The screening of rare plants from the Yucatan region and the known native plants in Mexico, that have been successfully introduced worldwide, has been conducted. The preservation of traditional medicinal knowledge in Mayan culture, especially concerning pharmacologically significant plants, can be inferred from the recognition of useful plant species used in previous centuries. Focusing on the antioxidant properties of underutilized and rare plants is especially relevant in the context of Mayan-origin biodiversity. These plants are fundamental to the Mayan diet and traditional medicine and represent an invaluable genetic resource that could be at risk due to climate change and biodiversity loss. Moreover, identifying the specific secondary metabolites associated with the antioxidant potential of these plants could offer new avenues for drug and therapy development.

- antioxidant propertie

- Mayan

- plants

1. Introduction

2. Plants and Plant-Derived Compounds with Antioxidant Potential from Mayan Region

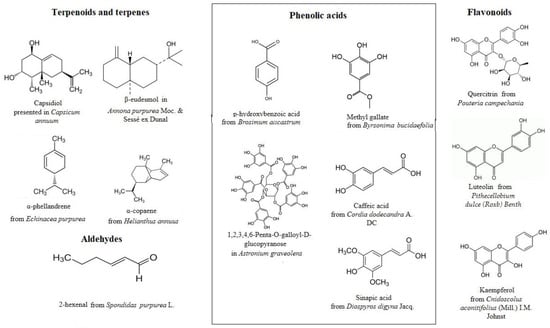

| Plant Species | Family | Plant Part | Terpenes Terpenoids |

Phenolic Acids | Alkaloids | Flavonoids Flavones |

Coumarins | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achras sapota (Sapodilla) |

Sapidaceae | stem, leaves, fruit | present (not specified) | present (not specified) | present (not specified) | dihydromyricetin, quercitrin, myricitrin, catechin, epicatechin, gallocatechin |

present (not specified) | [16,17,18,19][14][15][16][17] |

| Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal (Sancoya) | Annonaceae | leaves, pulp, seeds | β-eudesmol, α-eudesmol |

present (not specified) | Norpurpureine 7-formyl-dehydrothalicsimidine 8-7-hydroxy-dehydrothalicsimidine N-methyllaurotetanine N-methylasimilobine Lirinidine Thalicsimidine Purpureine 3-hydroxyglaucine Annomontine Annopurpuricins A-D |

present (not specified) | present (not specified) | [20,21,22][18][19][20] |

| Astronium graveolens (Gateado) | Anacardiaceae | leaves | lupeol | 3-O-caffeoylquinic, 5-sinapoylquinic, 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-D-glucopyranose | quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside | - | [23][21] | |

| Brosimum alicastrum swartz (Ramon) | Moraceae | leaves, seeds, bark |

- | Gallic, chloro genic, vanillic, sinapic, ferulic, t-cinnamic, coumaric, caffeic acid, p-hydroxibenzoic, m-hydroxybenzoic acids | - | Quercetin, catechin, epicatechin, catechin gallate, syringetin, Kaempferol−O−dihexoside, Isoquercetin | Xanthyletin, luvangetin, 8-hydroxyxanthyletin | [24,25,26][22][23][24] |

| Byrsonima bucidaefolia (Sak Pah) |

Malpighiaceae | leaves | - | Methyl gallate, methyl-m-trigallate | - | - | - | [27][25] |

| Capsicum annuum (Bell pepper) |

Solanaceae | fruit | capsidiol | cinnamic acid | capsaicinoids | quercetin, luteolin, caffeoyl, cinnamoyl glycosides, apigenin |

coumaric acid coumaroyl |

[28,29,30][26][27][28] |

| Cnidosfolus aconitifolius IM. Jonst (Chaya) |

leaves | α y β amyrin, borneol, hederaginin, oleanolic acid, squalene, lupeol acetate | ellagic, ferulic, p-coumaric, caffeic, protocacheuic, vainillic, chlorogenic, caftaric, p-hidroxibenzoico, coutaric, syringic, synaptic acids | choline, trigonelline, nicotinic acid, palmatine, sitsirikine, Dihydrositsirikine, vinblastine, vindoline, catharanthine, vinleurosine | kaempferol, quercetin, rutin, catechin, hesperidin, narigenin, kaempferol, procuanidin B1, catechin, procyanidin B2, rutin, gallocatechin gallate, epigallocatechin gallate, epicatechin-3-O-gallate, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-glycoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, trans-resveratrol | - | [31,32,33,34][29][30][31][32] | |

| Cordia dodecandra DC. (Circote) | Sapidaceae | fruit | - | caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, caffeoyl hexoside | - | Rutin, Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside, lutein | - | [35,36,37][33][34][35] |

| Diospyros digyna Jacq. (Black sapote) | Ebenaceae | fruit, pulp, peel, seeds |

- | Cinnamic, p-hydroxybenzoic, Caffeic, Sinapic, Ferulic, O-Coumaric, Protocatechuic, Chlorogenic, Isochlorogenic |

- | Catechin Epicatechin Myricetin Gallocatechol Epigallocatechin, rutin, Myricetrin, Isohermetin, Kaempherol-4′-glucoside, Quercetin, Dihydromyricetin, Cynaroside |

- | [38,39][36][37] |

| Echinacea purpurea (Purple coneflower) |

Asteraceae | whole plant | α-phellandrene, camphene, limonene | present (not specified) | pyrrolizidine alkaloids tussilagine and isotussilagine | quercetin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin | Coumaric acid | [40,42,43,44][41,38][39][40][41][42] |

| Helianthus annuus (Common sunflower) |

Asteraceae | seeds | α-copaene, bornyl acetate, β-elemene, β-selinene, germacrene-D | present (not specified) | present (not specified) | kaempferol, apigenin, dihydroflavonol, daidzein, biochanin A, formononetin, luteolin, quercetin | p-coumaroyl | [45,46,47][43][44][45] |

| Parmentiera aculeata (H.B. & K.) Seeman (Cucumber kat) |

Bignoniaceae | fruit | Lactucin-8-O-methylacrylate | present (not specified) | present (not specified) | - | present (not specified) | [48,49][46][47] |

| Pouteria campechiana (H.B. & K) Baehni (Canisté) |

Sapidaceae | fruit, leaves, seeds, bark | Corsolic acid, euscaphic acid, fatty acid ester of betulinic acid, fatty acid ester of oleanolic acid, maslinic acid, ursolic acid, lucumic acid A, lucimic acid B, 4(R),23-epoxy-2α,3α,19α-trihydroxy-24-norurs-12-en- 28-oic acid, 2α,3α,19α,23-tetrahydroxy-13α,27-cyclours-11-en-28- oic acid, 2α, 3α, 19α, 23 tetrahydroxyursolic acid, 2α,3β,19α-trihydroxy-24-norursa-4(23),12-dien-28-O-ic acid, 3β, 28- dihydroxy-olean-12-enyl fatty acid ester |

Caffeic, ferulic, gallic, protocatechuic, vanillic, p-coumaric acid | - | Apigenin, catechin, epicatechin, gallocatechin, kaempferol, luteolon, myricetin, myricitin, myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside, myricetin-3-O-β-galactoside, quercetin, rutin, myricetin 3-O-α-rhamnopyranoside, quercetin 3-O-α-rhamnopyranoside, quercetin 3-O-β-rhamnopyranoside, quercetin 3-O-β-arabinopyranoside, taxifolin 3-O-arabinofuranoside, taxifolin 3-O-α, rhamnopyranoside | - | [50][48] |

| Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb) Benth (Dziuche) |

Leguminosae | seeds | (−)-19β-D-glucopyranosyl-6,7-dihydroxykaurenoate | Caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, protocatechuic acid, |

- | apigenin, catechin, daidzein, kaemferol, luteolin, quercetin, myricetin, naringin and rutin |

- | [51,52][49][50] |

| Spondias purpurea L. | Anacardiaceae | leaves | spathulenol, linolenic acid, t-caryophyllene, α-muurolene | caffeic acid | - | epigallocatechin | - | [53,54][51][52] |

References

- Goettsch, B.; Urquiza-Haas, T.; Koleff, P.; Acevedo Gasman, F.; Aguilar-Meléndez, A.; Alavez, V.; Alejandre-Iturbide, G.; Aragón Cuevas, F.; Azurdia Pérez, C.; Carr, J.A.; et al. Extinction Risk of Mesoamerican Crop Wild Relatives. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 775–795.

- Castañeda, R.; Cáceres, A.; Velásquez, D.; Rodríguez, C.; Morales, D.; Castillo, A. Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Mayan Medicine for the Treatment of Central Nervous System Disorders: An Overview. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114746.

- Rodríguez-García, C.M.; Ruiz-Ruiz, J.C.; Peraza-Echeverría, L.; Peraza-Sánchez, S.R.; Torres-Tapia, L.W.; Pérez-Brito, D.; Tapia-Tussell, R.; Herrera-Chalé, F.G.; Segura-Campos, M.R.; Quijano-Ramayo, A.; et al. Antioxidant, Antihypertensive, Anti-Hyperglycemic, and Antimicrobial Activity of Aqueous Extracts from Twelve Native Plants of the Yucatan Coast. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213493.

- Lentz, D.L.; Pohl, M.D.L.; Alvarado, J.L.; Tarighat, S.; Bye, R. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) as a Pre-Columbian Domesticate in Mexico. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6232–6237.

- Sytar, O.; Brestic, M.; Hajihashemi, S.; Skalicky, M.; Kubeš, J.; Lamilla-Tamayo, L.; Ibrahimova, U.; Ibadullayeva, S.; Landi, M. COVID-19 Prophylaxis Efforts Based on Natural Antiviral Plant Extracts and Their Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 727.

- Fattori, V.; Hohmann, M.S.; Rossaneis, A.C.; Pinho-Ribeiro, F.A.; Verri, W.A. Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses. Molecules 2016, 21, 844.

- Martínez, E.M.M.; Sandate-Flores, L.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Rostro-Alanis, M.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Underutilized Mexican Plants: Screening of Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Properties of Mexican Cactus Fruit Juices. Plants 2021, 10, 368.

- Soto, K.M.; Pérez Bueno, J.d.J.; Mendoza López, M.L.; Apátiga-Castro, M.; López-Romero, J.M.; Mendoza, S.; Manzano-Ramírez, A. Antioxidants in Traditional Mexican Medicine and Their Applications as Antitumor Treatments. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 482.

- Mendez, M.; Durán, R.; Campos, S.; Dorantes, A. Flora Medicinal. Biodivers. Y Desarro. Hum. En Yucatán 2010, 349–352.

- Türkez, H.; Çelik, K.; Toğar, B. Effects of Copaene, a Tricyclic Sesquiterpene, on Human Lymphocytes Cells in Vitro. Cytotechnology 2014, 66, 597–603.

- Leite, D.O.D.; de F. A. Nonato, C.; Camilo, C.J.; de Carvalho, N.K.G.; da Nobrega, M.G.L.A.; Pereira, R.C.; da Costa, J.G.M. Annona Genus: Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry and Biological Activities. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4056–4091.

- Farhoosh, R.; Johnny, S.; Asnaashari, M.; Molaahmadibahraseman, N.; Sharif, A. Structure–Antioxidant Activity Relationships of o-Hydroxyl, o-Methoxy, and Alkyl Ester Derivatives of p-Hydroxybenzoic Acid. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 128–134.

- Xu, X.; Luo, A.; Lu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Song, H.; Wei, C.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X. P-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Alleviates Inflammatory Responses and Intestinal Mucosal Damage in DSS-Induced Colitis by Activating ERβ Signaling. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104835.

- Punia Bangar, S.; Sharma, N.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, M.; Sandhu, K.S.; Maqsood, S.; Ozogul, F. A Review of Sapodilla (Manilkara zapota) in Human Nutrition, Health, and Industrial Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 319–334.

- Ma, J.; Luo, X.D.; Protiva, P.; Yang, H.; Ma, C.; Basile, M.J.; Weinstein, I.B.; Kennelly, E.J. Bioactive Novel Polyphenols from the Fruit of Manilkara zapota (Sapodilla). J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 983–986.

- Jadhav, S.S.; Swami, S.B.; Pujari, K.H. Study the physico-chemical properties of Sapota (Achras sapota L.). Trends Technol. Sci. Res. 2018, 3, 555605.

- Shanmugapriya, K.; Saravana, P.; Payal, H.; Mohammed, S.P.; Binnie, W. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of Artocarpus Heterophyllus and Manilkara zapota Seeds and Its Reduction Potential. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 3, 256–260.

- Muñoz-Acevedo, A.; Aristizábal-Córdoba, S.; Rodríguez, J.D.; Torres, E.A.; Molina, A.M.; Gutiérrez, R.G.; Kouznetsov, V.V. Citotoxicidad/Capacidad Antiradicalaria in-Vitro y Caracterización Estructural Por GC-MS/1H-13C-RMN de Los Aceites Esenciales de Hojas de Árboles Joven/Adulto de Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé Ex Dunal de Repelón (Atlántico, Colombia). Boletín Latinoam. Y Del Caribe Plantas Med. Y Aromáticas 2016, 15, 99–111.

- Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; de Lourdes Garcia-Magana, M.; Domínguez-Ávila, J.A.; Yahia, E.M.; Salazar-Lopez, N.J.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Montalvo-González, E. Annonas: Underutilized Species as a Potential Source of Bioactive Compounds. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 963–9969.

- Toledo-González, K.A.; Riley-Saldaña, C.A.; Salas-Lizana, R.; De-la-Cruz-Chacón, I.; González-Esquinca, A.R. Alkaloidal Variation in Seedlings of Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé Ex Dunal Infected with Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. and Sacc. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 107, 104611.

- Hernández, V.; Malafronte, N.; Mora, F.; Pesca, M.S.; Aquino, R.P.; Mencherini, T. Antioxidant and Antiangiogenic Activity of Astronium graveolens Jacq. Leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 917–922.

- Barragán-Mendoza, L.; Sotelo-García, D.M.; Via, L.D.; Parra-Delgado, H. Biological Properties of Aqueous Extract and Pyranocoumarins Obtained from the Bark of Brosimum alicastrum Tree. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 290, 115128.

- Moo-Huchin, V.M.; Canto-Pinto, J.C.; Cuevas-Glory, L.F.; Sauri-Duch, E.; Pérez-Pacheco, E.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Effect of Extraction Solvent on the Phenolic Compounds Content and Antioxidant Activity of Ramon Nut (Brosimum alicastrum). Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 1647–1657.

- Pech-Cohuo, S.C.; Martín-López, H.; Uribe-Calderón, J.; González-Canché, N.G.; Salgado-Tránsito, I.; May-Pat, A.; Cue-vas-Bernardino, J.C.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Cervantes-Uc, J.M.; CPacheco, N. Physicochemical, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Bio-Active Films Based on Biological-Chemical Chitosan, a Novel Ramon (Brosimum alicastrum) Starch, and Quercetin. Polymers 2022, 14, 1346.

- Castillo-Avila, G.M.; García-Sosa, K.; Peña-Rodríguez, L.M. Antioxidants from the Leaf Extract of Byrsonima Bucidaefolia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 83–86.

- Howard, L.R.; Wildman, R. Antioxidant Vitamin and Phytochemical Content of Fresh and Processed Pepper Fruit (Capsicum annuum). In Handbook of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 165–191.

- Maldonado-Bonilla, L.D.; Betancourt-Jiménez, M.; Lozoya-Gloria, E. Local and Systemic Gene Expression of Sesquiterpene Phytoalexin Biosynthetic Enzymes in Plant Leaves. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 121, 439–449.

- Lim, J.H.; Park, C.J.; Huh, S.U.; Choi, L.M.; Lee, G.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Paek, K.H. Capsicum annuum WRKYb Transcription Factor That Binds to the CaPR-10 Promoter Functions as a Positive Regulator in Innate Immunity upon TMV Infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 411, 613–619.

- Hutasingh, N.; Chuntakaruk, H.; Tubtimrattana, A.; Ketngamkum, Y.; Pewlong, P.; Phaonakrop, N.; Roytrakul, S.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Paemanee, A.; Tansrisawad, N.; et al. Metabolite profiling and identification of novel umami compounds in the chaya leaves of two species using multiplatform metabolomics. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134564.

- Ramos-Gomez, M.; Figueroa-Pérez, M.G.; Guzman-Maldonado, H.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Mendoza, S.; Quezada-Tristán, T.; Reynoso-Camacho, R. Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant Properties and Hypoglycemic Effect of Chaya (Cnidoscolus chayamansa) in STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12281.

- Rodrigues, L.G.G.; Mazzutti, S.; Siddique, I.; da Silva, M.; Vitali, L.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Subcritical Water Extraction and Microwave-Assisted Extraction Applied for the Recovery of Bioactive Components from Chaya (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius Mill.). J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 165, 104976.

- Quintal Martínez, J.P.; Segura Campos, M.R. Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (Mill.) I.M. Johnst.: A Food Proposal Against Thromboembolic Diseases. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 39, 1377–1410.

- Sánchez-Recillas, A.; Rivero-Medina, L.; Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Araujo-León, J.A.; Flores-Guido, J.S. Airway Smooth Muscle Relaxant Activity of Cordia dodecandra A. DC. Mainly by CAMP Increase and Calcium Channel Blockade. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 229, 280–287.

- Jiménez-Morales, K.; Castañeda-Pérez, E.; Herrera-Pool, E.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; García-Cruz, U.; Pech-Cohuo, S.C.; Pacheco, N. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Different Maturity Stages and Fruit Parts of Cordia dodecandra A. DC.: Quantification and Identification by UPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2127.

- Pacheco, N.; Méndez-Campos, G.K.; Herrera-Pool, I.E.; Alvarado-López, C.J.; Ramos-Díaz, A.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Talcott, S.U.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C. Physicochemical Composition, Phytochemical Analysis and Biological Activity of Ciricote (Cordia dodecandra A. D.C.) Fruit from Yucatán. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 440–444.

- Mannino, G.; Serio, G.; Bertea, C.M.; Chiarelli, R.; Lauria, A.; Gentile, C. Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant Properties of the Edible and Non-Edible Portions of Black Sapote (Diospyros Digyna Jacq.). Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132137.

- Yahia, E.M.; Gutierrez-Orozco, F.; de Leon, C.A. Phytochemical and Antioxidant Characterization of the Fruit of Black Sapote (Diospyros Digyna Jacq.). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2210–2216.

- Coeugniet, E.G.; Elek, E. Immunomodulation with Viscum Album and Echinacea purpurea Extracts. Onkologie 1987, 10, 27–33.

- Lim, T.K. Echinacea purpurea. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 340–371.

- Manayi, A.; Vazirian, M.; Saeidnia, S. Echinacea purpurea: Pharmacology, Phytochemistry and Analysis Methods. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2015, 9, 63–72.

- Classen, B.; Thude, S.; Blaschek, W.; Wack, M.; Bodinet, C. Immunomodulatory Effects of Arabinogalactan-Proteins from Baptisia and Echinacea. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 688–694.

- Mazza, G.; Cottrell, T. Volatile Components of Roots, Stems, Leaves, and Flowers of Echinacea Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3081–3085.

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, H.; Tai, G. Components of Heat-Treated Helianthus annuus L. Pectin Inhibit Tumor Growth and Promote Immunity in a Mouse CT26 Tumor Model. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 48, 190–199.

- Guo, S.; Ge, Y.; Na Jom, K. A Review of Phytochemistry, Metabolite Changes, and Medicinal Uses of the Common Sunflower Seed and Sprouts (Helianthus annuus L.). Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 95.

- Lokumana, C.R. Collection and Analysis of Volatiles of Various Cultivated Sunflower, Helianthus annuus, (Asteraceae) Germplasm and Investigation of Some Aspects of Host Selection in Adult Red Sunflower Seed Weevil, Smicronyx fulvus L., (Coleoptera Curculionidae); North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 2017.

- Gómez, C.C.E.; Ordaz, C.P.; San Martín, E.M.; Pérez, N.H.; Pérez, G.I.; Gómez, M.d.C.G. Cytotoxic Effect and Apoptotic Activity of Parmentiera Edulis DC. Hexane Extract on the Breast Cancer Cell Line MDA-MB-231. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 15–22.

- Perez, R.M.; Perez, C.; Zavala, M.A.; Perez, S.; Hernandez, H.; Lagunes, F. Hypoglycemic Effects of Lactucin-8-O-Methylacrylate of Parmentiera Edulis Fruit. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 71, 391–394.

- Do, T.V.T.; Suhartini, W.; Phan, C.U.; Zhang, Z.; Goksen, G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Nutritional Value, Phytochemistry, Health Benefits, and Potential Food Applications of Pouteria campechiana (Kunth) Baehni: A Comprehensive Review. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 103, 105481.

- Mena-Rejón, G.J.; Sansores-Peraza, P.; Brito-Loeza, W.F.; Quijano, L. Chemical Constituents of Pithecellobium Albicans. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 395–397.

- Vargas-Madriz, Á.F.; Kuri-García, A.; Vargas-Madriz, H.; Chávez-Servín, J.L.; Ferriz-Martínez, R.A.; Hernández-Sandoval, L.G.; Guzmán-Maldonado, S.H. Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb) Benth: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 4316–4336.

- De Almeida, C.L.F.; Brito, S.A.; De Santana, T.I.; Costa, H.B.A.; De Carvalho Júnior, C.H.R.; Da Silva, M.V.; De Almeida, L.L.; Rolim, L.A.; Dos Santos, V.L.; Wanderley, A.G.; et al. Spondias purpurea L. (Anacardiaceae): Antioxidant and Antiulcer Activities of the Leaf Hexane Extract. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6593073.

- Marisco, G.; Regineide, X.; Brendel, M.; Pungartnik, C. Antifungal Potential of Terpenes from Spondias purpurea L. Leaf Extract against Moniliophthora Perniciosa That Causes Witches Broom Disease of Theobroma Cacao. Int. J. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 7, 00215.

- Chen, C. Sinapic Acid and Its Derivatives as Medicine in Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases and Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3571614.

- Espíndola, K.M.M.; Ferreira, R.G.; Narvaez, L.E.M.; Silva Rosario, A.C.R.; da Silva, A.H.M.; Silva, A.G.B.; Vieira, A.P.O.; Monteiro, M.C. Chemical and Pharmacological Aspects of Caffeic Acid and Its Activity in Hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 541.

- Luo, Y.; Shang, P.; Li, D. Luteolin: A Flavonoid That Has Multiple Cardio-Protective Effects and Its Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 692.

- Taheri, Y.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Antika, G.; Yılmaz, Y.B.; Tumer, T.B.; Abuhamdah, S.; Chandra, S.; Saklani, S.; Kılıç, C.S.; Sestito, S.; et al. Paving Luteolin Therapeutic Potentialities and Agro-Food-Pharma Applications: Emphasis on In Vivo Pharmacological Effects and Bioavailability Traits. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1987588.