Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Sirius Huang and Version 1 by Cinzia Giacometti.

A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) requires the macroscopic visualization of gastric-appearing mucosa in the esophagus and the identification of intestinal metaplasia on histologic examination. Histologic diagnosis of BE dysplasia can be challenging due to sampling error, pathologists’ experience, interobserver variation, and difficulty in histologic interpretation: all these problems complicate patient management.

- intestinal metaplasia

- Barrett’s dysplasia

- esophageal dysplasia

1. Introduction

When assessing the efficacy of interventions for any medical condition, it is crucial to take into consideration the natural progression of the condition. In the case of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), the emergence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is the most significant and relevant outcome. In Western countries, BE—the only recognized precursor of EAC—affects 2–7% of adults [1[1][2],2], and over the last decade, there have been significant advances in the comprehension of biology and pathology of the esophagus and GEJ in response to injury sustained as a result of chronic gastresophageal reflux disease (GERD) [3], even if some studies revealed that BE prevalence is also substantial in patients without GERD [4] It is believed that BE progresses to EAC in stages, with dysplasia (low-grade—LGD and high-grade—HGD) occurring before the development of EAC. It is crucial to monitor patients with recognized and established BE to prevent the development of EAC. Some data suggest that surveillance can help improve patients’ outcomes [5]. There is significant variability in the reported rate of progression of LGD, which is mainly attributable to the significant differences in the way LGD is classified by pathologists [6], so the risk of progression for LGD depends on the accuracy of its diagnosis. The diagnosis may vary depending on the experience and expertise of the local practitioners: the diagnosis of LGD in community centers can be unreliable. Therefore, when the diagnosis of LGD is made, it is recommended that biopsies should be repeated and examined by at least two expert gastrointestinal pathologists. If LGD is conclusively diagnosed, the annual risk of progression to cancer may be around 1–3% [7,8,9][7][8][9]. The progression rate from LGD to HGD/EAC is higher and is estimated in about 5–10% [10]. Even if the diagnosis of HGD is more straightforward, HGD can be easily over-diagnosed [11].

Endoscopic surveillance and treatment for Barrett’s esophagus (BE), LGD, HGD, and EAC rely heavily on the accuracy of histological diagnosis.

2. Barrett’s Esophagus

2.1. Guidelines and Definitions: A Long Journey to Standardization

Difficulties in unambiguously establishing the exact location and origin of SCJ, EGJ, and cardia are responsible for differences in definitions and diagnosis of BE worldwide. The endoscopic diagnosis of BE is made by recognizing a velvet-like, salmon-colored mucosa in the distal esophagus, which is in continuity with the gastric folds. Thus, the endoscopic defining of the landmark of GEJ constitutes a significant difference between the guidelines regarding the endoscopic diagnosis and pathological findings of BE and follow-up methods for the early detection of Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma. Many have been published (or revised) around the world in the last few years: in Europe by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG); in the United States by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG); in Japan by the Japanese Esophageal Society (JES); in the Asian-pacific area by the Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology (APAGE). As the endoscopic diagnostic methods have not been standardized, each guideline differs from the other (Table 1) regarding the length of columnar epithelium, endoscopic landmark, and the requirement of intestinal metaplasia to define BE [28,29,30,31,32,33][12][13][14][15][16][17].Table 1.

Diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) according to different guidelines.

| Society | Length Criteria | Landmark | Intestinal Metaplasia |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASGE | Any | PMGF | Required |

| ACG | ≥1 cm | PMGF | Required |

| AGA | Any | PMGF | Required |

| ESGE | ≥1 cm | PMGF | Required |

| BSG | ≥1 cm | PMGF | Not Required |

| APAGE | ≥1 cm | PMGF | Not Required |

| JES | Any | DEPV | Not Required |

ASGE—American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; ACG—American College of Gastroenterology; AGA—American Gastroenterological Association; ESGE—European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; BSG—British Society of Gastroenterology; APAGE—Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology; JES—Japanese Esophageal Society; PMGF—proximal margin of gastric folds; DEPV—distal end of palisade vessel.

During the recent Kyoto international consensus meeting, some significant issues were addressed to standardize the diagnosis of BO worldwide. As an endoscopic landmark, the consensus meeting adopted DEPV as more appropriate for defining GEJ since it has a more valid anatomical basis than the landmark [34][18].

However, some scientific societies (BSG, APAGE, JES) do not consider the presence of histologically detected IM to diagnose BE (Table 1). This position relies on the demonstration that cardiac mucosa, considered the normal lining of the gastric cardia, also found in embryos and fetuses [38[22][23][24],39,40], can also have intestinal-type histochemical features and abnormalities in DNA content, it appears to be a GERD-induced change, and it is the substrate for the development of GEJ adenocarcinoma [41][25].

The Kyoto International Consensus Meeting discarded IM for the assessment of BE histological diagnosis [34][18].

However, some scientific societies (BSG, APAGE, JES) do not consider the presence of histologically detected IM to diagnose BE (Table 1). This position relies on the demonstration that cardiac mucosa, considered the normal lining of the gastric cardia, also found in embryos and fetuses [38[22][23][24],39,40], can also have intestinal-type histochemical features and abnormalities in DNA content, it appears to be a GERD-induced change, and it is the substrate for the development of GEJ adenocarcinoma [41][25].

The Kyoto International Consensus Meeting discarded IM for the assessment of BE histological diagnosis [34][18].

High-grade dysplasia (HGD) is characterized by significant cytological atypia and widespread architectural changes. The cells have enlarged nuclei, often up to three to four times the size of lymphocytes, with full-thickness nuclear stratification in both the base and surface epithelium. There is also nuclear pleomorphism, irregular nuclear contours, and a substantial loss of polarity. Mitotic activity is increased, and atypical mitoses are frequently observed. Additionally, intraluminal necrosis may be present. The crypts in high-grade dysplasia may vary in size and shape, appear crowded, or contain marked budding, angulation, back-to-back growth, and cribriforming. The diagnosis of HGD can be made based on either high-grade cytological or architectural aberrations. However, most cases show a combination of both cytological and architectural abnormalities [41][25].

High-grade dysplasia (HGD) is characterized by significant cytological atypia and widespread architectural changes. The cells have enlarged nuclei, often up to three to four times the size of lymphocytes, with full-thickness nuclear stratification in both the base and surface epithelium. There is also nuclear pleomorphism, irregular nuclear contours, and a substantial loss of polarity. Mitotic activity is increased, and atypical mitoses are frequently observed. Additionally, intraluminal necrosis may be present. The crypts in high-grade dysplasia may vary in size and shape, appear crowded, or contain marked budding, angulation, back-to-back growth, and cribriforming. The diagnosis of HGD can be made based on either high-grade cytological or architectural aberrations. However, most cases show a combination of both cytological and architectural abnormalities [41][25].

2.2. Intestinal Metaplasia, or Not: Still a Diagnostic Requirement?

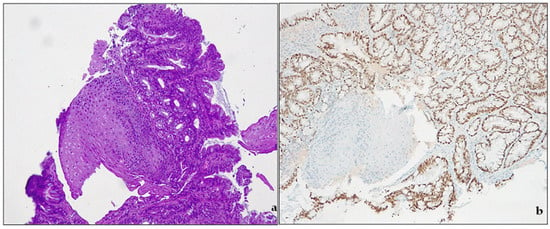

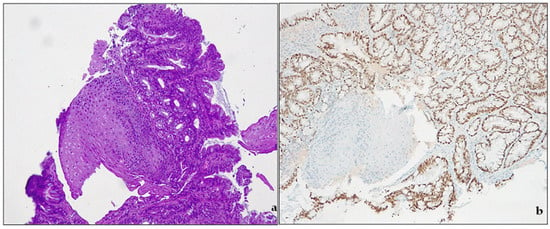

Metaplasia is classically defined as “the conversion, during postnatal life, of one differentiated cell type to that of another” [35][19]. The concept of metaplasia deals with three main notions: (a) normal tissue is located in the wrong place; (b) that tissue appeared in the wrong place during postnatal life; and (c) the presence of that tissue in that wrong place is due to its actual development there, rather than its migration from an adjacent area [36][20]. By these definitions, true metaplasia is only that which derives from cellular transformations due to changes in developmental commitment. In human pathology, metaplasia is usually associated with tissue chronic damage and arises most often in regenerating tissues. Chronic damages, metaplasia and cancer development are a well-known pathway in clinical settings: BE is one of them [37][21]. In the debate around the definitions of BE, intestinal metaplasia (IM) plays a pivotal role. IM (Figure 31) indicates the presence of a specialized (intestinal) metaplastic tissue in the distal esophagus. IM is a known risk factor for developing gastric or esophageal cancer.

Figure 31.

Barrett’s esophagus. (

a

) intestinal metaplasia. H&E, original magnification 100×; (

b

) CDX2 expression, original magnification 100×.

2.3. Molecular Pathway: From Normal Tissue to Metaplasia: Transdifferentiation, Transcommitment and Cell of Origin

A possible explanation for BE metaplasia is transdifferentiation, where fully differentiated esophageal squamous cells transform into fully differentiated columnar cells (Campo, 32). In Barrett’s esophagus, differentiated cells can regress to become immature progenitor cells, leading to increased expression of genes such as CDX1 and c-Myc, compared to the normal epithelium of the esophagus (Campo, 33). CDX2, a transcription factor belonging to the caudal-related homeobox gene family, is thought to be an early marker of intestinal differentiation and may play a role in the development of intestinal metaplasia (Campo, 34). Transdifferentiation in the esophagus may occur in two stages: first, completely differentiated, mature, squamous cells acquire progenitor cell-like plasticity; secondly, they can re-enter the cell cycle to repair injured tissues by transforming into a metaplastic tissue that might be more resistant to GERD. These cycles may repeat over time. Murine models with induced gastric HP infection showed a complex pattern of peptide expression, such as trefoil factor 2 (TFF2). During the answer to the injury, the cells silence mTORC1 signaling, enabling autophagy to recycle cellular material to synthesize new structures. After that, they express genes associated with metaplasia, such as SOX9 and TFF2, and then reactivate mTORC1 signaling to re-enter the cell cycle. Trefoil proteins may be important in protecting and repairing gastrointestinal tract [41,42][25][26]. In the 1990s, some investigators discovered the multilayered epithelium (MLE), a peculiar histologic entity observed at the SCJ. It comprised four to eight layers of stratified squamous cells at the bottom of of mucin-containing epithelial cells with microvilli. These cells are different from Barrett’s intestinalized and normal esophageal squamous cells [37,38][21][22]. This MLE is not visible in intestinal metaplasia that is related to chronic gastritis. Also, its immunohistochemical CK7, CK14, CK19, and CK20 expression pattern is similar to the epithelium of the esophageal gland duct. Some data suggest that the preservation of CK7 and the loss of CK20 expression occurs in the progression of metaplasia to dysplasia and carcinoma, indicating a de-differentiation towards a progenitor cell phenotype Campo [39,40][23][24]. The process by which immature progenitor cells that can proliferate and differentiate into different cell types are reprogrammed to alter their regular differentiation pattern is transcommitment [31][15]. There are four categories of candidates that could be progenitor cells that give rise to Barrett’s metaplasia: (1) progenitor cells native to the esophagus (including basal cells of the squamous epithelium or cells of esophageal submucosal glands and their ducts); (2) progenitor cells native to the gastric cardia that might migrate into the esophagus in response to reflux damages; (3) specialized populations of cells at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). (4) bone marrow progenitor cells [41][25].3. Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus

3.1. Definition

Barrett dysplasia is defined by a morphologically unequivocal neoplastic epithelium without invasion, occurring in an area of metaplastic columnar epithelium in the esophagus [43][27]. Endoscopically, dysplasia is usually associated with an irregular pit pattern when analyzed with NBI magnification [44,45][28][29].3.2. Type of Dysplasia

3.2.1. Intestinal-Type Dysplasia

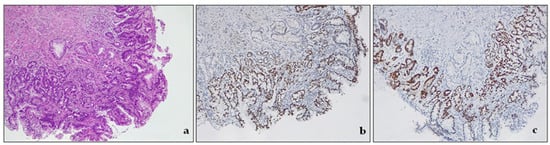

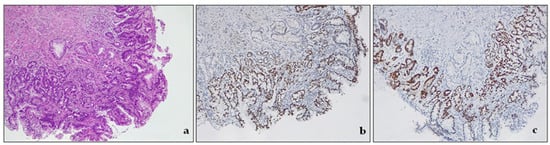

Intestinal dysplasia is a common form of dysplasia in BE, and it resembles a typical colonic adenoma. It is made up of columnar cells that have intestinal differentiation and goblet cells. In contrast, foveolar or non-intestinal gastric dysplasia demonstrates glands closely packed with a single layer of columnar cells and few or no interspersed goblet cells. The basal nuclei are round or oval with little stratification or pleomorphism, and the nuclei are vesicular with prominent nucleoli [3,46][3][30]. Low-grade dysplasia (LGD) is a pathological condition characterized by cells with nuclear enlargement, elongation, hyperchromasia, and stratification but with retained nuclear polarity (Figure 42). The dysplastic crypts typically show minimal architectural changes, and there is still evident lamina propria between them. The nuclei are slightly enlarged, and the number of mitoses generally increases, but they still appear normal. The cytoplasm is usually eosinophilic and depleted of mucin. The number of goblet cells may vary from very few to numerous [3,43][3][27].

Figure 42. Intestinal type dysplasia, low grade. (a) The glands are packed, but lamina propria is still detectable between the glands. There are some scattered residual goblet cells. H&E. Original magnification 200×; (b) CDX2 expression in metaplastic glandular epithelium, devoid of goblet cells. Original magnification 200×; (c) p53 expression in metaplastic glandular epithelium, devoid of goblet cells. Original magnification 200×.

3.2.2. Non-Intestinal Dysplasia

Foveolar dysplasia, which is non-intestinal, does not exhibit any cytologic characteristics of intestinal differentiation. It demonstrates mucinous (also known as “foveolar”) cytoplasmic changes, frequently with a complete absence of goblet cells. Morphologically, it resembles the gastric foveolar epithelium [44][28]. Foveolar dysplasia appears as an epithelium composed of cells with abundant mucinous cytoplasm and only a few goblet cells. The cellular composition consistently displays a homogeneous, singular layer. Their size is relatively small or moderately enlarged, featuring round to oval-shaped nuclei positioned at the base with no discernible fluctuations in size or shape. The surface epithelium is invariably implicated, while the bases of the crypts may be spared. Identifying LGD foveolar type can be challenging as it closely resembles non-neoplastic, gastric cardia mucosa, particularly in an inflammatory backdrop [47][31]. In one study by Khoer et al., foveolar dysplasia was found to be highly associated with a complete gastric immunophenotype (MUC5A+, MUC2−), while “classic” adenomatous/intestinal dysplasia was associated with a complete intestinal immunophenotype [48][32]. HGD is characterized by large, round to oval nuclei, open chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli, and increased mitoses. There is no significant loss of polarity, stratification, and pleomorphism. Even in HGD, the cells tend to retain a regular appearance. The most striking feature is architectural: the crypts are more compact, elongated and show extensive branching and complexity without intervening lamina propria [3].3.3. Diagnostic Categories

In accordance with growing evidence that BE was a complex entity, Reid et al., in 1988, via a preliminary consensus conference, defined a five-tiered histologic classification of BE’s dysplasia: 1. negative for dysplasia; 2. indefinite for dysplasia; 3. low-grade dysplasia; 4. high-grade dysplasia; 5. Intramucosal carcinoma [49][33]. Ten years later, in order to “develop a common worldwide terminology for gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia”, in 1998, a consensus meeting was held in Vienna [50][34]. The Vienna classification is still in use [43][27] and pathologists should report dysplasia according to the four diagnostic categories proposed: 1. negative for dysplasia; 2. indefinite for dysplasia; 3. low-grade dysplasia; 4. high-grade dysplasia (Table 2). The rationale for this tiered approach is to stratify patients into categories of increasing risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC).| Vienna | Reid |

|---|---|

| Negative for neoplasia/dysplasia | Negative for dysplasia |

| Indefinite for neoplasia/dysplasia | Indefinite for dysplasia |

| Non-invasive low-grade neoplasia (low-grade adenoma/dysplasia) | Low-grade dysplasia |

| Non-invasive high-grade neoplasia | High-grade dysplasia |

|

-

Negative for dysplasia. This diagnosis is made when the biopsy represents either columnar epithelium with no cell atypia or reactive (hyperplastic/regenerative) changes.

-

Indefinite for dysplasia. This category reflects the uncertainty of the diagnosis. As the real nature of the lesion cannot be assessed, follow-up should be suggested in the report [50][34]. In some settings, biopsy interpretation can be highly challenging for pathologists. Active inflammation, ulceration, or post-ulcer healing may determine profound changes in tissue. This descriptive, provisional category should apply only to cases where the pathologist cannot clearly decide whether the lesion is negative for dysplasia (hyperplastic/regenerative) or genuinely dysplastic. The grade of uncertainty may be due to inadequate biopsy sampling or cytological atypia and structural alterations with equivocal interpretation. This diagnosis must be followed by short-term resampling and second opinion and not be used as a “waste-basket” category.

-

Low-grade dysplasia—LGD. The cells in LGD display nuclear enlargement, elongation, hyperchromasia, and stratification, but their nuclear polarity is retained (Figure 42). Although the dysplastic crypts show minimal architectural changes, the lamina propria between them is still visible. The nuclei are slightly enlarged, and the number of goblet cells present may range from a few scattered ones to numerous.

-

High-grade dysplasia—HGD. HGD is characterized by striking cytological atypia and wider architectural changes. The cells have markedly enlarged nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, irregular nuclear contours, and loss of polarity. Mitoses are increased in number and are often atypical. The crypts may appear crowded, and/or may contain marked budding or angulation, back-to-back growth, and cribriforming.

3.4. Ancillary Techniques

Some ancillary diagnostic markers, mainly immunohistochemical, have been investigated to facilitate BE diagnosis: proliferation markers such as Ki67, genetic mutations (p53, p16, Kras, APC, B catenin), some growth factors, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), and alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR). p53 is a transcription factor expressed by the tumor suppressor gene TP53 (chromosome 17p). The TP53 gene encodes p53, which prevents mutations. Normal cells (wild type) have low levels of this protein in their nuclei. The gene and protein are upregulated in the presence of DNA damage or stress. In dysplastic cells, mutations of TP53 can be detected by IHC, which may show a different pattern of expression: (a) complete loss, absent (null) pattern, completely negative staining; (b) cytoplasmic patter; (c) mutation pattern, with increased expression and positive staining. Recently, Redston et al. proposed a scoring method for p53 expression in BE [51,52,53][35][36][37]. Even if promising, p53 provides variable results (both false positive and false negative): its use to diagnose dysplasia in clinical practice is still controversial. More recently, biomarkers different by IHC were investigated, as Wide Area Transepithelial Sampling with Three-Dimensional Computer-Assisted Analysis (WATS3D), TissueCypher, mutational load analysis (BarreGen), fluorescence in situ hybridization, and DNA content abnormalities as detected via DNA flow cytometry. These tests provide information that cannot be assessed based on morphology alone and may offer more precise surveillance in those cases with an unsatisfactory (IND) diagnosis or LGD at histology [51][35]. At present, however, in routine practice, morphologic assessment of dysplasia remains the gold standard for evaluating dysplasia.3.5. Molecular Pathway: From Metaplasia to Adenocarcinoma

Despite the peculiarity of its history, the difficulties in determining the cell of origin of BE, and the numerous debates about clinical diagnosis, histological diagnosis, clinical surveillance, etc., in recent years, there is a growing body of evidence that EAC, which is thought to arise in the BE context, shares molecular similarities with GEJ and gastric cancers, with a progressive increase in chromosomal instability phenotype [54][38]. For this reason, they should be considered as a single entity for clinical trials of neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or systemic therapies. Many different oncogenes (c-Myc, Cyclins), growth factors (FGFR, erb-B2/Her2-neu), and tumor suppressors (p53, p16, p15, p27) have been identified during the progression from metaplasia to dysplasia and then EAC [55][39]. The process of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma involves distinct stages, from BE to primary tumors and advanced metastatic disease. The mucosa in the distal esophagus can be injured by reflux-induced cytokine damage [56,57,58,59][40][41][42][43]. Bile acid exposure in an acidic environment increases reactive oxygen species in keratinocytes and the metaplastic epithelium in BE [60][44]. This, in turn, leads to HIF-2α stabilization [61][45], nuclear translocation, binding to HIF-responsive elements, and the synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines. HIF-2α is responsible for regulating the inflammatory response to reflux injury, which is linked to NF-κB signaling via p65 phosphorylation. The activation of NF-κB in the distal esophagus leads to persistent inflammation and triggers the development of intestinal metaplasia through the activation of CDX2. CDX2 plays a crucial role in intestinal differentiation and may be a downstream target of NF-κB, as it contains a binding site for NF-κB [62,63][46][47]. Exposure to bile acids in an acidic environment can cause oxidative stress in squamous and metaplastic epithelia in individuals with Barrett’s esophagus (BE). This can lead to DNA damage, particularly double-strand breaks in DNA [62][46]. Neoplastic progression in the metaplastic segment is mainly driven by TP53 mutations, which can cause a significant increase in genetic abnormalities. TP53 mutations make it easier for other genetic mechanisms to drive carcinogenesis in BE. Loss-of-function mutations in TP53 can lead to exponential growth in several mutations due to impaired mechanisms of DNA repair and apoptosis. Mutations in TP53 serve as a point from which different genetic mechanisms can be realized. In their simplest form, mutational signatures are single-base substitutions in a trinucleotide context. This is reflected in unique patterns of patterns of nucleotide substitutions or larger chromosomal rearrangements. The T>G and T>C substitutions dominate the mutational landscape and is linked with TP53 mutations, increased proliferation, genomic instability, and disease progression [64][48]. DNA damage, resulting from both internal and external mutational processes during an individual’s life, is recorded in the genome of cancer cells. Obesity has been identified as a major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma due to anatomical factors such as increased abdominal and intraperitoneal adiposity and hiatal hernia formation, which predispose patients to increased gastro-esophageal reflux. Moreover, obesity promotes cancer progression through insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, and the production of adipokines—hormones associated with fat. Additionally, the signaling of Human Epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) plays a role in cancer development. The incidence of esophageal cancer can be significantly increased by hyperinsulinemia in the presence of duodenal reflux. In such cases, insulin receptor (IR) and IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) tend to be overexpressed. It appears that IGF1R is responsible for cancer onset through the activation of the ERK1/2 mitogenic pattern. The upregulation of IGF1R and HER2 in hyperinsulinemia could also increase the likelihood of forming IGF1R/HER2 heterodimers, which support cell growth, proliferation, and progression in esophageal carcinogenesis.References

- Hayeck, T.J.; Kong, C.Y.; Spechler, S.J.; Gazelle, G.S.; Hur, C. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the US: Estimates from a simulation model confirmed by SEER data. Dis. Esophagus 2010, 23, 451–457.

- Sawas, T.; Killcoyne, S.; Iyer, P.G.; Wang, K.K.; Smyrk, T.C.; Kisiel, J.B.; Qin, Y.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Rustgi, A.K.; Costa, R.J.; et al. Identification of Prognostic Phenotypes of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in 2 Independent Cohorts. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1720–1728.e4.

- Naini, B.V.; Souza, R.F.; Odze, R.D. Barrett’s Esophagus: A Comprehensive and Contemporary Review for Pathologists. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, e45–e66.

- Saha, B.; Vantanasiri, K.; Mohan, B.P.; Goyal, R.; Garg, N.; Gerberi, D.; Kisiel, J.B.; Singh, S.; Iyer, P.G. Prevalence of Barrett’s Esophagus and Adenocarcinoma with and without Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023.

- El-Serag, H.B.; Naik, A.D.; Duan, Z.; Shakhatreh, M.; Helm, A.; Pathak, A.; Hinojosa-Lindsey, M.; Hou, J.; Nguyen, T.; Chen, J.; et al. Surveillance endoscopy is associated with improved outcomes of oesophageal adenocarcinoma detected in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2016, 65, 1252–1260.

- Vennalaganti, P.; Kanakadandi, V.; Goldblum, J.R.; Mathur, S.C.; Patil, D.T.; Offerhaus, G.J.; Meijer, S.L.; Vieth, M.; Odze, R.D.; Shreyas, S.; et al. Discordance Among Pathologists in the United States and Europe in Diagnosis of Low-Grade Dysplasia for Patients with Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 564–570.e4.

- Sharma, P.; Falk, G.W.; Weston, A.P.; Reker, D.; Johnston, M.; Sampliner, R.E. Dysplasia and cancer in a large multicenter cohort of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 4, 566–572.

- de Jonge, P.J.; van Blankenstein, M.; Looman, C.W.; Casparie, M.K.; Meijer, G.A.; Kuipers, E.J. Risk of malignant progression in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: A Dutch nationwide cohort study. Gut 2010, 59, 1030–1036.

- Khoshiwal, A.M.; Frei, N.F.; Pouw, R.E.; TissueCypher SURF LGD Study Pathologists Consortium; Smolko, C.; Arora, M.; Siegel, J.J.; Duits, L.C.; Critchley-Thorne, R.J.; Bergman, J. The Tissue Systems Pathology Test Outperforms Pathology Review in Risk Stratifying Patients with Low-Grade Dysplasia. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1168–1179.e6.

- Duits, L.C.; van der Wel, M.J.; Cotton, C.C.; Phoa, K.N.; Ten Kate, F.J.W.; Seldenrijk, C.A.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; Visser, M.; Meijer, S.L.; Mallant-Hent, R.C.; et al. Patients with Barrett’s Esophagus and Confirmed Persistent Low-Grade Dysplasia Are at Increased Risk for Progression to Neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 993–1001.e1.

- Sangle, N.A.; Taylor, S.L.; Emond, M.J.; Depot, M.; Overholt, B.F.; Bronner, M.P. Overdiagnosis of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: A multicenter, international study. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 758–765.

- Asge Standards of Practice Committee; Qumseya, B.; Sultan, S.; Bain, P.; Jamil, L.; Jacobson, B.; Anandasabapathy, S.; Agrawal, D.; Buxbaum, J.L.; Fishman, D.S.; et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 90, 335–359.e2.

- di Pietro, M.; Fitzgerald, R.C.; BSG Barrett’s Guidelines Working Group. Revised British Society of Gastroenterology recommendation on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus with low-grade dysplasia. Gut 2018, 67, 392–393.

- Kusano, C.; Singh, R.; Lee, Y.Y.; Soh, Y.S.A.; Sharma, P.; Ho, K.Y.; Gotoda, T. Global variations in diagnostic guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus. Dig. Endosc. 2022, 34, 1320–1328.

- Sharma, P.; Shaheen, N.J.; Katzka, D.; Bergman, J. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Treatment of Barrett’s Esophagus with Dysplasia and/or Early Cancer: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 760–769.

- Saftoiu, A.; Hassan, C.; Areia, M.; Bhutani, M.S.; Bisschops, R.; Bories, E.; Cazacu, I.M.; Dekker, E.; Deprez, P.H.; Pereira, S.P.; et al. Role of gastrointestinal endoscopy in the screening of digestive tract cancers in Europe: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy 2020, 52, 293–304.

- Fock, K.M.; Talley, N.; Goh, K.L.; Sugano, K.; Katelaris, P.; Holtmann, G.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Sharma, P.; Ang, T.L.; Hongo, M.; et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: An update focusing on refractory reflux disease and Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2016, 65, 1402–1415.

- Sugano, K.; Spechler, S.J.; El-Omar, E.M.; McColl, K.E.L.; Takubo, K.; Gotoda, T.; Fujishiro, M.; Iijima, K.; Inoue, H.; Kawai, T.; et al. Kyoto international consensus report on anatomy, pathophysiology and clinical significance of the gastro-oesophageal junction. Gut 2022, 71, 1488–1514.

- Slack, J.M. Epithelial metaplasia and the second anatomy. Lancet 1986, 2, 268–271.

- Slack, J.M. Metaplasia and somatic cell reprogramming. J. Pathol. 2009, 217, 161–168.

- Burke, Z.D.; Tosh, D. Barrett’s metaplasia as a paradigm for understanding the development of cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2012, 22, 494–499.

- De Hertogh, G.; Van Eyken, P.; Ectors, N.; Tack, J.; Geboes, K. On the existence and location of cardiac mucosa: An autopsy study in embryos, fetuses, and infants. Gut 2003, 52, 791–796.

- Park, Y.S.; Park, H.J.; Kang, G.H.; Kim, C.J.; Chi, J.G. Histology of gastroesophageal junction in fetal and pediatric autopsy. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2003, 127, 451–455.

- Zhou, H.; Greco, M.A.; Daum, F.; Kahn, E. Origin of cardiac mucosa: Ontogenic consideration. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2001, 4, 358–363.

- Que, J.; Garman, K.S.; Souza, R.F.; Spechler, S.J. Pathogenesis and Cells of Origin of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 349–364.e1.

- Dunn, L.J.; Jankowski, J.A.; Griffin, S.M. Trefoil Factor Expression in a Human Model of the Early Stages of Barrett’s Esophagus. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 1187–1194.

- Odze, R. Barrett’s Dysplasia. In Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board; WHO Classification of Tumours Series; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2019; Volume 1.

- Oyama, T. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of superficial Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma: Japanese perspective. Dig. Endosc. 2022, 34 (Suppl. S2), 27–30.

- Iyer, P.G.; Chak, A. Surveillance in Barrett’s Esophagus: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 707–718.

- Brown, I.S.; Whiteman, D.C.; Lauwers, G.Y. Foveolar type dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 834–843.

- Patil, D.T.; Bennett, A.E.; Mahajan, D.; Bronner, M.P. Distinguishing Barrett gastric foveolar dysplasia from reactive cardiac mucosa in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 1146–1153.

- Khor, T.S.; Alfaro, E.E.; Ooi, E.M.; Li, Y.; Srivastava, A.; Fujita, H.; Park, Y.; Kumarasinghe, M.P.; Lauwers, G.Y. Divergent expression of MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, CD10, and CDX-2 in dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinomas with intestinal and foveolar morphology: Is this evidence of distinct gastric and intestinal pathways to carcinogenesis in Barrett Esophagus? Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 331–342.

- Reid, B.J.; Haggitt, R.C.; Rubin, C.E.; Roth, G.; Surawicz, C.M.; Van Belle, G.; Lewin, K.; Weinstein, W.M.; Antonioli, D.A.; Goldman, H.; et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Hum. Pathol. 1988, 19, 166–178.

- Schlemper, R.J.; Riddell, R.H.; Kato, Y.; Borchard, F.; Cooper, H.S.; Dawsey, S.M.; Dixon, M.F.; Fenoglio-Preiser, C.M.; Flejou, J.F.; Geboes, K.; et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000, 47, 251–255.

- Choi, W.T.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Montgomery, E.A. Utility of ancillary studies in the diagnosis and risk assessment of Barrett’s esophagus and dysplasia. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1000–1012.

- Tomaszewski, K.J.; Neyaz, A.; Sauder, K.; Rickelt, S.; Zhang, M.L.; Yilmaz, O.; Crotty, R.; Shroff, S.; Odze, R.; Mattia, A.; et al. Defining an abnormal p53 immunohistochemical stain in Barrett’s oesophagus-related dysplasia: A single-positive crypt is a sensitive and specific marker of dysplasia. Histopathology 2023, 82, 555–566.

- Qiu, Q.; Guo, G.; Guo, X.; Hu, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; She, J. P53 Deficiency Accelerate Esophageal Epithelium Intestinal Metaplasia Malignancy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 882.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 2017, 541, 169–175.

- Souza, R.F.; Spechler, S.J. Concepts in the prevention of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005, 55, 334–351.

- Souza, R.F.; Spechler, S.J. Oesophagus: A new candidate for the progenitor cell of Barrett metaplasia. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 7–8.

- Souza, R.F. Reflux esophagitis and its role in the pathogenesis of Barrett’s metaplasia. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 767–776.

- Souza, R.F. From Reflux Esophagitis to Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Dig. Dis. 2016, 34, 483–490.

- Souza, R.F. The role of acid and bile reflux in oesophagitis and Barrett’s metaplasia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 348–352.

- Feagins, L.A.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Hormi-Carver, K.; Thomas, T.; Terada, L.S.; Spechler, S.J.; Souza, R.F. Mechanisms of oxidant production in esophageal squamous cell and Barrett’s cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 2008, 294, G411–G417.

- Ling, F.C.; Khochfar, J.; Baldus, S.E.; Brabender, J.; Drebber, U.; Bollschweiler, E.; Hoelscher, A.H.; Schneider, P.M. HIF-1alpha protein expression is associated with the environmental inflammatory reaction in Barrett’s metaplasia. Dis. Esophagus 2009, 22, 694–699.

- Kazumori, H.; Ishihara, S.; Rumi, M.A.; Kadowaki, Y.; Kinoshita, Y. Bile acids directly augment caudal related homeobox gene Cdx2 expression in oesophageal keratinocytes in Barrett’s epithelium. Gut 2006, 55, 16–25.

- Huo, X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.I.; Lynch, J.P.; Strauch, E.D.; Wang, J.Y.; Melton, S.D.; Genta, R.M.; Wang, D.H.; Spechler, S.J.; et al. Acid and bile salt-induced CDX2 expression differs in esophageal squamous cells from patients with and without Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 194–203.e1.

- Abbas, S.; Pich, O.; Devonshire, G.; Zamani, S.A.; Katz-Summercorn, A.; Killcoyne, S.; Cheah, C.; Nutzinger, B.; Grehan, N.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; et al. Mutational signature dynamics shaping the evolution of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4239.

More