1. Membranous Nephropathy Supportive Therapy

Regardless of the degree of proteinuria, renal function and extent of NS, all patients with

membranous nephropathy (MN

) should receive the best possible supportive care and be treated to prevent possible complications from the disease

[1][7]. Such treatment may reduce both the morbidity and mortality independently of immunosuppressive therapy.

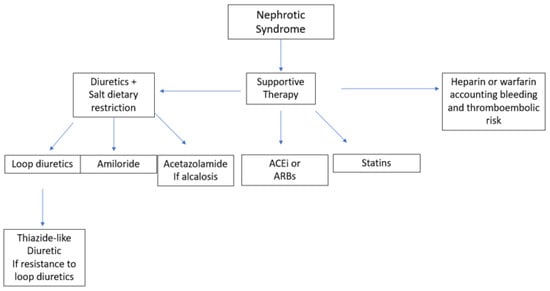

Figure 12 shows different therapeutic options for the symptomatic treatment of nephrotic syndrome.

Figure 12. Different therapeutic options for the symptomatic treatment of MN. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blockers.

The treatment of edema includes both the use of diuretics and dietary salt restriction. Loop diuretics administered twice daily are the first-line therapy

[2][28]. As the prolonged administration of furosemide can lead to adaptation mechanisms, there is some evidence of better results with torsemide and bumetanide

[3][29]. If there is superimposed diuretic resistance, a thiazide-like diuretic such as chlortalidone, hydrochlorothiazide or metolazone can be added to prevent sodium reabsorption in the distal areas of the nephron. While using such a combination of diuretics, administration of a thiazide-like diuretic two to five hours before a loop diuretic can minimize distal sodium reabsorption. The use of amiloride and acetazolamide may help in the management of hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis, respectively. As gastrointestinal absorption of these diuretics may be affected by bowel wall edema, intravenous loop diuretics may be a valid alternative. Intravenous albumin may help to improve the delivery of the diuretic to its target site in the nephron and should be considered if serum albumin levels are below 2.0 g/dL

[4][30]. Daily sodium intake should not exceed 2 g or 88 mEq, while water restriction is not required unless hyponatremia or fluid overload is present

[1][7].

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin-II-receptor blockers (ARBs) are the first-line therapy for blood-pressure control thanks to their additional effect in reducing proteinuria. Reaching the target blood pressure (i.e., systolic blood pressure <120 mmHg) can both protect against cardiovascular risks and slow down the loss of the GFR. On the other hand, loss of renal function can be prevented if proteinuria is reduced to less than 0.5 g per day or slowed to less than 1.5 g per day

[1][7]. In addition, the reduction in proteinuria and subsequent increase in serum protein and albumin levels can prevent infection, metabolic and thromboembolism risk. ACEi and ARBs can reduce proteinuria by up to 50%. These drugs should be given at the maximum tolerated dose and should only be discontinued if there is an increase in creatinine of more than 30%, if there is a continuous loss of renal function, or if the induced hyperkalemia no longer responds to any available drug treatment. If this is the case, a direct renin inhibitor (DRI) or a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) may be used to replace ACEi or ARBs

[5][31] but be an addition to them

[6][32]. Finally, non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers (CCB)

[7][33] may also reduce proteinuria, though only in a minor way.

Hyperlipidemia must be treated if the patient has other risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes, smoking, hypertension or being overweight. The first step in treating lipid abnormalities is diet and lifestyle modification. Statins are effective in lowering lipid levels, and there is some evidence that atorvastatin may also reduce proteinuria

[8][34] compared with rosuvastatin. Currently, there are insufficient data to broadly use second-line therapies such as ezetimibe

[9][35] or PCSK9 inhibitors

[1][7].

Among the different forms of glomerulonephritis, MN is the one that carries the greatest risk of thromboembolic events, especially deep-vein thrombosis and renal-vein thrombosis

[10][36], and the risk is even higher depending on the degree of proteinuria and if albumin levels fall below 2.5 g/L. Full anticoagulation is mandatory if a thromboembolic event has already occurred. On the other hand, prophylactic anticoagulation should be carefully evaluated to account for both the risk of bleeding and thromboembolism

[1][7]. The first-line therapy is heparin (or a derivative thereof) or warfarin; further studies are currently needed to investigate the potential role of direct oral anticoagulants. In patients with an albumin level below 2.5 g/L, a high venous thromboembolism risk and a high bleeding risk that complicates the use of warfarin, aspirin can be used, as it is in patients at risk of arterial thromboembolism

[11][37].

2. History of Immunosuppressive Therapy in Membranous Nephropathy

The first drugs used to treat MN were exclusively glucocorticoids, although trials conducted with prednisone showed no or only transient benefit

[12][13][38,39]. In addition, a trial involving cyclophosphamide failed to show any improvement in proteinuria or renal function

[14][40], and retrospective studies that included chlorambucil raised suspicions that it might be associated with cancer

[15][41].

In 1984, a multicenter Italian RCT assigned 67 patients with MN to symptomatic treatment or to an alternating combination of chlorambucil and glucocorticoids for six months. At months 1, 3 and 5, 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone was administered for 3 days and 0.5 mg/kg oral prednisone for a subsequent 27 days, while chlorambucil at 0.2 mg/kg/day was given at months 2, 4 and 6. The treatment group showed a stabilization of renal function and an improvement in proteinuria, and these results were confirmed 10 years later

[16][42]. This approach, also known as “Protocollo Ponticelli”, was shown to achieve better results than glucocorticoid administration alone

[17][43]. In 1998, results were published from a trial designed to prove the non-inferiority of cyclophosphamide compared to chlorambucil in alternating therapy; patients treated with the former had better rates of complete and partial remission, relapsed less frequently and also seemed to tolerate the drug. Since then, cyclophosphamide has replaced chlorambucil in the approach known as the “Modified Ponticelli”

[18][44].

Early indications of a potential role for cyclosporine in the treatment of MN came from several observational studies in which patients achieved partial or complete remission

[19][20][21][45,46,47]. However, this treatment option was hampered by frequent relapses upon the reduction or withdrawal of the drug and by its potential nephrotoxicity. Subsequently, two randomized studies showed an improvement in slowing the decline of renal function and proteinuria compared with the placebo

[22][48] and better remission rates when combined with prednisone compared with placebo plus prednisone

[23][49]. Similar to cyclosporine, tacrolimus also showed a good response but had a high relapse rate upon discontinuation. These data come from retrospective

[24][50], intervention

[25][51] and randomized studies

[26][52]. When tacrolimus was used in combination with glucocorticoids, better results in terms of remission rates and relapses were obtained with 24 months of therapy compared with 12 months

[27][53]. Another proposed drug was mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), although this had a higher risk of relapse compared with cyclophosphamide

[28][54] and a lower rate of complete–partial remission when combined with glucocorticoids compared with cyclophosphamide

[29][55]. It should be noted that no difference in terms of proteinuria reduction or remission achievement was found between the use of MMF and supportive therapy alone

[30][56].

3. Treatment of Membranous Nephropathy in KDIGO 2021

Since patients suffering from MN can spontaneously experience remission, it is crucial to determine which patient would benefit more from immunosuppressive therapy and who can be treated only with supportive therapy. Hence, the latest KDIGO guidelines

[1][7] suggest assessing the risk of the loss of kidney function by dividing patients into subgroups of low, moderate, high and very-high risk of progression toward end-stage renal disease, accounting for both clinical and laboratory criteria.

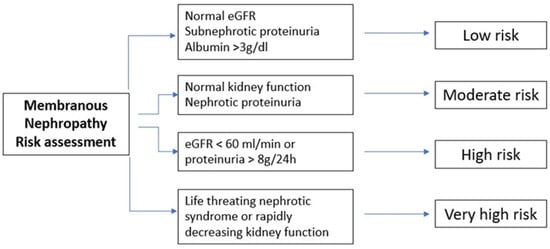

Figure 23 summarizes the four different subgroups with regard to their risk of progression toward end-stage renal disease.

Figure 23. Schematic representation of different subgroups with different risk levels of progression toward end-stage renal disease. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Consequently, it is suggested to wait 6 months while using maximal anti-proteinuria therapy since spontaneous remission can occur. On the other hand, if high-level proteinuria, high-tier PLA2R auto-antibodies or low-molecular-weight proteinuria are present, an earlier re-evaluation is mandatory, while if kidney function is rapidly decreasing and if nephrotic syndrome is unresponsive to symptomatic therapy, an early course of immunosuppressive therapy should be started at soon as possible. The chance of spontaneous remission is higher in patients with proteinuria below 4 g/day compared with those below 8 g/day and 12 g/day (45% vs. 34% vs. 25–40, respectively) and in patients with lower tiers of anti-PLA2R antibodies compared with higher ones. Moreover, in addition to single values, it is fundamental to evaluate the trajectory of such parameters.

Consequently, immunosuppressive therapy should be practiced only in patients at risk of progressive kidney injury. It is not required if proteinuria is not in nephrotic range (i.e., below 3.5 g/day), if serum albumin is greater than 30 g/L and if the eGFR is above 60 mL/min. Such patients usually have low risk of thromboembolic complications and have few or any symptoms and can therefore be managed only with conservative therapy. Immunosuppressive therapy in such patients would add risks without any potential benefits.

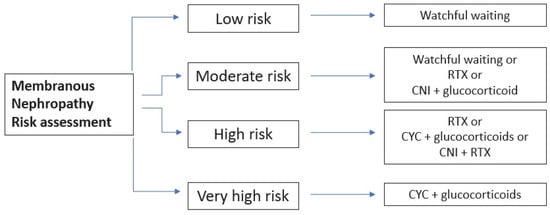

On the other hand, if there is at least one risk factor for disease progression, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. The choice of the specific therapy should account for the patients’ characteristics, drug availability, preference from patients and physicians and the specific side effect of each drug. Figure 34 summarizes the choice of therapies, accounting for the risk category. Different therapeutical protocols are represented in Table 1.

Figure 34. Schematic representation of different subgroups with respective therapy. CYC, cyclophosphamide; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; RTX, rituximab.

The use of MMF is not included since KDIGO 2012 argued against its utility. Many randomized control trials (RCTs) and cohort studies proved that rituximab (RTX) and tacrolimus/cyclosporine can increase the rate of both complete and partial remissions, with a better safety profile than cyclophosphamide. However, the use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) is hampered by their high relapse rate and, consequently, they can be used in monotherapy only in the case of a moderate risk of progression. Cyclophosphamide (CYC), on the other hand, reduces the risk of kidney failure to a greater extent, but it should be used only in high-risk patients due to its toxicity burden. The cumulative dose of the latter should not exceed 36 g in order to avoid malignancy or 10 g to preserve fertility.

The definition of relapsing MN varies among different authors. While some authors define relapse as an increase in proteinuria above 3.5 g/d, the working group of KDIGO 2021 defined a relapse as an increase in proteinuria with a coexistent decrease in serum albumin. If a patient experiences a relapse after a first course of rituximab, a second course of the drug can be administered. On the other hand, if a relapse occurs after a course of CNI + steroid, rituximab can be added alone or in combination with CNI. Finally, if the first-line therapy consisted of cyclophosphamide + glucocorticoids, a second course of the same schedule can be repeated, accounting for the maximum dose tolerated, or, alternatively, CNI + rituximab or rituximab alone may represent a second-line therapy.

There is no consensus, on the other hand, about the proper definition of resistant disease. If anti-PLA2R antibodies are detectable before first-line therapy, the disease can be defined as resistant if the antibody titer is still high after one course of therapy. Conversely, proteinuria evaluation cannot be used since it can persist for up to 24 months after therapy. If patients are not PLA2R-positive, persistence of the nephrotic syndrome can define a resistant disease. In evaluating resistant disease, the first step consists in checking the adherence to therapy by measuring the levels of B cells, anti-rituximab antibodies, CNI and IgG or the development of leukocytopenia in patients using cyclophosphamide.

If the first line-line therapy consists of RTX, CNI can be added to the therapy if the eGFR is stable. If the eGFR is decreasing or if even CNI + RTX fails to achieve a response, a trial of cyclophosphamide + glucocorticoids can be made. On the other hand, if CNI represents the first attempt, RTX can be administered if the kidney function is stable; however, if it is unstable or if RTX did not achieve a response, an alkylating agent must be tried. If the latter represents the first-line therapy, RTX can be added before trying another course of alkylating agents. If patients fail to respond to either RTX or CYC, their enrolment in trials with experimental drugs is suggested (see “Novel therapeutic approaches for Membranous Nephropathy” below).

Intravenous methylprednisolone is usually administered in an inpatient setting, while RTX can be administered to both outpatients and inpatients.