Since the emergence of the concept of “buildability” in 1983, numerous studies have focused on improving project performance through buildability. Initially, the buildability discourse was based on narrow definitions and focused on aspects that could improve construction performance.

- buildability

- constructability

- key constructs

- technology

1. Introduction

2. Constructability and Buildability

The review of the literature indicates that the term “constructability” has historically been used interchangeably with buildability [19][20][21][22][19,20,21,22]. Ref. [23] stated that these two terms refer to similar concepts except in some instances where the term “constructability” had been used to explain the broader management implications of construction projects. According to the CII and CIIA, the key components of constructability include the application of construction knowledge at different work stages to achieve the overall project objectives, which is similar to the concept of buildability. Hence, some researchers argue that constructability and buildability are two identical concepts used in different parts of the world [19][20][21][22][24][19,20,21,22,24]. The Building Construction Authority (BCA) in Singapore, which has pioneered buildability research, stated in their latest publication that “buildability” is the responsibility of the professional team and “constructability” is the responsibility of the builder [25]. Therefore, although there is no clear demarcation between these two terms, most researchers agree that both terms carry similar meanings for the enhancement of construction project performance [26]. Hence, the term “buildability” is used here to encompass both “constructability” and “buildability” terms.3. Evolution of Buildability

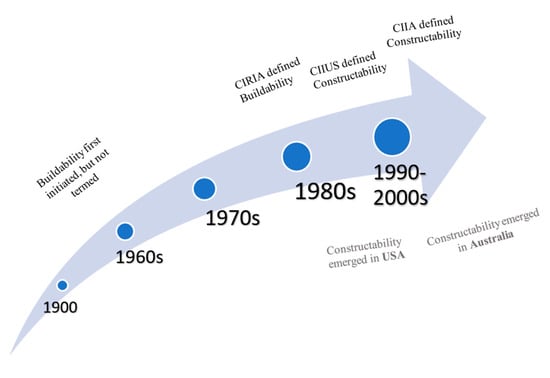

Buildability deals with integrating knowledge and expertise at the right time through the most appropriate source. Although the term “buildability” had not been framed until the early 1980s, concerns about the buildability concept can be traced back to the early 1960s. For instance, studies conducted from 1960 to 1970 indicated that the lack of integration of knowledge and experience within the framework of design and construction was the origin of many complex problems [27]. Owing to this, industry reports by Sir Harold Emmerson in 1962 and the Banwell Committee in 1964 extensively discussed the consequences of poor knowledge integration such as design and construction coordination issues, poor preparation of drawings and specifications, and the inadequate level of communication between the key stakeholders. Among these, ref. [28] extensively criticized the lack of cohesion in the industry and suggested improving “knowledge sharing between the designers and contractors” to minimize the issues. This can be identified as the earliest instance at which buildability was first cited. Later, ref. [29] introduced an “integrated-team” concept consisting of “multi-skilled, multi-functional” professionals, which could be identified as a means of addressing “buildability”, although it was not coined as a terminology. Figure 1 is a graphical illustration of the evolution of the buildability concept within major construction territories.

4. Key Constructs of Buildability

A previous study considering 11 definitions of the terms “buildability” and “constructability” that emerged over four decades (1983–2022) revealed that this concept has not evolved much over time [18]. Agreeing with this, numerous researchers confirmed that the most widely accepted and published definition was the one that CIRIA published in 1983 [17][33][34][35][36][17,33,34,35,36]. The following Table 1 presents the studies published on buildability in construction that refer to various definitions.|

Year of Publication and Reference |

Publication Title |

Major Focus |

Definition Referenced |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2012 |

[37] |

Critical success factors to limit constructability issues on a net-zero energy home |

Design & Construction |

(CII, 1986) |

|

2014 |

[38] |

The evaluation of constructability towards construction safety |

Design |

(CII, 1986) |

|

2015 |

[39] |

Modelling a decision support tool for buildable and sustainable building envelope designs |

Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2017 |

[40] |

AR (augmented reality) based 3D workspace modelling for quality assessment using as-built on-site conditions in remodeling construction project |

Design & Construction |

(CII, 1993) |

|

2017 |

[41] |

Beamless or beam-supported building floors: Is buildability knowledge the missing link to improving productivity? |

Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2018 |

[24] |

Enhancing off-site manufacturing through early contractor involvement (ECI) in New Zealand |

Early Design |

(CIIA, 1992) |

|

2019 |

[42] |

Concepts of constructability for project construction in Indonesia |

All Stages |

(CII, 1986) (CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2019 |

[43] |

An early-design stage assessment method based on constructability for building performance evaluation |

Early Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) (CII,1986) |

|

2020 |

[44] |

A systematic review of prerequisites for constructability implementation in infrastructure projects |

Early Design & Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) (CII, 1986) |

|

2021 |

[27] |

Constructability obstacles: An exploratory factor analysis approach |

Design |

(CII, 1986) |

|

2022 |

[44] |

Assessing design buildability through virtual reality from the perspective of construction students |

Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2022 |

[17] |

Buildability in the construction industry: A systematic review |

N/A |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2023 |

[10] |

Buildability attributes for improving the practice of construction management in Nigeria |

Design & Construction |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

|

2023 |

[20] |

Measures for improving the buildability of building designs in construction industry |

Design |

(CIRIA, 1983) |

5. Deconstruction of the Key Constructs of Buildability

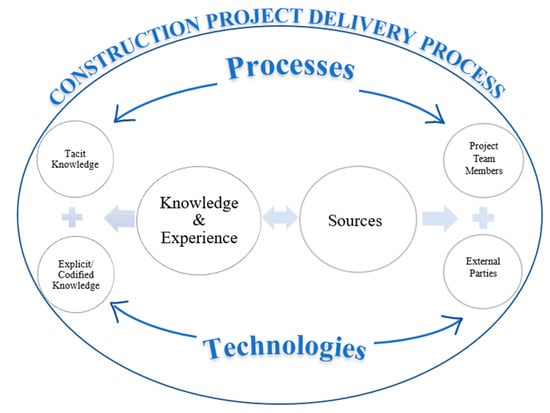

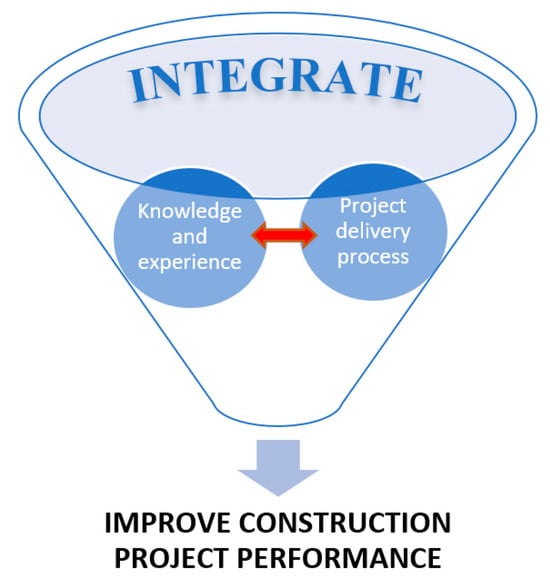

Figure 2 illustrates that the concept of buildability is based on integrating knowledge and experience throughout the project delivery process, and is aimed at achieving the overall project objectives. Therefore, the “integration of construction knowledge and experience” is identified as the key driver within the buildability concept [26]. Ref. [46] described knowledge as “the individual capability to draw distinctions, within a domain of action, based on an appreciation of context or theory, or both”. There are two main types of knowledge: explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge [47]. Explicit knowledge, which is also known as “codified knowledge”, can be expressed in words and numbers and shared in the form of data, scientific formulae, specifications, manuals, and the like [48]. Tacit knowledge, on the other hand, is highly personal and embedded in individual experience [49]. Tacit knowledge therefore partly consists of technical skills that are hard to pin down [50]. Subjective insights, intuition, and hunches fall into this category of knowledge. For this reason, “tacit knowledge” is referred to interchangeably with “experience” [51][52][51,52] or “know-how” [50]. As per [52], the reference to tacit knowledge is context-specific. In this context, tacit knowledge is mainly acquired through industry practice and the experience of the practitioners. Researchers agree that most knowledge in the construction sector is tacit rather than explicit [53]. Most tacit knowledge resides with people [54]. Therefore, people are the main source of knowledge in construction projects. People in construction projects include the project team members or the key stakeholders and the external stakeholders. Key stakeholders are the key source of knowledge in construction. Hence knowledge sharing between the key stakeholders is vital to incorporate buildability into construction projects [55]. Construction project stakeholders, as the key source of knowledge, come from various organizations and perform in a team to deliver the construction project [16][56][16,56]. Therefore, the construction project team is also referred to as a temporary multi-organization [57]. To manage the knowledge within an organization, people, technology, and well-designed processes are essential [58]. The next main construct of buildability refers to the project delivery process. In the majority of the studies, there is a consensus that the design stage is critical for implementing buildability [59][60][61][59,60,61]. However, CII in 1987 in their “Constructability Concept File” embraced all stages in building development for integration of construction knowledge, as each had its impact on achieving the overall project requirements. Similarly, many researchers criticized limiting buildability only to the design stage and argued that improvement measures were to be carried out throughout the whole building process [47][62][63][47,62,63]. Therefore, all stages of construction projects must require knowledge integration in order to get maximum buildability into the construction project [44]. Thus, all the work stages in the construction project are identified as key phases for integrating knowledge. Achieving real integration of people, technology, and processes throughout entire project delivery stages is challenging, as the contributions of the team members (sources of knowledge) throughout the project delivery stages are influenced by the procurement method of the project. For example, procurement methods such as the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) approach facilitate the integration of buildability naturally as collaboration among the stakeholders is enabled from the beginning itself and provides space for adapting modern technologies [64]. However, in procurement methods such as the traditional approach, buildability integration is difficult as this method naturally creates fragmentation among the stakeholders [65]. However, it has to be noted that the procurement method is decided irrespective of the concerns about buildability [66][67][66,67]. Therefore, this researchtudy focuses on buildability irrespective of the procurement method and attempts to derive key constructs that can provide guidelines for any construction project. Therefore, the selection of a suitable plan of work to capture the construction process is necessary. This plan of work has to identify the various stages in the construction process while being neutral about all the procurement methods. The RIBA Plan of Work 2020 addresses the work stages of all procurement methods as well as modern methods of construction or new drivers, such as sustainability and maintainability. The main constructs identified in the initial literesearchature review can be deconstructed as shown in Figure 3 below.