cytoskeletal proteins as binding partners of Bri2 BRICHOS domain. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 125, 103843.

- Manchanda, S.; Galan-Acosta, L.; Abelein, A.; Tambaro, S.; Chen, G.; Nilsson, P.; Johansson, J. Intravenous treatment with a molecular chaperone designed against β-amyloid toxicity improves Alzheimer’s disease pathology in mouse models. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 487–502.

- Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Chen, G.; Pansieri, J.; Arroyo-García, L.E.; Toleikis, Z.; Smirnovas, V.; Johansson, J.; Morozova-Roche, L.; Fisahn, A. S100A9 amyloid growth and S100A9 fibril-induced impairment of gamma oscillations in area CA3 of mouse hippocampus ex vivo is prevented by Bri2 BRICHOS. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 219, 102366.

- Wang, C.; Iashchishyn, I.A.; Pansieri, J.; Nyström, S.; Klementieva, O.; Kara, J.; Horvath, I.; Moskalenko, R.; Rofougaran, R.; Gouras, G.; et al. S100A9-Driven Amyloid-Neuroinflammatory Cascade in Traumatic Brain Injury as a Precursor State for Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12836.

- Wang, C.; Klechikov, A.G.; Gharibyan, A.L.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Jarvet, J.; Zhao, L.; Jia, X.; Shankar, S.K.; Olofsson, A.; Brännström, T.; et al. The role of pro-inflammatory S100A9 in Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-neuroinflammatory cascade. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 127, 507–522.

- Horvath, I.; Iashchishyn, I.A.; Moskalenko, R.A.; Wang, C.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Wallin, C.; Gräslund, A.; Kovacs, G.G.; Morozova-Roche, L.A. Co-aggregation of pro-inflammatory S100A9 with α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: Ex vivo and in vitro studies. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 172.

- Chen, G.; Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Zhong, X.; Hassan, S.; Biverstål, H.; Poska, H.; Abelein, A.; Leppert, A.; Kronqvist, N.; Rising, A.; et al. Abilities of the BRICHOS domain to prevent neurotoxicity and fibril formation are dependent on a highly conserved Asp residue. RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3, 1342–1358.

- Matsuda, S.; Matsuda, Y.; D’Adamio, L. BRI3 inhibits amyloid precursor protein processing in a mechanistically distinct manner from its homologue dementia gene BRI2. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 15815–15825.

- Matsuda, S.; Matsuda, Y.; Snapp, E.L.; D’Adamio, L. Maturation of BRI2 generates a specific inhibitor that reduces APP processing at the plasma membrane and in endocytic vesicles. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 1400–1408.

- Martin, L.; Fluhrer, R.; Haass, C. Substrate requirements for SPPL2b-dependent regulated intramembrane proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 5662–5670.

- Dolfe, L.; Tambaro, S.; Tigro, H.; Del Campo, M.; Hoozemans, J.J.M.; Wiehager, B.; Graff, C.; Winblad, B.; Ankarcrona, M.; Kaldmäe, M.; et al. The Bri2 and Bri3 BRICHOS Domains Interact Differently with Aβ(42) and Alzheimer Amyloid Plaques. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2018, 2, 27–39.