Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by Kareem Awad.

In light of the COVID-19 global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, ongoing research has centered on minimizing viral spread either by stopping viral entry or inhibiting viral replication. Repurposing antiviral drugs, typically nucleoside analogs, has proven successful at inhibiting virus replication.

- coronavirus

- COVID-19

- target cell responses

- drug design

- nucleoside analogs

- ACE2

1. Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019 has proven to be capable of causing a severe pneumonia, and the disease is referred to as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the coronaviridae family of viruses belonging to the genus beta-coronavirus [1]. On 11 March 2020, the global spread of COVID-19 led to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) escalation of the virus to that of a pandemic. As of January 2023, there has been 680 million confirmed cases, 6.7 million deaths, and more than 13 billion vaccine doses administered [2]. From COVID-19’s inception, researchers have sought to understand the factors that trigger severe illness. Yet, the development of severe symptoms does not appear to be unilaterally attributed to the viral load or the spread of the virus in the host; rather, the severity of the disease may involve host cell responses. As such, researchers are investigating the repurposing of pre-existing antiviral drugs, notably nucleoside analogs (NAs), along with antibiotics, corticosteroids, and other options for SARS-CoV-2 therapy.

2. Viral Entry and Host Cell Responses

2.1. Infection and Transmission

SARS-CoV-2 can enter the human body either by inhalation or by coming into contact with respiratory droplets containing viral particles, typically from someone sneezing, coughing, or talking [13,14][3][4]. Since the start of this pandemic, hundreds of variants have evolved, which has affected the outcome of the pandemic. In spring 2020, SARS-CoV-2 became more infectious and transmissible due to mutations in its spike (S) protein as well as in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and these variants gained the capacity to overrun the original SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan strain [15,16][5][6]. These variants, including Alpha, Beta, Delta, Kappa and Omicron and their many sublineages, swept across the world. The variants differ in their ability to replicate, transmit, and induce host cell responses in human cells [17,18,19,20][7][8][9][10]. It was later observed that compared to the early pandemic strains, Omicron variants showed a weaker replication efficiency and a slower interferon response, which indicated that accumulated mutations may contribute to viral adaptation [18,21,22][8][11][12].

2.2. ACE2 Receptor and Mediation of Virus Host Cell Entry

To infect humans, SARS-CoV-2, like the earlier SARS-CoV, uses the spike (S) protein to bind to its cell surface receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2) [12][13]. After binding to its receptor, the virus is endocytosed, the viral genome is released, and viral RNA is translated into nonstructural proteins; these compose the replication–transcription complex (RTC) [23][14]. ACE2 is expressed in the heart, kidneys, testes, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs [24][15]. The ACE2 receptor is part of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway and is vital in regulating inflammation and wound healing [25][16]. The interaction with the viral spike protein and the ACE2 receptor may result in a dysregulation of the RAAS pathway, reducing the levels of ACE2 and leading to increased angiotensin II production and inflammation [26][17]. The downregulation of ACE2 causes an increase in inflammatory cytokine release, also known as the cytokine storm [27][18]. The cytokine storm is an out-of-control production of inflammatory cytokines that leads to excessive inflammation in the lungs [28][19].

The viral spike S glycoprotein consists of two subunits: S1 and S2. The C-terminal receptor-binding domain of the S1 subunit acts on the recognition of the ACE2, while S2 subunit helps the fusion of viral membrane into host cell membrane. Following this binding, a transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) or other proteases such as furin or cathepsin L catalyze the cleavage of the S protein [29][20]. TMPRSS2 is a cell surface protease and thus mediates the cleavage of the S protein at the plasma membrane. However, cathepsin L is located in the endosomal compartment and thus mediates the cleavage within the endolysosome. Cell entry by SARS-CoV-2, therefore, depends on the target-cell proteases, with TMPRSS2 and cathepsin L remaining as the two major proteases involved in S protein activation [30][21].

Additional mediators have been reported to facilitate virus entry in some cell types. These include non-tyrosine kinase, neuropilin (NRP1), the kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM1), the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 2 (mGluR2), the heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5 or GRP78), the transmembrane glycoprotein CD147, and the G protein-coupled receptor mGluR2 (GRM2) [29,30][20][21]. Other molecules that may act as co-factors in the entry process include ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM17), which is involved the shedding of the ACE2 ectodomain, and heparan sulfate (HS), which mediates ACE2 viral entry [31][22]. Further strategies of infections incorporate specific binding sites such as O-linked or N-linked glycans on the outer membrane of SARS-CoV-2, and hence other host molecules such as sugars and sialic acids may act as potential virus receptors [32][23].

2.3. Host Cells Responses to SARS-CoV-2

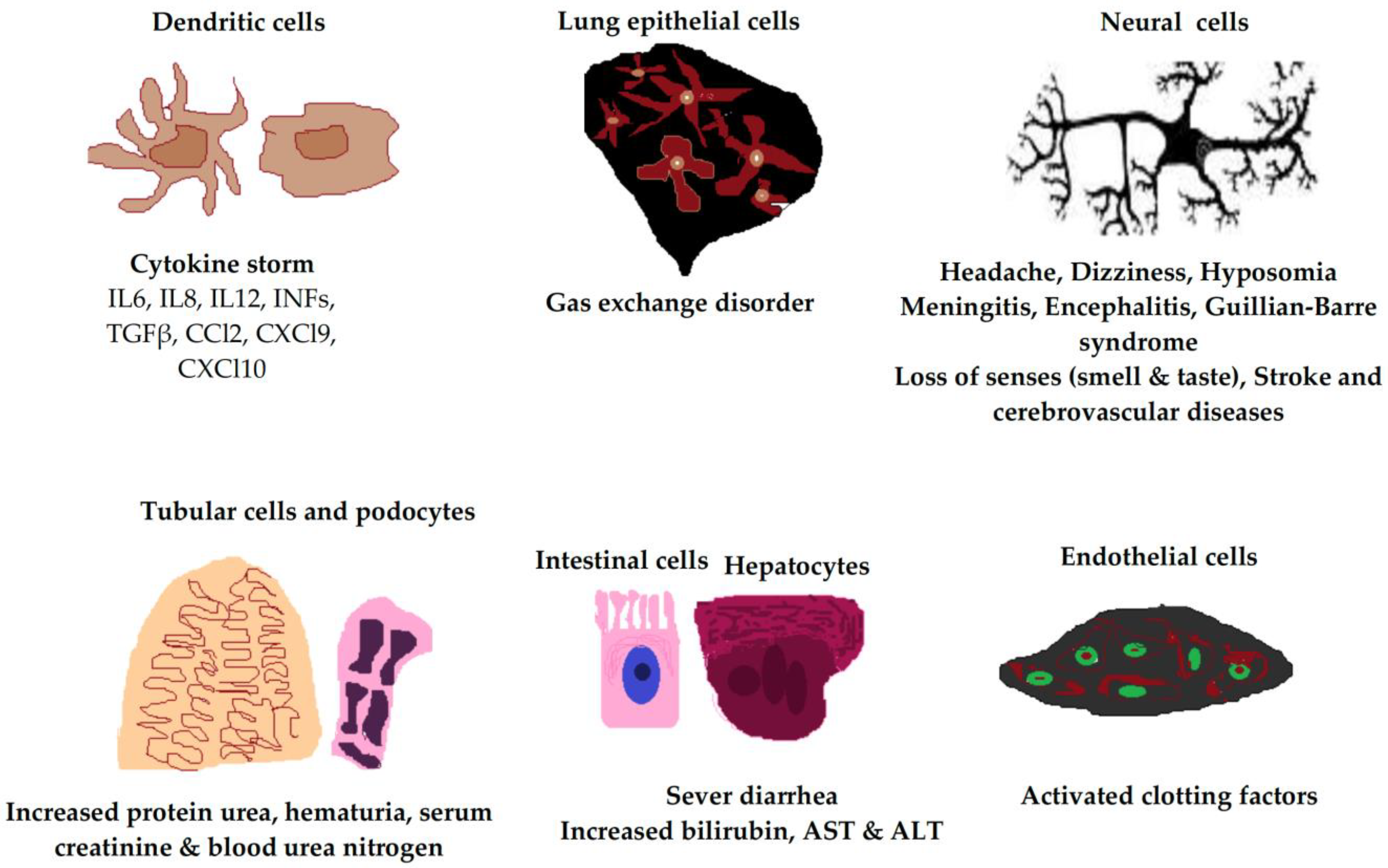

The factors that trigger severe illness in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 are not yet clearly defined, and the development of severe symptoms does not seem to be only related to the viral load or spread. Rather, severe disease appears to be associated with exaggerated host cell responses [33,34][24][25]. In this revisew, wearch, the researchers present current knowledge that focuses on host cell responses related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, including immune and nonimmune cell responses. The ACE2 receptor is expressed in many host cell types, including type 2 alveolar cells, ciliated cells, and goblet cells in the airways, which provide a port of entry for the virus in humans that leads to infection of the intestinal epithelium, cardiac cells, and vascular endothelia (Figure 1) [35,36][26][27].

Figure 1. Clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection in different human cell types due to ACE2 receptor expression. The ACE2 receptor is expressed in most cell types of the body, including neural cells, alveolar epithelial cells, immune cells, vascular endothelial cells, intestinal cells, hepatocytes, tubular cells, and podocytes. IL, interleukin; INF, interferon; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

3. Potential Drug Candidates and Clinical Trials for COVID-19 Treatment

Nucleoside analogs are RdRp inhibitors that can be used to treat different coronavirus infections, such as those caused by SARS and MERS [110,111][28][29]. The urgent demand for treatments has led the World Health Organization (WHO) to allow clinical trials of drugs that include: (a) hydroxychloroquine; (b) lopinavir; (c) ritonavir; (d) darunavir; and (e) remdesivir. Each have shown promising results for treatment of coronavirus infections [112][30]. However, the WHO and the FDA have halted most clinical trials due to lack of clinical evidence to support short-term recovery coupled with the inability to report possible long-term effects of emergency use of antimalarial and antiviral agents due to time constraints [113][31].

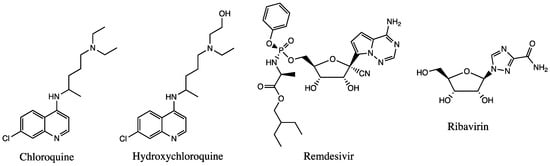

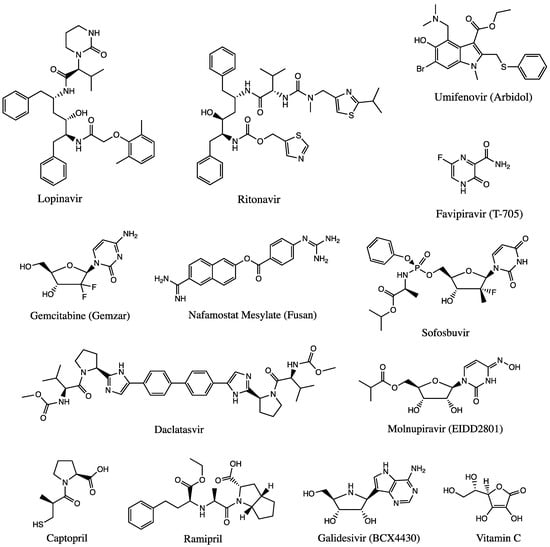

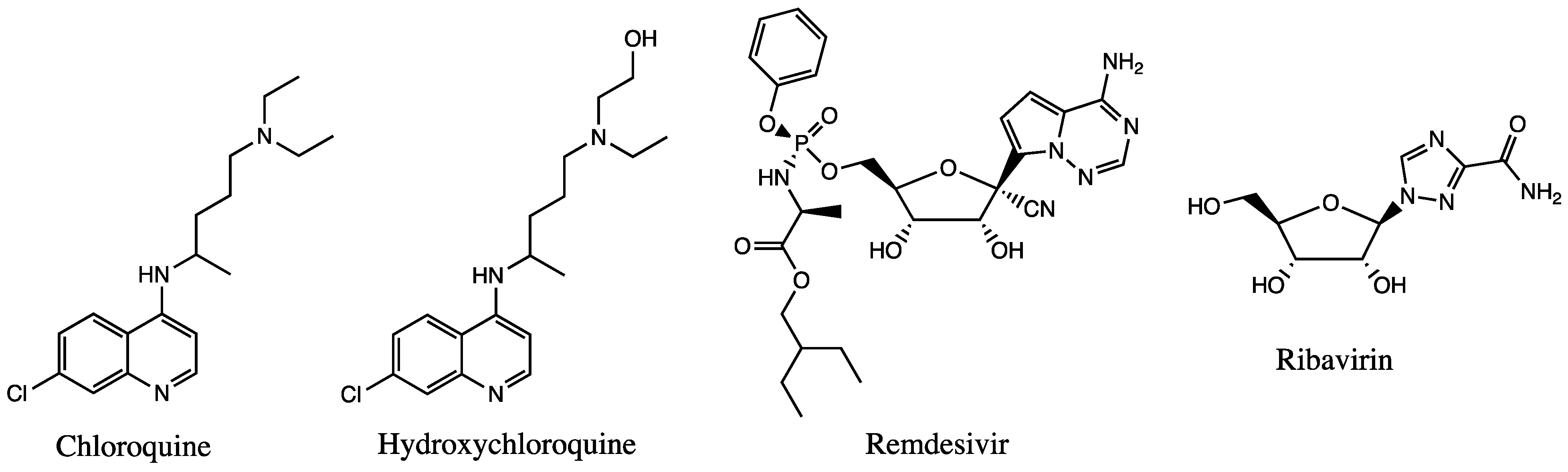

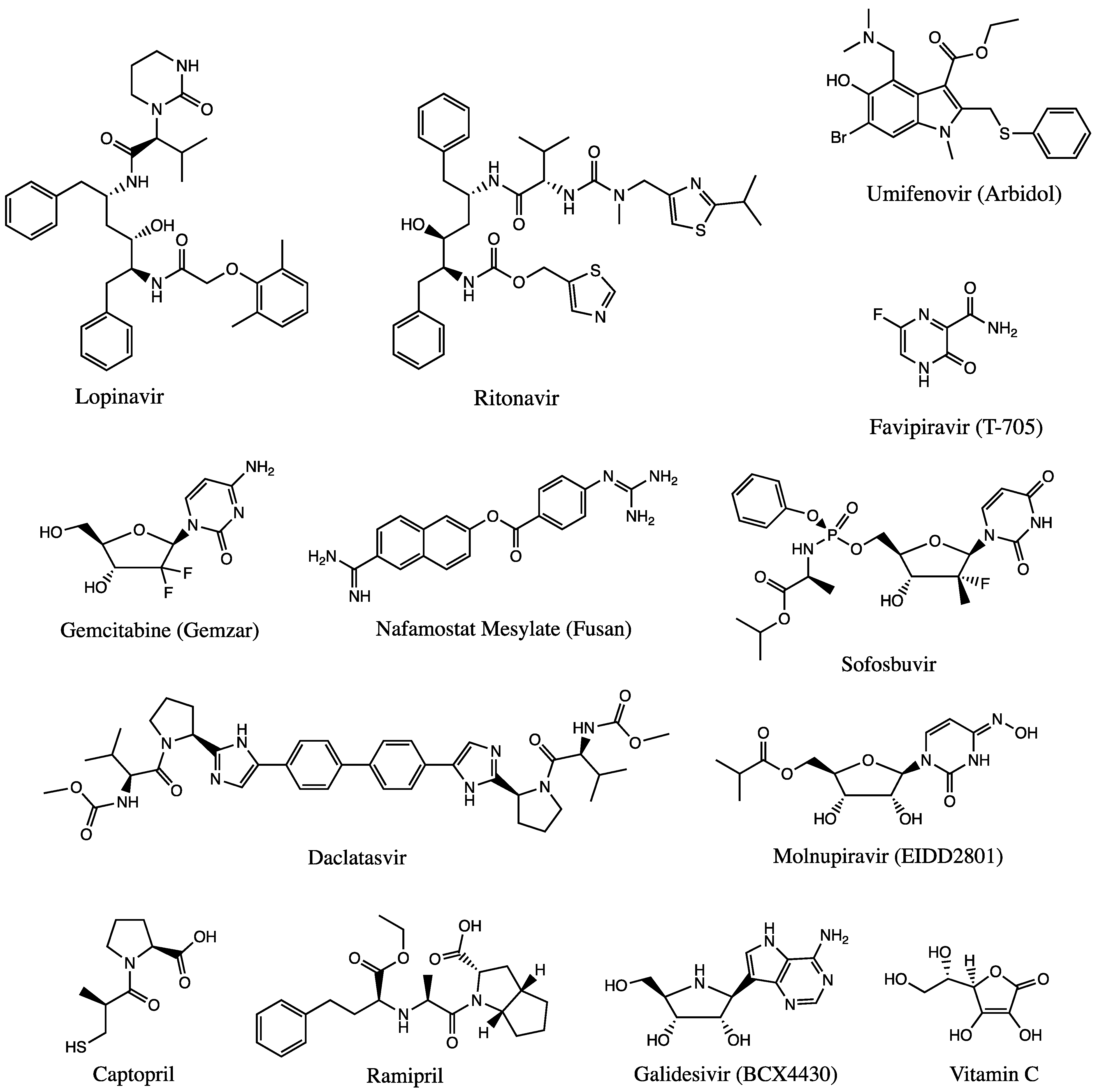

Several experimental clinical trials have concentrated on drug discovery and repurposing existing antiviral therapies, specifically those demonstrating prior effectiveness against MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV (Figure 2). Nafamostat, an inhibitor of MERS-CoV that prevents membrane fusion via the S protein, had an inhibitory effect against SARS-CoV-2 [114][32]. Notably, two compounds—remdesivir and chloroquine—inhibited viral infection at low-micromolar concentrations in vitro [8][33]. Each will be discussed in the sections below. Since the RdRp enzyme is highly conserved across all human coronaviruses, it is a prime target for inhibition by antiviral drugs, making remdesivir a front runner for COVID-19 treatment since it inhibits the RdRp activity [112][30].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of available drugs that have been investigated for the treatment of COVID-19.

3.1. Potential Candidates

3.1.1. Antimalarial Agents

Chloroquine (CQ) and Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ): Both are amino acidotropic forms of quinine and are FDA-approved to treat or prevent malaria and autoimmune diseases [115][34]. They have shown to prevent the entry and transport of coronaviruses by increasing the endosomal pH required for virus and cell fusion and interfering with the glycosylation of cell receptors [116][35]. CQ and HCQ were expected to prevent the replication and invasion of the virus and inhibit T-cell activation, reducing the risk of a cytokine storm [117][36]. On 15 June 2020, the FDA determined that CQ and HCQ are unlikely to be effective in treating COVID-19 due to serious cardiac adverse events and other serious side effects, concluding that these medicines showed no benefit for decreasing the likelihood of death or expediting recovery for hospitalized patients and ultimately revoking the emergency use of CQ and HCQ [118][37].

3.1.2. Antiviral Agents

Remdesivir (GS-5734) is an adenosine triphosphate nucleoside analog that interferes with virus replication and has been recognized as a promising antiviral drug against a plethora of RNA viruses, including Ebola, SARS, and MERS. However, its safety and efficacy are currently being tested in multiple clinical trials [119,120][38][39]. Remdesivir has been reported to inhibit viral RdRp activity at early stages of the infection cycle, and the incorporation of its active triphosphate form by the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex is higher than that of the competing natural ATP substrate, disrupting replication of the virus [121][40]. In June 2020, the FDA approved remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 requiring hospitalization. This approval was supported by analysis of data from three randomized, controlled clinical trials that included patients hospitalized with mild to severe COVID-19 [122,123][41][42].

Ribavirin is a guanosine nucleoside analog known as a broad-spectrum antiviral that is effective against HIV, hepatitis C, herpes viruses, and other viruses [124,125][43][44]. Ribavirin interferes with RNA polymerase and RNA capping, interrupting the viral cells’ ability to replicate, causing recognizable degradation. Treatment plans typically combine ribavirin with interferon-α2a or β1 [124][43]. Ribavirin monotherapy for MERS has shown little positive effect on patients with severe symptoms. There was hope that combination therapy of ribavirin with lopinavir/ritonavir against hCoV infections would be effective [126,127][45][46]. A phase II trial in March 2020 found that such a triple therapy was successful at early stages of COVID-19 in reducing the length of hospital treatment [128][47]. However, in July 2020, the NIH withdrew support of the use of ribavirin treatment as it did not reduce COVID-19 mortality [129][48].

Interferons (IFNs) are secreted antiviral cytokines that are produced by virus-infected cells. IFNs are broad-spectrum antivirals with α, β, and λ subtypes that have been used for the treatment of hepatitis and have been previously tested to treat MERS and SARS-CoV [130][49]. However, trials for IFN therapy (α or β) for hCoVs have shown variable results. Two clinical trials for SARS patients with IFN treatment determined that while IFN-α was able to inhibit SARS replication, IFN-β had similar results when used as a combination therapy [131][50]. Another study deemed IFN-β1b the preferred treatment for MERS and IFN-α2b/ribavirin for SARS, while several trials suggested that IFN-α2b/ribavirin could also be effective against MERS [132,133][51][52]. In a large randomized controlled trial of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the combination of IFN-β1a plus remdesivir showed no clinical benefit when compared to remdesivir alone [134,135][53][54]. Trials evaluating IFN-α were not sufficient to determine whether this agent provides a clinical benefit for patients [136,137][55][56].

Lopinavir/Ritonavir (LPV/RTV) are antiviral agents that act as HIV protease inhibitors that have been used for the treatment of SARS and MERS [138][57]. Lopinavir is commonly combined with ritonavir to increase its half-life and reduce side effects [139][58]. LPV and RTV along with interferon-β1 and ribavirin have shown greater effects in inhibiting coronavirus replication as compared to LPV or RTV alone [140][59]. Due to the lack of efficacy and increased incidence of adverse events, the clinical use of LPV/r in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was not recommended [141][60].

Umifenovir (Arbidol), also known as ARB, is an antiviral drug that can inhibit several DNA and RNA viruses, including the West Nile virus, Zika virus, and hepatitis C virus. Simulations showed that umifenovir inserts into the spike protein of the virus, blocking viral fusion to the cell [142][61]. Reaching phase IV of clinical trials, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and ACE inhibitors have been used to help in treating moderate to severe infections in patients with pneumonia [143][62]. Another study showed that ARB combined with LPV/r was better than lopinavir alone [144][63]. However, arbidol has shown little to no effect on patients with mild or moderate symptoms of COVID-19 [145,146][64][65].

Favipiravir (Avigan/T-705) is a pyridinecarboxamide that was initially developed as an anti-influenza substance and is classified as an antiviral drug that selectively inhibits the RNA polymerase of RNA viruses [147][66]. Favipiravir was shown to be effective against the influenza strains A(H1N1) and A(H7N9), and it later was used as a potential treatment for the Ebola virus, West Nile viruses, arenaviruses, and other viruses [148][67]. Once inside the cell, favipiravir is ribosylated and phosphorylated into its active form, T-705RTP [149][68]. Enzyme kinetic analysis demonstrated that T-705RTP inhibited the incorporation of ATP and GTP in a competitive manner, preventing the strand extension of the virus [150][69]. Initial trials for use in response to COVID-19 suggested that favipiravir administration in individuals with mild to moderate infection has a strong potential to improve clinical outcomes [151][70]. However, recent studies showed that favipiravir does not improve clinical response in all COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, and further high-quality studies of antiviral agents and their potential treatment combinations are warranted [152][71].

Gemcitabine (Gemzar): Gemcitabine hydrochloride is a pyrimidine nucleoside analog that is commonly used as a chemotherapeutic agent against several forms of cancer, such as pancreatic cancer [153][72]. Previous investigations of the effect of gemcitabine on MERS and SARS reported that the drug inhibits both HCoVs at a low micromolar EC50 of 1.22 and 4.96 μM, respectively [154][73]. One report suggested that the difluoro group of gemcitabine is critical to its antiviral activity and could be a desirable option to treat SARS-CoV-2 in combination with other antiviral drugs, such as remdesivir [155][74].

Nafamostat Mesylate (Fusan) is a broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor that can act as an anticoagulant and is used to treat pancreatitis and other inflammatory diseases [156][75]. In 2016, nafamostat mesylate was identified as a treatment option for MERS, successfully inhibiting the host cell’s TMPRSS2 receptor during viral S protein–cell membrane fusion, setting it up for potential inhibition of other HCoVs [113][31]. In April 2020, when comparing serine protease inhibitors, one study showed that nafamostat mesylate had a 15-fold increase when compared with camostat mesylate in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 S protein fusion mediated by the host cell ACE2/TMPRSS2 receptor complex [157][76]. Moreover, a case study reported the efficiency of both favipiravir and nafamostat mesylate as a joint treatment in SARS-CoV-2 patients, noting that the anti-blood clotting properties of nafamostat mesylate were likely beneficial in treating SARS-CoV-2 patients [158][77]. Additional clinical trials are needed to provide more robust data on the safety and efficacy of nafamostat as a treatment for COVID-19 [159][78].

Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir: Both drugs are classified as direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) and are FDA-approved to treat the hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to their combined ability to inhibit the functions of HCV nonstructural protein 5 (NS5B), an essential component in viral replication [160][79]. Like HCV, SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-stranded RNA virus, making it the potential primary target of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir [161][80]. However, no significant reduction in the SARS-CoV-2 viral load was observed in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and receiving this treatment plan when compared with a control group [162][81]. Larger clinical trials are warranted.

EIDD-2801 (molnupiravir) is an orally bioavailable ribonucleoside analog of β-D-N4-hydroxycytidine (NHC, EIDD-1931) [163][82]. NHC has been found to participate in viral replication by causing mutations from G to A and C to U, which is deadly to the new replication of the virus [164][83]. Studies have shown that EIDD-2801 is highly effective against SARS-CoV in Vero cells (IC50 of 0.3 µM) and in mice infected with MERS, and it was also effective against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp mutations that developed as a result of remdesivir treatment [165][84]. In November 2021, the U.K. became the first country to approve this drug for the treatment against mild and moderate SARS-CoV-2. Within a month, the U.S. FDA approved EIDD-2801 for emergency use [166][85]. EIDD-2801 is the first oral antiviral drug that demonstrated efficacy in decreasing the viral RNA amounts in nasopharyngeal swabs [167][86]. Relatedly, recent studies provide evidence of the efficacy of molnupiravir, which compliments the ongoing clinical trials of EIDD-2801 [168][87].

Galidesivir (BCX4430) is an adenosine nucleoside analog shown to have effective antiviral properties against several RNA viruses, including the Zika virus, HCV, and Ebola virus [169][88]. Two studies showed that galidesivir has an ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and thus has potential as a therapeutic agent [170,171][89][90]. In cells where phosphorylation occurs, premature chain termination can be achieved. Structural modeling shows a potential allosteric inhibition of RdRp as galidesivir binds to the noncatalytic site of the enzyme [172][91]; however, early stages of clinical trials showed no benefit for COVID-19 patients [173][92].

3.1.3. Other Agents and Therapies

Vitamin C: Studies have shown that intravenous (IV) vitamin C may help COVID-19 patients by reducing inflammation or possibly by restoring the antioxidant protection of the body [174][93]. Overall, evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests a survival benefit for vitamin C in patients with severe COVID-19; however, more data with definitive outcomes are needed before it is recommended to provide high-dose vitamin C therapy to prevent or treat COVID-19 [175][94]. It is currently advised to maintain a normal physiologic range of plasma vitamin C through diet or supplements for adequate prophylactic protection against the virus [176][95].

Corticosteroids are synthetic analogs of steroid hormones naturally produced by the adrenal cortex that have broad anti-inflammatory activities [177][96]. Dexamethasone is a fluorinated corticosteroid that relieves inflammation and is commonly used to treat arthritis [178][97]. In a clinical trial of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the use of dexamethasone resulted in lower mortality among those receiving either mechanical ventilation or oxygen [179][98].

Bamlanivimab and etesevimab are monoclonal antibodies that target the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and thus prevent the entry of the virus into human cells [182][99]. Identifying the specific antibodies from a patient that recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection expedited the development of this treatment in eight months [183][100].

3.1.4. Antibiotic/Antibacterial

Azithromycin (AZM) is a macrolide antibiotic that has been approved by the FDA to treat enteric and respiratory tract bacterial infections. It was investigated in combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) to treat hospitalized COVID-19 patients with bacterial infections [187][101]. A clinical trial of HCQ and AZM consisting of 504 COVID-19 patients randomized at a 1:1:1 ratio compared the outcomes of one group receiving standard care, another group treated only with HCQ, and the third group receiving an AZM/HCQ mixture. The results showed that the use of HCQ with or without AZM did not improve clinical status at 15 days when compared to the standard care treatment [188][102]. Several other studies with AZM as a therapy showed no increase in clinical benefit and that there was potential risk for development of antibacterial resistance [189][103]. The results from the COALITION II Trial, RECOVERY Trial, and PRINCIPLE trial showed that AZM was not better than standard care alone and did not provide any benefits in recovery. Following these findings, the NIH and WHO recommended against the use of antibacterial medicine for COVID-19 patients [190][104].

Cefuroxime, a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is commonly used in the treatment of respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections, has been investigated as anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent [191][105]. In silico studies reported the antibiotic as a strong inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2’s major protease [192,193,194][106][107][108]. As such, these in silico studies showed that cefuroxime could potentially be successful in clinical trials due to its bioavailability and viral inhibitory activity. However, the gratuitous use of antibiotics for COVID-19 treatment without proper clinical rationale raised concerns about the global problem of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [195][109].

Teicoplanin is a glycopeptide antibiotic used to treat Gram-positive bacterial infections [196][110] that has been of interest in the drug-repurposing efforts against SARS-CoV-2. Teicoplanin and its derivatives were shown to inhibit cathepsin L activity in Ebola, SARS, and MERS infections. Teicoplanin does not block cellular viral receptors or target viral particles, but its inhibitory action against cathepsin L leads to reduced low-pH-associated cleavage of the SARS-CoV S protein, preventing the S glycoprotein trimer from fusing with the host cell membrane [197][111].

3.1.5. ACE2 Inhibitors

Captopril, a high blood pressure medication primarily marketed for patients affected by diabetes, congestive heart failure, or hypertension [200][112], was selected as a potential treatment against SARS-CoV-2 infection due to its angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory action [201][113]. Experimental data suggested that captopril increased the level of ACE2 expression in lung cells, and this up-regulation was counteracted by drug-induced mechanisms that reduced SARS-CoV-2 spike protein entry [202][114]. The ACE2-centered therapeutic approaches to prevent and treat COVID-19 now need to be tested in clinical trials to combat current cases of COVID-19, including all SARS-CoV-2 variants and other emerging zoonotic coronaviruses exploiting ACE2 as their cellular receptor [203][115].

hrsACE2/rhACE2c: Human recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2) is a novel compound listed for clinical trials to test its efficacy in regulating a patient’s imbalance in the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) [204][116]. While one report that hrsACE2 successfully prevented SARS-CoV-2 entry and decreased viral RNA levels suggests that hrsACE2 might provide an effective SARS-CoV-2 treatment, further clinical trial data are needed to validate this finding [205][117].

Ramipril is an antihypertensive drug that has been considered as a potential treatment against SARS-CoV-2 [206][118]. Ramipril works by preventing counter-regulatory ACE from cleaving decapeptide angiotensin I into angiotensin II. Angiotensin II plays an important role in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), which regulates blood pressure, vasoconstriction, and extracellular volume [207][119]. Assessment of hypertensive drugs has been conducted extensively, and guidance for the use of ACE and ARBs (hypertensive drugs that operate in the same biochemical pathway as ACE2, i.e., the RAAS system) suggested that the use of ACEIs/ARBs did not significantly influence either mortality or severity in comparison to not taking ACEIs/ARBs in COVID-19-positive patients [208,209][120][121].

3.1.6. Anti-Inflammatories

COVID-19 can trigger a cytokine storm through hyperactivation of the immune system and the uncontrolled release of cytokines. This uncontrolled immune response can lead to severe tissue damage and contribute to the progression of the disease. Thus, there has been significant interest in strategies to modulate the immune response in COVID-19 cases, with a focus on suppressing the cytokine storm. This can be achieved through the use of immunomodulatory drugs like corticosteroids or specific drugs that target cytokines or their receptors. However, it is important to note that while these drugs can be effective in managing such conditions, they also suppress the immune system, which can make patients more susceptible to infections. Therefore, patients receiving this medication are typically carefully monitored for signs of infections while on treatment.

Tocilizumab, which is marketed under the brand name Actemra, is an immunosuppressive humanized monoclonal antibody drug. It is used to treat a range of inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [210,211][122][123]. Tocilizumab is the first FDA-approved monoclonal antibody for treating patients with severe COVID-19 [212][124]. It works by targeting and inhibiting the activity of the interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6), a cytokine that plays a key role in various autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [213][125]. By blocking the IL-6 receptor, tocilizumab helps reduce the inflammatory response and can provide relief to patients. Tocilizumab has shown to decrease the duration of hospitalization, the risk of being placed on mechanical ventilation, and the risk of death for patients with severe COVID-19 [214][126].

Anakinra is an immunomodulatory drug that has been studied for its potential to modulate the immune response in COVID-19 cases. It antagonizes inflammation mediated by interleukin-1 (IL-1) via binding to the corresponding receptors, thereby preventing the cascade of sterile inflammation seen in various pathological states. Additionally, anakinra interferes with the assembly of the inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that plays a key role in initiating and regulating the inflammatory response [215][127]. Studies showed that anakinra might be beneficial in the early phase of inflammation in patients at risk for progression to respiratory failure; however, its effectiveness in patients already suffering from respiratory failure is not suggested [216][128]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that anakinra has no effect on adult hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection regarding mortality, clinical improvement, and worsening or on safety outcomes compared to a placebo or standard care alone [217][129].

References

- Malik, Y.S.; Sircar, S.; Bhat, S.; Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Dadar, M.; Tiwari, R.; Chaicumpa, W. Emerging novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)—Current scenario, evolutionary perspective based on genome analysis and recent developments. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 68–76.

- WHO. 2023. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Publishing, Harvard Health. COVID-19 Basics. Harvard Health Last Updated 2021. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-basics (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Cardone, M.; Yano, M.; Rosenberg, A.S.; Puig, M. Lessons Learned to Date on COVID-19 Hyperinflammatory Syndrome: Considerations for Interventions to Mitigate SARS-CoV-2 Viral Infection and Detrimental Hyperinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1131.

- Ilmjärv, S.; Abdul, F.; Acosta-Gutiérrez, S.; Estarellas, C.; Galdadas, I.; Casimir, M.; Alessandrini, M.; Gervasio, F.L.; Krause, K.-H. Concurrent mutations in RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and spike protein emerged as the epidemiologically most successful SARS-CoV-2 variant. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13705.

- Zhou, B.; Thao, T.T.N.; Hoffmann, D.; Taddeo, A.; Ebert, N.; Labroussaa, F.; Pohlmann, A.; King, J.; Steiner, S.; Kelly, J.N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike D614G change enhances replication and transmission. Nature 2021, 592, 122–127.

- Jiang, M.; Kolehmainen, P.; Kakkola, L.; Maljanen, S.; Melén, K.; Smura, T.; Julkunen, I.; Österlund, P. SARS-CoV-2 Isolates Show Impaired Replication in Human Immune Cells but Differential Ability to Replicate and Induce Innate Immunity in Lung Epithelial Cells. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00774-21.

- Laine, L.; Skön, M.; Väisänen, E.; Julkunen, I.; Österlund, P. SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron show a slower host cell interferon response compared to an early pandemic variant. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1016108.

- Belik, M.; Jalkanen, P.; Lundberg, R.; Reinholm, A.; Laine, L.; Väisänen, E.; Skön, M.; Tähtinen, P.A.; Ivaska, L.; Pakkanen, S.H.; et al. Comparative analysis of COVID-19 vaccine responses and third booster dose-induced neutralizing antibodies against Delta and Omicron variants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2476.

- Jalkanen, P.; Kolehmainen, P.; Haveri, A.; Huttunen, M.; Laine, L.; Österlund, P.; Tähtinen, P.A.; Ivaska, L.; Maljanen, S.; Reinholm, A.; et al. Vaccine-Induced Antibody Responses against SARS-CoV-2 Variants-Of-Concern Six Months after the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0225221.

- Ekström, N.; Haveri, A.; Solastie, A.; Virta, C.; Österlund, P.; Nohynek, H.; Nieminen, T.; Ivaska, L.; Tähtinen, P.A.; Lempainen, J.; et al. Strong Neutralizing Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Variants Following a Single Vaccine Dose in Subjects with Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac625.

- Awad, K. COVID-19: End or fade of the pandemic? Lupine Online J. Med. Sci. 2023, 6, 638–639.

- Pandey, A.; Nikam, A.N.; Shreya, A.B.; Mutalik, S.P.; Gopalan, D.; Kulkarni, S.; Padya, B.S.; Fernandes, G.; Mutalik, S.; Prassl, R. Potential therapeutic targets for combating SARS-CoV-2: Drug repurposing, clinical trials and recent advancements. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117883.

- Gorkhali, R.; Koirala, P.; Rijal, S.; Mainali, A.; Baral, A.; Bhattarai, H.K. Structure and Function of Major SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV Proteins. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2021, 15, 11779322211025876.

- Yang, N.; Shen, H.-M. Targeting the Endocytic Pathway and Autophagy Process as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy in COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1724–1731.

- Sriram, K.; Insel, P. What Is the ACE2 Receptor? American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 16 May 2020. Available online: https://www.asbmb.org/asbmb-today/science/051620/what-is-the-ace2-receptor (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 40, 905–919.

- Mahmudpour, M.; Roozbeh, J.; Keshavarz, M.; Farrokhi, S.; Nabipour, I. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The anger of inflammation. Cytokine 2020, 133, 155151.

- Goodman Brenda. Cytokine Storms May Be Fueling Some COVID Deaths. WebMD 2020. Available online: www.webmd.com/lung/news/20200417/cytokine-storms-may-be-fueling-some-covid-deaths (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Katopodis, P.; Randeva, H.S.; Spandidos, D.A.; Saravi, S.; Kyrou, I.; Karteris, E. Host cell entry mediators implicated in the cellular tropism of SARS-CoV-2, the pathophysiology of COVID-19 and the identification of microRNAs that can modulate the expression of these mediators (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 49, 20.

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20.

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.Z.; Swaroop, M.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Lee, J.; Wang, A.Q.; Pradhan, M.; Hagen, N.; Chen, L.; et al. Heparan sulfate assists SARS-CoV-2 in cell entry and can be targeted by approved drugs in vitro. Cell Discov. 2021, 6, 80.

- Pruimboom, L. SARS-CoV 2; Possible alternative virus receptors and pathophysiological determinants. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 146, 110368.

- Awad, K.; Maghraby, A.S.; Abd-Elshafy, D.N.; Bahgat, M.M. Carbohydrates Metabolic Signatures in Immune Cells: Response to Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 912899.

- Felsenstein, S.; Herbert, J.A.; McNamara, P.S.; Hedrich, C.M. COVID-19: Immunology and treatment options. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 215, 108448.

- Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Network, H.L. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Genes Are Most Highly Expressed in Nasal Goblet and Ciliated Cells within Human Airways. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.06122v1.

- Xu, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Peng, J.; Dan, H.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Chen, Q. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 8.

- Tian, L.; Qiang, T.; Liang, C.; Ren, X.; Jia, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Wan, M.; Wen, X.Y.; Li, H.; et al. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors: The current landscape and repurposing for the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 213, 113201.

- Ianevski, A.; Zusinaite, E.; Kuivanen, S.; Strand, M.; Lysvand, H.; Teppor, M.; Kakkola, L.; Paavilainen, H.; Laajala, M.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; et al. Novel activities of safe-in-human broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 174–182.

- Kumar, D.; Trivedi, N. Disease-drug and drug-drug interaction in COVID-19: Risk and assessment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111642.

- Identification of an Existing Japanese Pancreatitis Drug, Nafamostat, Which Is Expected to Prevent the Transmission of New Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19). The University of Tokyo. 2020. Available online: https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/focus/en/articles/z0508_00083.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Li, K.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Bartlett, J.A.; McCray, P.B. The TMPRSS2 Inhibitor Nafamostat Reduces SARS-CoV-2 Pulmonary Infection in Mouse Models of COVID-19. Mbio 2021, 12, e0097021.

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and Chloroquine Effectively Inhibit the Recently Emerged Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) In Vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271.

- Christian, A.; Rolain, R.; Colson, P.; Raoult, D. New Insights on the Antiviral Effects of Chloroquine against Coronavirus: What to Expect for COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105938.

- Ou, T.; Mou, H.; Zhang, L.; Ojha, A.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. Hydroxychloroquine-mediated inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry is attenuated by TMPRSS2. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009212.

- Goldman, F.D.; Gilman, A.L.; Hollenback, C.; Kato, R.M.; Premack, B.A.; Rawlings, D.J. Hydroxychloroquine Inhibits Calcium Signals in T Cells: A New Mechanism to Explain Its Immunomodulatory Properties. Blood, Content Repository Only! 14 December 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006497120640113?via%3Dihub (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Revokes Emergency Use Authorization for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. US FDA 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-chloroquine-and (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Pardo, J.; Shukla, A.M.; Chamarthi, G.; Gupte, A. The journey of remdesivir: From Ebola to COVID-19. Drugs Context 2020, 9, 1–9.

- Remdesivir-List Results. Home-Clinical Trials.gov 2020. Available online: Clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=remedesivir (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Dangerfield, T.L.; Huang, N.Z.; Johnson, K.A. Remdesivir Is Effective in Combating COVID-19 because It Is a Better Substrate than ATP for the Viral RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. iScience 2020, 23, 101849.

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.C.; Hui, D.S.; Marks, K.M.; Bruno, R.; Montejano, R.; Spinner, C.D.; Galli, M.; Ahn, M.-Y.; Nahass, R.G.; et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1827–1837.

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19—Final Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826.

- Yousefi, B.; Valizadeh, S.; Ghaffari, H.; Vahedi, A.; Karbalaei, M.; Eslami, M. A global treatments for coronaviruses including COVID-19. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 9133–9142.

- Martinez, M.A. Compounds with Therapeutic Potential against Novel Respiratory 2019 Coronavirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00399-20.

- Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Hung, I.F.N.; Wong, M.M.L.; Chan, K.H.; Chan, K.S.; Kao, R.Y.T.; Poon, L.L.M.; Wong, C.L.P.; Guan, Y.; et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax 2004, 59, 252–256.

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Momattin, H.; Dib, J.; Memish, Z.A. Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: An observational study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 42–46.

- Hung, I.F.-N.; Lung, K.-C.; Tso, E.Y.-K.; Liu, R.; Chung, T.W.-H.; Chu, M.-Y.; Ng, Y.-Y.; Lo, J.; Chan, J.; Tam, A.R.; et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: An open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1695–1704.

- Information on COVID-19 Treatment, Prevention and Research. NIH US 2021. Available online: www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Sallard, E.; Lescure, F.-X.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Mentre, F.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Type 1 interferons as a potential treatment against COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104791.

- Cinatl, J.; Morgenstern, B.; Bauer, G.; Chandra, P.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet 2003, 362, 293–294.

- Falzarano, D.; de Wit, E.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Feldmann, F.; Okumura, A.; Scott, D.P.; Brining, D.; Bushmaker, T.; Martellaro, C.; Baseler, L.; et al. Treatment with interferon-α2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV–infected rhesus macaques. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1313–1317.

- Chan, J.F.; Chan, K.-H.; Kao, R.Y.; To, K.K.; Zheng, B.-J.; Li, C.P.; Li, P.T.; Dai, J.; Mok, F.K.; Chen, H.; et al. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. 2013, 67, 606–616.

- Kalil, A.C.; Mehta, A.K.; Patterson, T.F.; Erdmann, N.; Gomez, C.A.; Jain, M.K.; Wolfe, C.R.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Kline, S.; Pineda, J.R.; et al. Efficacy of interferon beta-1a plus remdesivir compared with remdesivir alone in hospitalised adults with COVID-19: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1365–1376.

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium; Pan, H.; Peto, R.; Henao-Restrepo, A.M.; Preziosi, M.P.; Sathiyamoorthy, V. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for COVID-19—Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 497–511.

- Wang, B.; Li, D.; Liu, T.; Wang, H.; Luo, F.; Liu, Y. Subcutaneous injection of IFN alpha-2b for COVID-19: An observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 723.

- Pandit, A.; Bhalani, N.; Bhushan, B.S.; Koradia, P.; Gargiya, S.; Bhomia, V.; Kansagra, K. Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2b in moderate COVID-19: A phase II, randomized, controlled, open-label study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 516–521.

- Yao, T.; Qian, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. A systematic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus—A possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 556–563.

- Srivastava, K.; Singh, M.K. Drug repurposing in COVID-19: A review with past, present and future. Metab. Open 2021, 12, 100121.

- Neil, O. Triple Antiviral Combo May Speed COVID-19 Recovery. Medscape. 2020. Available online: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/930336 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Heybati, K.; Ali, S.; Chang, O.; Silver, Z.; Dhivagaran, T.; Ramaraju, H.B.; Wong, C.Y.; et al. Efficacy of lopinavir–ritonavir combination therapy for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Future Virol. 2022, 17, 169–189.

- Leneva, I.; Kartashova, N.; Poromov, A.; Gracheva, A.; Korchevaya, E.; Glubokova, E.; Borisova, O.; Shtro, A.; Loginova, S.; Shchukina, V.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Umifenovir In Vitro against a Broad Spectrum of Coronaviruses, Including the Novel SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1665.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) ACEi/ARB Investigation. NIH 2020. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04330300 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Deng, L.; Li, C.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Hong, Z.; Xia, J. Arbidol combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r alone against Corona Virus Disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e1–e5.

- Li, Y.; Xie, Z.; Lin, W.; Cai, W.; Wen, C.; Guan, Y.; Mo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Peng, P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lopinavir/Ritonavir or Arbidol in Adult Patients with Mild/Moderate COVID-19: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Med 2020, 1, 105–113.e4.

- Trivedi, N.; Verma, A.; Kumar, D. Possible treatment and strategies for COVID-19: Review and assessment. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 12593–12608.

- Furuta, Y.; Gowen, B.B.; Takahashi, K.; Shiraki, K.; Smee, D.F.; Barnard, D.L. Favipiravir (T-705), a novel viral RNA polymerase inhibitor. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 446–454.

- Shiraki, K.; Daikoku, T. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 209, 107512.

- Madelain, V.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Olivo, A.; de Lamballerie, X.; Guedj, J.; Taburet, A.-M.; Mentré, F. Ebola Virus Infection: Review of the Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Drugs Considered for Testing in Human Efficacy Trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2016, 55, 907–923.

- Sangawa, H.; Komeno, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Yoshida, A.; Takahashi, K.; Nomura, N.; Furuta, Y. Mechanism of Action of T-705 Ribosyl Triphosphate against Influenza Virus RNA Polymerase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5202–5208.

- Srinivasan, K.; Rao, M. Understanding the clinical utility of favipiravir (T-705) in coronavirus disease of 2019: A review. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 2049936121106301.

- Shah, P.L.; Orton, C.M.; Grinsztejn, B.; Donaldson, G.C.; Ramírez, B.C.; Tonkin, J.; Santos, B.R.; Cardoso, S.W.; Ritchie, A.I.; Conway, F.; et al. Favipiravir in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (PIONEER trial): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial of early intervention versus standard care. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 415–424.

- Zhang, Y.-N.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Li, X.-D.; Xiong, J.; Xiao, S.-Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Deng, C.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Wei, H.-P.; et al. Gemcitabine, Lycorine and Oxysophoridine Inhibit Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Cell Culture. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1170–1173.

- Gemcitabine Hydrochloride for the Treatment of SARS-CoV-2—Creative Biolabs. Creative BioLabs 2020. Available online: sars-cov-2.creative-biolabs.com/gemcitabine-hydrochloride-for-the-treatment-of-sars-cov2.htm (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Jang, Y.; Shin, J.S.; Lee, M.K.; Jung, E.; An, T.; Kim, U.-I.; Kim, K.; Kim, M. Comparison of Antiviral Activity of Gemcitabine with 2′-Fluoro-2′-Deoxycytidine and Combination Therapy with Remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1581.

- Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Zeng, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Qian, L.; Wei, J.; Yang, X.; Shen, Q.; Gong, Z.; et al. The Molecular Aspect of Antitumor Effects of Protease Inhibitor Nafamostat Mesylate and Its Role in Potential Clinical Applications. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 852.

- Hoffmann, M.; Schroeder, S.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Müller, M.A.; Drosten, C.; Pöhlmann, S. Nafamostat Mesylate Blocks Activation of SARS-CoV-2: New Treatment Option for COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00754-20.

- Doi, K.; the COVID-UTH Study Group; Ikeda, M.; Hayase, N.; Moriya, K.; Morimura, N. Nafamostat Mesylate Treatment in Combination with Favipiravir for Patients Critically Ill with COVID-19: A Case Series. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 392.

- Hernández-Mitre, M.P.; Tong, S.Y.C.; Denholm, J.T.; Dore, G.J.; Bowen, A.C.; Lewin, S.R.; Venkatesh, B.; Hills, T.E.; McQuilten, Z.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Nafamostat Mesylate for Treatment of COVID-19 in Hospitalised Patients: A Structured, Narrative Review. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 1331–1343.

- Wang, X.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Jockusch, S.; Chaves, O.A.; Tao, C.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Chien, M.; Temerozo, J.R.; Li, X.; Kumar, S.; et al. Combination of antiviral drugs inhibits SARS-CoV-2 polymerase and exonuclease and demonstrates COVID-19 therapeutic potential in viral cell culture. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 154.

- Shabani, M.; Ehdaei, B.S.; Fathi, F.; Dowran, R. A mini-review on sofosbuvir and daclatasvir treatment in coronavirus disease 2019. New Microbes New Infect. 2021, 42, 100895.

- Maia, I.S.; Marcadenti, A.; Veiga, V.C.; Miranda, T.A.; Gomes, S.P.; Carollo, M.B.; Negrelli, K.L.; Gomes, J.O.; Tramujas, L.; Abreu-Silva, E.O.; et al. Antivirals for adult patients hospitalised with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A randomised, phase II/III, multicentre, placebo-controlled, adaptive study, with multiple arms and stages. COALITION COVID-19 BRAZIL IX—REVOLUTIOn trial. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 20, 100466.

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Zhou, S.; Graham, R.L.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Agostini, M.L.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An orally bioavailable broad-spectrum antiviral inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cell cultures and multiple coronaviruses in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabb5883.

- Tian, L.; Pang, Z.; Li, M.; Lou, F.; An, X.; Zhu, S.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H.; Fan, J. Molnupiravir and Its Antiviral Activity Against COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 855496.

- Agostini, M.L.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Chappell, J.D.; Gribble, J.; Lu, X.; Andres, E.L.; Bluemling, G.R.; Lockwood, M.A.; Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; et al. Small-Molecule Antiviral β-d-N4-Hydroxycytidine Inhibits a Proofreading-Intact Coronavirus with a High Genetic Barrier to Resistance. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01348-19.

- Victor, A. Bringing the Fight to COVID-19 with Accelerated Clinical Trials of Merck’s Molnupiravir. Insights From Our Labs to Yours, 9 December 2021. Available online: https://ddblog.labcorp.com/2021/12/bringing-the-fight-to-covid-19-with-accelerated-clinical-trials-of-mercks-molnupiravir/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Fischer, W.; Eron, J.J.; Holman, W.; Cohen, M.S.; Fang, L.; Szewczyk, L.J.; Sheahan, T.P.; Baric, R.; Mollan, K.R.; Wolfe, C.R.; et al. A phase 2a clinical trial of molnupiravir in patients with COVID-19 shows accelerated SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance and elimination of infectious virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabl7430.

- Johnson, D.M.; Brasel, T.; Massey, S.; Garron, T.; Grimes, M.; Smith, J.; Torres, M.; Wallace, S.; Villasante-Tezanos, A.; Beasley, D.W.; et al. Evaluation of molnupiravir (EIDD-2801) efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in the rhesus macaque model. Antivir. Res. 2023, 209, 105492.

- Taylor, R.; Kotian, P.; Warren, T.; Panchal, R.; Bavari, S.; Julander, J.; Dobo, S.; Rose, A.; El-Kattan, Y.; Taubenheim, B.; et al. BCX4430—A broad-spectrum antiviral adenosine nucleoside analog under development for the treatment of Ebola virus disease. J. Infect. Public Health 2016, 9, 220–226.

- Elfiky, A.A. Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): A molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020, 253, 117592.

- Julander, J.G.; Demarest, J.F.; Taylor, R.; Gowen, B.B.; Walling, D.M.; Mathis, A.; Babu, Y. An update on the progress of galidesivir (BCX4430), a broad-spectrum antiviral. Antivir. Res. 2021, 195, 105180.

- Mei, M.; Tan, X. Current Strategies of Antiviral Drug Discovery for COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 671263.

- BioCryst Stops COVID-19 Work to Target Other Viral R&D. NC Biotech. 28 December 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbiotech.org/news/biocryst-stops-covid-19-work-target-other-viral-rd (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Is IV Vitamin C Effective against COVID-19? Linus Pauling Institute 2020. Available online: lpi.oregonstate.edu/COVID19/IV-VitaminC-virus (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Ramachandram, D.S. The effect of vitamin C on the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 1–6, Epub ahead of print.

- Moore, A.; Khanna, D. The Role of Vitamin C in Human Immunity and Its Treatment Potential Against COVID-19: A Review Article. Cureus 2023, 15, e33740.

- Liu, D.; Ahmet, A.; Ward, L.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Mandelcorn, E.D.; Leigh, R.; Brown, J.P.; Cohen, A.; Kim, H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, 30.

- Dexamethasone: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Medline Plus US National Library of Medicine 2021. Available online: medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a682792.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704.

- Lilly Earns First Authorization for Novel Antibody Therapy for COVID-19. c&en 2021. Available online: https://cen.acs.org/pharmaceuticals/biologics/Lilly-earns-first-authorization-novel/98/i44 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Dougan, M.; Nirula, A.; Azizad, M.; Mocherla, B.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Chen, P.; Hebert, C.; Perry, R.; Boscia, J.; Heller, B.; et al. Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab in Mild or Moderate COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1382–1392.

- Azithromycin: Medline Plus Drug Information. Medline Plus US National Library of Medicine. 2021. Available online: medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697037.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Cavalcanti, A.B.; Zampieri, F.G.; Rosa, R.G.; Azevedo, L.C.; Veiga, V.C.; Avezum, A.; Damiani, L.P.; Marcadenti, A.; Kawano-Dourado, L.; Lisboa, T.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without Azithromycin in Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2041–2052.

- Kamel, A.M.; Monem, M.S.A.; Sharaf, N.A.; Magdy, N.; Farid, S.F. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2258.

- What Antibiotics Kill COVID-19 (Coronavirus)? Drugs.com. 1 December 2021. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/medical-answers/antibiotics-kill-coronavirus-3534867/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Durojaiye, A.B.; Clarke, J.-R.D.; Stamatiades, G.A.; Wang, C. Repurposing cefuroxime for treatment of COVID-19: A scoping review of in silico studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 4547–4554.

- Al-Khafaji, K.; AL-DuhaidahawiL, D.; Tok, T.T. Using integrated computational approaches to identify safe and rapid treatment for SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 3387–3395.

- Banerjee, R.; Perera, L.; Tillekeratne, L.V. Potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 804–816.

- Koulgi, S.; Jani, V.; Uppuladinne, M.; Sonavane, U.; Nath, A.K.; Darbari, H.; Joshi, R. Drug repurposing studies targeting SARS-CoV-2: An ensemble docking approach on drug target 3C-like protease (3CLpro). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 5735–5755.

- Malik, S.S.; Mundra, S. Increasing Consumption of Antibiotics during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Patient Health and Emerging Anti-Microbial Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 45.

- Zhou, L.; Gao, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, J.; Guan, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Lv, W.; Cheng, L. Retrospective analysis of relationships among the dose regimen, trough concentration, efficacy, and safety of teicoplanin in Chinese patients with moder-ate-severe Gram-positive infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 29–36.

- Zhou, N.; Pan, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Bai, C.; Huang, F.; Peng, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Glycopeptide Antibiotics Potently Inhibit Cathepsin L in the Late Endosome/Lysosome and Block the Entry of Ebola Virus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV). J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9218–9232.

- Sharif-Askari, N.S.; Sharif-Askari, F.S.; Al Heialy, S.; Hamoudi, R.; Kashour, T.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R. Cardiovascular medi-cations and regulation of COVID-19 receptors expression. Int. J. Cardiol. Hypertens. 2020, 6, 100034.

- Biyani, C.S.; Palit, V.; Daga, S. The Use of Captopril—Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor for Cystinuria During COVID-19 Pandemic. Urology 2020, 141, 182–183.

- Pedrosa, M.A.; Valenzuela, R.; Garrido-Gil, P.; Labandeira, C.M.; Navarro, G.; Franco, R.; Labandeira-Garcia, J.L.; Rodriguez-Perez, A.I. Experimental data using candesartan and captopril indicate no double-edged sword effect in COVID-19. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 465–481.

- Oudit, G.Y.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Kellner, M.J.; Penninger, J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2—At the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell 2023, 186, 906–922.

- Monteil, V.; Kwon, H.; Prado, P.; Hagelkrüys, A.; Wimmer, R.A.; Stahl, M.; Leopoldi, A.; Garreta, E.; Del Pozo, C.H.; Prosper, F.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Engineered Human Tissues Using Clinical-Grade Soluble Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 905–913.e7.

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Zhong, J.C.; Turner, A.J.; Raizada, M.K.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angioten-sin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474.

- Ajmera, V.; Thompson, W.K.; Smith, D.M.; Malhotra, A.; Mehta, R.L.; Tolia, V.; Yin, J.; Sriram, K.; Insel, P.A.; Collier, S.; et al. RAMIC: Design of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of ramipril in patients with COVID-19. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 103, 106330.

- Chauhan, M.; Patel, J.; Ahmad, F. Ramipril . Treasure Island 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537119/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Singh, R.; Rathore, S.S.; Khan, H.; Bhurwal, A.; Sheraton, M.; Ghosh, P.; Anand, S.; Makadia, J.; Ayesha, F.; Mahapure, K.S.; et al. Mortality and Severity in COVID-19 Patients on ACEIs and ARBs—A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 703661.

- Nakhaie, S.; Yazdani, R.; Shakibi, M.; Torabian, S.; Pezeshki, S.; Bazrafshani, M.S.; Azimi, M.; Salajegheh, F. The effects of antihypertensive medications on severity and outcomes of hypertensive patients with COVID-19. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 37, 1–8.

- Song, S.-N.J.; Yoshizaki, K. Tocilizumab for treating rheumatoid arthritis: An evaluation of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and clinical efficacy. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 307–316.

- Xu, X.; Han, M.; Li, T.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Fu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Effective Treatment of Severe COVID-19 Patients with Tocilizumab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10970–10975.

- FDA Approves Genentech’s Actemra for the Treatment of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Adults. Business Wire. News Release. 21 December 2022. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20221221005002/en (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Montazersaheb, S.; Khatibi, S.M.H.; Hejazi, M.S.; Tarhriz, V.; Farjami, A.; Sorbeni, F.G.; Farahzadi, R.; Ghasemnejad, T. COVID-19 infection: An overview on cytokine storm and related interventions. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 92.

- Kyriakopoulos, C.; Ntritsos, G.; Gogali, A.; Milionis, H.; Evangelou, E.; Kostikas, K. Tocilizumab administration for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology 2021, 26, 1027–1040.

- Baskar, S.; Klein, A.L.; Zeft, A. The Use of IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (Anakinra) in Idiopathic Recurrent Pericarditis: A Narrative Review. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 7840724.

- Khani, E.; Shahrabi, M.; Rezaei, H.; Pourkarim, F.; Afsharirad, H.; Solduzian, M. Current evidence on the use of anakinra in COVID-19. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109075.

- Dahms, K.; Mikolajewska, A.; Ansems, K.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Benstoem, C.; Stegemann, M. Anakinra for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 100.

More