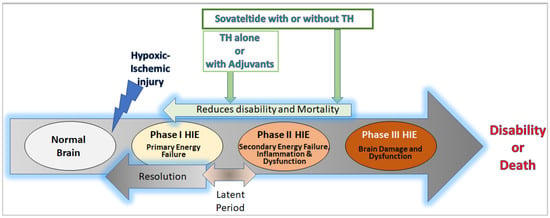

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a condition that results in brain damage in newborns due to insufficient blood and oxygen supply during or after birth. HIE is a major cause of neurological disability and mortality in newborns, with over one million neonatal deaths occurring annually worldwide. The severity of brain injury and the outcome of HIE depend on several factors, including the cause of oxygen deprivation, brain maturity, regional blood flow, and maternal health conditions. HIE is classified into mild, moderate, and severe categories based on the extent of brain damage and resulting neurological issues. The pathophysiology of HIE involves different phases, including the primary phase, latent phase, secondary phase, and tertiary phase. The primary and secondary phases are characterized by episodes of energy and cell metabolism failures, increased cytotoxicity and apoptosis, and activated microglia and inflammation in the brain.

- endothelin B receptors

- hypoxia

- ischemia

- neonates

- sovateltide

1. Introduction

2. HIE Pathology, Pathophysiology, and Neural Cell Damage

2.1. Pathology

The pathology of HIE starts with a reduced supply of blood in the fetal/neonatal brain, which leads to ischemic and hypoxic conditions with nutritional deprivation [8]. The severity of pathological impacts depends upon various factors, including the duration and intensity of interruptions in the blood supply, the age of the fetal/neonatal brain, and the affected brain regions. Depending upon the severity of these impacts, clinical manifestations in the central nervous system vary from one HIE patient to another. Mild HIE is known to cause transient behavioral abnormalities, e.g., poor feeding, irritability, excessive crying, or sleepiness in infants. Also, in the first few days of HIE, the affected neonates/infants seem hyperalert, with brisk deep tendon reflexes and slightly decreased muscle tone. Typically, mild HIE resolves in less than 24 h without any consequences. However, findings from recent years indicate otherwise, showing mild HIE linked with increasingly high adverse outcomes, including brain injury and neurodevelopmental impairment. It has been found that approximately 38–61% of neonates with mild HIE had abnormal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is like a moderate to severe HIE population [9,10,11,12][9][10][11][12]. Moreover, up to 25% of infants with mild HIE had neurodevelopmental impairment [13]. Moderate HIE, also known as “moderately severe HIE”, starts with a sudden deterioration in the neonatal/infantile brain, which has an initial period of well-being or mild hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy leading to dysfunction, injury, and death of the brain cell, causing seizures. Neonates/infants with moderate HIE are lethargic with diminished deep tendon reflexes and muscle tone (hypotonia). They have poor/no grasping, moro, and sucking reflexes, along with occasional periods of apnea. Seizure in neonates with moderate HIE is typical within the first 24 h of birth; however, full recovery from moderate HIE is possible within 1–2 weeks with a better long-term outcome [14].2.2. Pathophysiology and Neural Cell Death

Following hypoxic-ischemic injury, complex cascades of events occur in the brain at cellular and biochemical levels, which include oxidative stress, inflammation, excitotoxicity, and cell death (apoptosis/necrosis) [20][15]. During the early phase of hypoxic/ischemic brain injury, adaptive biochemical processes are started and lead to reduced temperature and increased release of neurotransmitters, e.g., gamma aminobutyric acid transaminase (GABA) in the brain, which reduce oxygen demand to minimize the impact of asphyxia [21][16]. However, spontaneous or interventional reperfusion in the hypoxic/ischemic brain activates various oxidative enzymes such as cyclooxygenase (COX), xanthine oxidase (XO), and lipoxygenase and leads to increased production of free radicals [22][17]. In the neonatal brain, the defensive antioxidant system to neutralize free radicals is poorly developed [23][18]. Consequently, a high amount of free radical production after reperfusion in the HIE brain causes peroxidation of lipids and damages proteins and DNA, leading to inflammation and cell death. Neural cell death is an evolving process and involves primary and secondary energy failures, which set the motion for deleterious biochemical and signaling cascades inducing neural cell dysfunction and death. A. Primary Energy Failure: Primary energy failure starts with reduced cerebral blood flow, leading to a depleted supply of oxygen and glucose in the HIE brain [2]. In this condition, energy (ATP) production is reduced while lactate production is increased [24][19]. Low ATP levels cause cellular machinery to fail to maintain membrane integrity, Na/K ion pumps, and intracellular Ca++ levels. In neurons, the failure of Na/K pumps causes excitotoxicity involving an excessive influx of positively charged Na ions, leading to massive depolarization [25,26][20][21]. Upon depolarization, neurons secrete a high amount of glutamate, a prominent excitatory neurotransmitter, which binds to the receptors present in neuronal and glial cells and promotes an additional influx of intracellular Ca++ as well as Na+. An increased level of intracellular Ca++ causes detrimental effects such as cerebral edema, microvascular damage, and cell death (apoptosis or necrosis) [27][22] In a chronic state of oxidative stress, ROS and RNS activate signaling pathways involved in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, and interferons (IFNs), which in turn also induce the production of ROS [42][23]. Thus, a vicious cycle of oxidative stress and inflammation starts. ROS and RNS act as regulators for inflammatory signaling pathways by oxidizing or nitrosylating amino acid residues of proteins involved in the signaling pathway. The inflammatory response is self-regulated in the balanced redox state; nonetheless, it leads to progressive tissue damage under oxidative stress. In the neonatal HIE brain, these inflammatory responses (neuroinflammation) are mediated through glial cells (microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes) as well as non-glial resident myeloid cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) and peripheral leucocytes [48,49,50,51,52][24][25][26][27][28]. These activated neuroinflammatory cells play a significant role in the progression of HIE by inducing neuronal dysfunction and death [53,54][29][30]. The activated neuroinflammatory glial cells are also known to secrete ample amounts of glutamate, which induces excitotoxicity and cell death in neuronal cells, as described in the primary energy failure phase [55][31].3. Current Interventions or Therapies for Neonatal HIE

Therapeutic Hypothermia

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) in neonates/infants involves lowering the temperature to 33.5 ± 0.5 °C for whole-body cooling and 34.5 ± 0.5 °C for selective head cooling [56][32]. Nonetheless, successful implementation of cooling protocols requires a multidisciplinary team, including core practitioners who are well-versed in established guidelines [56][32]. Presumably, it offers neuroprotection by reducing cerebral metabolic demand, decreasing the rate of oxygen consumption, lowering ATP demand, reducing excitatory neurotransmitters, stabilizing the blood-brain barrier, and reducing cerebral edema by decreasing permeability to inflammatory cytokines, free radicals, and thrombin [57,58,59,60][33][34][35][36]. However, the exact mechanism of action of TH remains unknown. Although the mechanism of action of TH remains elusive, TH has proven to be a valuable treatment for infants who have experienced acute perinatal insults such as placental abruption or cord prolapse. This therapy is most effective when administered to term and late preterm infants who are at least 36 weeks gestational age and are less than or equal to 6 h old [61][37]. To qualify for this treatment, infants must meet specific criteria, including having abnormal cord pH levels, a history of acute perinatal events, low Apgar scores, and signs of encephalopathy [61][37]. Initiating TH promptly is a critical factor in its effectiveness. In cases where infants need to be transported to specialized units, passive cooling measures such as removing the infant’s hat and blanket and turning off overhead warmers under the guidance of a neonatologist are recommended. It is vital to closely monitor the infant’s temperature during transport, ensuring it remains above 33 °C to prevent excessive cooling [61][37]. The rewarming process following TH is still debatable regarding the optimal rewarming rate. Primarily, a gradual approach of increasing the infant’s temperature by 0.5 °C every 1 to 2 h over 6 to 12 h is commonly used [61][37]. However, seizures or a worsening of clinical encephalopathy during rewarming have been reported. In such cases, temporarily stopping the rewarming process and returning to cooling for a 24-h period before resuming the rewarming process is recommended [62][38]. While therapeutic hypothermia can offer significant benefits, it is not without potential complications [63][39]. Some of these complications may include bradycardia (a slow heart rate), hypotension (low blood pressure) necessitating the use of inotropic medications, thrombocytopenia (a reduction in blood platelets), and pulmonary hypertension with impaired oxygenation. Additionally, infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) are susceptible to a range of other issues, such as arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms), anemia, coagulopathy (blood clotting disorders), and more. Therapeutic hypothermia is a valuable treatment option when administered correctly and carefully monitored to minimize brain injury and improve outcomes for newborns who have experienced perinatal insults. Various trials described below have shown the beneficial effects of TH over conventional care. Morphine reduces cortisol and noradrenaline, which could help protect neurons [73][40]. However, its effects on human newborns during hypothermia are uncertain. Neonatal seizures are common in HIE and are suspected to be an independent cause of brain injury, so using antiepileptic drugs as adjuncts to TH is common. Monitoring antiepileptic drug levels is crucial, especially if redosing is necessary. It is important to note that hypothermia can prolong the clearance of such drugs in newborns with HIE [74][41], so careful attention is required when using these adjunctive treatments. To further improve the TH outcomes, preclinical testing of several drugs in a rat model (Vannucci rat model) of HIE has been carried out and identified as potential therapeutics for treating HIE [75][42]. Unfortunately, none of them proved effective in clinical trials until now. Various adjuvants, including inhaled xenon, erythropoietin, darbepoetin, topiramate, allopurinol, stem cells, and sovateltide, are under trial or completed trial. The following sections will describe some prominent adjuvants and their trials in human patients.4. Therapies under Development for Neonatal HIE

4.1. Therapies under Development with Clinical Study Results

4.1.1. Xenon

Xenon is an odorless noble gas commonly used as an inhalation anesthetic in adults. Xenon has a rapid onset of action via inhalation and exerts anticonvulsant and electroencephalographic (EEG) suppressant effects in HIE neonates [76][43]. Several preclinical studies have shown its neuroprotective potential at subanesthetic concentrations of 50% xenon [76,77][43][44]. Xenon could significantly reduce brain injury in HIE animal models and had an additive neuroprotective effect when combined with TH immediately after the insult [76][43]. Other studies have also shown its neuroprotective role when administered before, during, and after an HIE [78][45]. Various concentrations ranging from 40% (Xe40%) to 70% (Xe70%) have been used; however, the optimal timing, dose, and duration of xenon treatment have not yet been optimized. When compared, Xe70% was seen as more neuroprotective than Xe50% in preclinical studies; nonetheless, the recommended dose is established at concentration ≤ Xe50%, which could induce sedation and allow substantial oxygen administration but avoid respiratory depression [76][43]. At the molecular level, xenon acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist and may prevent glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity [79][46]. It is known to interact with phenylalanine and bind to the glycine residue of the receptor [80,81][47][48]. Neuroprotective properties of xenon have been proven in cell culture [82][49] as well as in rodent and porcine models of hypoxia-ischemia [83,84,85,86,87,88][50][51][52][53][54][55]. Xenon is also known to activate ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels and two-pore domain potassium [K(2P)] channels, which play roles in neuroprotection [89,90][56][57].4.1.2. Erythropoietin and Darbepoetin

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hormone essential for erythropoiesis, produced primarily by the kidneys in mammals. The production of EPO is regulated through hypoxic cellular responses [95][58]. Typically, it is inversely proportional to oxygen level; for instance, during hypoxia, its production is elevated and provides a critical erythropoietic response to ischemic stress, e.g., during blood loss and at high altitudes [96][59]. In such a hypoxic condition, EPO gene expression is enhanced through the binding of HIF-2α to the hypoxic response element of the gene in EPO-producing cells [97,98][60][61] present in the kidneys or liver. EPO is released into the bloodstream and acts by binding to its receptor, EPOR, which is expressed on erythroid progenitor cells and non-erythroid cells such as neural cells, endothelial cells, and skeletal muscle myoblasts [99][62]. Its expression level is highest on erythroid progenitors and promotes their survival, growth, and differentiation needed to produce enough mature RBCs. While a feeble level of EPOR is present in non-erythroid cells, nonetheless, it supports the maintenance and repair of several non-hematopoietic organs, including the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle [100][63]. Hence, increased expression of EPO in hypoxia/ischemia could be protective for these non-erythroid organs; however, it negatively regulates adipogenesis and osteogenesis. Darbepoetin is a supersialylated analog of EPO generated by making five amino acid changes (N30, T32, V87, N88, and T90) in EPO. Darbepoetin contains two extra N-linked glycosylation chains than EPO; however, their tertiary structure and biological activity are identical. It also has greater metabolic stability and a lower clearance rate in vivo. The “elimination half-life” of darbepoetin in humans is three times greater than that of EPO (25.3 h versus 8.5 h). Darbepoetin has more stability, a longer half-life, higher biological activity, and decreased receptor affinity than EPO [101][64]. Overall, EPO and its analog, darbepoetin, mediate responses that are pleiotropic in nature and are involved in various physiological manifestations following hypoxia or ischemia. Therefore, they are being evaluated as a potential therapeutic target for HIE.4.1.3. Topiramate

Topiramate (TPM) is an approved anti-epileptic drug with neuroprotective potential. Its mechanism of action includes selectively blocking voltage-dependent sodium channels, enhancing the inhibitory effect of GABA receptors, and antagonizing glutamate receptors [113][65]. Although TPM is primarily used as an adjuvant drug for other anti-epileptic medications, it has shown promise as a potential treatment for seizures in neonates with HIE. Nevertheless, its use for this purpose is currently off-label, and limited research on TPM’s efficacy and safety in treating neonatal HIE has been conducted.4.1.4. Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are known to participate in various homeostatic activities such as blood pressure, the immune system, protein and carbohydrate metabolism, and anti-inflammatory action. Recent studies have shown that the administration of glucocorticoids to the neonatal brain through intracerebroventricular injection or intranasally can provide neuroprotection and improve brain damage after hypoxic-ischemic (HI) injury [115][66]. Hydrocortisone, a type of glucocorticoid, was tested in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center phase II/III study (NCT02700828). The study compared the effect of a low dose (0.5 mg/kg) of hydrocortisone vs. placebo on systemic low blood pressure during hypothermia treatment in asphyxiated newborns. Patients were treated with hydrocortisone (4 doses of 0.5 mg/kg/24 h) or placebo along with conventional inotropic therapy until the end of hypothermia treatment (max. 72 h). Results of the study showed that more patients achieved the target of at least a 5-mm Hg increment of the mean arterial pressure in 2 h in the hydrocortisone group compared with the placebo group (94% vs. 58%, p = 0.02, intention-to-treat analysis) [116][67]. The study concluded that hydrocortisone administration effectively raised the mean arterial blood pressure and decreased the inotrope requirement during hypothermia treatment in HIE neonates with volume-resistant hypotension.4.2. Future Therapies (Therapies under Development with Results Awaited)

4.2.1. Melatonin

Melatonin is widely known for regulating the circadian rhythm and is mainly produced by the pineal gland [117][68]. In addition to its role in circadian rhythm, it is known to serve as a free radical scavenger, inhibitor of inflammatory cytokines, and stimulant of anti-oxidant enzymes [118][69]. Therefore, its potential role in interrupting several key components in the pathophysiology of HIE and minimizing neural cell death is being explored. The safety, tolerability, and efficacy of melatonin are currently being examined in a phase I study (NCT02621944) in infants with HIE and treated with TH. A total of 30 subjects will be enrolled in the study. The first cohort of 10 subjects will receive 0.5 mg/kg of melatonin. If that dose proves to be safe, the second cohort of 10 subjects will receive a dose of 3 mg/kg of melatonin. After the safety assessment, the third cohort of 10 subjects will receive a dose of 5 mg/kg of melatonin. The study will assess various parameters, including the serum concentration of melatonin and adverse events. The long-term safety and potential efficacy via developmental follow-up will be performed at 18–22 months. In addition, the effect of melatonin on the inflammatory cascade, oxidative stress, free radical production, and serum biomarkers of brain injury in neonates will be evaluated. The efficacy of melatonin is also being assessed in another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on 100 neonates with HIE receiving TH (NCT03806816). Five daily enteral doses of melatonin (10 mg/kg) will be given to the neonates. The effect of melatonin will be assessed using aEEG, MRI, and spectroscopy analysis. Moreover, neurodevelopmental outcomes will be assessed using the Bayley Scales III at 6, 12, and 24 months.4.2.2. Caffeine

Caffeine is a widely consumed, naturally occurring stimulant of the methylxanthine class that acts on adenosine receptors [119][70]. It has FDA-approved medical uses, such as treating apnea of prematurity and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants [120][71]. There is ongoing research on its potential effectiveness in treating infants with HIE and neurocognitive declines in conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Caffeine affects adenosine receptors [121][72] in the CNS as well as the cardiovascular system, promotes positive inotropic effects in cardiac muscle, and stimulates the release of catecholamines. It also causes vasodilation through the antagonism of vascular adenosine receptors and the release of nitric oxide [122][73]. Adenosine is also involved in regulating inflammation. Therefore, caffeine’s antagonistic action on adenosine receptors reduces inflammation in certain conditions [123][74]. The half-life of caffeine in adults is approximately 5 h, but it can be significantly longer in newborns and premature infants (up to 8 h for full-term and 100 h for premature infants) due to differences in metabolism [120][71]. In animal models of HIE, caffeine helps reduce white matter brain injury [124][75].4.2.3. Citicoline

Citicoline is a form of cytidine 5-diphosphocholine (CDP-choline) and plays a crucial role in the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine from choline [126][76]. When taken orally, citicoline is rapidly absorbed and broken down into cytidine and choline in the gut. In the context of HIE, citicoline shows promise as a potential neuroprotector [127][77]. Some of the actions of citicoline include inhibiting glutamate accumulation, promoting the regeneration of injured cell membranes, increasing brain plasticity and repair, boosting the levels of useful neurotransmitters like dopamine and acetylcholine, and preventing the formation of free radicals [128][78]. Overall, citicoline holds potential as a therapeutic option for treating HIE by aiding in the repair and protection of neuronal cells.4.2.4. Metformin

Metformin is a widely used biguanide for managing type 2 diabetes [129][79]. It is highly permeable to the BBB and has pharmacological activities as an anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and anti-tumor agent, making it a potential drug candidate for CNS diseases [130][80]. Recent studies have demonstrated its neuroprotective effects in animal models of spinal cord injury and cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury [131,132][81][82]. It is also known to promote neurogenesis, the integrity of the BBB in experimental strokes, and remyelination in neonatal white matter after injury [133,134][83][84]. However, its effects on neonatal brain injury induced by hypoxic-ischemic events are still elusive, and further studies are required to understand its neuroprotective effects on HIE.4.2.5. Allopurinol

Allopurinol [4-hydroxy-pyrazole(3,4-d) pyrimidine], an inhibitor for xanthine oxidase (XO) [135][85], has been shown to have protective effects during ischemia. Inhibition of XO leads to reduced production of ROS and oxidative stress [136][86]; hence, it is suggested as a way to improve cardiovascular health. Some important ROS that could diminish due to XO inhibition include hydroxyl free radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and peroxynitrite, which can damage DNA, proteins, and cells. XO is also known to catabolize purines [137][87] in some species, including humans. Allopurinol is commonly used to treat various diseases such as gout, vascular injury, inflammation, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure. It is known to easily cross the blood-brain barrier and participate in neural cell protection [138][88]. It modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, reduces oxidative stress, and decreases pro-inflammatory molecules in the brain after injury. It has been found to inhibit axonal damage and demyelination caused by oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines. Studies have shown that allopurinol administration after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats reduces brain edema and neural cell death [139][89]. This neuroprotective effect is attributed to its ability to inhibit xanthine oxidase, which leads to reduced purine degradation and increased accumulation of purine metabolites, including adenosine, during hypoxia/ischemia.4.2.6. RLS 0071

RLS-0071 is a peptide with anti-inflammatory activity developed by RealAlta Life Sciences Inc. [140][90]. It is being studied as a potential treatment for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) and other rare diseases. The peptide consists of 15 amino acids and inhibits both humoral and cellular inflammation by blocking complement activation, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and neutrophil extracellular traps [140][90].4.2.7. Stem Cells

Multipotent stem cells are special types of cells that can self-renew and differentiate into different organ/tissue specific cell types [141][91]. Some of the well-known stem cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), mononuclear cells, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, neural stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells, endothelial cells, and inducible pluripotent stem cells, have shown promising therapeutic effects in hypoxic-ischemic damage [142][92]. The beneficial effects of these cells occur at both the cellular and functional levels. Overall, stem cells have the potential to create a favorable environment for tissue regeneration and lead to better functional outcomes following hypoxic-ischemic damage [142][92].4.2.8. Sovateltide

Sovateltide (IRL-1620 or PMZ-1620) is a synthetic analog of ET-1 and is a highly specific endothelin B (ETB) receptor agonist [146,147,148,149][93][94][95][96]. Several studies have demonstrated its beneficial effects on apoptosis, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, neuronal repair, and regeneration in the brain after injury, leading to improved neurological and motor functions [146,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158][93][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105]. Scholars are currently developing sovateltide as a “First-in-Class” therapeutic for treating ischemic stroke as well as neonatal HIE. Animal models of ischemic stroke have shown promising results, including improved hypoxia-induced survival factors, survival rates, reduced neurological and motor deficits, and decreased infarct volume, edema, and oxidative stress in the injured brain [146,149,151,152,153,155,156,157,158,159][93][96][98][99][100][102][103][104][105][106]. The phase I, II, and III clinical trials have concluded that sovateltide is safe, well-tolerated, and significantly effective in improving neurological outcomes in acute cerebral ischemic stroke patients at 90 days of treatment [160,161][107][108]. Because of similar pathophysiology (ischemia/hypoxia) and neural cell damage in ischemic stroke and HIE, sovateltide could be useful in curbing the pathophysiological progression of HIE by controlling the primary and secondary energy failure through increasing hypoxia-induced survival factors and reducing oxidative stress and cell death in the neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain.5. Conclusions

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a serious condition that arises due to perinatal asphyxia or ischemia and can lead to significant neurological impairments and even death in newborns. At present, TH is the only approved treatment for HIE, which helps in improving outcomes for infants with HIE, but it has serious shortcomings, including the requirement for costly equipment and management, high variability, poor long-term outcomes, and poorly understood mechanisms. Hence, drug development may focus on supporting and enhancing the efficacy of hypothermia as adjuvants or/and identifying effective treatments that can provide neuroprotection and improve long-term outcomes for affected infants. However, because of the complex and multifaceted nature of HIE, successful drug development requires a multimodal approach. Targeting multiple pathways involved in the injury process, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis, may yield more effective therapeutic outcomes. Developing neuroprotective agents that can limit the extent of brain injury after a hypoxic-ischemic event is crucial. These agents should ideally preserve brain tissue, promote neuroregeneration, and minimize secondary damage. Investigating the potential benefits of combining therapeutic agents with hypothermia as adjuvants could be a promising avenue. Numerous drugs are being evaluated as adjuvants to TH. Drugs like erythropoietin, darbepoetin, xenon, topiramate, and glucocorticoids showed promising results in pre-clinical studies; however, none of them have demonstrated a clear indication of efficacy in improving the long-term outcome in large clinical trials on HIE neonates. Some other therapeutic agents, such as allopurinol, melatonin, metformin, caffeine, citicoline, RLS0071, and stem cells, are being examined through various clinical trials as potential future drugs. The potential of sovateltide to be developed as a novel therapeutic agent to treat neonatal HIE with or without TH is being evaluated at Pharmazz. Sovateltide is being developed as a “First-in-Class” neural progenitor inducer-based therapeutic and has proven safety, tolerability, and efficacy in clinical trials conducted on acute ischemic stroke adult patients in India. Moreover, pre-clinical studies in the HIE animal model showed that sovateltide could also be effective in treating neonatal HIE, as it significantly reduced oxidative and hypoxic damage and induced angiogenesis as well as neurogenesis in the injured neonatal brain of the animal with HIE. Currently, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial to assess the long-term (24 months of age) safety and efficacy of sovateltide in neonates with HIE receiving SOC (NCT05514340; n = 40) is recruiting patients. Sovateltide has demonstrated the multimodal effects required for containing the hypoxic-ischemic injury and repairing it by inducing neuronal regeneration and function in the brain affected by HIE. It is anticipated that sovateltide and other future therapeutics that have multimodal action, such as stem cells, allopurinol, RLS 0071, etc., would have a higher potential to be developed as effective therapies or TH adjuvants for treating neonatal HIE and reducing mortality as well as neurodevelopmental disorders in the near future. In conclusion, drug development for neonatal HIE is a challenging and evolving field.References

- Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Zupan, J.; Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet 2005, 365, 891–900.

- Allen, K.A.; Brandon, D.H. Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy: Pathophysiology and Experimental Treatments. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2011, 11, 125–133.

- Bruschettini, M.; Romantsik, O.; Moreira, A.; Ley, D.; Thébaud, B. Stem cell-based interventions for the prevention of morbidity and mortality following hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, Cd013202.

- Andersen, M.; Andelius, T.C.K.; Pedersen, M.V.; Kyng, K.J.; Henriksen, T.B. Severity of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and heart rate variability in neonates: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 242.

- Yokomaku, D.; Numakawa, T.; Numakawa, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Adachi, N.; Nishio, C.; Taguchi, T.; Hatanaka, H. Estrogen enhances depolarization-induced glutamate release through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured hippocampal neurons. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 831–844.

- Fatemi, A.; Wilson, M.A.; Johnston, M.V. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the term infant. Clin. Perinatol. 2009, 36, 835–858, vii.

- Nair, J.; Kumar, V.H.S. Current and Emerging Therapies in the Management of Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy in Neonates. Children 2018, 5, 99.

- Riljak, V.; Kraf, J.; Daryanani, A.; Jiruska, P.; Otahal, J. Pathophysiology of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy—Biomarkers, animal models and treatment perspectives. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65, S533–S545.

- Gagne-Loranger, M.; Sheppard, M.; Ali, N.; Saint-Martin, C.; Wintermark, P. Newborns Referred for Therapeutic Hypothermia: Association between Initial Degree of Encephalopathy and Severity of Brain Injury (What about the Newborns with Mild Encephalopathy on Admission?). Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 195–202.

- Walsh, B.H.; Neil, J.; Morey, J.; Yang, E.; Silvera, M.V.; Inder, T.E.; Ortinau, C. The Frequency and Severity of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Infants with Mild Neonatal Encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 26–33.e21.

- Rao, R.; Trivedi, S.; Distler, A.; Liao, S.; Vesoulis, Z.; Smyser, C.; Mathur, A.M. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Neonates with Mild Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy Treated with Therapeutic Hypothermia. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, 1337–1343.

- Massaro, A.N.; Murthy, K.; Zaniletti, I.; Cook, N.; DiGeronimo, R.; Dizon, M.; Hamrick, S.E.; McKay, V.J.; Natarajan, G.; Rao, R.; et al. Short-term outcomes after perinatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: A report from the Children’s Hospitals Neonatal Consortium HIE focus group. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 290–296.

- Conway, J.M.; Walsh, B.H.; Boylan, G.B.; Murray, D.M. Mild hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy and long term neurodevelopmental outcome—A systematic review. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 120, 80–87.

- Pandav, K.; Ishak, A.; Chohan, F.; Edaki, O.; Quinonez, J.; Ruxmohan, S. Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy-Induced Seizure in an 11-Year-Old Female. Cureus 2021, 13, e16606.

- Northington, F.J.; Chavez-Valdez, R.; Martin, L.J. Neuronal cell death in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 743–758.

- Dickey, E.J.; Long, S.N.; Hunt, R.W. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy—What can we learn from humans? J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 1231–1240.

- Zhao, M.; Zhu, P.; Fujino, M.; Zhuang, J.; Guo, H.; Sheikh, I.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.K. Oxidative Stress in Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2078.

- Ozsurekci, Y.; Aykac, K. Oxidative Stress Related Diseases in Newborns. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2768365.

- Shankaran, S. Neonatal encephalopathy: Treatment with hypothermia. J. Neurotrauma 2009, 26, 437–443.

- Weilinger, N.L.; Maslieieva, V.; Bialecki, J.; Sridharan, S.S.; Tang, P.L.; Thompson, R.J. Ionotropic receptors and ion channels in ischemic neuronal death and dysfunction. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 39–48.

- Stys, P.K. Anoxic and ischemic injury of myelinated axons in CNS white matter: From mechanistic concepts to therapeutics. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998, 18, 2–25.

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 229–317.

- Ranneh, Y.; Ali, F.; Akim, A.M.; Hamid, H.A.; Khazaai, H.; Fadel, A. Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory markers in developing various chronic diseases: A review. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2017, 60, 327–338.

- Mallard, C.; Tremblay, M.E.; Vexler, Z.S. Microglia and Neonatal Brain Injury. Neuroscience 2019, 405, 68–76.

- Liu, F.; McCullough, L.D. Inflammatory responses in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 1121–1130.

- Min, Y.J.; Ling, E.A.; Li, F. Immunomodulatory Mechanism and Potential Therapies for Perinatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Damage. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 580428.

- Rayasam, A.; Fukuzaki, Y.; Vexler, Z.S. Microglia-leucocyte axis in cerebral ischaemia and inflammation in the developing brain. Acta Physiol. 2021, 233, e13674.

- Jha, M.K.; Jeon, S.; Suk, K. Glia as a Link between Neuroinflammation and Neuropathic Pain. Immune Netw. 2012, 12, 41–47.

- Leavy, A.; Jimenez Mateos, E.M. Perinatal Brain Injury and Inflammation: Lessons from Experimental Murine Models. Cells 2020, 9, 2640.

- Li, B.; Concepcion, K.; Meng, X.; Zhang, L. Brain-immune interactions in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 159, 50–68.

- Haroon, E.; Miller, A.H.; Sanacora, G. Inflammation, Glutamate, and Glia: A Trio of Trouble in Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 193–215.

- Peliowski-Davidovich, A.; Canadian Paediatric Society, F.; Newborn, C. Hypothermia for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 41–46.

- Wassink, G.; Gunn, E.R.; Drury, P.P.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. The mechanisms and treatment of asphyxial encephalopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 40.

- Cornette, L. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonatal asphyxia. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2012, 4, 133–139.

- Whitelaw, A.; Thoresen, M. Therapeutic Hypothermia for Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury Is More Effective in Newborn Infants than in Older Patients: Review and Hypotheses. Ther. Hypothermia Temp. Manag. 2023; ahead of print.

- Kurisu, K.; Kim, J.Y.; You, J.; Yenari, M.A. Therapeutic Hypothermia and Neuroprotection in Acute Neurological Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 5430–5455.

- Lemyre, B.; Chau, V. Hypothermia for newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 23, 285–291.

- Kendall, G.S.; Mathieson, S.; Meek, J.; Rennie, J.M. Recooling for rebound seizures after rewarming in neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e451–e455.

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A systematic review of safety and adverse effects in the practice of therapeutic hypothermia. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 1886–1894.

- Simons, S.H.; van Dijk, M.; van Lingen, R.A.; Roofthooft, D.; Boomsma, F.; van den Anker, J.N.; Tibboel, D. Randomised controlled trial evaluating effects of morphine on plasma adrenaline/noradrenaline concentrations in newborns. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005, 90, F36–F40.

- Frymoyer, A.; Bonifacio, S.L.; Drover, D.R.; Su, F.; Wustoff, C.J.; Van Meurs, K.P. Decreased Morphine Clearance in Neonates with Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy Receiving Hypothermia. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 57, 64–76.

- Sabir, H.; Maes, E.; Zweyer, M.; Schleehuber, Y.; Imam, F.B.; Silverman, J.; White, Y.; Pang, R.; Pasca, A.M.; Robertson, N.J.; et al. Comparing the efficacy in reducing brain injury of different neuroprotective agents following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in newborn rats: A multi-drug randomized controlled screening trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9467.

- Ruegger, C.M.; Davis, P.G.; Cheong, J.L. Xenon as an adjuvant to therapeutic hypothermia in near-term and term newborns with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD012753.

- Anna, R.; Rolf, R.; Mark, C. Update of the organoprotective properties of xenon and argon: From bench to beside. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2020, 8, 11.

- Esencan, E.; Yuksel, S.; Tosun, Y.B.; Robinot, A.; Solaroglu, I.; Zhang, J.H. XENON in medical area: Emphasis on neuroprotection in hypoxia and anesthesia. Med. Gas Res. 2013, 3, 4.

- Franks, N.P.; Dickinson, R.; de Sousa, S.L.; Hall, A.C.; Lieb, W.R. How does xenon produce anaesthesia? Nature 1998, 396, 324.

- Armstrong, S.P.; Banks, P.J.; McKitrick, T.J.; Geldart, C.H.; Edge, C.J.; Babla, R.; Simillis, C.; Franks, N.P.; Dickinson, R. Identification of two mutations (F758W and F758Y) in the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor glycine-binding site that selectively prevent competitive inhibition by xenon without affecting glycine binding. Anesthesiology 2012, 117, 38–47.

- Dickinson, R.; Peterson, B.K.; Banks, P.; Simillis, C.; Martin, J.C.; Valenzuela, C.A.; Maze, M.; Franks, N.P. Competitive inhibition at the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor by the anesthetics xenon and isoflurane: Evidence from molecular modeling and electrophysiology. Anesthesiology 2007, 107, 756–767.

- Petzelt, C.; Blom, P.; Schmehl, W.; Muller, J.; Kox, W.J. Prevention of neurotoxicity in hypoxic cortical neurons by the noble gas xenon. Life Sci. 2003, 72, 1909–1918.

- Dingley, J.; Hobbs, C.; Ferguson, J.; Stone, J.; Thoresen, M. Xenon/hypothermia neuroprotection regimes in spontaneously breathing neonatal rats after hypoxic-ischemic insult: The respiratory and sedative effects. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 916–923.

- Hobbs, C.; Thoresen, M.; Tucker, A.; Aquilina, K.; Chakkarapani, E.; Dingley, J. Xenon and hypothermia combine additively, offering long-term functional and histopathologic neuroprotection after neonatal hypoxia/ischemia. Stroke 2008, 39, 1307–1313.

- Ma, D.; Hossain, M.; Chow, A.; Arshad, M.; Battson, R.M.; Sanders, R.D.; Mehmet, H.; Edwards, A.D.; Franks, N.P.; Maze, M. Xenon and hypothermia combine to provide neuroprotection from neonatal asphyxia. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 182–193.

- Thoresen, M.; Hobbs, C.E.; Wood, T.; Chakkarapani, E.; Dingley, J. Cooling combined with immediate or delayed xenon inhalation provides equivalent long-term neuroprotection after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29, 707–714.

- Chakkarapani, E.; Dingley, J.; Liu, X.; Hoque, N.; Aquilina, K.; Porter, H.; Thoresen, M. Xenon enhances hypothermic neuroprotection in asphyxiated newborn pigs. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 330–341.

- Faulkner, S.; Bainbridge, A.; Kato, T.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Kapetanakis, A.B.; Hristova, M.; Liu, M.; Evans, S.; De Vita, E.; Kelen, D.; et al. Xenon augmented hypothermia reduces early lactate/N-acetylaspartate and cell death in perinatal asphyxia. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 133–150.

- Bantel, C.; Maze, M.; Trapp, S. Noble gas xenon is a novel adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel opener. Anesthesiology 2010, 112, 623–630.

- Gruss, M.; Bushell, T.J.; Bright, D.P.; Lieb, W.R.; Mathie, A.; Franks, N.P. Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 443–452.

- Watts, D.; Gaete, D.; Rodriguez, D.; Hoogewijs, D.; Rauner, M.; Sormendi, S.; Wielockx, B. Hypoxia Pathway Proteins are Master Regulators of Erythropoiesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8131.

- Koulnis, M.; Liu, Y.; Hallstrom, K.; Socolovsky, M. Negative autoregulation by Fas stabilizes adult erythropoiesis and accelerates its stress response. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21192.

- Rankin, E.B.; Biju, M.P.; Liu, Q.; Unger, T.L.; Rha, J.; Johnson, R.S.; Simon, M.C.; Keith, B.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1068–1077.

- Suzuki, N.; Gradin, K.; Poellinger, L.; Yamamoto, M. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible gene expression after HIF activation. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 356, 182–186.

- Noguchi, C.T.; Asavaritikrai, P.; Teng, R.; Jia, Y. Role of erythropoietin in the brain. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007, 64, 159–171.

- Dey, S.; Lee, J.; Noguchi, C.T. Erythropoietin Non-hematopoietic Tissue Response and Regulation of Metabolism during Diet Induced Obesity. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 725734.

- Egrie, J.C.; Dwyer, E.; Browne, J.K.; Hitz, A.; Lykos, M.A. Darbepoetin alfa has a longer circulating half-life and greater in vivo potency than recombinant human erythropoietin. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 31, 290–299.

- McLean, M.J.; Bukhari, A.A.; Wamil, A.W. Effects of topiramate on sodium-dependent action-potential firing by mouse spinal cord neurons in cell culture. Epilepsia 2000, 41, 21–24.

- Harding, B.; Conception, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Glucocorticoids Protect Neonatal Rat Brain in Model of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 18, 17.

- Kovacs, K.; Szakmar, E.; Meder, U.; Szakacs, L.; Cseko, A.; Vatai, B.; Szabo, A.J.; McNamara, P.J.; Szabo, M.; Jermendy, A. A Randomized Controlled Study of Low-Dose Hydrocortisone Versus Placebo in Dopamine-Treated Hypotensive Neonates Undergoing Hypothermia Treatment for Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2019, 211, 13–19.e3.

- Cipolla-Neto, J.; Amaral, F.G.D. Melatonin as a Hormone: New Physiological and Clinical Insights. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 990–1028.

- Chitimus, D.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Pavel, B.; Zagrean, L.; Zagrean, A.M. Melatonin’s Impact on Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Reprogramming in Homeostasis and Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1211.

- Janitschke, D.; Lauer, A.A.; Bachmann, C.M.; Seyfried, M.; Grimm, H.S.; Hartmann, T.; Grimm, M.O.W. Unique Role of Caffeine Compared to Other Methylxanthines (Theobromine, Theophylline, Pentoxifylline, Propentofylline) in Regulation of AD Relevant Genes in Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Wild Type Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9015.

- Abdel-Hady, H.; Nasef, N.; Shabaan, A.E.; Nour, I. Caffeine therapy in preterm infants. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2015, 4, 81–93.

- Daly, J.W.; Shi, D.; Nikodijevic, O.; Jacobson, K.A. The role of adenosine receptors in the central action of caffeine. Pharmacopsychoecologia 1994, 7, 201–213.

- Echeverri, D.; Montes, F.R.; Cabrera, M.; Galan, A.; Prieto, A. Caffeine’s Vascular Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2010, 2010, 834060.

- Rivera-Oliver, M.; Diaz-Rios, M. Using caffeine and other adenosine receptor antagonists and agonists as therapeutic tools against neurodegenerative diseases: A review. Life Sci. 2014, 101, 1–9.

- Yang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Xue, X.; Fu, J. Caffeine treatment started before injury reduces hypoxic-ischemic white-matter damage in neonatal rats by regulating phenotypic microglia polarization. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 1543–1554.

- Iulia, C.; Ruxandra, T.; Costin, L.B.; Liliana-Mary, V. Citicoline—A neuroprotector with proven effects on glaucomatous disease. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 61, 152–158.

- Salamah, A.; El Amrousy, D.; Elsheikh, M.; Mehrez, M. Citicoline in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in neonates: A randomized controlled trial. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 55.

- Alvarez-Sabin, J.; Roman, G.C. The role of citicoline in neuroprotection and neurorepair in ischemic stroke. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 1395–1414.

- Sanchez-Rangel, E.; Inzucchi, S.E. Metformin: Clinical use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1586–1593.

- Cao, G.; Gong, T.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ge, T.; Liu, J. Mechanism of metformin regulation in central nervous system: Progression and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113686.

- Yuan, Y.; Fan, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, W. Metformin Protects against Spinal Cord Injury and Cell Pyroptosis via AMPK/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2022, 2022, 3634908.

- Ruan, C.; Guo, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Lv, H. Neuroprotective effects of metformin on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e2335.

- Fang, M.; Jiang, H.; Ye, L.; Cai, C.; Hu, Y.; Pan, S.; Li, P.; Xiao, J.; Lin, Z. Metformin treatment after the hypoxia-ischemia attenuates brain injury in newborn rats. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 75308–75325.

- Sharma, S.; Nozohouri, S.; Vaidya, B.; Abbruscato, T. Repurposing metformin to treat age-related neurodegenerative disorders and ischemic stroke. Life Sci. 2021, 274, 119343.

- Lee, B.E.; Toledo, A.H.; Anaya-Prado, R.; Roach, R.R.; Toledo-Pereyra, L.H. Allopurinol, xanthine oxidase, and cardiac ischemia. J. Investig. Med. 2009, 57, 902–909.

- Kostić, D.A.; Dimitrijević, D.S.; Stojanović, G.S.; Palić, I.R.; Đorđević, A.S.; Ickovski, J.D. Xanthine Oxidase: Isolation, Assays of Activity, and Inhibition. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 294858.

- Liu, N.; Xu, H.; Sun, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Lu, W. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Hyperuricemia and Xanthine Oxidoreductase (XOR) Inhibitors. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1470380.

- Marro, P.J.; Mishra, O.P.; Delivoria-Papadopoulos, M. Effect of allopurinol on brain adenosine levels during hypoxia in newborn piglets. Brain Res. 2006, 1073–1074, 444–450.

- Kaya, D.; Micili, S.C.; Kizmazoglu, C.; Mucuoglu, A.O.; Buyukcoban, S.; Ersoy, N.; Yilmaz, O.; Isik, A.T. Allopurinol attenuates repeated traumatic brain injury in old rats: A preliminary report. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 357, 114196.

- Goss, J.; Hair, P.; Kumar, P.; Iacono, G.; Redden, L.; Morelli, G.; Krishna, N.; Thienel, U.; Cunnion, K. RLS-0071, a dual-targeting anti-inflammatory peptide—Biomarker findings from a first in human clinical trial. Transl. Med. Commun. 2023, 8, 1.

- Soliman, H.; Theret, M.; Scott, W.; Hill, L.; Underhill, T.M.; Hinz, B.; Rossi, F.M.V. Multipotent stromal cells: One name, multiple identities. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1690–1707.

- van Velthoven, C.T.; Kavelaars, A.; Heijnen, C.J. Mesenchymal stem cells as a treatment for neonatal ischemic brain damage. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 71, 474–481.

- Ranjan, A.K.; Gulati, A. Sovateltide Mediated Endothelin B Receptors Agonism and Curbing Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3146.

- Takai, M.; Umemura, I.; Yamasaki, K.; Watakabe, T.; Fujitani, Y.; Oda, K.; Urade, Y.; Inui, T.; Yamamura, T.; Okada, T. A potent and specific agonist, Suc--endothelin-1(8-21), IRL 1620, for the ETB receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 184, 953–959.

- Ramos, M.D.; Briyal, S.; Prazad, P.; Gulati, A. Neuroprotective Effect of Sovateltide (IRL 1620, PMZ 1620) in a Neonatal Rat Model of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Neuroscience 2022, 480, 194–202.

- Gulati, A.; Hornick, M.G.; Briyal, S.; Lavhale, M.S. A novel neuroregenerative approach using ET(B) receptor agonist, IRL-1620, to treat CNS disorders. Physiol. Res. 2018, 67, S95–S113.

- Gulati, A.; Kumar, A.; Morrison, S.; Shahani, B.T. Effect of centrally administered endothelin agonists on systemic and regional blood circulation in the rat: Role of sympathetic nervous system. Neuropeptides 1997, 31, 301–309.

- Kaundal, R.K.; Deshpande, T.A.; Gulati, A.; Sharma, S.S. Targeting endothelin receptors for pharmacotherapy of ischemic stroke: Current scenario and future perspectives. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 793–804.

- Leonard, M.G.; Briyal, S.; Gulati, A. Endothelin B receptor agonist, IRL-1620, reduces neurological damage following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res. 2011, 1420, 48–58.

- Leonard, M.G.; Briyal, S.; Gulati, A. Endothelin B receptor agonist, IRL-1620, provides long-term neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2012, 1464, 14–23.

- Leonard, M.G.; Prazad, P.; Puppala, B.; Gulati, A. Selective Endothelin-B Receptor Stimulation Increases Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in the Rat Brain during Postnatal Development. Drug Res. 2015, 65, 607–613.

- Leonard, M.G.; Gulati, A. Endothelin B receptor agonist, IRL-1620, enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis following cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2013, 1528, 28–41.

- Ranjan, A.K.; Briyal, S.; Gulati, A. Sovateltide (IRL-1620) activates neuronal differentiation and prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in adult mammalian brains following stroke. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12737.

- Ranjan, A.K.; Briyal, S.; Khandekar, D.; Gulati, A. Sovateltide (IRL-1620) affects neuronal progenitors and prevents cerebral tissue damage after ischemic stroke. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020, 98, 659–666.

- Briyal, S.; Ranjan, A.K.; Hornick, M.G.; Puppala, A.K.; Luu, T.; Gulati, A. Anti-apoptotic activity of ET(B) receptor agonist, IRL-1620, protects neural cells in rats with cerebral ischemia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10439.

- Cifuentes, E.G.; Hornick, M.G.; Havalad, S.; Donovan, R.L.; Gulati, A. Neuroprotective Effect of IRL-1620, an Endothelin B Receptor Agonist, on a Pediatric Rat Model of Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 310.

- Gulati, A.; Agrawal, N.; Vibha, D.; Misra, U.K.; Paul, B.; Jain, D.; Pandian, J.; Borgohain, R. Safety and Efficacy of Sovateltide (IRL-1620) in a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial in Patients with Acute Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 85–104.

- Keam, S.J. Sovateltide: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 1239–1244.