Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Atis Verdenhofs.

Green bond investments have a positive impact on carbon reduction and renewable energy supply in the EU OECD countries, and cluster analysis of the European OECD countries indicated a positive relationship between economic performance and overall social and governance (ESG) risk.

- green finance

- green bonds

- benefits

- challenges

1. Introduction

Green finance plays a vital role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 7, in accordance with the UN Agenda 2030 [1]. Green finance projects comply with the framework of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, which focuses on mitigating global warming and is an important basis for the development of the global green bond market [1].

Bibliometric analysis reveals that while the previous articles are mainly related to green finance for developing countries, especially China, the latest ones are related to the risks of climate finance, green bonds and the inclusion of financial issues in the wider regions of energy emissions; these studies provide useful insights for researchers, investors, and policymakers on the importance of environmental investments in promoting economic sustainability [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9].

Due to the growing interest and massive European movement towards a greener society and business, the term green finance is used to describe the different types of products created to support both public and private green investments, as well as initiatives and policies to endorse the execution of environmental mitigation or adaptation projects.

The task of green finance is to strategically include the financial sector in the transition to minimal carbon emissions and to solve climate problems, as well as to increase economic well-being; therefore, it mainly focuses on the environmental aspect of sustainable development [10,11,12,13,14][10][11][12][13][14].

The popularity of green finance stems from the consideration of preventing potential climate crises, making it a priority within each country’s policies and global formats for their cooperation. At the same time, the broader and more organic integration of green finance in the context of economic activity results from the awareness of economics consistency in a given time perspective, if the climate impact of economic activities is ignored, and the risks associated with climate change are not mitigated.

Between 1980 and 2021, weather and climate-related extremes caused economic losses estimated at EUR 560 billion in the EU Member States, of which EUR 56.6 billion is from 2021 alone [15].

Extensive research has been conducted analyzing the relationships between higher spending on human resources, green energy research and development, and the growth of the green economy, emphasizing the intermediary role of green finance. However, the impact of the growth of the green economy on GDP per capita differs between countries with different starting points of economic development, which has not been sufficiently studied [16,17][16][17].

Recent studies prove that green finance promotes the use of renewable energy, with incremental positive effects. However, this effect can be observed in developed countries or emerging economies with strict environmental protection and high influence of green finance [18,19][18][19]. The development of capital markets and bond markets affects the use of renewable energy [20,21][20][21]. However, in general, in recent years, green finance studies have mostly been conducted in developing countries; only a few thorough studies on European countries can be found [19,22,23,24,25][19][22][23][24][25].

2. Benefits of Green Finance

Definitions of green finance can be found in several publications—[45][26] indicates that there are very large differences between the definitions of green finance, as well as different types of organizations, economic sectors define their own indices and definitions of what is described as green finance. According to a 2016 publication by the World Bank Group [46][27], green finance could be broadly defined as “the financing of investments that provide environmental benefits”. Other researchers [47][28], while studying the evolution of green finance and its enablers, concluded that the enablers can be classified under a number of wide-ranging factors, for example, economic indicators, expansion of supervisory and governing framework, possibilities and support for investments, commitment of the governmental and other authorities to provide help and support, scientific and technological progresses, development and regulation of financial and capital market products. As mentioned in the field of investment and green financing, one of the most important green financial instruments is green bonds. Green bonds appeared in current years as a response to the severe need to assemble capital to reinforce the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Hence, nations are proceeding towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient future, and, as a result, there is a growing need for financing solutions. Green bonds are supposed to generate and transfer capital from capital markets for various projects, including climate change mitigation and adaptation, renewable energy projects, and others [48][29]. Green bonds are built like traditional bonds—fixed-income debt instruments. An additional tendency in the market is the speeding up of sovereign green bond issuances as governments wish to advance sustainable policies and fulfil their national sustainability agendas [49,50,51][30][31][32]. The success of a green bond issue is determined by the issuer’s reputation, sufficiently good credit rating and environmental, social and governance performance [52][33]. The authors summarized the main benefits of the development of green finance and the issue of green bonds in Table 21.Table 21.

Benefits of the development of green finance and the release of green bonds.

| Issue | Benefit | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Society (solve issues related to the environment) | Lower carbon emissions | Sangiorgi and Schopohl [24], Gianfrate and Peri [53][34], Fatica et al. [54][35], Al Mamun et al. [55][36], Huang and Zhang [56][37], Chang et al. [57][38], Koval et al. [58][39], Koziol at al. [59][40], Umar and Safi [60][41] |

| Fosters renewable energy production, utilization | Anton and Nucu [20], Huang et al. [22], Cheng et al. [61][42], Wang and Taghizadeh-Hersay [62][43] | |

| Regional development | Hou et al. [18], Huang and Zhang [56][37], Mejia-Escobar et al. [63][44] | |

| Issuers | Access to capital at lower costs | Teti et al. [64][45] |

| Stimulate technological innovations | Madaleno et al. [9] | |

| Stimulate financial performance | Du et al. [65][46] |

Table 32.

Challenges for green finance and green bond development.

| Issue | Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Market | Macroeconomic environment | Anh Tu et al. [80][61], Torvanger et al. [81][62] |

| Investors | ||

| Diversification of investments | ||

| Liaw | [ | 7], Orzechowski and Bombol [23], Sangiorgi and Schopohl [24], Bužinskė and Stankevičienė [52][33], Gianfrate and Peri [53][34], Ferrer et al. [66][47], Hadaś-Dyduch et al. [67][48], Chopra and Mehta [68][49] |

3. Challenges of Green Finance

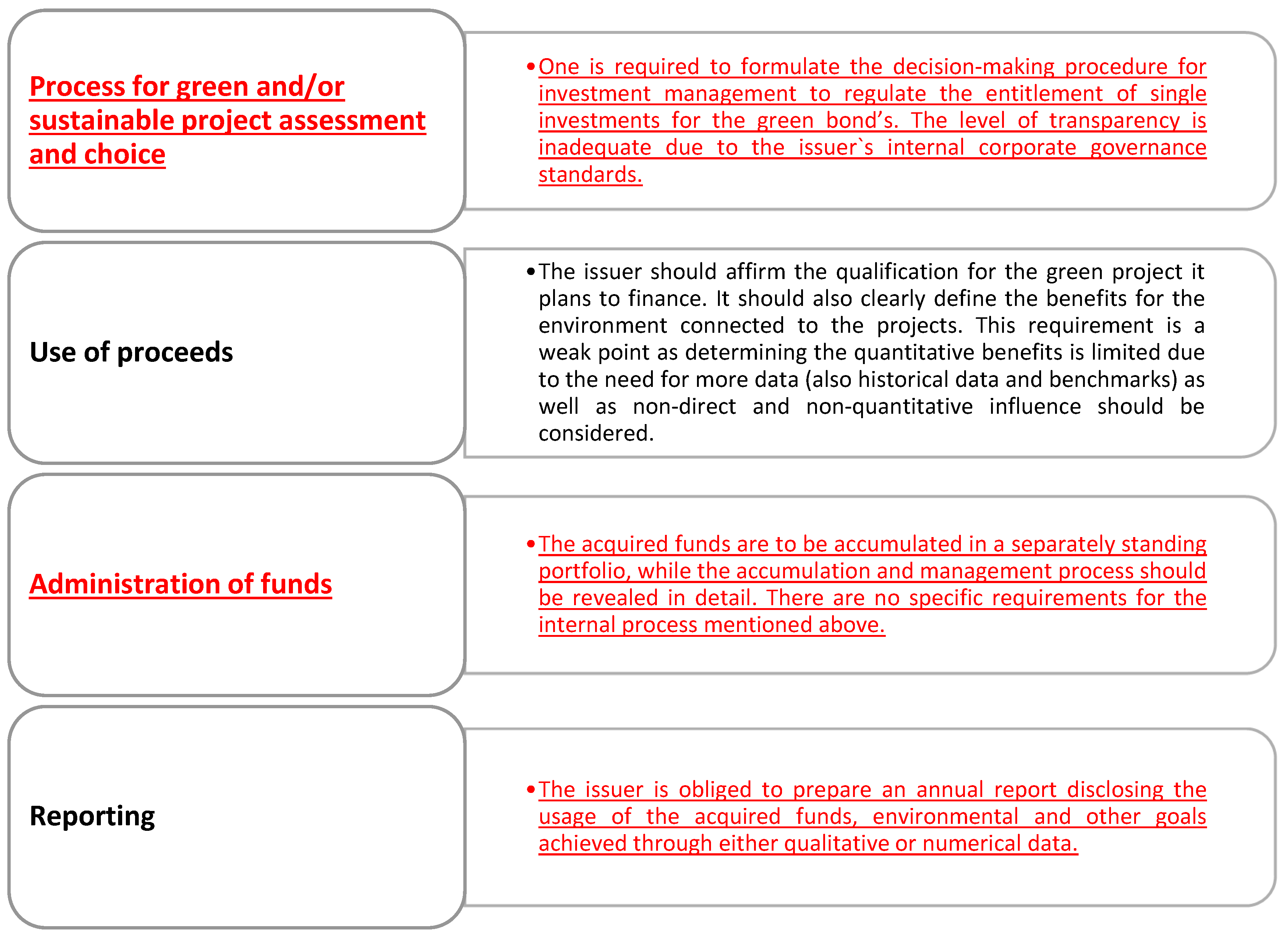

Green bonds are an essential element in achieving sustainability goals. Nevertheless, there are no common rules or standards for green bonds, bringing to life the discussion about greenwashing. The European Union (EU) Commission’s action plan on funding sustainable growth includes the framework of an EU green bond standard, methodologies for low-carbon indices, and metrics for climate-related disclosure [48][29]. In addition, the International Capital Market Association’s Green Bond Principles [78][59] and the Climate Bonds Initiative’s Climate Bond Standards [79][60] clarify whether a bond qualifies as green. As shown in Figure 31, there are four main principles that define a bond as green. Nevertheless, no specific legal requirements for issuing green bonds exist, which would hinder the transparency and market participants’ interest in such a product. Further, the authors summarize the challenges for green finance and green bonds development by splitting them into four different groups: market-, issue-, investor-, and law-related ones.

| , Ejaz et al. | ||

| [ | 82 | ][63], Doğan et al. [83][64] |

| General bond market development | Du et al. [65][46], Deschryver and De Mariz [76][57], Elsayed et al. [77][58], Torvanger et al. [81][62], Ge et al. [84][65] | |

| Greenwashing | Bužinskė and Stankevičienė [52][33], Deschryver and De Mariz [76][57] | |

| Issuers | Costs of meeting requirements | Deschryver and De Mariz [76][57], Alsmadi et al. [85][66] |

| Investors | Insufficient financial and economic benefits | Maltais and Nykvist [3], Bužinskė and Stankevičienė [52][33], Wu (2022) [87][68] |

| Lack of labelled green bond | Li et al. [75][56], Deschryver and De Mariz [76][57] | |

| Lack of green bond project impact information | Deschryver and De Mariz [76][57], Jankovic et al. [88][69] | |

| Law | Lack of regulation | Peng et al. [73][54], Pyka (2023) [86][67] |

References

- United Nations Climate Change. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Schumacher, K.; Chenet, H.; Volz, U. Sustainable finance in Japan. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020, 10, 213–246.

- Maltais, A.; Nykvist, B. Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing sustainability. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020, 1–20.

- Maria, M.R.; Ballini, R.; Souza, R.F. Evolution of Green Finance: A Bibliometric Analysis through Complex Networks and Machine Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 967.

- Mohanty, S.; Nanda, S.S.; Soubhari, T.; Biswal, S.; Patnaik, S. Emerging research trends in green finance: A bibliometric overview. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 108.

- Cortellini, G.; Panetta, I.C. Green bond: A systematic literature review for future research agendas. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 589.

- Liaw, K.T. Survey of green bond pricing and investment performance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 193.

- MacAskill, S.; Roca, E.; Liu, B.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O. Is there a green premium in the green bond market? Systematic literature review revealing premium determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124491.

- Madaleno, M.; Dogan, E.; Taskin, D. A step forward on sustainability: The nexus of environmental responsibility, green technology, clean energy and green finance. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105945.

- Naz, F.; Oláh, J.; Vasile, D.; Magda, R. Green purchase behavior of university students in Hungary: An empirical study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10077.

- Hu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, L. Green Bond Pricing and Optimization Based on Carbon Emission Trading and Subsidies: From the Perspective of Externalities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8422.

- He, N.; Zeng, S.; Jin, G. Achieving synergy between carbon mitigation and pollution reduction: Does green finance matter? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118356.

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. Influence of digital finance and green technology innovation on China’s carbon emission efficiency: Empirical analysis based on spatial metrology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156463.

- Yu, L.; Zhao, D.; Xue, Z.; Gao, Y. Research on the use of digital finance and the adoption of green control techniques by family farms in China. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101323.

- European Environment Agency. Economic Losses from Climate-Related Extremes in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/economic-losses-from-climate-related (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Zhang, D.; Mohsin, M.; Rasheed, A.K.; Chang, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Public spending and green economic growth in BRI region: Mediating role of green finance. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112256.

- Arefjevs, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Natrins, A.; Verdenhofs, A.; Mavlutova, I.; Volkova, T. Financial sector evolution and competencies development in the context of information and communication technologies. Res. Rural Dev. 2020, 35, 260–267.

- Hou, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Green finance drives renewable energy development: Empirical evidence from 53 countries worldwide. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 80573–80590.

- Jin, C.; Lv, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, K. Green finance, renewable energy and carbon neutrality in OECD countries. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 279–284.

- Anton, S.G.; Nucu, A.E.A. The effect of financial development on renewable energy consumption. A panel data approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 330–338.

- Mavlutova, I.; Volkova, T.; Natrins, A.; Spilbergs, A.; Arefjevs, I.; Miahkykh, I. Financial sector transformation in the era of digitalization. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2020, 38.

- Huang, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y. Is there any recovery power for economic growth from green finance? Evidence from OECD member countries. Econ. Change Restruct. 2022, 63, 69.

- Orzechowski, A.; Bombol, M. Energy Security, Sustainable Development and the Green Bond Market. Energies 2022, 15, 6218.

- Sangiorgi, I.; Schopohl, L. Why do institutional investors buy green bonds: Evidence from a survey of European asset managers. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 75, 101738.

- Mavlutova, I.; Fomins, A.; Spilbergs, A.; Atstaja, D.; Brizga, J. Opportunities to increase financial well-being by investing in environmental, social and governance with respect to improving financial literacy under COVID-19: The case of Latvia. Sustainability 2021, 14, 339.

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Managi, S. A bibliometric analysis on green finance: Current status, development, and future directions. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 29, 425–430.

- International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group. Green Finance: A Bot-Tom-Up Approach to Track Existing Flows. 2016. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/financial/gcf/ifc-greentracking.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Bhatnagar, S.; Sharma, D. Evolution of green finance and its enablers: A bibliometric analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112405.

- European Commission. European Green Bond Standard. 2023. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/european-green-bond-standard_en (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Doronzo, R.; Siracusa, V.; Antonelli, S. Green bonds: The sovereign issuers’ perspective. Bank Italy Mark. Infrastruct. Paym. Syst. Work. Pap. 2021.

- Tsonkova, V.D. The Sovereign Green Bonds Market in the European Union: Analysis and Good Practices. Knowl.-Int. J. 2019, 30, 165–172.

- Chesini, G. Sovereign Green Bonds in Europe: Are They Effective in Supporting the Green Transition? In New Challenges for the Banking Industry: Searching for Balance between Corporate Governance, Sustainability and Innovation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 185–212.

- Bužinskė, J.; Stankevičienė, J. Analysis of success factors, benefits, and challenges of issuing green bonds in Lithuania. Economies 2023, 11, 143.

- Gianfrate, G.; Peri, M. The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 127–135.

- Fatica, S.; Panzica, R. Green bonds as a tool against climate change? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2688–2701.

- Al Mamun, M.; Boubaker, S.; Nguyen, D.K. Green finance and decarbonization: Evidence from around the world. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102807.

- Huang, H.; Zhang, J. Research on the environmental effect of green finance policy based on the analysis of pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3754.

- Chang, L.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Chen, H.; Mohsin, M. Do green bonds have environmental benefits? Energy Econ. 2022, 115, 106356.

- Koval, V.; Laktionova, O.; Atstaja, D.; Grasis, J.; Lomachynska, I.; Shchur, R. Green Financial Instruments of Cleaner Production Technologies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10536.

- Koziol, C.; Proelss, J.; Roßmann, P.; Schweizer, D. The price of being green. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103285.

- Umar, M.; Safi, A. Do green finance and innovation matter for environmental protection? A case of OECD economies. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106560.

- Cheng, Z.; Kai, Z.; Zhu, S. Does green finance regulation improve renewable energy utilization? Evidence from energy consumption efficiency. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 63–75.

- Wang, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Green bonds markets and renewable energy development: Policy integration for achieving carbon neutrality. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106725.

- Mejía-Escobar, J.C.; González-Ruiz, J.D.; Franco-Sepúlveda, G. Current state and development of green bonds market in the Latin America and the Caribbean. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10872.

- Teti, E.; Baraglia, I.; Dallocchio, M.; Mariani, G. The green bonds: Empirical evidence and implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132784.

- Du, M.; Zhang, R.; Chai, S.; Li, Q.; Sun, R.; Chu, W. Can green finance policies stimulate technological innovation and financial performance? Evidence from Chinese listed green enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9287.

- Ferrer, R.; Shahzad, S.J.H.; Soriano, P. Are green bonds a different asset class? Evidence from time-frequency connectedness analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125988.

- Hadaś-Dyduch, M.; Puszer, B.; Czech, M.; Cichy, J. Green Bonds as an Instrument for Financing Ecological Investments in the V4 Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12188.

- Chopra, M.; Mehta, C. Going green: Do green bonds act as a hedge and safe haven for stock sector risk? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103357.

- The City UK. Green Finance: A Quantitative Assessment of Market Trends. 2022. Available online: https://www.thecityuk.com/media/l0lhnctn/green-finance-a-quantitative-assessment-of-market-trends-1.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Climate Bond Initiative. Sustainable Debt Global State of the Market. 2022. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_sotm_2022_03e.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Association for Financial Markets in Europe. ESG Finance Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.afme.eu/portals/0/dispatchfeaturedimages/afme%20sustainable%20finance%20report%20-%20q1%202022.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Alharbi, S.S.; Al Mamun, M.; Boubaker, S.; Rizvi, S.K.A. Green finance and renewable energy: A worldwide evidence. Energy Econ. 2023, 118, 106499.

- Peng, W.; Lu, S.; Lu, W. Green financing for the establishment of renewable resources under carbon emission regulation. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1210–1225.

- Zhang, Y.; Umair, M. Examining the interconnectedness of green finance: An analysis of dynamic spillover effects among green bonds, renewable energy, and carbon markets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 77605–77621.

- Li, Z.; Kuo, T.H.; Siao-Yun, W.; Vinh, L.T. Role of green finance, volatility and risk in promoting the investments in Renewable Energy Resources in the post-COVID-19. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102563.

- Deschryver, P.; De Mariz, F. What future for the green bond market? How can policy-makers, companies, and investors unlock the potential of the green bond market? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 61.

- Elsayed, A.H.; Naifar, N.; Nasreen, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Dependence structure and dynamic connectedness between green bonds and financial markets: Fresh insights from time-frequency analysis before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105842.

- International Capital Market Association. Green Bond Principles. 2021. Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks/green-bond-principles-gbp/ (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Climate Bonds Initiative. Climate Bond Standards. 2023. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/climate-bonds-standard-v4 (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Anh Tu, C.; Sarker, T.; Rasoulinezhad, E. Factors influencing the green bond market expansion: Evidence from a multi-dimensional analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 126.

- Torvanger, A.; Maltais, A.; Marginean, I. Green bonds in Sweden and Norway: What are the success factors? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129177.

- Ejaz, R.; Ashraf, S.; Hassan, A.; Gupta, A. An empirical investigation of market risk, dependence structure, and portfolio management between green bonds and international financial markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132666.

- Doğan, B.; Trabelsi, N.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ghosh, S. Dynamic dependence and causality between crude oil, green bonds, commodities, geopolitical risks, and policy uncertainty. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 89, 36–62.

- Ge, P.; Liu, T.; Huang, X. The effects and drivers of green financial reform in promoting environmentally-biased technological progress. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117915.

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Alrawashdeh, N.; Al-Gasaymeh, A.; Moh’d Al-hazimeh, A.; Zakari, A. A bibliometric analysis of green bonds and sustainable green energy: Evidence from the last fifteen years (2007–2022). Sustainability 2023, 15, 5778.

- Pyka, M. The EU Green Bond Standard: A Plausible Response to the Deficiencies of the EU Green Bond Market? Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2023, 24, 623–643.

- Wu, Y. Are green bonds priced lower than their conventional peers? Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2022, 52, 100909.

- Jankovic, I.; Vasic, V.; Kovacevic, V. Does transparency matter? Evidence from panel analysis of the EU government green bonds. Energy Econ. 2022, 114, 106325.

- Menke, R.; Abraham, E.; Parpas, P.; Stoianov, I. Demonstrating demand response from water distribution system through pump scheduling. Appl. Energy 2016, 170, 377–387.

- Mohsin, M.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Panthamit, N.; Anwar, S.; Abbas, Q.; Vo, X.V. Developing low carbon finance index: Evidence from developed and developing economies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101520.

- Yang, C.; Masron, T.A. Impact of digital finance on energy efficiency in the context of green sustainable development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11250.

- Puschmann, T.; Hoffmann, C.H.; Khmarskyi, V. How green FinTech can alleviate the impact of climate change—The case of Switzerland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10691.

- Mavlutova, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Verdenhofs, A.; Natrins, A.; Arefjevs, I.; Volkova, T. Digital transformation as a driver of the financial sector sustainable development: An impact on financial inclusion and operational efficiency. Sustainability 2022, 15, 207.

- Zeng, S.; Tanveer, A.; Fu, X.; Gu, Y.; Irfan, M. Modeling the influence of critical factors on the adoption of green energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112817.

- Shehzad, A.; Qureshi, S.F.; Saeed, M.Z.; Ali, S. The impact of financial risk attitude on objective-oriented investment behavior. Int. J. Financ. Eng. 2023, 10, 2250022.

- Gilchrist, D.; Yu, J.; Zhong, R. The limits of green finance: A survey of literature in the context of green bonds and green loans. Sustainability 2021, 13, 478.

More