Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Tiago Gonçalves.

Sustainable careers are regarded as a complex mental schema represented by experiences and continuity patterns grounded on individual subjective evaluations, such as happiness, health and productivity.

- sustainable careers

- well-being

- job satisfaction

- organizational citizenship behavior

1. Introduction

Sustainable careers are regarded as a cyclical process characterized by mutually beneficial consequences for both the individual and the environment from a long-term perspective [1]. Therefore, sustainable careers can be defined as a form of human sustainability aligned with the ability of individuals to create, test and maintain their adaptive capacity [2]. Sustainable careers have similarities with physical sustainability when considering the consequences that organizational activity can have on material and physical resources [3]. Likewise, sustainable careers also present similarities with social sustainability when considering the impact that organizational activities can have on a material and physical level and the psychological impact on an employee [3,4][3][4]. Therefore, career adaptability is a psychosocial construct [5]. Kuchinke [6] emphasizes the importance and development of human beings when addressing the issue of the sustainability of human resources. Nevertheless, although sustainable careers discuss the psychosocial role of career adaptability as one of the core dimensions that shape the person-centered approach to sustainable careers [1], career adaptability by itself is not sufficient to describe career sustainability. Workers who present higher levels of adaptability are prone to be better prepared for future career challenges [7]. According to De Vos and colleagues [1], however, only the combination of adaptivity and adaption with career competencies can promote career sustainability at the personnel level, making career adaptation a subdimension of the “Person” dimension defended by the authors.

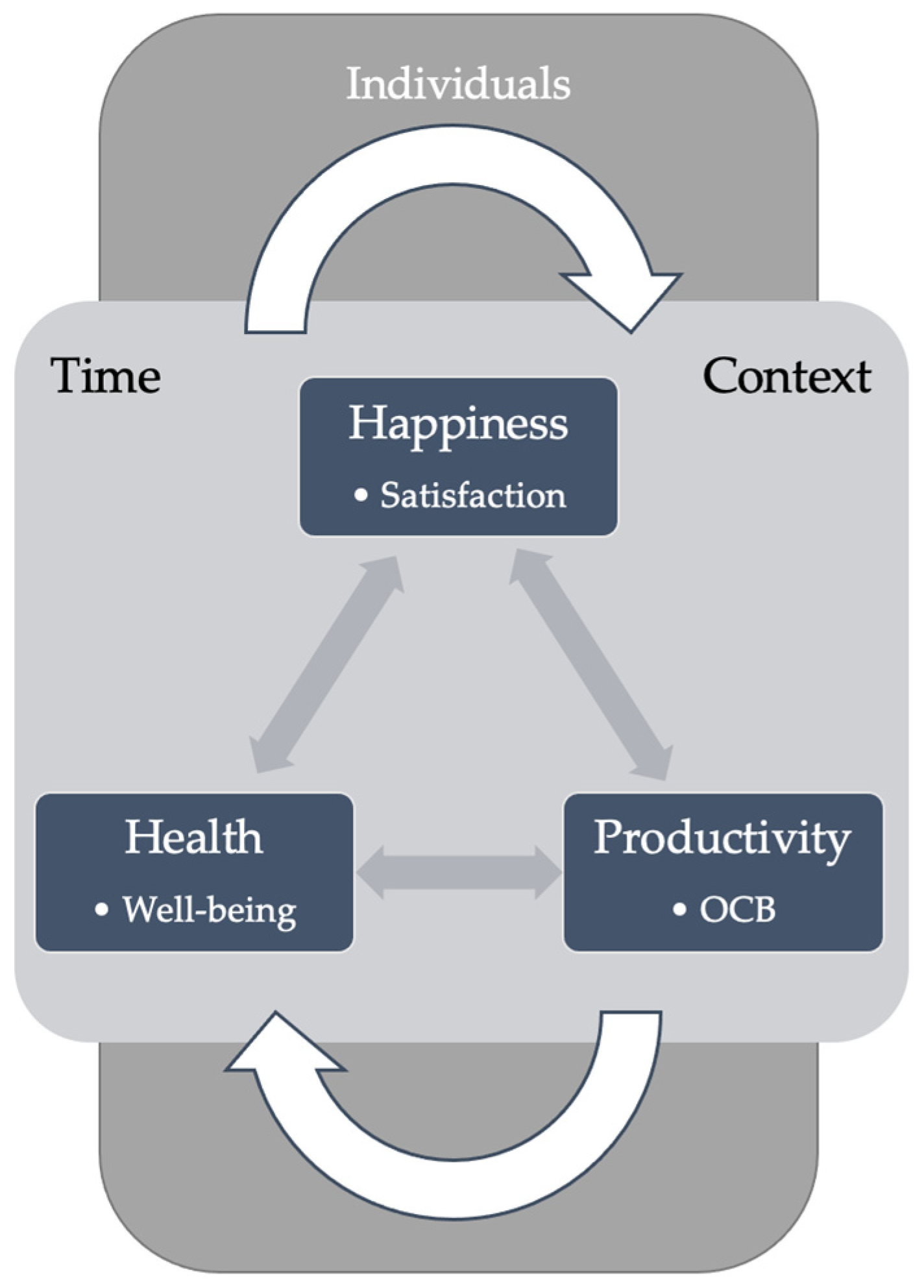

The literature related to careers has paid special attention to the analysis and study of the topic of sustainable careers [8,9][8][9]. Considering such scarcity, the present work is based on the conceptual sustainable career model as proposed by De Vos and colleagues [1]. The authors argue that, at the individual level, sustainable careers are defined by three key indicators: Happiness, Health and Productivity [10]. Happiness refers to the adjustment between goals, values and career that align with the employee’s personal growth [10]. Health refers to career adjustment and is related to the employee’s physical and psychological mental capacities and their perception of quality of life [11,12][11][12]. Productivity refers to the employee’s performance and respective long-term career progression within the organization [13].

However, despite the growing research on the topic [1[1][14],14], Müller and colleagues [12] explore the main theoretical studies on sustainability and careers [15[15][16],16], identifying a gap in the literature that invites empirical investigation on the subject. The validation of a sustainable career variable lacks conceptual clarification with no accepted indicators for measuring the concept; thus, it remains in an embryonic state [17]. There is much that still needs to be undertaken regarding the operationalization of sustainable careers [18]. Additionally, some recent tentative efforts to develop frameworks for sustainable careers originated propositions for particular audiences, such as vocational students [19]. Similarly, wthe researchers find attempts to develop and empirically test a sustainable career scale that ends up exploring context-dependent variables on specific workplace samples of mature employees [20]. At present, there seems to be no record of an empirical test of De Vos and colleagues’ [1] proposed model using widely accepted measures that are neither context specific nor designed for particular users [18].

2. Sustainable Careers

According to Van der Heijden et al. [20], sustainable careers are reflected through a variety of experiences involving a diversity of patterns, representing different social spaces and having different meanings for each individual that cross different social spaces and provide meaning to each individual. Despite the variety of experiences lived by every person, a career can be designated as sustainable when it meets similar criteria to that of physical sustainability (represented by the consequences of the organizational activity carried out on each employee) and social sustainability (represented by the consequences of the organizational activity carried out on the physical and psychological health of each employee) [3,4,20][3][4][20]. Therefore, career sustainability is built on the ability of human beings to create, test and maintain their adaptive capacity [2], revealing the contribution of psychological resources to sustainable careers [17]. De Vos and colleagues [1] developed an integrative theoretical assumption that focuses on the individual, their organizational context and their actions over time [21]. This view proposes a systemic approach to understanding the influence of the social context (colleagues, organization and other aspects beyond the employee’s personal life) on building a sustainable career [22]. Additionally, this line of research assumes a dynamic approach to careers as cycles of individual decisions [20[20][22],22], which are context dependent as time goes by [23]. The time factor comprises the long-term interaction of individuals with society [21], involving changes in the workplace that consequently impact their careers [15]. The sustainable careers model (Figure 1) considers three dimensions: Person, Context and Time [1]. Sustainable careers reflect beneficial consequences for the person and their context from a long-term perspective. The three indicators portray three key characteristics of a sustainable career (Happiness, Health and Productivity), which altogether produce positive results reflected in career success [1,24][1][24]. These indicators reflect that which is intrinsic to individual social prosperity and well-being [20]. Happiness refers to the adjustment between individual goals, values and/or needs combined with personal growth and/or issues related to the balance between work and personal life [11]. Health refers to the adjustment between the physical and mental capabilities of the employee related to the perception of well-being and quality of life of each individual [12]. Finally, productivity refers to the employee’s organizational performance combined with long-term career progression [13]. According to De Vos and colleagues [1], the integration of the three indicators operates on an idea of fit, recognizing its relevancy for both individuals and organizations.3. Well-Being

The concept of psychological well-being has gained special attention in organizations [26][25]. Research on well-being at work is found in the literature supported by two perspectives [27,28,29][26][27][28]—hedonic and eudaemonic [30][29]. The first focuses on the conceptualization of well-being as a cognitive and affective assessment that an individual makes of his or her life in an integrated way [26,29][25][28]. The second, while less studied [27,28][26][27], defends an approach to the phenomenon from an integrated perspective of alignment with beliefs and values based on mental states that are congruent and authentic with the idea of the self [27][26]. However, the difficult operationalization of the second perspective [27,28][26][27] indicates a strong tendency to understand well-being in the organizational context following a hedonic perspective [27][26]. Ryan and Deci [30][29] discuss in detail the dichotomy of perspectives that are aligned with the concept of well-being, suggesting possible theoretical solutions that support the operationalization of this concept in the context of the life cycles of individuals in organizations. The choice of well-being as a Health proxy reflects both a significant rise in the literature surrounding psychological health in the workplace context [31][30] and the parallel growth of research on its physical consequences. As stated by the World Health Organization, well-being reflects “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [32][31] In the organizational context, similar parallels are discussed pertaining to the consequences of well-being on job satisfaction and performance [33][32], constituting a core health-related concern in HR management practices. The Self-Determination Theory [34][33] states that a proactive employee stimulates development and growth and interacts with the surrounding social world when dedicated to satisfying three basic ideas: competence (which comprises success and how each person achieves the expected result), relationship (mutual respect) and autonomy (employee initiative) [26,34,35][25][33][34]. Ryan and Deci [30][29] argue that the satisfaction of these three needs is essential for well-being and psychological growth. The Person–Environment Fit Theory argues that employee performance and well-being levels are higher where there is a suitable profile for the proposed role. Notwithstanding, the lack of alignment between employee preferences and role characteristics will be detrimental to their respective well-being [36][35]. This way, the profiles that do not best match the jobs will take longer to perform the associated functions, jeopardizing employee well-being [37][36]. Individual well-being favors both organizations through increased motivation, productivity, and reduced absenteeism, as well as society, given that people’s psychological health results in global satisfaction [38,39][37][38]. Ryff et al. [40][39] report that workers with higher levels of well-being tend to be more productive and have better physical and psychological health when compared to workers with low levels of well-being. Expanding on such a view, Wright and Cropanzano [41][40] in their seminal work on the happy–productive hypothesis, discuss the importance of the combined effects of well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Recent literature addresses this relationship, referring to the combined influence of both well-being and job satisfaction as predicting stressors of positive emotions [42][41], and gaining traction during the COVID-19 pandemic as a combination of measures to understand the needs of organizational support [43][42].4. Job Satisfaction

Happiness stems from “job satisfaction” [46][43]. Happiness is a daily objective of human beings, as they seek to extend it to all domains of their lives. Consequently, Happiness measures the degree of satisfaction that an individual has with their own life [47][44]. Satisfaction in an organizational context is a positive emotional state that exists in the performance of an employee’s daily functions [48,49][45][46]. In addition to an emotional state, job satisfaction is an attitude that translates into employee behavior [50][47]. Job satisfaction can be addressed from two perspectives: the humanitarian perspective and the utilitarian perspective [51][48]. The humanitarian perspective states that the level of satisfaction is measured according to how employees are valued in the organization [51][48]. The utilitarian perspective, on the other hand, considers that employee satisfaction can trigger attitudes from employees that influence the functioning of the organization [51][48]. The Need Theory by McClelland [52][49] explains how the individual need for achievement, affiliation, and power influence employees’ actions within an organizational context. It states that an organization’s employees, whose primary needs are satisfied through workplace experiences, will obtain higher satisfaction in the roles they perform [53][50]. Although such a theoretical framework exposes the importance of satisfaction for organizations [54][51] and individuals [55][52], the measurement of the construct in the literature is built on subjective judgments of adequacy, sufficiency and acceptance [28,29][27][28]. The reflection of these psychological needs as dimensions of satisfaction can thus be translated into judgments of working conditions, conditions of the reward models existing in the organization, and even the conditions of access and career development [28,56][27][53]. Likewise, empirical evidence also suggests the existence of positive states of mind when the conditions attached to satisfaction in the workplace are fulfilled, providing potential for discussion on the possible relationship between satisfaction and happiness [44,55][52][54]. However, the concern of organizations to provide working conditions to meet the satisfaction needs of their employees presents a robust line of investigation focused on the behavioral consequences of job satisfaction [44,45][54][55]. For example, Chiaburu and colleagues [45][55], in a meta-analysis that sought to explore predictors of OCB in the literature, observed satisfaction as a key predictor effect for OCB—considering either the direction of individual (with other colleagues) or organizational behavior.5. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is defined by Organ [57][56] as voluntary cooperative behaviors that workers exercise toward their colleagues that go beyond their functions [58,59][57][58]. This behavior leads to greater job satisfaction and a greater sense of perceived fairness [60][59]). In presenting this argument, Organ [61,62][60][61] suggests that OCB represents an input to the employee equity ratio that can be changed more easily than other inputs that involve the daily tasks of employees [63][62]. OCB is a predictive source of performance in organizations. Supported by the Psychological Impact Theory, which addresses the effects of human resources management (HRM) practices on attitudes that influence organizational performance [64[63][64],65], OCB reflects not only the innate characteristics of the task or work that are predictive of performance but also behaviors that portray extra job tasks [65,66][64][65]. HR managers can make use of progressive HRM practices [67][66] to stimulate employees to perform their work beyond in-role behaviors: extra task behaviors. Following a conceptual discussion on the possible effects of OCB on organizations [66][65], its particular importance is observed in promoting cooperation and coordination between the different levels of the organization and in guaranteeing a capacity for stability and adaptation to change. Such aspects are corroborated by further research [64,65,68][63][64][67]. According to Organ [62][61], OCB translates into feelings of belonging, commitment, and loyalty to the organization in the long term, which are highly important predictors for achieving productivity in high-performance organizational systems [69][68]. Several authors have followed the work of Smith, Organ and Near [70][69] and further refined the concept of OCB (e.g., the view of Ocampo et al. [71][70]). This line of research has been explored in different contexts and perspectives, showing that OCB is related both at an individual (IOCB) and organizational (OOCB) level and that perspectives should be distinguished [71,72][70][71]. Inspired by the five dimensions presented by Bateman & Organ [73][72]: altruism, courtesy, conscience, civic virtue and sportsmanship, Williams & Anderson [74][73] address OCB in two groups: altruism and courtesy comprise the IOCB and civic virtue. Conscience and sportsmanship comprise the organizational perspective (OOCB) [71,75][70][74]. Sustainable careers comprise a resource preservation process based on Hobfoll’s Theory of Resource Conservation [76][75], arguing that employees try their best to protect and acquire new resources [77][76]. However, when there is a loss of resources, they choose to reduce their behavior and conserve the most valuable resources because such an option is supposed to preserve the sustainability of a career [1]. OCB is an extra-task voluntary behavior for the benefit of the organization and/or colleagues that leads to the delivery of emotional and cognitive resources by employees [63,78][62][77]. Expanding on such a rationale, evidence also suggests that the perception of OCB activities, considering both individual and organizational-oriented OCBs, are related to well-being-related dimensions [79][78]. Through the lens of both engagement and positive affective commitment, engagement in OCBs can promote citizenship-oriented initiatives as per the job role [79,80][78][79]. By extension, evidence also suggests that the overreliance on motivation-oriented approaches by HRM practices stemming from demands–resources models can further cherish OCB behaviors, being mediated by feelings of well-being [81][80].6. The Integrated Nature of Sustainable Careers Indicators

For De Vos and colleagues [1], the integration of happiness, health and productivity in a taxonomy of sustainability in careers operates according to the idea of fit. The three indicators are of recognized importance for individuals and organizations. The perspective of adjusting the three indicators of sustainable careers is aligned with the central premises of human sustainability [2]. The set of indicators works as a mechanism that responds to the changes that emerge from contextual influences happening in a dynamic and combined way [3]. Research corroborates the assumptions that the three indicators reflect a combined and integral reaction to contextual influences. Tordera and colleagues [25][81] discuss the close relationship between the three indicators of sustainable careers with HRM practices. Likewise, the idea of a combined influence of the three indicators is also corroborated in the career management of self-employed workers [10]. However, the operationalization of sustainability, as proposed by De Vos and colleagues [1], presents problems of an empirical nature, as discussed in the literature [10,11,25][10][11][81]. The difficulties in studying sustainable careers concern measuring the happiness, health and productivity indicators since these are complex phenomena to measure [1,25][1][81]. The challenge is further intensified by the scarcity of existing measures to study sustainable careers [11,25][11][81]. Such evidence provides two arguments about the conceptual reality of sustainable careers: (a) the scarcity of measures to address sustainable careers leads to the need to use proxies; (b) the choice of proxies must obey an integrated association form, presenting significant and observable positive and negative relationship directions in the three indicators. That is, individuals who show high levels of one indicator (let us say the productivity proxy) must also show high levels of the other two indicators (in the same example, the health and happiness proxies), thus corroborating the conceptual model [1] and the validity of the choice of measures to estimate the phenomenon. Similarly, individuals who show low levels of one indicator (let us say the productivity proxy) must also show low levels of the other two indicators (in the same example, the health and happiness proxies).References

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable Careers: Towards a Conceptual Model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196.

- Holling, C.S. Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405.

- Pfeffer, J. Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 24, 34–35.

- Garavan, T.N.; McGuire, D. Human Resource Development and Society: Human Resource Development’s Role in Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability, and Ethics in Organizations. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2010, 12, 487–507.

- Johnston, C.S. A Systematic Review of the Career Adaptability Literature and Future Outlook. J. Career Assess. 2016, 26, 3–30.

- Kuchinke, K.P. Human Development as a Central Goal for Human Resource Development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2010, 13, 575–585.

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis of Relationships with Measures of Adaptivity, Adapting Responses, and Adaptation Results. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 17–34.

- Anseel, F. Agile Learning Strategies for Sustainable Careers: A Review and Integrated Model of Feedback-Seeking Behavior and Reflection. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 51–57.

- Veld, M.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Semeijn, J.H. Home-To-Work Spillover and Employability among University Employees. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1280–1296.

- van den Groenendaal, S.M.E.; Akkermans, J.; Fleisher, C.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Poell, R.F.; Freese, C. A Qualitative Exploration of Solo Self-Employed Workers’ Career Sustainability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 134, 103692.

- Chin, T.; Jawahar, I.M.; Li, G. Development and Validation of a Career Sustainability Scale. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 769–787.

- Müller, C.V.; Scheffer, A.B.B. Why Adopt a Sustainability Approach in Career Studies? A Theoretical Essay about the Foundations and the Relevance of the Discussion. Rev. De Adm. De Empres. 2022, 62, 1–19.

- Heijde, C.M.V.D.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.J.M. A Competence-Based and Multidimensional Operationalization and Measurement of Employability. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 449–476.

- Donald, W.E.; Ashleigh, M.J.; Baruch, Y. Students’ Perceptions of Education and Employability. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 513–540.

- Baruch, Y.; Rousseau, D.M. Integrating Psychological Contracts and Ecosystems in Career Studies and Management. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 84–111.

- de Lange, A.H.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. Human Resource Management and Sustainability at Work across the Lifespan: An Integrative Perspective. In Facing the Challenges of a Multi-Age Workforce; Finkelstein, L.M., Truxillo, D.M., Fraccaroli, F., Kanfer, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–30.

- Nimmi, P.M.; Kuriakose, V.; Donald, W.E.; Nowfall, S.M. HERO Elements of Psychological Capital: Fostering Career Sustainability via Resource Caravans. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2021, 30, 199–210.

- Chin, T.; Li, G.; Jiao, H.; Addo, F.; Jawahar, I.M. Career sustainability during manufacturing innovation: A review, a conceptual framework and future research agenda. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 509–528.

- Rizwan, A.; Serbaya, S.H.; Saleem, M.; Alsulami, H.; Karras, D.A.; Alamgir, Z. A Preliminary Analysis of the Perception Gap between Employers and Vocational Students for Career Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11327.

- Van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A. Sustainable Careers: Introductory Chapter. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 1–19.

- Richardson, J.; McKenna, S. An Exploration of Career Sustainability in and after Professional Sport. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 117, 103314.

- Van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A.; Akkermans, J.; Spurk, D.; Semeijn, J.; Van der Velde, M.; Fugate, M. Sustainable Careers across the Lifespan: Moving the Field Forward. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103344.

- Nagy, N.; Froidevaux, A.; Hirschi, A. Lifespann Perspectives on Careers and Career Developmen. In Work across the Lifespan; Baltes, B., Rudolph, C., Zacher, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–43.

- Hall, D.T.; Lee, M.D.; Kossek, E.E.; Heras, M.L. Pursuing Career Success While Sustaining Personal and Family Well-Being: A Study of Reduced-Load Professionals over Time. J. Soc. Issues 2012, 68, 742–766.

- Hoffmann-Burdzińska, K.; Rutkowska, M. Work Life Balance as a Factor Influencing Well-Being. J. Posit. Manag. 2015, 6, 87–101.

- Bartels, A.L.; Peterson, S.J.; Reina, C.S. Understanding Well-Being at Work: Development and Validation of the Eudaimonic Workplace Well-Being Scale. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215957.

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Alegre, J. Happiness at Work: Developing a Shorter Measure. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 27, 1–21.

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Alegre, J. Unselfish Leaders? Understanding the Role of Altruistic Leadership and Organizational Learning on Happiness at Work (HAW). Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 633–649.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166.

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. A Systematic Review of Measures for Psychological Well-Being in Physical Activity Studies and Identification of Critical Issues. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 473–485.

- World Health Organization. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/mental-health (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Peccei, R.; Van De Voorde, K. Human Resource Management–Well-Being–Performance Research Revisited: Past, Present, and Future. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 539–563.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78.

- Gagné, M. Vansteenkiste. Self-Determination Theory’s Contribution to Positive Organizational Psychology. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Bakker, A., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 61–82.

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of Individuals’ Fit at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person-Job, Person-Organisation, Person-Group, and Person-Supervisor Fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342.

- Bartoll, X.; Ramos, R. Working Hour Mismatch, Job Quality, and Mental Well-Being across the EU28: A Multilevel Approach. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 733–745.

- Burke, R. Do Managerial Men Benefit from Organizational Values Supporting Work-Personal Life Balance? Women Manag. Rev. 2000, 15, 81–87.

- Grady, G.; McCarthy, A.; Darcy, C.; Kirrane, M. Work Life Balance: Policies and Initiatives in Irish Organisations: A Best Practice Management Guide; Oak Tree Press: Cork, Ireland, 2008.

- Ryff, C.; Singer, B. From Social Structure to Biology: Integrative Science in Pursuit of Human Health and Well-Being. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Lopez, S., Ed.; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 541–554.

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Psychological Well-Being and Job Satisfaction as Predictors of Job Performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 84–94.

- Dreer, B. Teachers’ Well-Being and Job Satisfaction: The Important Role of Positive Emotions in the Workplace. Educ. Stud. 2021, 1–17.

- Capone, V.; Borrelli, R.; Marino, L.; Schettino, G. Mental Well-Being and Job Satisfaction of Hospital Physicians during COVID-19: Relationships with Efficacy Beliefs, Organizational Support, and Organizational Non-Technical Skills. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3734.

- Buitendach, J.H.; Rothmann, S. The Validation of the Minnesota Job Satisfaction Questionnaire in Selected Organisations in South Africa: Original Research. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 7, 1–8.

- Dhingra, V.; Dhingra, M. Who Doesn’t Want to Be Happy? Measuring the Impact of Factors Influencing Work–Life Balance on Subjective Happiness of Doctors. Ethics Med. Public Health 2021, 16, 100630.

- Locke, E. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfactio. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349.

- Schneider, B.; Snyder, R.A. Some Relationships between Job Satisfaction and Organization Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 318–328.

- Aruldoss, A.; Kowalski, K.B.; Parayitam, S. The Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Work Life Balancemediating Role of Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Commitment: Evidence from India. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2022, 19, 240–271.

- Abdallah, A.; Obeidat, B.; Aqqad, N.; Al Janini, M.N.; Dahiyat, S.E. An Integrated Model of Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Analysis in Jordan’s Banking Sector. Commun. Netw. 2017, 09, 28–53.

- McClelland, D.C. How Motives, Skills, and Values Determine What People Do. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 812–825.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Efraty, D.; Siegel, P.; Lee, D.-J. A New Measure of Quality of Work Life (QWL) Based on Need Satisfaction and Spillover Theories. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 241–302.

- Chiva, R.; Alegre, J. Organizational Learning Capability and Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Assessment in the Ceramic Tile Industry. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 323–340.

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Simone, C.; Fernández-Guerrero, R. The Human Side of Leadership: Inspirational Leadership Effects on Follower Characteristics and Happiness at Work (HAW). J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 162–171.

- Smith, P.C.; Kendall, L.M.; Hulin, C.L. The Measurement of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement: A Strategy for the Study of Attitudes; Rand Mcnally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969.

- Ock, J. How Satisfied Are You with Your Job? Estimating the Reliability of Scores on a Single-Item Job Satisfaction Measure. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2020, 28, 297–309.

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Oh, I.-S.; Stoverink, A.C.; Park, H.; Bradley, C.; Barros-Rivera, B.A. Happy to Help, Happy to Change? A Meta-Analysis of Major Predictors of Affiliative and Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 132, 103664.

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: It’s Construct Clean-up Time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97.

- Cem-Ersoy, N.C.; Derous, E.; Born, M.P.; van der Molen, H.T. Antecedents of Organizational Citizenship Behavior among Turkish White-Collar Employees in The Netherlands and Turkey. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 49, 68–79.

- Zeinabadi, H.; Salehi, K. Role of Procedural Justice, Trust, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment in Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) of Teachers: Proposing a Modified Social Exchange Model. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 1472–1481.

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Recent Trends and Developments. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 295–306.

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books, Cop: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988.

- Organ, D.W. The Motivational Basis of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Cummings, L., Staw, B., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1990.

- Lee, K.; Allen, N.J. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Workplace Deviance: The Role of Affect and Cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 131–142.

- Garg, N. High Performance Work Practices and Organizational Performance-Mediation Analysis of Explanatory Theories. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 797–816.

- Kim, M.; Jang, J. The Impact of Employees’ Perceived Customer Citizenship Behaviors on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: The Mediating Roles of Employee Customer-Orientation Attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 1–26.

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563.

- Delaney, J.T.; Huselid, M.A. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Perceptions of Organizational Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 949–969.

- Gupta, V.; Mittal, S.; Ilavarasan, P.V.; Budhwar, P. Pay-For-Performance, Procedural Justice, OCB and Job Performance: A Sequential Mediation Model. Pers. Rev. 2022; ahead-of-print.

- Pahos, N.; Galanaki, E. Performance Effects of High Performance Work Systems on Committed, Long-Term Employees: A Multilevel Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 825397.

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature and Antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663.

- Ocampo, L.; Acedillo, V.; Bacunador, A.M.; Balo, C.C.; Lagdameo, Y.J.; Tupa, N.S. A Historical Review of the Development of Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) and Its Implications for the Twenty-First Century. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 821–862.

- McNeely, B.L.; Meglino, B.M. The Role of Dispositional and Situational Antecedents in Prosocial Organizational Behavior: An Examination of the Intended Beneficiaries of Prosocial Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 836–844.

- Bateman, T.S.; Organ, D.W. Job Satisfaction and the Good Soldier: The Relationship between Affect and Employee “Citizenship”. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 587–595.

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617.

- Pradhan, R.K.; Jena, L.K.; Kumari, I.G. Effect of Work–Life Balance on Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: Role of Organizational Commitment. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17 (Suppl. S3), 15S–29S.

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524.

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364.

- Lin, Q.; Guan, W.; Zhang, N. Work–Family Conflict, Family Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2021, 33, 47–65.

- Dávila, M.C.; Finkelstein, M. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Well-Being: Preliminary Results. Int. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 3, 45–51.

- Bachrach, D.G.; Powell, B.C.; Bendoly, E.; Richey, R.G. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Performance Evaluations: Exploring the Impact of Task Interdependence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 193–201.

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Pasamar, S.; Donate, M.J. Well-Being in Times of Ill-Being: How AMO HRM Practices Improve Organizational Citizenship Behaviour through Work-Related Well-Being and Service Leadership. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021; ahead-of-print.

- Tordera, N.; Peiró, J.M.; Ayala, Y.; Villajos, E.; Truxillo, D. The Lagged Influence of Organizations’ Human Resources Practices on Employees’ Career Sustainability: The Moderating Role of Age. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103444.

More