Endoscopy is an essential tool supporting inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis, and ileocolonoscopy is essential to the diagnostic process because it allows for histological sampling. A decent description of endoscopic lesions may lead to a correct final diagnosis up to 89% of the time. Moreover, endoscopy is key to evaluating endoscopic severity, which in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is associated with worse disease outcomes (e.g., more frequent advanced therapy requirements or more frequent hospitalizations and surgeries). Endoscopic severity should be reported according to validated endoscopic scores, such as the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) or the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) for ulcerative colitis, the Rutgeerts score for postoperative Crohn’s recurrence, and the Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) or the simplified endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) for luminal Crohn’s disease activity.

- endoscopy

- diagnosis

- prognosis

- central review

- agreement

- endoscopic scores

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis

The main diagnostic tool (of which the results should be integrated with the patient’s history, clinical feature interpretation, and laboratory and pathological findings) is ileocolonoscopy, which enables a reliable diagnosis in slightly less than 9 out of 10 of cases [1], allows tissue sampling to support pathological reports, and is considered the mainstay of IBD diagnosis per the current ECCO guidelines [2,3][2][3]. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) may involve variable extents of the small bowel and the colon; however, very commonly, the most representative pathological lesions lie in the colon or the terminal ileum, allowing for adequate visualization, characterization, and classification during an ileocolonoscopy. In a pivotal study, Pera et al. [1] reported that, when analyzing 606 colonoscopies carried out for known or suspected IBD, the accuracy of the colonoscopies was 89%, with 7% being indeterminate diagnoses and only 4% errors, which were numerically more likely in patients displaying the most severe inflammatory activity (in that subgroup, the occurrence of errors was more than doubled, reaching 9%). The study reported that the most useful endoscopic features for a differential diagnosis between CD and UC were discontinuous involvement, anal lesions, and cobblestoning of the mucosa (increasing the likelihood of a final diagnosis of CD) compared with erosions and mucosal granularity (increasing the likelihood of a final diagnosis of UC). According to the current ECCO guidelines, IBD diagnosis requires the integration of several clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings [2,3][2][3]. While all of these techniques are important, endoscopy, with its ability to collect biopsy specimens to support the diagnostic process, remains crucial. Moreover, the first (diagnostic) endoscopic examination contributes to a clear classification of the extent of the colon involved in the disease for ulcerative colitis, as well as the location of Crohn’s disease according to the Montreal classification [4]. It may also serve as a starting point for planning subsequent follow-ups and a priori risks of aggressive disease. If the endoscopic observation and its description are very precise, the endoscopic report can be of great value in reaching the correct final IBD diagnosis and characterization [5]. In the diagnostic process, endoscopy of the small bowel, either using capsule endoscopy (CE) or device-assisted enteroscopy (DAE), may also be needed. The evaluation of the small bowel is a strongly recommended step in Crohn’s disease, as well as when the ileocolonoscopy looks diagnostic for Crohn’s disease or when a diagnosis of IBD is unclassified [6]. In most cases, cross-sectional imaging is used to support the presence/absence of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement and extramural complications, such as abscesses, fistulas, or mesenteric hypertrophy. However, in selected cases, CE and DAE may be needed to exclude lesions relevant to the outcome, as a disease location in the jejunum or the proximal ileum is considered an adverse prognostic factor for a worse disease outcome of CD (upper gastrointestinal tract localization) [7]. Moreover, DAE can help with tissue sampling when a differential diagnosis in the small bowel includes small bowel lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, or small bowel tuberculosis, which is impossible using cross-sectional imaging and CE. Using a more diffuse diagnostic approach with CE to initially stage CD at diagnosis, or when CD is suspected, results in a higher reported risk of capsule retention (up to approximately 1 in 8 patients with known CD and 1 in 60 patients with suspected CD) [8]. Due to this increased risk, systematically performing a patency capsule test before a CE examination in known or suspected CD is strongly recommended. In summarizing the evidence on using endoscopy in IBD diagnosis according to the questions of ‘when’ and ‘how’ in this preseaperrch’s title, endoscopy is essential for IBD diagnosis. When? When a subject is suspected of being affected by IBD based on his/her clinical features, endoscopy is an essential diagnostic tool due to its very high intrinsic accuracy and specificity. Because of the disease’s high pretest probability, only a very accurate diagnostic technique is entitled to exclude or confirm a final diagnosis of IBD. How? Ileocolonoscopy with segmental biopsies is the preferred technique. The careful reporting of lesions, with the location and severity from the first examination, may impact the subsequent diagnosis and management of IBD patients [5]. Capsule endoscopy and disease-assisted enteroscopy may be chosen in selected cases [6].3. Severity Assessment

IBD endoscopic severity affects disease outcomes. This statement is supported by a large body of evidence, wherein the most severe endoscopic lesions are associated with the worst disease outcomes (an increased likelihood of surgery or no response to medical treatments) [9,10,11][9][10][11], while amelioration or healing of severe endoscopic lesions is associated with the best disease outcomes (less common clinical relapses, the least need for advanced treatments, and/or the lowest surgical risks) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Crohn’s disease patients with deep ulcerations involving a large part of a colonic segment had a 5–6-fold higher risk of needing a colectomy (and, therefore, sometimes also needing an ostomy) compared with patients without such lesions who were equally clinically active [9]. In that study, the occurrence of severe endoscopic lesions resulted in being a risk factor for surgery at least as important as experiencing severe clinical activity (defined by a Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) of greater than 288 points) or in being undertreated (defined by the absence of immunosuppressive treatment in the follow-up) [9]. Severe ulcerative colitis patients with severe endoscopic lesions were at a significantly higher risk of non-response to steroid treatment, leading to a 40-fold increase in the risk of urgent colectomy in a no-rescue treatment era [10]. Carbonnel and colleagues identified four types of severe lesions associated with a high risk of non-response to medical treatments, irrespective of exhibiting similar clinical activity:-

Deep and extensive ulcerations, bounded by swollen mucosa;

-

Mucosal detachment, which can be demonstrated by inserting the biopsy forceps under the edge of the ulceration;

-

Well-like ulcerations, visible as very deep ulcerations with a small diameter;

-

Large mucosal abrasions, formed by the junction of several deep ulcerations.

-

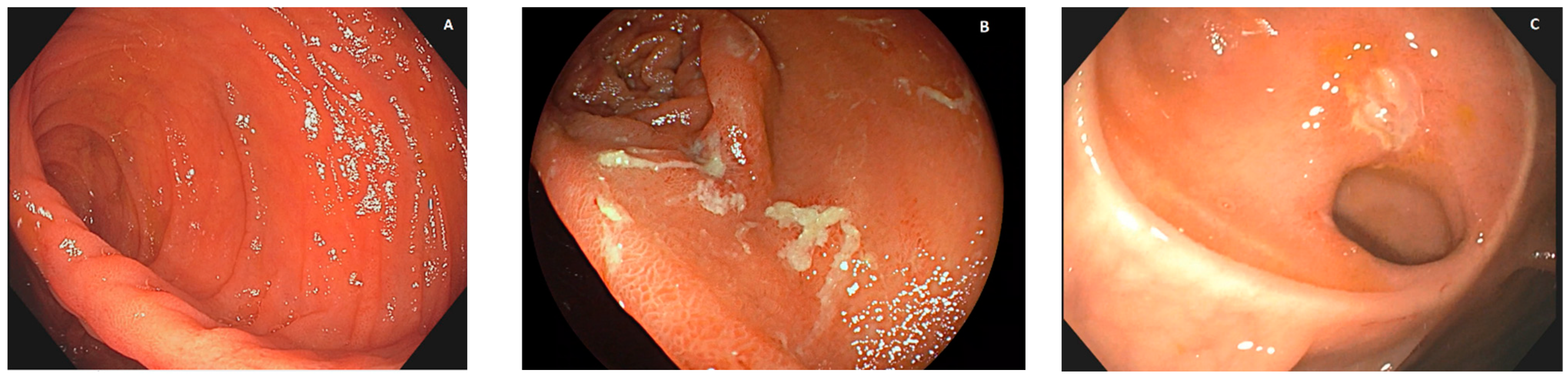

Patients with no recurrent lesions in the neoterminal ileum (i0; see Figure 1A) and those with up to five aphthous lesions in the neoterminal ileum (i1) had a clinical recurrence risk of 10% at 8 years;

-

Patients with more than five aphthous lesions in the neoterminal ileum with a normal mucosa between them, or with ulcers isolated from the anastomotic line (<1 cm), classified as i2, had a clinical recurrence risk of 40% at 5 years;

-

Patients with diffuse aphthous ileitis, with diffusely inflamed mucosa in between aphthae (classified as i3; see Figure 1B), had a clinical recurrence risk of 80% at 6 years;

-

Finally, patients with diffuse inflammation with already larger ulcers, nodules, and/or lumen narrowing (classified as i4; see Figure 1C) had a clinical recurrence risk of 100% at 4 years.

References

- Pera, A.; Bellando, P.; Caldera, D.; Ponti, V.; Astegiano, M.; Barletti, C.; David, E.; Arrigoni, A.; Rocca, G.; Verme, G. Colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnostic accuracy and proposal of an endoscopic score. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 181–185.

- Gomollon, F.; Dignass, A.; Annese, V.; Tilg, H.; Van Assche, G.; Lindsay, J.O.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Cullen, G.J.; Daperno, M.; Kucharzik, T.; et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 3–25.

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Borralho Nunes, P.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 144–164.

- Satsangi, J.; Silverberg, M.S.; Vermeire, S.; Colombel, J.F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006, 55, 749–753.

- Annese, V.; Daperno, M.; Rutter, M.D.; Amiot, A.; Bossuyt, P.; East, J.; Ferrante, M.; Gotz, M.; Katsanos, K.H.; Kiesslich, R.; et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 982–1018.

- Bourreille, A.; Ignjatovic, A.; Aabakken, L.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Eliakim, R.; Pennazio, M.; Bouhnik, Y.; Seidman, E.; Keuchel, M.; Albert, J.G.; et al. Role of small-bowel endoscopy in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: An international OMED-ECCO consensus. Endoscopy 2009, 41, 618–637.

- Wolters, F.L.; Russel, M.G.; Sijbrandij, J.; Ambergen, T.; Odes, S.; Riis, L.; Langholz, E.; Politi, P.; Qasim, A.; Koutroubakis, I.; et al. Phenotype at diagnosis predicts recurrence rates in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2006, 55, 1124–1130.

- Cheifetz, A.S.; Kornbluth, A.A.; Legnani, P.; Schmelkin, I.; Brown, A.; Lichtiger, S.; Lewis, B.S. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 2218–2222.

- Allez, M.; Lemann, M.; Bonnet, J.; Cattan, P.; Jian, R.; Modigliani, R. Long term outcome of patients with active Crohn’s disease exhibiting extensive and deep ulcerations at colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 947–953.

- Carbonnel, F.; Lavergne, A.; Lemann, M.; Bitoun, A.; Valleur, P.; Hautefeuille, P.; Galian, A.; Modigliani, R.; Rambaud, J.C. Colonoscopy of acute colitis. A safe and reliable tool for assessment of severity. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1994, 39, 1550–1557.

- Rutgeerts, P.; Geboes, K.; Vantrappen, G.; Beyls, J.; Kerremans, R.; Hiele, M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 956–963.

- Ardizzone, S.; Cassinotti, A.; Duca, P.; Mazzali, C.; Penati, C.; Manes, G.; Marmo, R.; Massari, A.; Molteni, P.; Maconi, G.; et al. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2011, 9, 483–489.e483.

- Baert, F.; Moortgat, L.; Van Assche, G.; Caenepeel, P.; Vergauwe, P.; De Vos, M.; Stokkers, P.; Hommes, D.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 463–468; quiz e410–461.

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D.; Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–1201.

- Louis, E.; Mary, J.Y.; Vernier-Massouille, G.; Grimaud, J.C.; Bouhnik, Y.; Laharie, D.; Dupas, J.L.; Pillant, H.; Picon, L.; Veyrac, M.; et al. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn’s disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 63–70.e65; quiz e31.

- Schnitzler, F.; Fidder, H.; Ferrante, M.; Noman, M.; Arijs, I.; Van Assche, G.; Hoffman, I.; Van Steen, K.; Vermeire, S.; Rutgeerts, P. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1295–1301.

- Solberg, I.C.; Lygren, I.; Jahnsen, J.; Aadland, E.; Hoie, O.; Cvancarova, M.; Bernklev, T.; Henriksen, M.; Sauar, J.; Vatn, M.H.; et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: Results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 431–440.

- Truelove, S.C.; Witts, L.J. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br. Med. J. 1955, 2, 1041–1048.

- Dal Piaz, G.; Mendolaro, M.; Mineccia, M.; Randazzo, C.; Massucco, P.; Cosimato, M.; Rigazio, C.; Guiotto, C.; Morello, E.; Ercole, E.; et al. Predictivity of early and late assessment for post-surgical recurrence of Crohn’s disease: Data from a single-center retrospective series. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2021, 53, 987–995.