2. Osteoporosis Pathophysiology

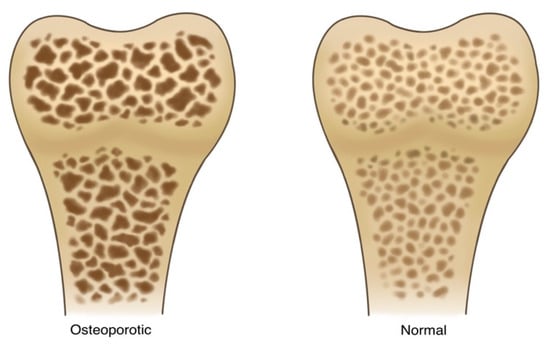

Osteoporosis is a disorder characterized by decreased bone mass, density, quality, and strength, as shown in

Figure 1. It is caused by imbalances in the process of bone remodeling to favor MSC senescence—and a shift in differentiation potential to favor adipogenesis over osteogenesis. In this pathological state, bone loses its structural integrity and becomes more susceptible to fractures

[7][13]. This imbalance is primarily linked to variations in the activity levels of osteoclasts and osteoblasts.

Figure 1. A side-by-side illustration depicting the stark contrast between normal and osteoporotic bone. The normal bone structure (right) is well defined, demonstrates a thick trabecular architecture within the bone matrix, demonstrates sufficient mineralization and calcium content, and, finally, shows minimal signs of fractures of degradation. The osteoporotic bone (left) shows signs of advanced bone loss and weakening. There is a dramatic reduction in trabecular density and thickness, resulting in a porous and fragile appearance. The pronounced gaps and voids within the bone matrix represent areas of compromised strength.

Osteoporosis can be classified into two major groups: primary and secondary osteoporosis. Primary osteoporosis includes conditions for which there is no underlying medical etiology. These include idiopathic and involutional osteoporosis. Idiopathic osteoporosis occurs mostly in children and young adults and continues to have no known etiopathogenesis

[6][8][6,14]. Involutional osteoporosis affects both men and women and is known to be closely related to aging and hormonal imbalances. Involutional osteoporosis can be further classified into Type I and Type II. Type I involutional osteoporosis mostly affects postmenopausal women and is often referred to as “postmenopausal osteoporosis”. This condition affects women between 51 and 71 years of age and is characterized by rapid bone loss

[6][8][6,14]. Type II involutional osteoporosis—often referred to as “senile osteoporosis”—mostly affects those above 75 years of age. This condition is characterized by a primarily trabecular and cortical pattern of bone loss

[6][8][6,14]. Secondary osteoporosis occurs due to an underlying disease or medication use, and it accounts for less than 5% of all cases of osteoporosis

[6][8][6,14].

Traditional pathophysiological models of osteoporosis have emphasized the endocrine etiology of the condition. Estrogen deficiencies and the resultant secondary hyperparathyroidism, as described by models, coupled with an inadequate vitamin D and calcium intake, have been touted as the key determinants in the development of osteoporosis

[9][15]. The postmenopausal cessation of ovarian function and subsequent decreases in estrogen levels have been known for decades to be key events in the acceleration of bone loss. The effects of estrogen loss are mediated by the direct modulation of osteogenic cellular lineages via the estrogen receptors on these cells. Specifically, decreased estrogen leads to simultaneous increases and decreases in osteoclast and osteoblast activities, respectively, leading to metabolic imbalances favoring bone resorption. Similarly, it is known that nutritional imbalances, specifically in vitamin D and calcium, can also promote bone resorption

[9][10][15,16].

However, emerging research on bone homeostasis suggests that the pathophysiological mechanisms of osteoporosis extend beyond this unilateral endocrine model

[9][15]. Rather, more dynamic models are being explored as the pathophysiological drivers behind the disease.

An important discussion point is the use of animal models for osteoporosis. Because of the similarity in pathophysiologic responses between the human and rat skeleton, the rat is a valuable model for osteoporosis. Rats are safe to handle, accessible to experimental centers, and have low costs of acquisition and maintenance

[11][17]. Through hormonal interventions, such as ovariectomy, orchidectomy, hypophysectomy, and parathyroidectomy), and immobilization and dietary manipulations, the laboratory rat has provided an aid to the development and understanding of the pathophysiology of osteoporosis

[11][17].

2.1. Osteoimmunological Model

The osteoimmunological model is a relatively novel one that capitalizes on the interplay between the immune system and the skeletal system

[9][15]. It has become increasingly clear that the immune and skeletal systems share multiple overlapping transcription factors, signaling factors, cytokines, and chemokines

[9][15].

Osteoclasts were the first cells in the skeletal system discovered to serve immune functions

[9][15]. Some of the first insights into osteoimmunological crosstalk were gained by Horton et al. (1972), who explored the interactions between immune cells and osteoclasts leading to musculoskeletal inflammatory diseases

[12][18]. The authors found that, in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis, the stimulation of bone resorption by osteoclasts is exclusively mediated by Th17 cells, which produce IL-17 to stimulate RANKL expression

[9][12][13][15,18,19].

The osteoimmunological pathophysiological framework for osteoporosis is further strengthened by studies conducted by Zhao et al. (2016), who showed that osteoporotic postmenopausal women express increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1, IL-6, or IL-17) when compared to their non-osteoporotic counterparts

[14][20]. Cline-Smith et al. (2020) further strengthened this model by demonstrating a relationship between the loss of estrogen and the promotion of low-grade T-cell-regulated inflammation

[15][21]. Regulatory T cells (T

reg) have also been found to have anti-osteoclastogenic effects within bone biology through the expression of the transcription factor FOXP3

[16][22]. Accordingly, Zaiss et al. (2010) found that the transfer of T

reg cells into T-cell-deficient mice was associated with increased bone mass and decreased osteoclast expression

[9][16][15,22].

B cells also play a role in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Panach et al. (2017) showed that B cells produce small amounts of both RANKL and OPG and modulate the RANK/RANKL/OPG axis

[9][17][18][15,23,24].

2.2. Gut Microbiome Model

Another rapidly expanding model for the pathophysiology of osteoporosis explores the influence of the gut microbiome (GM) on bone health. It is now widely accepted that the GM influences the development and homeostasis of both the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and extra-GI tissues. GM health also affects nutrient production, host growth, and immune homeostasis

[19][20][21][25,26,27]. Moreover, complex diseases, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), transient ischemic attacks, and rheumatoid arthritis, have all been linked to changes in the GM

[19][20][21][25,26,27].

Ding et al. (2019) showed that germ-free mice exhibit increased bone mass, suggesting that a correlation exists between bone homeostasis and the GM

[20][26]. This correlation was also redemonstrated by Behera et al. (2020)’s findings that the modulation of the GM through probiotics and antibiotics affects bone health

[19][20][25,26]. Though the relationship between the GM and bone health is still being explored, various mechanisms have been proposed to explain this close “microbiota–skeletal” axis

[9][15].

One such mechanism stems from the relationship between the GM and metabolism. The GM has been shown to influence the absorption of nutrients required for skeletal development (i.e., calcium), thereby affecting bone mineral density

[22][28]. Additionally, nutrient absorption is thought to be influenced by GI acidity, which is directly regulated by the GM

[9][15]. Moreover, the microbial fermentation of dietary fiber to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) also plays an important role in the regulation of nutrient absorption in the GI tract. Whisner et al. (2016) and Zaiss et al. (2019) recently reported that the consumption of different prebiotic diets (that can be fermented to SCFAs) was associated with an increased GI absorption of dietary calcium

[23][24][29,30]. Beyond their influence on the GI tract, SCFAs have emerged as potent regulators of osteoclast activity and bone metabolism

[25][31]. SCFAs have protective effects against the loss of bone mass by inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption

[9][26][15,32]. SCFAs are amongst the first examples of gut-derived microbial metabolites that diffuse into systemic circulation to affect bone homeostasis

[9][15].

The GM also modulates immune functions. It is believed that the GM’s effect on intestinal and systemic immune responses, which, in turn, modulate bone homeostasis as described above, is yet another link between the GM and the skeletal system. Bone-active cytokines are released directly by immune cells in the gut, absorbed, and then circulate to the bone; these cytokines play a pivotal role in the GM–immune–bone axis

[9][21][15,27].

Finally, it is understood that the bone-forming effect of intermittent PTH signaling closely depends on SCFAs—specifically, butyrate, a product of the GM. Li et al. (2020) provided evidence for butyrate acting in concert with PTH to induce CD4+ T cells to differentiate into T

reg cells. Differentiated T

reg cells then stimulate the Wnt pathway, which is pivotal for bone formation and osteoblast differentiation, as discussed above

[9][27][15,33]. Interventions that focus on probiotics and targeting the GM and its metabolic byproducts may be a potential future avenue for preventing and treating osteoporosis.

2.3. Cellular Senescence Model

Cellular senescence describes a cellular state induced by various stressors, characterized by irreversible cell cycle arrest and resistance to apoptosis

[28][34]. Senescent cells produce excessive proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix-degrading proteins, known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) proteins

[29][35]. The number of senescent cells increases with aging and has been linked to the development of age-related diseases, such as DM, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and osteoporosis

[30][36].

Farr et al. (2016) explains the role of cellular senescence in the development of osteoporosis

[31][37]. These authors found that there is an accumulation of senescent B cells, T cells, myeloid cells, osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts, and osteocytes in bone biopsy samples from older, postmenopausal women compared to their younger, premenopausal counterparts, suggesting that these cells become senescent with age

[31][37]. Further studies conducted by Farr et al. (2017) suggest a causal link between cellular senescence and age-related bone loss by showing that the elimination of senescent cells or the inhibition of their produced SASPs had a protective and preventative effect on age-related bone loss

[32][38]. These findings suggest that targeting cellular senescence through “senolytic” and “senostatic” interventions may have good results.

2.4. Genetic Component of Osteoporosis

Bone mineral density has up to 80% of variance in twin studies and is a heritable trait. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in specific genes, in addition to polygenic and multiple gene variants, have been identified

[33][39]. Makitie et al. summarized up to 144 different genes that have been reported to be linked to variances in bone mineral density

[33][39]. As an example, Zheng et al. showed that rs11692564 had an effect of +0.20 SD for lumbar spine BMD

[34][40]. It is well known that the WNT pathway plays a role in bone homeostasis, as it promotes bone cell development, differentiation, and proliferation

[35][41]. Dysregulation in its signaling pathway leads to changes in bone mass, such as osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome, Pyle’s disease, and van Buchem disease

[33][39]. PLS3 is another recently identified gene that is linked to early-onset osteoporosis. PLS3 functions by altering osteocyte function through an abnormal cytoskeletal microarchitecture and bone mineralization

[36][37][42,43]. Finally, there are several genes that have a known effect on changes in the bone extracellular matrix. COL1A1 and COL1A2 mutations are associated with osteogenesis imperfecta; XYLT2 leads to spondyloocular syndrome; and FKBP10 and PLOD2 mutations lead to Bruck syndrome 1 and 2, respectively

[38][39][44,45].