Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Yew Kwang Hooi and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

In numerous electrical power distribution systems and other engineering contexts, single-line diagrams (SLDs) are frequently used. The importance of digitizing these images is growing. This is primarily because better engineering practices are required in areas such as equipment maintenance, asset management, safety, and others. Processing and analyzing these drawings, however, is a difficult job. With enough annotated training data, deep neural networks perform better in many object detection applications. Based on deep-learning techniques, a dataset can be used to assess the overall quality of a visual system

- DCGAN

- LSGAN

- synthetic images

- single-line diagrams

- symbol spotting

- image analytics

- CNN

1. Introduction

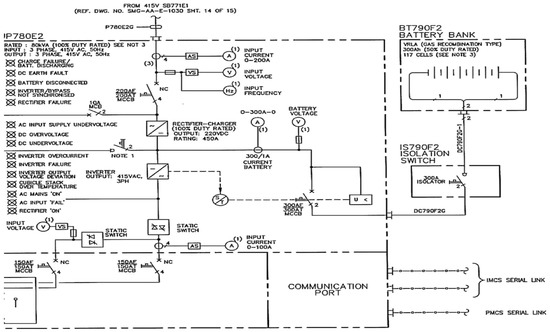

There are numerous industries in which engineering documents continue to exist in paper format due to a lack of digitalization for automated systems [1]. Among such documents, single-line diagrams (SLDs) pose a significant challenge in terms of interpretation and comprehension, as exemplified in Figure 1. These technical documents play a crucial role in diverse fields, including electrical systems, power distribution systems, hazardous area layouts, and other structural layouts. Deciphering these drawings often requires a considerable amount of time and the expertise of highly skilled engineers and professionals [2][3][2,3].

Figure 1.

A single-line diagram.

The digitization of engineering drawings has gained significant importance in recent years. This is partially due to the pressing need to enhance business procedures, such as equipment monitoring, risk analysis, safety checks, and other operations. It is also driven by the remarkable advancements in computer vision and image understanding, particularly in the fields of gaming and AI [4], NLP [5], health [6], and others. Machine learning and deep learning (DL) [7] have significantly improved performance in various domains. Machine vision, in particular, has greatly benefited from DL [8][9][8,9].

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have made remarkable progress in recent years and are widely used in various image-related tasks, including biometric-based authentication [10], image classification, handwriting recognition, and object recognition [11]. The advancements in image segmentation, classification, and object recognition prior to CNNs were incremental and limited. However, the introduction of CNNs has completely transformed this field [11]. For example, Taigman et al. introduced the DeepFace facial recognition system, which was first implemented on Facebook in 2014, achieving an accuracy of 97.35%, surpassing conventional systems by approximately 27% [12].

Despite notable advancements in image processing and analysis, the digitization of single-line diagrams (SLDs) and the automated interpretation of these drawings continue to pose significant challenges [13]. Presently, most methods rely on traditional image processing techniques that necessitate manual feature extraction. These approaches are highly domain-specific, susceptible to noise and data distribution variations, and tend to focus on addressing specific aspects of the problem, such as symbol detection or text separation. The performance of these models is greatly influenced by the quality of the provided training data.

Even in challenging and less-controlled environments, fundamental image segmentation and other processing tasks, such as object detection and tracking, have become considerably less difficult. Recent methods, such as faster regions with convolutional neural networks (Faster R-CNNs) [13], single-stage detection (SSD) [14], region-based fully convolutional networks [15], and You Only Look Once (YOLO) [16], have demonstrated high performance in object recognition and classification applications. These methods, along with their extensions, have addressed major obstacles, such as noise, orientation, and image quality, leading to significant advancements in this field of study [17].

Insufficient datasets for the training process pose another significant challenge in the digitization of engineering documents [18]. Deep-learning models require vast numbers of data for effective training. Given the industry’s heavy reliance on manual interpretation of these documents, there has been limited effort in generating the drawings automatically, making it challenging for researchers to acquire labeled data. To tackle this issue, data augmentation techniques have been introduced in recent years [19].

Generative models have also undergone significant advancement and have been effectively used in numerous applications. Generative adversarial networks have recently emerged as some of the most well-known and frequently employed tools for producing content. Ian Goodfellow first presented GANs in 2014 [20]. Another difficult issue that affects a wide range of fields, including engineering diagrams, is when several classes of symbols in the drawings are either over-represented or underserved in the dataset [21].

2. Digitization of Engineering Documents

Engineering drawings commonly incorporate diverse forms, symbolic shapes, solid or dashed lines, and text to depict intricate engineering processes in a condensed and comprehensive manner. These technical drawings find extensive application across multiple disciplines. Over the past decade, considerable research efforts have been dedicated to machine vision with the aim of digitizing these sketches [22][23][24][25][22,23,24,25]. With remarkable progress in computer vision and machine learning, coupled with the existence of vast numbers of undigitized legacy data, the need for a fully automated framework to digitize these drawings has become more imperative than ever before. One primary limitation of learning methods is their heavy reliance on extensive feature extraction, which is highly dependent on the quality of the extracted features and often lacks generalizability to unobserved instances [26]. The existing literature in this domain has primarily focused on addressing specific aspects of digitizing engineering diagrams, rather than providing a comprehensive and fully automated framework, as indicated by a recent comprehensive review [27]. Some studies have concentrated on the identification and categorization of common symbols in engineering drawings, as well as the separation of text from other graphical elements in diagrams, employing image processing techniques for line identification and deep-learning methods for symbol detection [28]. Alternatively, heuristic strategies have been employed in other studies to locate and classify components in drawings using approaches such as random forests, achieving precision levels exceeding 90% [29], or to discern and differentiate text from graphic elements [30][31][32][33][30,31,32,33]. However, these approaches may require the modification of heuristic rules or the development of new ones when there are changes to the schematic or symbol representations [34]. Additionally, the effectiveness of these approaches heavily relies on a balanced distribution of data across the dataset. In recent years, attempts have been made to apply deep-learning-based techniques to tasks similar to the digitization of engineering drawings [35]. Some studies have utilized techniques based on single-stage detection (SSD) to identify doors, windows, and furniture objects in floor-plan diagrams, yielding positive results [36]. However, these studies used small datasets with an insufficient number of furniture items in each drawing [37]. The unbalanced distribution of object classes within these datasets leads to a decline in performance [38][39][38,39]. Symbol recognition in process and instrumentation diagrams (P&IDs) is a closely related field. The complexity of P&IDs introduces various challenges in symbol recognition, including adjacent lines, overlapping symbols, unclear regions, and similarity between symbols [40]. A study evaluated four classification tools, namely, multi-stage deep neural networks, hidden Markov models, K-nearest neighbors, and support vector machines (SVMs), using both synthetic and original drawing sheet datasets [41]. Although the SVM model demonstrated the best performance, all techniques involved grouping symbols before classification and removing lines for clearer observation. Additionally, a faster R-CNN was employed to detect and classify handwritten symbols in technical diagrams, with a focus on specific document types, such as PFDs and flowcharts, achieving favorable results compared to traditional methods. Various frameworks have been proposed for interpreting engineering sheets and P&ID drawings using deep-learning models. The combination of heuristic-based methods with deep-learning techniques has shown promising results in component detection for engineering drawings. A two-stage process was employed, involving Euclidean metrics to connect pipeline tags and symbols, as well as the probabilistic Hough transform for pipeline detection, to localize symbols and text. Another approach utilized a fully linked convolutional neural network to develop symbol localization techniques [42]. A dataset comprising 672 process flow drawings was used to automate engineering drawings, resulting in improved performance compared to conventional methods. However, accurate detection of all components was not achieved, and the class accuracy for different components in the drawings was around 64.0%. To capture the time-varying signal produced by pen movements during the sketching process of a one-line hand-drawn electrical circuit diagram, hidden Markov models (HMMs) were utilized [43]. A dataset containing 100 hand-drawn sketches was examined for this purpose. The proposed approach, which employed HMMs, yielded promising outcomes. It achieved an accuracy of more than 83% in classifying the points associated with connector and symbol categories correctly. A circuit-diagram recognition system was developed to address sketch recognition as a dynamic programming problem, incorporating a novel technique called 2D-DP [44]. The 2D-DP technique demonstrated successful identification of interspersed symbols within the sketches. The method introduced a tolerant connectivity function cost, which proved effective in recognizing free-form sketches. The experiment involved analyzing 130 sketches containing ten different types of electrical symbols. Point-level measurements revealed that the novel approach achieved an accuracy of over 90 percent. A grammar-based parsing strategy for recognition of hand-drawn one-line diagrams was introduced to evaluate the system on UML use-case diagrams, showing an improved recognition accuracy [45]. However, further accurate and formal user studies are necessary to understand the strategy’s limitations and explore potential enhancements. The adoption of advanced deep-learning methodologies has resulted in significant improvements in the detection and recognition of notations and symbols in musical documents [46]. Techniques such as Faster R-CNNs, R-FCNs, YOLO, and SSD have been successfully applied to identify handwritten musical symbols, demonstrating superior performance compared to traditional structured image processing methods for symbol recognition and detection [21][47][21,47]. In summary, the existing research highlights a notable gap between the current state of machine learning and technical image comprehension. This discrepancy arises from the rapid progress in the field juxtaposed with the uneven and incremental advancements in a critical application area that has implications across various sectors.3. GAN Networks

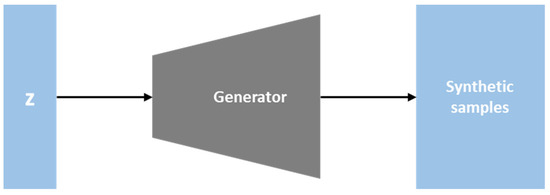

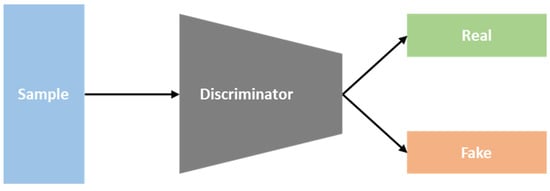

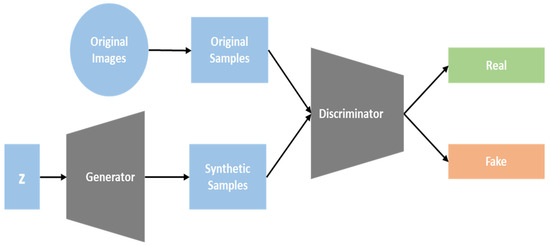

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) were first presented by Ian Goodfellow in 2014 [48]. GAN networks are thought of as generative models that can create unique and fresh content [21]. The generator (G) and the discriminator (D) are two competing models (such as CNNs, neural networks, etc.) that make up GANs. The discriminator serves as a classifier that receives input from the generator and the training set (fake input and authentic input). The discriminator will learn how to differentiate between real input samples and fake input samples fed into the network during the training procedure. However, the generator is taught to create samples that accurately reflect the fundamental properties of the original content [49]. As depicted in Figure 2, the generator is a network that uses current data to produce new, realistic pictures. An image is created using random noise z. The generator’s objective is to deceive the discriminator into believing that the fake image it produces is genuine [48]. Equation (1) is a possible way to describe this scenario. When a sample produced by the generator is discriminated against, the generator attempts to reduce the discriminator’s accuracy as much as possible [50].min

G

V(G) = E

z~px(z)

[log(1 − D(G(z))]

Figure 2.

The generator.

max

D

V(D) = E

z~px(z)

[logD(x)] + E

z~px(z)

[log(1 − D(G(z))]

Figure 3.

The discriminator.

min

G

max

D

V(D,G) = E

z~px(z)

[logD(x)] + E

z~px(z)

[log(1 − D(G(z))]

Figure 4.

Generative adversarial networks.