Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Samir Z. Zard and Version 4 by Jessie Wu.

α-(Acyloxy)alkyl radicals of general structure 1 are key intermediates in the polymerization of vinyl esters 2, especially vinyl acetate (2, R = Me); however, their use in the synthesis of small molecules has remained underdeveloped.

- radical additions

- xanthates

- α-(acyloxy)alkyl radicals

- enones

1. Introduction

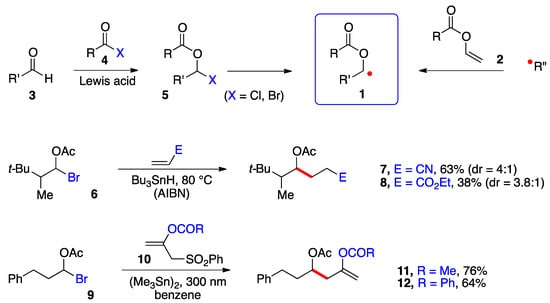

Perhaps the main impediment to produce and capture these radicals in a synthetically meaningful setting has been the relative inaccessibility and/or lability of precursors 5 (Scheme 1). α-(Acyloxy)alkyl chlorides (5, X = Cl) are easier to handle and purify than the bromides (X = Br) but are poorer radical precursors [1][2][1,2]. In most cases, such derivatives are prepared and used directly. Two types of transformations are pictured in Scheme 1. In the first, a classical Giese-type addition of bromide 6 to acrylonitrile and ethyl acrylate occurs to give adducts 7 and 8, respectively [3]. In the second, the radical from bromide 9 undergoes an addition–elimination onto alkenes 10 to give enol esters 11 and 12 [4]. Both studies relied on a stannane reagent to generate the desired radical intermediates. More recently, Glorius and co-workers generated the benzoylated ketyl radical 1 (R = Bz) from the in situ formed corresponding bromide 5 (R = Bz, X = Br) by irradiation (30 W 450 nm LED) in the presence of tris(trimethylsilyl)silane and an iridium catalyst and used a nickel catalyst to mediate its coupling with (hetero)aromatic bromides [5]. Nagib and colleagues used acetyl iodide and catalysis by zinc triflate to form in situ the geminal acetoxy iodide 5 (R = Ac, X = I) and produced the corresponding radical 1 (R = Ac) by reduction with Mn2(CO)10 in the presence of Hünig’s base (i-Pr2NEt) and irradiation with a blue LED. The radical was captured by an activated terminal alkyne or alkene in an iodine transfer Kharasch-type process [6]. In both of these more recent studies, relatively simple aldehydes 3 were used as starting materials. Only in one case was the iodide generated from a very particular ketone, namely 1,1,1-trifluoroacetone [6]. The strongly electronegative fluorine atoms protect the derived geminal acetoxy-iodide against elimination, allowing it to survive the radical addition conditions.

Scheme 1.

α-(Acyloxy)alkyl radicals and early examples of additions.

Another simple route to produce α-(acyloxy)alkyl radicals is by a radical addition to vinyl esters 2. However, while numerous instances of such additions have been reported, the resulting α-(acyloxy)alkyl radical intermediates were rarely used to create another carbon–carbon bond, with the obvious exception of oligomerizations and polymerizations. ResWearchers have found that by switching to the corresponding xanthates 13, practically all the limitations discussed above could be lifted, resulting in an unusually powerful synthetic tool. The present short resviearch w will hopefully provide the reader with an idea of the scope of this chemistry.

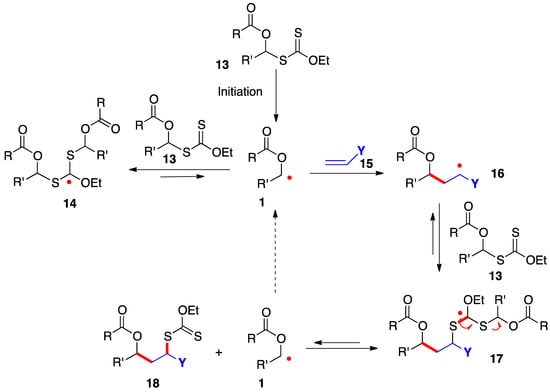

The radical addition of xanthates 13 to alkenes 16 proceeds by the simplified mechanism outlined in Scheme 2 [7][8][9][10][7,8,9,10]. Thus, radical 1, generated in an initiation step, is rapidly captured by the starting xanthate to give adduct radical 14; however, this step is reversible and degenerate and does not consume radical 1, which now acquires enough lifetime to allow it to add even to electronically unbiased alkene 15. The resulting adduct 16 in turn is reversibly intercepted by starting xanthate 13 to provide addition product 18 by fragmentation of intermediate 17. This sequence regenerates starting radical 1 to propagate the chain. The new carbon–carbon and carbon–sulfur bonds created in this process are colored in red.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of addition of α-(acyloxy)alkyl xanthates to alkenes.

In addition to providing key radicals 1 and 16 with extended lifetime, highly stabilized and bulky species 14 and 17 act as reservoirs for these radicals and lower considerably their absolute concentration in the medium. The consequences are less complications from unwanted radical-radical interactions and a greater scope as regards poorly reactive alkene traps. The actual mechanistic picture is in fact much more sophisticated than is conveyed in Scheme 2 and the interested reader is directed to references [9][10][9,10] for a more extensive discussion. It is also worth mentioning that while the sequence in Scheme 2 shows the addition to an alkene, the extended lifetime of the intermediate radicals can often be exploited to overcome the slow kinetics of other radical transformations, such as fragmentations, unusual ring-closures, cyclizations and additions onto aromatic derivatives, and inter- and intra-molecular hydrogen atom abstractions.

From a practical standpoint, this manner of generating and capturing radicals offers many advantages. It uses cheap, readily available, and non-toxic starting materials and reagents; it is metal-free, and especially tin-free, even though certain metal complexes can be used as photoredox initiators; it tolerates numerous functional groups and solvents, including water, and can be performed at high concentrations and even without solvent; last, but not least, almost all types of carbon centered radicals, as well as nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, phosphorus, and even stannyl radicals can be generated by this chemistry.

2. Synthesis

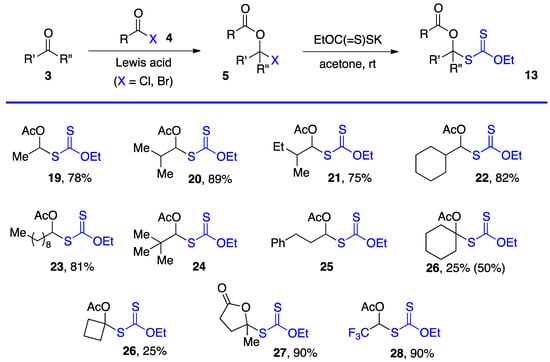

Researchers have employed two methods to obtain S-α-(acyloxy)alkyl xanthates 13, but various other approaches can be envisaged. The most direct is by substitution of α-(acyloxy)alkyl halides 5 by a xanthate salt. The chlorides (5, X = Cl) are most common and are prepared from aldehydes and, but to a lesser extent, ketones by reaction with an acid chloride under catalysis by a Lewis acid, most commonly zinc chloride [1][2][1,2]. Xanthates made by this route are assembled in Scheme 3 [4][11][12][13][14][4,11,12,13,14] (note that the same numbers 3, 5, and 13 for the generic structures in Scheme 1, Scheme 2 and Scheme 3 are used are for both aldehydes and ketone derived compounds). Examples 24 and 25 are taken from a study by Lee and Kim (but no yields are given) [4]. Xanthates 27 and 28 were prepared by somewhat different routes. The former is derived from levulinic acid by treatment with neat thionyl chloride followed by reaction with potassium O-ethyl xanthate [11]. For the latter, the steps were in a way reversed. First commercial methyl hemiacetal of trifluoroacetaldehyde is treated with the xanthate salt and cold sulfuric acid and the resulting geminal xanthyl alcohol acetylated with acetic anhydride with catalysis by sulfuric acid [13][14][13,14].

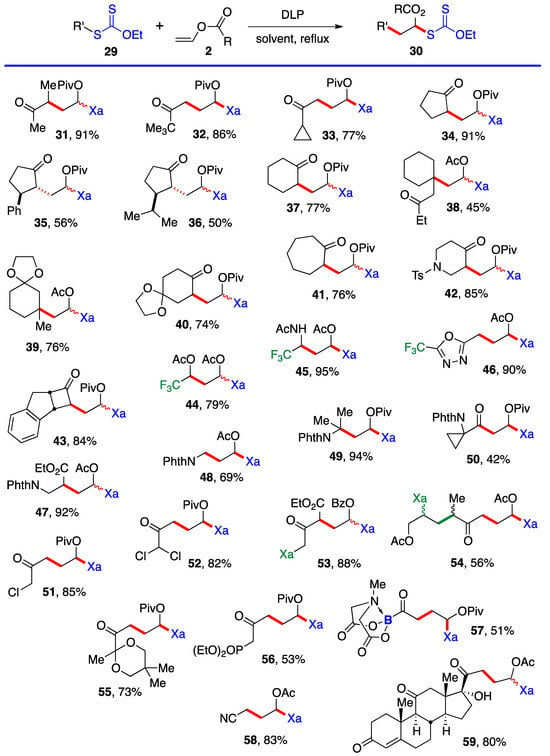

This first method is limited to aldehydes and to ketones that can withstand the strongly acidic conditions needed to form the α-(acyloxy)alkyl halides 5. Xanthates 19–28 in Scheme 3 are thus relatively simple unfunctionalized derivatives. Examples 24 and 25 are from the article by Lee and Kim [4] who, unfortunately, did not record the yield. The second approach is by the radical addition of a xanthate to a vinyl ester, as shown in Scheme 4. This is an infinitely more powerful strategy because of the large number of available xanthates and the mild experimental conditions that accommodate many functional groups. Examples 31–59 assembled in Scheme 4 concern aliphatic and alicyclic derivatives. The additions are simply accomplished by heating the xanthate and the vinyl ester in the solvent [most often ethyl acetate EtOAc, 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCE), or cyclohexane] under an inert atmosphere at typically a 1 M concentration and adding the DLP portion-wise to initiate the process (DLP is di-lauroyl peroxide, also sold under lauroyl peroxide, Laurox® or Luperox®). Upon heating to approximately 80 °C, DLP decomposes with a half-life of 1–2 h to give, after extrusion of CO2, primary undecyl radicals. These reactive radicals rapidly add to the thiocarbonyl group of the starting xanthate 13 to generate the more stable radical 1 by an addition–fragmentation analogous to the regeneration of radical 1 by reaction of adduct radical 16 with xanthate 13. In Scheme 4 and in following schemes, wherever applicable, the diastereomeric ratio is approximately 1:1 unless otherwise indicated.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of aliphatic and alicyclic α-(acyloxy)alkyl xanthates by radical addition to vinyl esters. Xa = -SC(=S)OEt; Piv = pivalate; Bz = benzoate; PhthN = phthalimido [13][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Ketones, protected or not, esters, nitriles, latent amines masked as phthalimides, phosphonates, nitriles, boronates, etc., can be present. α-Chloro- and α-dichloro-ketones 51 and 52 are particularly noteworthy in view of the sensitivity of these reactive motifs, especially the latter. In the case of di-xanthate 53, the xanthate next to the ketone (in green) can be used to accomplish a regioselective second radical addition to various alkenes, if so desired, without complications from the other xanthate (in blue). The radical derived from the “green” xanthate is stabilized by conjugation with the ketone and is easier to generate than the radical from the “blue” xanthate, which is the precursor of a less stabilized radical. This difference in relative stabilities is a powerful handle to control the order of additions. Indeed, this is how compound 54 was obtained, first by addition to allyl acetate (bonds colored in green) followed by the addition to vinyl acetate (bonds in red). Xanthates are unique in allowing a modular construction of densely functionalized complex structures by implementing multiple carbon–carbon bond forming processes.

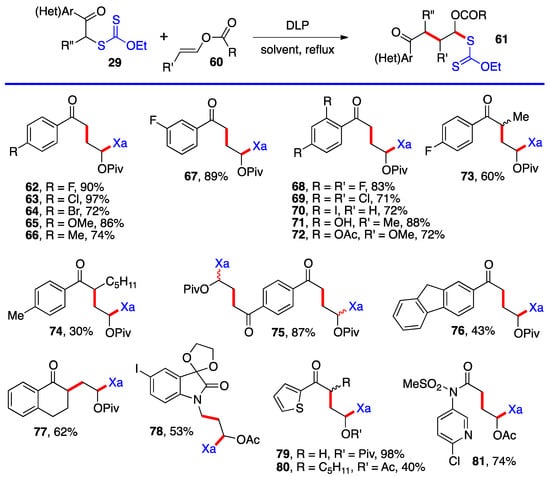

Aromatic and heteroaromatic derivatives 62–81 of generic structure 61, with the exception of compound 78 which is not derived from a ketonyl xanthate, are presented in Scheme 5. As will be shown later in this resviearchw, many of these adducts were used to prepare tetralones and naphthalenes by using the xanthate group to accomplish a ring-closure onto the aromatic or heteroaromatic ring.

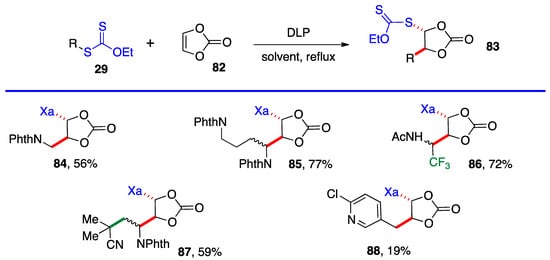

Most of the additions in Scheme 4 and Scheme 5 were performed on vinyl pivalate, in part because the yields are generally somewhat higher than with vinyl acetate, presumably because unwanted oligomerization is slower and competes less with the desired mono-addition. Substituted alkenyl esters (60, R’≠ H) react sluggishly and the yields are significantly lower, as illustrated by adducts 74 and 80. A special case is that of vinylidene carbonate 82 (Scheme 6). It has a reasonable reactivity and leads to interesting, highly functional trans adducts 83 which can be converted into protected vicinal diols. Five examples are displayed in Scheme 5. In the case of adduct 87, the xanthate used to react with vinylidene carbonate 82 is itself derived by addition of O-ethyl-S-(1-cyano-1-methyl)propyl xanthate to vinyl phthalimide. The bond formed in this addition is colored in green.

3. Radical Additions of S-α-(Acyloxy)alkyl xanthates

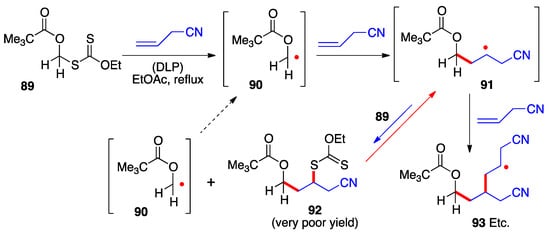

The examples in the preceding schemes give an idea of the range of functionalized structures of xanthates that can act as precursors for the corresponding α-(acyloxy)alkyl radicals. Their capture by an external alkene proceeds by the radical chain mechanism presented in Scheme 2. Implicit in this mechanistic manifold is the need for the starting radical 1 to be more stable than adduct radical 16 (neglecting for the moment polar factors), for otherwise the equilibrium between these two radicals, passing through intermediate 17, will favor the latter. The consequence is a significant unwanted oligomerization by further addition of adduct radical 16 to alkene 15. This untoward situation obtains in the case of the α-pivaloxymethyl xanthate 89 (Scheme 7) [23]. Its addition to allyl cyanide hardly produces any of the corresponding adduct 92 because primary radical 90 is not sufficiently stabilized by the pivaloxy group alone to make it more stable than adduct radical 91. The unfavorable equilibrium causes adduct radical 91 to accumulate leading to the predominant formation of oligomers (radical 93) and other side-products.

Scheme 7.

Failed addition of a primary α-(acyloxy)alkyl xanthate due to unfavorable relative stabilities of the intermediate radicals.

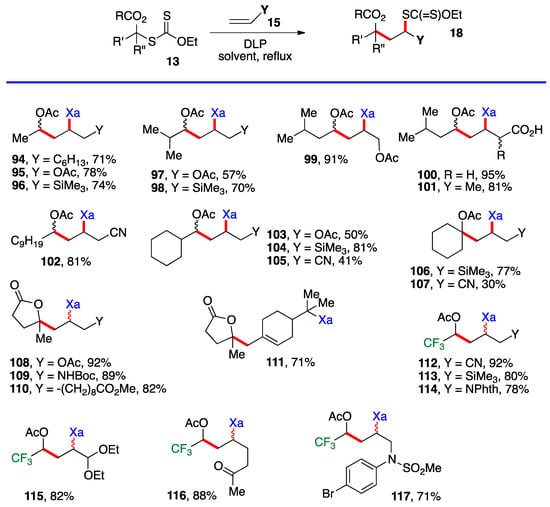

However, the difference in stability is slight and, once a substituent is introduced (i. e. 1, R’ ≠ H), the relative stabilities are reversed. The desired chain is now correctly propagated and furnishes the requisite addition products 18, as summarized by the generic equation at the top of Scheme 8. The reactions are carried out in the same manner as for the additions in Scheme 4, Scheme 5 and Scheme 6, namely by merely heating the xanthate and the alkene with portion-wise addition of the peroxide initiator. Examples 94–117 in Scheme 8 derive from the simpler xanthates in Scheme 3 (with the exception of cyclobutyl xanthate 26), which were obtained by chloroacetylation of aldehydes and ketones. Many of the synthetically most useful functional groups are tolerated on the alkene partner. The protected amines in examples 109 and 114, and the protected aldehyde and the free ketone in compounds 115 and 116 are especially noteworthy. Derivative 111 results from the addition–fragmentation of xanthate 29 to β-pinene.

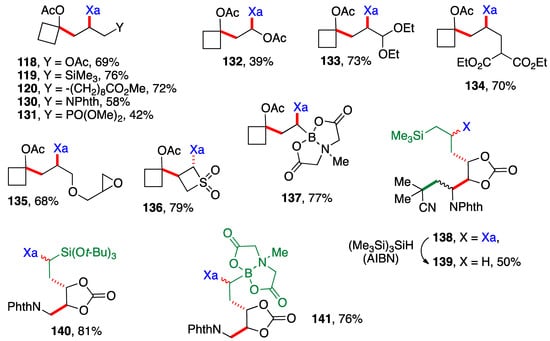

Scheme 9 presents examples of additions of cyclobutyl xanthate 26 (Scheme 3) and xanthates bearing the cyclic carbonate motif found in Scheme 6. The alkene partners are similar to those in Scheme 8, with a few additional interesting ones, namely the presence of an epoxide in adduct 135, a 4-membered sulfone in adduct 136 and a (MIDA)boronate in adducts 137 and 141 (MIDA = N-methyliminodiacetyl). The cyclic carbonate derivative 138 is in fact the result of three intermolecular additions with the creation of three new C—C bonds and one C—S bond (colored in green and red) and the modular combination of four different molecules. The xanthate was reductively removed to simplify the structure and spectral assignments. The yield given for sulfur-free product 139 is for the two steps which were telescoped. Incidentally, note that adduct 132 arises from addition of xanthate 26 to vinyl acetate and is thus also a precursor to an α-(acyloxy)alkyl radical. It could therefore in principle participate in a second radical addition if so desired. The moderate yield of adduct 132 is due to competing oligomerization.