Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a growing problem nowadays, and diabetic retinopathy (DR) is its predominant complication.

- diabetes

- proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- retina

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- asymmetric dimethylarginine

- microRNAs

1. Introduction

2. Risk Factors

2.1 Duration of Diabetes and Hyperglycemia

The most relevant risk factors for the development of diabetic retinopathy include the duration of diabetes, greater uncontrolled hyperglycemia as indicated by high HbA1c levels, and the presence of hypertension [6][12]. Research showed that maintaining proper blood glucose control has a notably stronger effect on diabeticDR retinopathy pprevention compared to controlling blood pressure [7][8][13,14]. TResearche risk of diabetic retinopathy suggests that the risk gradually increases over time, making regular eye examinations essential for individuals with diabetes identified for more than a decade.2.2 Nephropathy and High BMI

Other well-known risk factors for diabeticDR retinopathy aare nephropathy and high body mass BMI index (BMI) [6][9][12,15]. Although there are no definite associations between traditional lipid markers and diabetic retinopathyDR, several studies over the years have suggested that lipid-lowering therapy might be an effective adjunctive agent for diabetic retinopathy aDR and may reduce the risk of its development [10][11][12][13][14][16,17,18,19,20]. Both diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy are complications of DM resulting from microvascular damage through, i.e., inflammation and oxidative stress attributed to uncontrolled blood glucose levels. These mechanisms can result in the simultaneous occurrence of nephropathy and DM, consequently, it is important to regularly screen patients with severe nephropathy for eventual diabeticDR retinopathy development [3][15][3,21].2.3 Smoking

Smoking is an additional risk factor for diabetic retinopathyDR. A study by Xiaoling et al., which in the study identifiedying and compareding 73 studies involving type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients, established a clear association between smoking and diabetic retinopathyDR. In type 1 diabetes, the risk of diabetic retinopathy DR significantly increased among smokers compared to non-smokers. Surprisingly, in type 2 diabetes, the risk of diabetic retinopathy DR was found to be lower in smokers than in non-smokers [16][22]. However, this result should not change the importance of smoking cessation for overall health benefits.2.4 Pregnancy

FResearch findings indicate that for women with diabetes, pregnancy can pose an additional risk factor for developing or worsening already existing diabetic retinopathyDR. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in DR in women with type 1 diabetes is higher than in type 2, and it tends to worsen in type 1 diabetic women compared to type 2 diabetes [15][17][21,23]. Consequently, it is crucial for pregnant women with diabetes to closely monitor blood glucose levels and manage the condition effectively. Diabetic retinopathy is a complex condition that requires diligent management to prevent or slow down its progression. By understanding the risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy, presented in Figure 1, individuals with diabetes can take proactive measures to protect their vision. Consistently managing blood sugar levels, blood pressure, and cholesterol and making healthy lifestyle choices, such as quitting smoking, are crucial steps in reducing the risk and severity of diabetic retinopathy.3. Pathophysiology

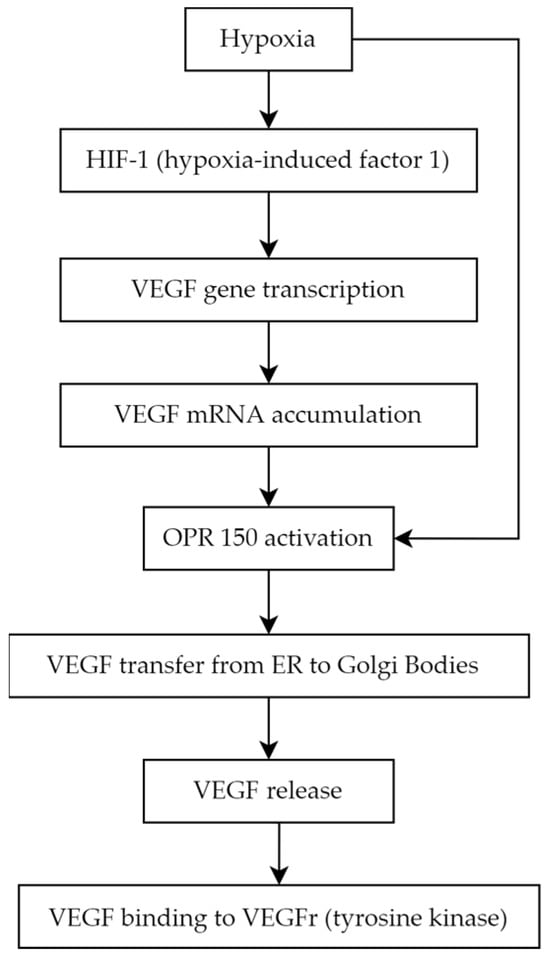

Diabetic retinopathy is primarily associated with microvascular abnormalities and retinal neurodegeneration [18][24]. The neurovascular unit comprises endothelial cells and pericytes, basement membrane, glial cells (including astrocytes and Müller cells), microglia, and neurons. The degeneration of this unit is considered a primary indicator of diabetic retinopathy [19][25]. Hyperglycemia induces non-enzymatic advanced glycation end products creation, increases oxidative stress, and promotes the growth in proinflammatory cytokines, leukocyte migration, and adhesion, which may lead to leukostasis (microcapillaries blockade with leukocytes), moreover, it influences epigenetic modifications [20][21][26,27]. Hyperglycemia, chronic inflammation, and microthrombi induce hypoxia and via hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) upregulates growth factors, mainly VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) [22][28]. The VEGF isoforms promote endothelial cell proliferation during early angiogenesis, and some of its isoforms take part in pathological neovascularization. Hypertension and local retinal vasoconstriction also play a role in diabeticDR retinopathy development and are associated with increased VEGF production [23][31]. The clinical classification divides diabeticDR retinopathy intinto non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [24][32]. In the pathogenesis of NPDR, there is a loss of pericytes, a decrease in their protective role, damage to endothelial cells, and excessive thickening of the basement membrane. These changes lead to vascular leakage and cellular damage [22][25][28,33]. The clinical manifestation of NPDR in the fundoscopic examination typically reveals microaneurysms, which may rupture and cause hemorrhages.4. Molecular Biomarkers

4.1. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Angiogenesis is a complex biological process that underlies the development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, which representings the advanced stage of diabetic retinopathy [26][37]. Among the many pro-angiogenic factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is notably significant. VEGF is a homodimer glycoprotein with a molecular weight of 46 kDa, connected by three disulphide bonds in (cystine-knot form). The VEGF family consists of the following members:- VEGF-A (also called VEGF or vascular permeability factor, the first discovered molecule of the whole family in 1983)

- VEGF-B

- VEGF-C (essential for the formation of lymphatic vessels) [27]

- VEGF-D (known as c-Fos-induced growth factor, FIGF)

- VEGF-E (connected with parapoxvirus Orf, which causes pustular dermatitis) [28]

- placenta growth factor (PGF) [29][30].

4.2. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine

4.3. MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are single-strengthened, non-coding RNA, which affect gene expression regulation. Their suppressor interaction with mRNA usually is associated with 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs), although data claim as well its interaction potential according to different sequences such as gene promoters. Moreover, they also have a regulatory role in transcription and translation processes [70][103]. The creation process of those micromolecules goes from DNA transcription to primary miRNA (pri-mRNA) through precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) leading to mature miRNA formation [71][104]. The role of miRNA in signalization pathways is studied nowadays excessively because of those particles’ multiplicity. Molecular bases of miRNA mechanisms of action are distinct for different miRNAs, and it is possible to distinguish which particles affect which pathway leading to diabetic retinopathyDR, such as affecting cell proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, or basement membrane thickening [72][106]. It has been proven that directly or indirectly particles such as miRNA-9, miRNA-152, miRNA-15b, miRNA-29b-3p, miRNA-199a-3p, miRNA-203a-3p, miRNA-200b-3p, and miRNA-30a-3p downregulate VEGF expression, which lowers the range of active cell-cycle-related proteins and by that protects RMECs (retinal microvascular endothelial cells) from abnormal proliferation [73][107]. In addition, from previously mentioned biomolecules, the alternative pathway to downregulate VEGF is SIRT1 (nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylase) upregulation, which is possible by miRNA-29b-3p and miRNA-34a inhibition, moreover, causing an increase in proinflammatory cytokines [73][107]. MiRNA-34a was evaluated to be an interesting therapeutic target, as in rats with induced diabetic retinopathyDR, its silencing was observed as an apoptosis regulation [74][108]. MiRNA-20a and miRNA-20b were revealed to downregulate VEGF as well but in different mechanisms—first act by Yses-associated protein (YAP)/hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α)/VEGF axis, and second was revealed in the study on rats to be correlated with downregulation of AKT3, lowering VEGF expression [75][76][111,112]. Moreover, it was assessed that rResolvin D1 modulates the intracellular VEGF-related miRNAs—miRNA-20a-3p, miRNA-20a-5p, miRNA-106a-5p, and miRNA-20b—expression of retinal photoreceptors challenged with high glucose [77][113]. The role of the miRNA was biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy was investigatedinvestigated as a DR biomarker using variousdifferent sample types and study ddesigns, comparing differented to various groups based onaccording to diabetes type ( 1 or 2, T1DM or T2DM), patients with diabetes,aDM and healthy individuals, as well studies examining thereferring to DR progression of diabetic retinopathy. In blood serum samples in T1DM patients with and DR and those without diabetic retinopathy, miRNA-211 was the most significant. Additionally was miRNA-211. Then, miRNA-18b and miRNA-19b were found to berevealed as upregulated, along with ; additionally, miRNA-29a, miRNA-148a, miRNA-181a, and miRNA-200a, which also showed notable were revealed to have such an impact [78][79][117,118]. IAccordin T2DM patientsg to T2DM, a study identified was performed and the differences in the following particles were noted: hsa-let-7a-5p, hsa-miRNA-novel-chr5_15976, hsa-miRNA-28-3p, hsa-miRNA-151a-5p, and hsa-miRNA-148a-3p, which w were upregulated compared to DM group without no retinopathy. Notably; however, a panel of the first three miRNA (hsa-let-7a-5p, hsa-miRNA-novel-chr5_15976, and hsa-miRNA-28-3p) showed the highest of them were the closest to help in assessing the diagnostic potential withis as its sensitivity and specificity ofwere as follows: 0.92 and 0.94, respectively [80] [121]. Another study showed that in T2DM patients, diabeticDR retinopathy was associated with increased circulating levels of miRNA-25-3p and miRNA-320b, and decreased levels of miRNA-495-3p [81][122]. Plasma results among T2DM patients regavealed an insight into lower levels of miRNA-29b in those with diabetic retinopathy,e DR group and miRNA-21 was as biomarkers that were significantly associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)PDR. Other parameters that were increased in T2DM patients with diabetic retinopathy included DR were miRNA-93 via SIRT1, and miRNA-21, ands well as miRNA-152 [82][83][126,127]. COn the converseltrary, miRNA-15a, miRNA-20b, miRNA-21, miRNA-24, miRNA-320, miRNA-486, and miRNA-150, miRNA-126, miRNA-191, miRNA-197 weare downregulated in theat group of patients’ plasma samples of[128]. these patients [84]. Importantly, miRNA-150 is observed in the circulation of both T1DM and T2DM patients’ circulation and in the neutral retina. miRNA-150That factor by Elk1 upregulates Elk1,ion stimulatinges proinflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and apoptotic influences. AOtherwise, a lower range of miRNA-150 in serum impacts Elk1 and Myb overexpression, leading to similar pathway resultingresulting in the same as the previously mentioned pathway in microvascular complications and neovascularization, culminating in diabetic retinopathy. Therefore, miRNA-150 leading to DR; so, according to that analysis, it is not only a diagnostic biomarker but alsos well is significantly involved in the diabetic retinopathy pathDR pathogenesis [85][129].4.4. Endothelin-1

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) in its active form is a 21-amino acid hormone that helps to maintain basal vascular tone and metabolic function in healthy individuals [86][132]. ET-1, is an endothelium-derived factor, exhibits with proliferative, profibrotic, and proinflammatory properties [87].[133], and Iit is the most abundantly expressed member of the endothelin family, which includes of proteins (ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3). Immature ET-1 undergoes extensive post-transcriptional processing, culminating in that concludes with cleavage by endothelin converting enzymes (ECEs) and thesubsequent release of mature ET-1 primarily intotoward the interstitial space, with a and in smaller proportion entering, into the circulation [86][132]. ET-1 exeworts its biological effect through two ks on two different ET-1 receptor subtypes:, ETA and ETB, [88]to produce its various biological effects [134]. The first subtype, ETA receptors are, is predominantly localized on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) of blood vessels, where they mediate contractile and proliferative response to ET-1. In contrast,, whereas ETB receptors have a more complex role in osite relation to vascular regulation; they can cause. ETB receptors can lead to vasodilation by via the releasinge of relaxing factors whenif they are present on endothelial cells or vasoconstriction when they are located on VSMCs in certain vascular beds [87][133]. Therefore, the overall effect of ET-1 on different tissues is largely dependent on the expression and relative densities of theseindividual receptor subtypes. ET-1 is a crucial one of the important markers of endothelial dysfunction, a conditionstate characterized by an imdisturbed balance between vasoconstrictors and vasodilators [89][135]. Due to its vasoconstrictive properties, ET-1 has been widely studied in terms forof its role in hypertension and has provenproved clinically significant, as evidenced bye.g., with the use of endothelin receptor antagonists infor the treatingment of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [90][136]. The vasoconstrictive and in turn hypertensive properties of ET-1 can explain a possible link between elevated plasma ET-1 level and retinopathy under ischemia, a finding relevant to diabetic retinopathy, which is thought to be the consequence of retinal ischemia. Animal models have shown that administeringation of ET-1 into the posterior vitreous body or the optic nerve leads to ischemic-related physiological and cellular damages of ischemic origin, including obstruction of retinal blood flow, elevated scotopic b-wave in electroretinogram, and apoptosis of cells in the ganglion cell layer of the retina [91][137].4.5. Advanced Glycation End Products

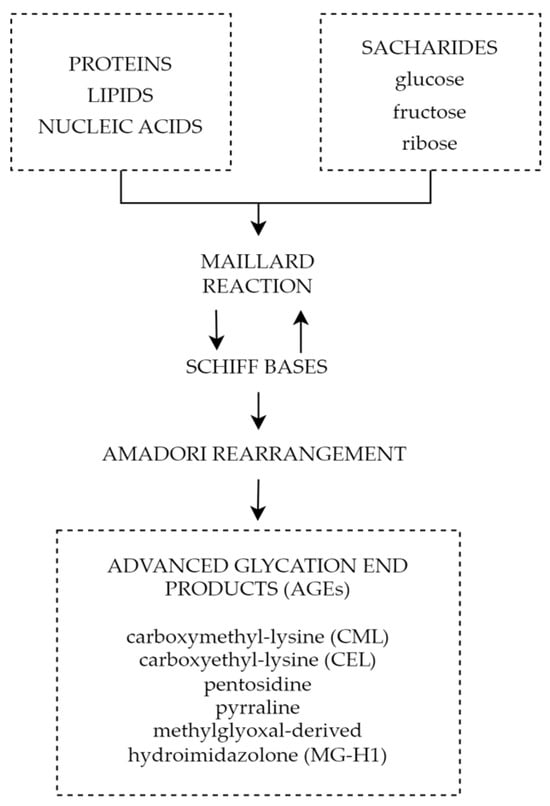

One of the mechanisms connecting chronic hyperglycemia with diabetic retinopathy is the formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Advanced glycation end products are heterogeneous groups of molecules formed from post-translational non-enzymatic modifications of proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids by saccharides including glucose, fructose, and pentose through the Maillard reaction represented by Figure 25 [92][93][148,149]. There are over 20 AGEs identified in human tissues, but some of the most common ones are carboxymethyl-lysine (CML), carboxyethyl-lysine (CEL), pentosidine, pyrraline, and methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone (MG-H1) [94][150]. The characteristic factor of AGEs that distinguishes them from early glycation products, such as glycohemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), is the lack of spontaneous reversion ability, which once derived results in the accumulation in tissues over time [95][151]. Even though the discovery of AGEs dates to the early 20th century, not until the 1980s, the role of AGEs in aging and chronic diseases was recognized [96][152]. The first mention of AGEs and their accumulation in human tissues and their potential role in diabetic complications appeared in 1988 in a scientific article published by Helen Vlassara et al. [97][153]. Since then, AGEs and their involvement in pathophysiological processes have been the subject of extensive research.

5. Summary

ADMA inhibits the activity of NOS, which results in decreased levels of NO and leads to vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction. Increased ADMA levels may be considered an early prognostic factor of diabetes complications such as PDR. The use of ADMA as a biomarker may help in early diagnosis, monitoring, and effective therapeutic management of the disease. Reducing ADMA levels in patients with diabetes may be a new therapeutic target to prevent the development of diabetic retinopathy. Endothelin-1 is another factor with an undoubted relationship to diabetic retinopathy. Increased serum and aqueous humor levels are observed in patients with ET-1 elevation dependent on the severity of the progression of the disease. This, juxtaposed with promising results of ET-1 receptor antagonist animal studies, showcases the potential of ET-1 as a possible target for future therapy. It is important to note that miRNAs are not only supposed to be an innovative predictive biomarker and progression indicator in DR but also a potential therapeutic target. Different miRNAs can be found in T1DM and T2DM as well depending on sample type, moreover, some of them differ depending on DR type. The variety of miRNAs and frequently high amounts of particles involved in several pathogenesis pathways can be at the same time the advantage and disadvantage of that prospective novel biomarkers group; hence, miRNAs panels are more adequate than a single biomarker rating. Finally, advanced glycation end products play a significant role in the pathophysiology of diabetic retinopathy causing impairment of the neurovascular units through reactive oxygen species, inflammatory reactions, and cell death pathways. All the above mechanisms play a significant role not only in diabetic retinal disorders, but also other chronic oxidative-based diseases; therefore, a thorough understanding of their properties and mechanisms will allow advances in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases and most importantly diabetic retinopathy. The above factors and signaling pathways can help to create multimodal and highly specified therapies for patients suffering from DR. It is crucial to investigate molecular agents participating in DR pathogenesis. Hopefully, it will provide the ability to inhibit this progressive disease at its early stage.