Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Abdeslam BOUDHAR and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

As a semi-arid/arid country located in the northwest of Africa, Morocco is facing serious water scarcity driven by the dual stresses of decreasing availability of water resources and increasing water demands. Virtual water trade could be an effective tool to alleviate water scarcity.

- virtual water trade

- water scarcity

- agricultural products

1. Introduction

We might start by saying that there is nothing more essential for life on earth than water. Human health, urban and rural settlements, food security, energy production, economic development, and healthy ecosystems are all water-dependent. Water is an essential input to undertake productive activities. Economic sector performance and growth depend heavily on water in every production process, either directly or indirectly. Nevertheless, it is far more than a production factor. Water has characteristics that make it a special economic good: it is essential for life and health, scarce, non-substitutable, not freely tradable, fugitive, and a complex system [1][2][1,2]. These characteristics make water a scarce economic good that cannot meet all demands.

Over the past 100 years, because of population increase, accelerating urbanization, new consumption habits, and economic growth, global water use has increased six-fold and continues to grow at a rate of around 1% per year [3]. Consequently, an increasing number of countries are reaching the limit at which water services can be sustainably provided. The United Nations estimated that about 2.3 billion people live in water-stressed countries, of which 733 million live in high and critically water-stressed countries [4]. As a result, 700 million people worldwide could be displaced by intense water scarcity by 2030 [5]. Under the current trend, the gap between global water supply and demand will reach 40% by 2030 [6]. Under the business as usual scenario, around 40% of the world’s population will live in areas with severe water scarcity by 2035 and ecosystems will become increasingly unable to provide fresh water [7].

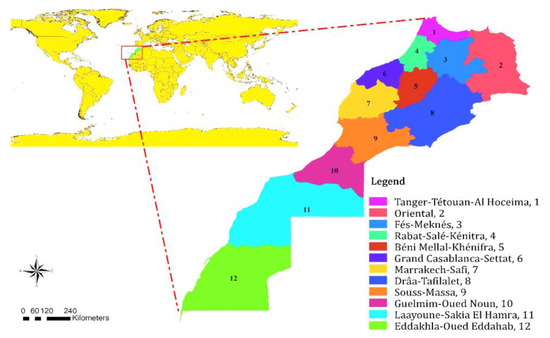

Morocco’s freshwater scarcity is deeply linked to its location in the northwest of Africa (Figure 1), in that its per capita available freshwater resource is only 650 m3 [8]. From 1960 to 2019, the available per capita renewable water resource in Morocco decreased from 2560 m3 to 650 m3. Moreover, water resource in Morocco is characterized by an uneven spatial-temporal distribution. The hydrographical map of the country is composed of nine hydrological basins. The two largest river basins, Sebou and Loukkos, are situated in the north of the country and contain about 47% of the total water resource, while they are home to only 19% of the total population and cover only 7.43% of the country’s area (Table 1).

Figure 1. Geographic location and regional division of Morocco. Source: author’s own.

Agriculture is the largest water-consuming sector in Morocco. It absorbs more than 87% of total water withdrawal. The definition of « Total water withdrawal » adopted in this study is that provided by FAO: Total water withdrawal is the annual quantity of water withdrawn for agricultural, industrial, and municipal purposes. It can include water from renewable freshwater resources, as well as water from over-abstraction of renewable groundwater or withdrawal from fossil groundwater, direct use of agricultural drainage water, direct use of (treated) wastewater, and desalinated water (https://www.fao.org/faoterm/en/?defaultCollId=7 (accessed on 26 March 2022)). Furthermore, irrigated agriculture is mainly export-oriented. Morocco’s foreign agricultural trade value has been booming since 2010. In 2017, exports of agricultural products represented more than 22% of Morocco’s total exports. The export volume increased by 59% since 2010. The international trade of agricultural products entails substantial flows of water in a ‘virtual’ form among countries. Therefore, assessing the impact of the international trade of agricultural commodities on water resources is helpful for understanding the driving forces behind water use and exploring new ways to mitigate the water scarcity problem in Morocco.

2. Virtual Water Trade

The impact of agriculture trade on water resources can be assessed using the “virtual water” concept. Since the 1990s, virtual water—or embedded water—has been emerging as a new perspective for water scarcity and water use management [9][10][10,11]. The virtual water concept was introduced by Allan in the 1990s [11][12][12,13]. It refers to the total volume of water used to produce a commodity. This volume depends on the production conditions including time and place of production and the efficiency of water use. The virtual water trade refers to virtual water transfers associated with the international trade of commodities. As a matter of fact, when a good is exported/imported, the virtual water used for the production of this good is also implicitly exported/imported. International trade is tied, therefore, to an indirect link between the water resources of a country and those of the countries with which it has trade relations.

In 1999, Allan [13][14] suggested that a country could implement the virtual water trade strategy by importing water-intensive products from another country and reducing the exports of products with high water consumption. For this purpose, the Virtual Water Trade analysis was developed to estimate the virtual water flow embodied in the trade of commodities. Many researchers have tried to assess the virtual water flow at global, regional, and national scales. At the global scale, virtual water trade research focuses more on the estimation of the global virtual water flows and the time series trends for virtual water trade [14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], and investigates the drivers of trade pattern formation [23][24][25][26][27][28][24,25,26,27,28,29].

At the regional scale, virtual water trade has been largely conducted in order to explore the virtual water flows among multiple countries in a region or among countries in a basin. For example, Serrano et al. [29][30] Antonellia et al. [30][31], Fu et al. [31][32], Wang et al. [32][33] investigated the virtual water flows in the EU. Vanham [33][34] assessed the virtual water balance for agricultural products in EU river basins. Duarte et al. [34][35] analyzed the virtual water embodied in Mediterranean exports between 1910 and 2010. Hakimian [35][36], Antonellia and Tamea [36][37], Roson and Sartori [37][38], Saidi et al. [38][39], Antonellia et al. [39][40], Lee et al. [40][41] analyzed virtual water flows and virtual water trade patterns in the MENA region. Yang et al. [41][42] investigated food trade patterns in relation to water resources in the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Virtual water trade has been largely analyzed at the national scale in China [42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52], Spain (e.g., [52][53][54][55][53,54,55,56]), Italy (e.g., [56][57][58][57,58,59]), Korea [59][60][61][62][60,61,62,63], and Brazil [63][64][65][66][64,65,66,67]. A few scholars have conducted quantitative studies on Morocco’s virtual water flows. For instance, Hoekstra and Chapagain [67][68] assessed the water footprints of Morocco and the Netherlands from 1997 to 2001. They found that Morocco depends 14% on foreign water resources, while the Netherlands depends on 95%. Boudhar et al. [68][9] implemented the concept of virtual water within an input-output framework. The model is used to quantitatively assess the relationships between economic sectors and water use (direct use), intersectoral water relationships (indirect use), and the economic benefits of water use. Haddad and Mengoub [69] estimated the virtual water exchanged between the Moroccan regions and the rest of the world through the implementation of the concept of virtual water in an interregional input-output model. However, there is no scholar who has analyzed the virtual water export and import in Morocco’s foreign trade of crop products and observed the changes over a long time. Therefore, the research on Morocco’s international virtual water trade of agricultural products needs to be enriched.