Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Dinesh Shah and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

A flexible and dependable method that has been extensively employed to construct nanofibrous scaffolds that resemble the extracellular matrix made from polymeric materials is electrospinning (ES). ES is superior to other techniques because of its unique capacity to create nanofibers with a high surface-to-volume ratio, low cost, simplicity of setup, freedom in material choice, and ability to alter the surface attributes and usefulness of the nanofibers.

- green solvents

- tissue engineering

- essential oils

- volatile organic compounds

1. Biomimetic from Extracellular CMatrix and Polymeric Nanofibers

Biomimetics or biomimicry is the practice of imitating models, systems, and elements from nature to solve complex human problems. It involves drawing inspiration from natural selection solutions found in nature and applying those principles to human engineering [1][51]. Living organisms have developed specialized structures and materials through natural selection over millions of years. Biomimetics has facilitated the creation of innovative technologies that draw inspiration from biological solutions found at both macro and nanoscales. Nature has found solutions to engineering challenges such as self-healing, tolerance to environmental exposure, resistance, hydrophobicity, and self-assembly [2][3][52,53]. Designs inspired by biomimicry will ultimately enable human productions to be more efficient, resilient, and sustainable. Biomimicry has applications in various sectors of human activity, including medicine, research, industry, economy, architecture, urban planning, agriculture, and management. It can be directly or indirectly applied to all sectors. Some biomimetic processes have been in use for years, such as the artificial synthesis of certain vitamins and antibiotics. More recently, biomimetics have been proposed for use in electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds that mimic important characteristics of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). This provides a promising strategy for restoring functions and achieving positive outcomes in tissue regeneration [4][5][54,55].

Nanofibers in cellular scaffolds imitate the structure of native extracellular matrix (ECM) elements found in diverse tissues and organs such as bone, cartilage, tendon, and skin. This biomimetic approach is based on the principle of mimicking the natural fibrous organization of tissues at the nanoscale level [6][56]. The nanofibrous scaffold can provide cues to cells, promoting their growth and facilitating the synthesis of authentic extracellular matrices. The electrospun nanofibrous scaffold plays a pivotal role in determining the mechanical properties of tissue scaffold. The nanoscale structures of the scaffold enable interactions with cells, allowing for them to actively engage with the matrix, leading to functionalization, remodelling, and resembling the natural cellular remodelling process within the ECM [7][8][57,58]. Continuous efforts are being made to develop biomimetic scaffolds that provide structural support for cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. These scaffolds are also employed for bringing bioactive molecules, such as growth factors and signalling cues, to support tissue regeneration and enhance cellular responses.

The objective of tissue engineering is to replicate the ECM, which is composed of a variety of proteins like collagen, laminin, and fibronectin that act as cell-binding ligands. In order to encourage cell adhesion between cellular frameworks and the surrounding environment of the ECM, integrin-recognizing peptide sequences are essential [9][10][59,60]. Traditional synthetic biodegradable aliphatic polyesters like PLA, PLGA, and PCL continue to be the ideal materials to produce biomimicking nanofibrous scaffolds owing to their exceptional processability, biocompatibility, and mechanical performance. These synthetic polymeric nanofibers have effectively replicated the physical dimensions and morphology of collagen, which serves as a key constituent of the native extracellular matrix (ECM) and the primary structural protein in the human body. Consequently, significant efforts have been made to create collagen-based scaffolds that can closely mimic the natural environment [11][61].

Various scaffolds have been developed successfully to imitate the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the interstitial ECM. However, limited progress has been made in reproducing the two-dimensional (2D) basement membrane (BM) of the ECM. These membranes play a crucial role in establishing the functional polarization of epithelial and endothelial cell layers throughout the body and are essential for artificial organ technologies [12][13][62,63]. Synthetic polymeric nanofibrous scaffolds hold the potential to act as an outstanding biomimetic platform for systematically studying cell–matrix interactions. Biomimetic nanofibrous scaffolds provide a platform for studying cell–matrix interactions and contribute to the design and fabrication of future biomimetic scaffolds in a precise and rational manner.

2. Electrospinning Process and Membrane Morphology

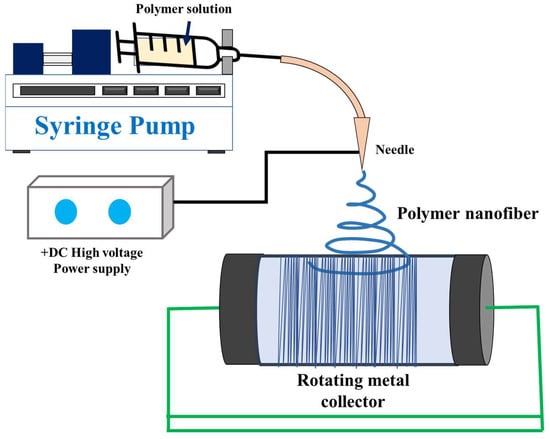

Electrospinning has gained recognition for its ability to create scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), making it a valuable addition to conventional scaffold-production techniques such as gas foaming, solvent-casting, fibre bonding, freeze-drying, particulate leaching, etc., [14][15][66,67]. Electrospinning is a highly versatile and cost-effective process that produces long, continuous fibres with diameters ranging from 10 nanometres to some micrometres, achieved by applying high electrical voltage [16][17][18][68,69,70]. A typical electrospinning setup as depicted in Figure 1 comprises four main components: a high voltage source, a spinneret (typically a hollow metal needle), a collector (grounded or negatively biased), and a syringe pump [19][20][21][71,72,73]. The syringe pump is employed to propel a polymer solution or melt through the spinneret. As the polymer liquid (solution or melt) is subjected to a high electrical potential, electric charges build up on the face of the liquid drop at the tip of the needle [19][22][23][71,74,75].

Figure 1.

Schematic setup of simple electrospinning machine.

Table 1.

Effect of parameters on morphology of nanofibrous membranes.

| Parameters | Effect on Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|

| Solution (material) parameters | |

| Solvent vapor pressure | Increased porosity is associated with greater volatility [31][83]. |

| Polymeric concentration | Higher concentrations (within the optimal range) lead to an increase in fiber diameter [32][84]. |

| Solvent choice | The choice of solvent is crucial, as it can significantly affect the solubility and rheological properties of the spinning solution. Different solvents can lead to variations in fiber diameter and morphology [33][85]. |

| Solution viscosity | Higher viscosity (within the optimal range) results in an increase in fiber diameter. However, exceeding the critical viscosity value can lead to the formation of beaded or deformed nanofibers, and may even cause clogging of the spinneret [34][86]. |

| Solution surface tension | The surface tension of the spinning solution affects the ability of the solution to form a stable jet. A lower surface tension promotes the formation of thinner fibers, while a higher surface tension results in thicker fibers. Surfactants are sometimes added to adjust the surface tension and improve fiber formation [35][87]. |

| Solution conductivity | Increasing the conductivity leads to a decrease in fiber diameter, and higher conductivity can result in more pronounced bending instabilities, leading to the formation of non-uniform or beaded fibers [36][88]. |

| Processing (Operational) parameters | |

| Voltage | There is no definitive correlation between fiber diameter and voltage; however, it is commonly observed that increases in applied voltage cause a reduction in fiber diameter. Additionally, higher voltages may result in a higher probability of bead formation [37][89]. |

| Flow rate | Enhancement of the fiber diameter and the occurrence of bead formation are commonly observed at higher feed rates (above the minimum rate) [38][90]. |

| Needle-collector distance | Within the optimal range, the fiber diameter tends to decrease as the spinneret to the collector distances increases [39][91]. |

| Ambient (Environmental) parameters | |

| Temperature | Increasing the temperature generally leads to a decrease in fiber diameter [40][92]. |

| Humidity | Higher humidity levels tend to induce the formation of circular pores in the fibers [41][93]. |

3. Recent Advancement of Electrospinning

3.1. Advancement in Electrospinning Machine

In addition to the traditional electrospinning technique, various modifications of this method have been recently developed. These include co-electrospinning or co-axial electrospinning, multi-needle, and needleless electrospinning. The multi-needle and needleless electrospinning techniques are employed to improve the productivity of the conventional electrospinning process [42][112]. On the other hand, co-axial electrospinning has been developed to produce core–shell and multilayer composite nanofibrous structures, offering improved functionalities and superior quality compared to conventional electrospinning methods. In co-axial electrospinning, two separate nanofiber components are fed through different coaxial capillary channels and combined to form core–shell composite nanofibers [43][113].

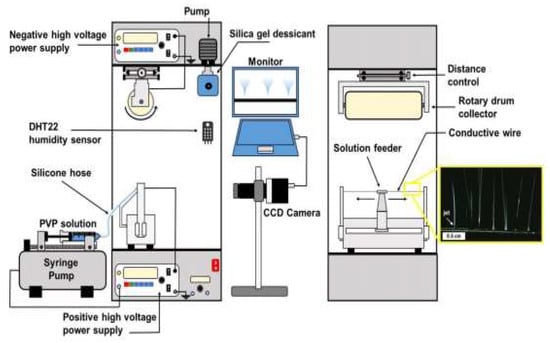

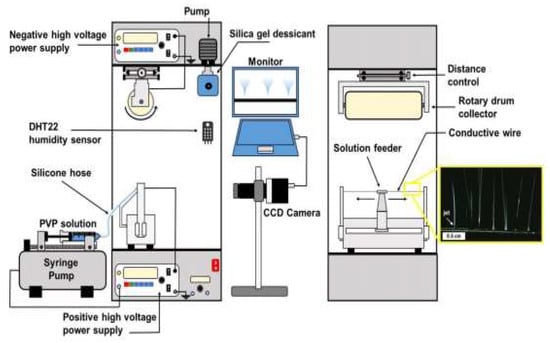

The introduction of co-axial electrospinning has played an important role in the comprehensive production of various functional nanomaterials. For instance, co-axial electrospinning has enabled the efficient production of two-layer core–shell polymer nanofibers. Co-electrospinning, on the other hand, is commonly employed to fabricate single-layer and bilayer nanofibers. However, these nanofiber structures have limitations in terms of assembly configurations and functionalities [44][45][114,115]. By increasing the number of nanofiber layers, the connectivity and functionalities of composite materials can be improved. Recent research has demonstrated the fabrication of multifunctional nanofibers with more than two layers using co-electrospinning. Additionally, the needleless electrospinning system has been widely adopted by researchers to increase fibre productivity [46][116]. This system utilizes two high voltage sources, one connected to the rotary drum collector and the other to the conductive wire, as illustrated in Figure 2.

3.2. Post-Electrospinning Process for Membrane Modification

Although the electrospinning setup is simple, the production of fibres is complex and requires careful consideration of multiple parameters for optimization. Electrospun nanofiber membranes can be tailored to achieve the desired morphology, structure, and functionalities by controlling various operational, material, environmental, and post-processing parameters, such as drying temperature and humidity [48][49][117,118]. After the formation of nanofibers on the collector, residual solvents may still be present in the mat.

Therefore, additional post-treatment methods are typically employed to ensure complete drying. The drying process is typically carried out in a dry or vacuum oven at a temperature slightly below the boiling point of the solvent employed [50][119]. This controlled temperature allows for the residual solvent to evaporate slowly without forming pores, which could occur if a higher temperature were used for drying. Maintaining low humidity during the drying process is crucial to prevent moisture from permeating the nanofiber membrane. High humidity could potentially cause phase separation or pore formation within the nanofibers, which should be avoided to preserve their integrity and desired properties [51][52][120,121].

3.3. Replacement of Toxic Organic Solvent by Green Solvent

Electrospinning has traditionally relied on the use of VOCs as solvent to dissolute polymeric materials. The selection of solvents is based on their capacity to dissolve the polymer chains effectively and evaporate rapidly over the short distance between the nozzle and the collector during the electrospinning process. During this process, large amounts of such toxic vapor may degrade the indoor air quality and cause serious health problems for humans. Moreover, in various applications such as tissue engineering, biomedical, and agriculture, the toxicity of these organic solvents is a critical concern [53][54][122,123]. Residual traces of these chemicals can have negative long-term environmental impacts and pose health hazards. For instance, prolonged exposure to toluene is suspected to cause organ damage, while chloroform and DCM are classified as likely carcinogens to humans according to the World Health Organization [55][124].

Similarly, acetonitrile, acids, formaldehyde, tetrahydrofuran, dimethylformamide, tetrafluoroethylene, methylene chloride, dichloroethane, and pyridine have also been connected to bad effects on human health. Additionally, many air fresheners contain five main ingredients: formaldehyde, phthalates, parabens, petroleum distillates, and p-dichlorobenzene, which can pose serious health hazards such as nausea, infertility, neurological dysfunction, leukaemia, and cancer [56][125]. This highlights the necessity for alternative, non-toxic, and environmentally friendly solvents [57][126].